2.2 Types of Research Strategies

In their quest to understand the mind and behavior of humans and other animals, psychologists employ a variety of research strategies. Pfungst’s strategy was to observe Clever Hans’s behavior in controlled experiments. But not all research studies done by psychologists are experiments. A useful way to categorize the various research strategies used by psychologists is to think of them as varying along the following three dimensions (Hendricks et al., 1990):

- The research design, of which there are three basic types—experiments, correlational studies, and descriptive studies.

- The setting in which the study is conducted, of which there are two basic types—field and laboratory.

- The data-collection method, of which there are two basic types—self-report and observation.

Each of these dimensions can vary independently from the others, resulting in any possible combination of design, setting, and data-collection methods. Here we first describe the three types of research designs and then, more briefly, the other two dimensions.

Research Designs

The first dimension of a research strategy is the research design, which can be an experiment, a correlational study, or a descriptive study. Researchers design a study to test a hypothesis, choosing the design that best fits the conditions the researchers want to control.

34

Experiments

An experiment is the most direct and conclusive approach to testing a hypothesis about a cause-effect relationship between two variables. A variable is simply anything that can vary. It might be a condition of the environment, such as temperature or amount of noise, or it might be a measure of behavior, such as a score on a test. In describing an experiment, the variable that is hypothesized to cause some effect on another variable is called the independent variable, and the variable that is hypothesized to be affected is called the dependent variable. The aim of any experiment is to learn whether and how the dependent variable is affected by (depends on) the independent variable. In psychology, dependent variables are usually measures of behavior, and independent variables are factors that are hypothesized to influence those measures.

4

How can an experiment demonstrate the existence of a cause-effect relation between two variables?

More specifically, an experiment can be defined as a procedure in which a researcher systematically manipulates (varies) one or more independent variables and looks for changes in one or more dependent variables while keeping all other variables constant. If all other variables are kept constant and only the independent variable is changed, then the experimenter can reasonably conclude that any change observed in the dependent variable is caused by the change in the independent variable.

The people or animals that are studied in any research study are referred to as the subjects of the study. (Many psychologists today prefer to call them participants rather than subjects because “subject” is felt to have undesirable connotations of subordination and passivity [Kimmel, 2007], but the American Psychological Association [2010] approves both terms, and in general we prefer the more traditional and precise term subjects) In some experiments, called within-subject experiments (or sometimes repeated-measures experiments) each subject is tested in each of the different conditions of the independent variable (that is, the subject is repeatedly tested). In other experiments, called between-groups experiments (or sometimes, between-subjects experiments), there is a separate group of subjects for each different condition of the independent variable.

5

What were the independent and dependent variables in Pfungst’s experiment with Clever Hans?

Example of a Within-Subject Experiment In most within-subject experiments, a number of subjects are tested in each condition of the independent variable, but within-subject experiments can also be conducted with just one subject. In Pfungst’s experiments with Clever Hans, there was just one subject, Hans. In each experiment, Pfungst tested Hans repeatedly, under varying conditions of the independent variable.

In one experiment, to determine whether or not visual cues were critical to Hans’s ability to respond correctly to questions, Pfungst tested the horse sometimes with blinders and sometimes without. In that experiment the independent variable was the presence or absence of blinders, and the dependent variable was the percentage of questions the horse answered correctly. The experiment could be described as a study of the effect of blinders (independent variable) on Hans’s percentage of correct responses to questions (dependent variable). Pfungst took care to keep other variables, such as the difficulty of the questions and the setting in which the questions were asked, constant across the two test conditions. This experiment is a within-subject experiment because it applied the different conditions of the independent variable (blinders) to the same subject (Hans).

6

What were the independent and dependent variables in DiMascio’s experiment on treatments for depression? Why were the subjects randomly assigned to the different treatments rather than allowed to choose their own treatment?

