10.2 The Roots of Prejudice: Three Basic Causes

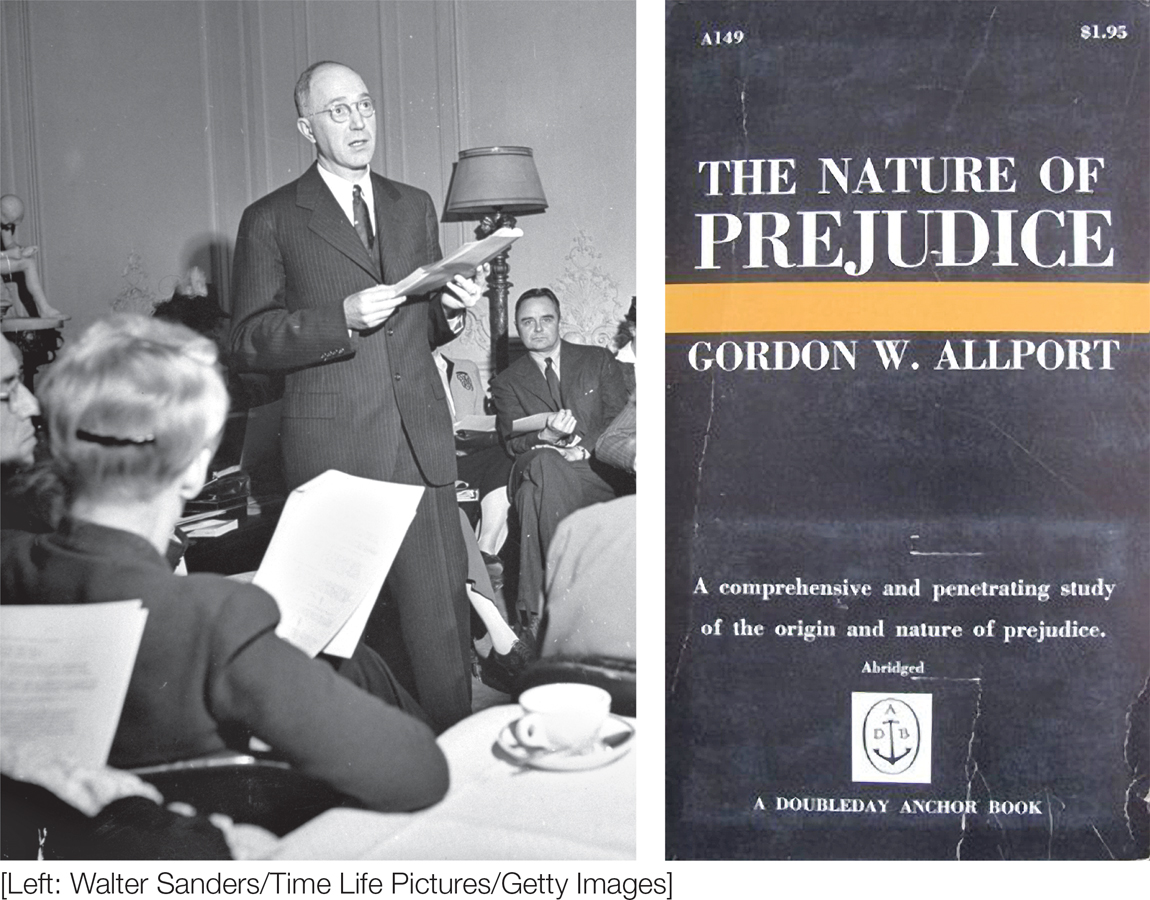

Given all the harm that has come from prejudice, stereotypes, and discrimination, why are these phenomena so prevalent? This is one of the central questions that Gordon Allport addressed in his classic book The Nature of Prejudice (1954). In a chapter titled “The Normality of Prejudgment,” Allport proposed three basic causes of prejudice, each of which is an unfortunate consequence of some very basic aspects of human thought and feeling.

353

Hostile Feelings Linked to a Category

Allport viewed the first fundamental cause of prejudice to be a result of two basic human tendencies:

First, people are likely to feel hostility when they are frustrated or threatened, or when they witness things they view as unpleasant or unjust.

Gordon Allport’s book The Nature of Prejudice launched more than six decades of research on the subject.

Second, as we noted in our chapters on social cognition, people tend to form schemas or categories and then view new stimuli as members of these categories. Just as we routinely categorize objects (see chapter 3), we also categorize other people as members of social groups, such as women, Asians, and teenagers, often within milliseconds of encountering them (Fiske, 1998). For example, when someone looks at pictures of others of a different race, the brain emits electrical signals (referred to as event-

Prejudice results from the combination of these two basic tendencies: the experience of hostile feelings linked to a salient category of people. For example, in Marseilles, a Frenchman robbed at gunpoint by another a Frenchman will likely experience fear and anger, hate that man, and hope he is caught and imprisoned. A Frenchman who is robbed by an Algerian man will experience the same emotions but is more likely to direct that hate toward Algerians, a prominent immigrant group in France, and may therefore want all Algerians expelled from his country. Because what is salient to the victimized individual in the latter example is the category Algerian, his negative feelings are overgeneralized to the