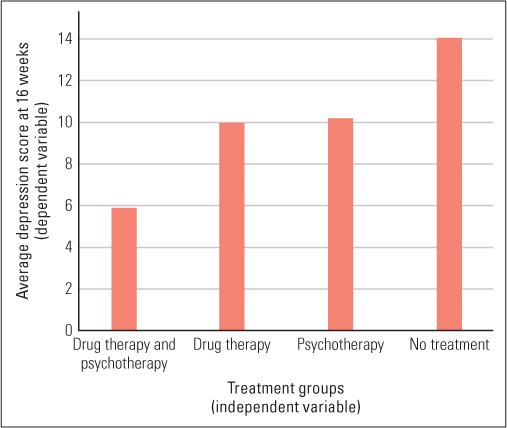

Example of a Between-Groups Experiment To illustrate a between-groups experiment, we’ll use a classic experiment in clinical psychology conducted by Alberto DiMascio and his colleagues (1979). These researchers identified a group of patients suffering from major depression (defined in Chapter 16) and assigned them, by a deliberately random procedure, to different treatments. One group received both drug therapy and psychotherapy, a second received drug therapy alone, a third received psychotherapy alone, and a fourth received no scheduled treatment. The drug therapy consisted of daily doses of an antidepressant drug, and the psychotherapy consisted of weekly talk sessions with a psychiatrist that focused on the person’s social relationships. After 16 weeks of treatment, the researchers rated each patient’s degree of depression using a standard set of questions about mood and behavior. In this experiment, the independent variable was the kind of treatment given, and the dependent variable was the degree of depression after 16 weeks of treatment. This is a between-groups experiment because the manipulations of the independent variable (that is, the different treatments used) were applied to different groups of subjects.

35

Notice that the researchers used a random method (a method relying only on chance) to assign the subjects to the treatment groups. Random assignment is regularly used in between-group experiments to ensure that the subjects are not assigned in a way that could bias the results. If DiMascio and his colleagues had allowed the subjects to choose their own treatment group, those who were most likely to improve even without treatment—maybe because they were more motivated to improve—might have disproportionately chosen one treatment condition over the others. In that case we would have no way to know whether the greater improvement of one group compared with the others derived from the treatment or from pre-existing differences in the subjects. With random assignment, any differences among the groups that do not stem from the differing treatments must be the result of chance, and, as you will see later, researchers have statistical tools for taking chance into account in analyzing their data.

The results of this experiment are shown in Figure 2.1. Following a common convention in graphing experimental results, which is used throughout this book, the figure depicts variation in the independent variable along the horizontal axis (known as the x-axis) and variation in the dependent variable along the vertical axis (the y-axis). As you can see in the figure, those in the drug-plus-psychotherapy group were the least depressed after the 16-week period, and those in the notreatment group were the most depressed. The results support the hypothesis that both drug therapy and psychotherapy help relieve depression and that the two treatments together have a greater effect than either alone.

Correlational Studies

Often in psychology we cannot conduct experiments to answer the questions because we cannot—for practical or ethical reasons—assign subjects to particular experimental conditions and control their experiences. Suppose, for example, that you are interested in the relationship between the disciplinary styles of parents and the psychological development of children. Perhaps you entertain the idea that frequent punishment is harmful, that it promotes aggressiveness or other unwanted characteristics. To test that hypothesis with an experiment, you would have to manipulate the discipline variable and then measure some aspect of the children’s behavior. You might consider randomly assigning some families to a strict punishment condition and others to other conditions. The parents would then have to raise their children in the manners you prescribe. But you cannot control families that way; it’s not practical, not legal, and not ethical. So, instead, you conduct a correlational study.

7

What are the differences in procedure between a correlational study and an experiment? How do the types of conclusions that can be drawn differ between a correlational study and an experiment?

A correlational study can be defined as a study in which the researcher does not manipulate any variable, but observes or measures two or more already existing variables to find relationships between them. Correlational studies can identify relationships between variables, which allow us to make predictions about one variable based on knowledge of another; but such studies do not tell us in any direct way whether change in one variable is the cause of change in another.

Example of a Correlational Study A classic example of a correlational study is Diana Baumrind’s (1971) study of the relationship between parents’ disciplinary styles and children’s behavioral development. Instead of manipulating disciplinary styles, she observed and assessed differences in disciplinary styles that already existed between different sets of parents. Through questionnaires and home observations, Baumrind classified disciplinary styles into three categories: authoritarian (high exertion of parental power), authoritative (a kinder and more democratic style, but with the parents still clearly in charge), and permissive (parental laxity in the face of their children’s disruptive behaviors). She also rated the children on various aspects of behavior, such as cooperation and friendliness, through observations in their nursery schools. The main finding (discussed more fully in Chapter 12) was that children of authoritative parents scored better on the measures of behavior than did children of authoritarian or permissive parents.

36

8

How does an analysis of Baumrind’s classic study of parental disciplinary styles illustrate the difficulty of trying to infer cause and effect from a correlation?

Why Cause and Effect Cannot Be Determined from a Correlational Study

It is tempting to treat Baumrind’s study as though it were an experiment and interpret the results in cause-effect terms. More specifically, it is tempting to think of the parents’ disciplinary style as the independent variable and the children’s behavior as the dependent variable and to conclude that differences in the former caused the differences in the latter. Thus, if parents would simply raise their children using an authoritative parenting style, their children would be more cooperative, friendly, and so forth. But because the study was not an experiment, we cannot justifiably come to that conclusion. The researcher did not control either variable, so we cannot be sure what was cause and what was effect. Maybe the differences in the parents’ styles did cause the differences in the children’s behavior, but other interpretations are possible. Here are some of these possibilities:

- Differences in children’s behavior may cause differences in parents’ disciplinary style, rather than the other way around. Some children may be better behaved than others for reasons quite separate from parental style, and parents with well-behaved children may simply glide into an authoritative mode of parenting, while parents with more difficult children fall into one of the other two approaches as a way of coping.

- The causal relationship may go in both directions, with parents and children influencing each other’s behavior. For example, children’s disruptive behavior may promote authoritarian parenting, which may promote even more disruptive behavior.

- A third variable, not measured in Baumrind’s study, may influence both parental style and children’s behavior in such a way as to cause the observed correlation. For example, anything that makes families feel good about themselves (such as having good neighbors, good health, and an adequate income) might promote an authoritative style in parents and, quite independently, also lead children to behave well. Or maybe the causal variable has to do with the fact that children are genetically similar to their parents and therefore have similar personalities: The same genes that predispose parents to behave in a kind but firm manner may predispose children to behave well, and the same genes that predispose parents to be either highly punitive or neglectful may predispose children to misbehave.

If you understand and remain aware of this limitation of correlational studies, you will not only be a stronger psychology student, but a much smarter consumer of media reports about research results. All too frequently, people—including even scientists who sometimes forget what they should know—use correlations to make unjustified claims of causal relationships on subjects including not only psychology, but health, economics, and more. The important take-home message is that “correlation does not imply causality.”

In some correlational studies, one causal hypothesis may be deemed more plausible than others. For example, we might be tempted to infer a cause-effect relationship between children’s violent behavior and the amount of time they spend watching violent television programs. However, that is a judgment based on logical thought about possible causal mechanisms or on evidence from other sources, not from the correlation itself (Rutter, 2007). As another example, if we found a correlation between brain damage to a certain part of the brain, due to accidents, and the onset of a certain type of mental disorder immediately following the accident, we would probably be correct in inferring that the brain damage caused the mental disorder. That possibility seems far more plausible than any other possible explanation of the relationship between the two variables.

37

In Baumrind’s study, one variable (parents’ disciplinary style) was used to place subjects into separate groups, and then the groups were compared to see how they differed in the other variable (the children’s behavior). Many correlational studies are analyzed in that way, and these studies are the ones most likely to be confused with experiments. In many other correlational studies, however, both variables are measured numerically and neither is used to assign subjects to groups. For example, a researcher might be interested in the correlation between the height of tenth-grade boys (measured in centimeters or inches) and their popularity (measured by counting the number of classmates who list the boy as a friend). In such cases, the data are assessed by a statistic called the correlation coefficient, which will be discussed in the section on statistical methods later in this chapter.

Descriptive Studies

9

How do descriptive studies differ in method and purpose from experiments and from correlational studies?

Sometimes the aim of research is to describe the behavior of an individual or set of individuals without assessing relationships between different variables. A study of this sort is called a descriptive study. Descriptive studies may or may not make use of numbers. As an example of one involving numbers, researchers might survey the members of a given community to determine the percentage who suffer from various mental disorders. This is a descriptive study if its aim is simply to describe the prevalence of each disorder without correlating the disorders to other characteristics of the community’s members. As an example of a descriptive study not involving numbers, an animal behaviorist might observe the courtship behaviors of mallard ducks to describe in detail the sequence of movements that are involved.

Some descriptive studies are narrow in focus, concentrating on one specific aspect of behavior, and others are broad, aiming to learn as much as possible about the habits of a particular group of people or species of animal. One of the most extensive and heroic descriptive bodies of research ever conducted is Jane Goodall’s work on wild chimpanzees in Africa. She observed the apes’ behavior over a period of 30 years and provided a wealth of information about every aspect of their lives (Goodall, 1986, 1988).

38

Research Settings

The second dimension of research strategy is the research setting, which can be either the laboratory or the field. A laboratory study is any research study in which the subjects are brought to a specially designated area that has been set up to facilitate the researcher’s collection of data or control over environmental conditions. Laboratory studies can be conducted in any location where a researcher has control over what experiences the subject has at that time. This is often in specially constructed rooms at universities, but in educational and child development research, for example, the “laboratory” may be a small room in a school or child care center.

In contrast to laboratory studies, a field study is any research study conducted in a setting in which the researcher does not have control over the experiences that a subject has. Field studies in psychology may be conducted in people’s homes, at their workplaces, at shopping malls, or in any place that is part of the subjects’ natural environment.

10

What are the relative advantages and disadvantages of laboratory studies and field studies?

Laboratory and field settings offer opposite sets of advantages and disadvantages. The laboratory allows the researcher to collect data under more uniform, controlled conditions than are possible in the field. However, the strangeness or artificiality of the laboratory may induce behaviors that obscure those the researcher wants to study. A laboratory study of parent-child interactions, for example, may produce results that reflect not so much the subjects’ normal ways of interacting as their reactions to a strange environment and their awareness that they are being observed. To counteract such problems, some researchers combine laboratory and field studies. It often happens that the same conclusions emerge from tightly controlled laboratory studies and less controlled, but more natural, field studies. In such cases, researchers can be reasonably confident that the conclusions are meaningful (Anderson et al., 1999).

In terms of how research settings relate to the three kinds of research designs discussed earlier, experiments are most often conducted in the laboratory because greater control of variables is possible in that setting, and correlational and descriptive studies are more often conducted in the field. But these relationships between research design and setting are by no means inevitable. Experiments are sometimes performed in the field, and correlational and descriptive studies are sometimes carried out in the laboratory.

As an example of a field experiment, psychologist Robert Cialdini (2003) wondered about the effectiveness of signs in public places, such as national parks, depicting undesired behaviors that visitors are asked to avoid. Do such signs reduce the behaviors they are designed to reduce? As a test, on different days Cialdini varied the signs placed along trails in Petrified Forest National Park intended to discourage visitors from picking up and taking pieces of petrified wood. He then measured, by observation, the amount of theft of petrified wood that occurred. For an example of a sign and the results Cialdini found, see Figure 2.2.

Data-Collection Methods

11

How do self-report methods, naturalistic observations, and tests differ from one another? What are some advantages and disadvantages of each?

The third dimension of research is the data-collection method, of which there are two broad categories: self-report methods and observational methods. Self-report methods are procedures in which people are asked to rate or describe their own behavior or mental state in some way. For example, in a study of generosity subjects might be asked to respond to questions pertaining to their own degree of generosity. This might be done through a written questionnaire, in which people check off items on a printed list that apply to them, indicate the degree to which certain statements are true or not true of them, or write answers to brief essay questions about themselves. Or it might be done through an interview, in which people describe themselves orally in a dialogue with the interviewer. An interview may be tightly structured, with the interviewer asking questions according to a completely planned sequence, or it may be more loosely structured, with the interviewer following up on some of the subjects’ responses with additional questions. In some cases, people are asked to make assessments of other people, such as parents or teachers asked to evaluate children in terms of aggression of agree-ableness, or individuals asked to evaluate their romantic partners’ tendencies toward jealousy.

39

One form of self-report is introspection, the personal observations of one’s thoughts, perceptions, and feelings. This was a method used by the founders of modern psychology, especially Wilhelm Wundt. Although Wundt used exacting controls in his introspection experiments, permitting them to be replicated in other laboratories, it is impossible to confirm another person’s thoughts, feelings, or perceptions. The highly subjective nature of introspection made it a target of criticism for early psychologists who believed that the science of psychology should be based on observable behavior, not on what people say they “feel.” Nonetheless, such sensory, cognitive, and emotional states are of great importance to the individual experiencing them and are very much “real.” Modern methods for measuring neural activity (discussed in Chapter 5 and elsewhere in this book) are able to correlate people’s introspections with what’s happening in the brain, providing more objective, “observable behavior” than was available to the pioneers of psychology.

Observational methods include all procedures by which researchers observe and record the behavior of interest rather than relying on subjects’ self-reports. In one subcategory, tests, the researcher deliberately presents problems, tasks, or situations to which the subject responds. For example, to test generosity a researcher might allow subjects to win a certain amount of money in a game and then allow them to donate whatever amount they wish to other subjects or to some cause. In the other subcategory, naturalistic observation, the researcher avoids interfering with the subjects’ behavior. For example, a researcher studying generosity might unobtrusively watch people passing by a charity booth outside of a grocery store to see who gives and who doesn’t. Consider a naturalistic research study conducted by Laura Berk (1986). Berk observed first- and third-grade children during daily math periods and related their behavior (particularly the incidence of talking to themselves) to their school performance. She reported that the older children were more likely to talk to themselves while they solved problems than were the younger children. The older children often quietly engaged in inaudible mutters and movements of their lips, apparently using language to guide their problem solving (for example, “Six plus six is twelve, carry the one…“). But those younger children who did talk to themselves while doing math problems tended to be the brighter children, apparently realizing before their peers that there was something they could do to make their job easier. These and other findings would have been difficult to assess in a laboratory situation.

One important caution about naturalistic observation research is called for here. Although it is sometimes possible to observe subjects unobtrusively, such as documenting how many people put money in a Salvation Army collection pot outside a grocery store, at other times, such as in the Berk study, subjects know they are being watched. Might the knowledge that someone is watching you affect how you behave? We know that it can. Thus, an obstacle to naturalistic observation is that the researchers may inadvertently, by their mere presence, influence the behavior they are observing. In a classic study performed in the 1930s at the Hawthorne Plant of Western Electric in Cicero, Illinois (Roethlisberger & Dickson, 1939), researchers investigated various techniques to improve workers’ productivity. These ranged from pay incentives, to different lighting conditions, to different work schedules. In all cases, the employees knew they were being observed. To the researchers’ surprise, most manipulations they tried resulted in enhanced performance, at least initially. This result, however, was not due to the specific factor being changed (better lighting, for example), but simply to the subjects’ knowledge that they were being watched and their belief that they were receiving special treatment. This has come to be known as the Hawthorne effect, and it is something that every researcher doing observational work needs to be aware of.

40

One technique for minimizing the Hawthorne effect takes advantage of the phenomenon of habituation, a decline in response when a stimulus is repeatedly or continuously present. Thus, over time, subjects may habituate to the presence of the researcher and go about their daily activities more naturally than they would if suddenly placed under observation.

None of these data-collection methods is in any absolute sense superior to another. Each has its purposes, advantages, and limitations. Questionnaires and interviews can provide information that researchers would not be able to obtain by watching subjects directly. However, the validity of such data is limited by the subjects’ ability to observe and remember their own behaviors or moods and by their willingness to report those observations frankly, without distorting them to look good or to please the researcher. Naturalistic observations allow researchers to learn firsthand about their subjects’ natural behaviors, but the practicality of such methods is limited by the great amount of time they take, the difficulty of observing ongoing behavior without interfering with it, and the difficulty of coding results in a form that can be used for statistical analysis. Tests are convenient and easily scored but are by nature artificial, and their relevance to everyday behavior is not always clear. What is the relationship between a person’s charitable giving in a laboratory test and that person’s charitable giving in real life? Or between a score on an IQ test and the ability to solve real-life problems? These are the kinds of questions that psychologists must address whenever they wish to use test results to draw conclusions about behaviors outside of the testing situation.

41

SECTION REVIEW

Research strategies used by psychologists vary in their design, setting, and data-collection method.

Research Designs

- In an experiment (such as the experiment on treatments for depression), the researcher can test hypotheses about causation by manipulating the independent variable(s) and looking for corresponding differences in the dependent variable(s) while keeping all other variables constant.

- In a correlational study, a researcher measures two or more variables to see if there are systematic relationships among them. Such studies do not tell us about causation.

- Descriptive studies are designed only to characterize and record what is observed, not to test hypotheses about relationships among variables.

Research Settings

- Laboratory settings allow researchers the greatest control over variables, but they may interfere with the behavior being studied by virtue of being unfamiliar or artificial.

- Field studies, done in “real-life” settings, have the opposite advantages and disadvantages, offering less control but perhaps more natural behavior.

Data-Collection Methods

- Self-report methods require the people being studied to rate or describe themselves, usually in questionnaires or interviews.

- Observational methods require the researcher to observe and record the subjects’ behavior through naturalistic observation or some form of test.

- Each data-collection method has advantages and disadvantages.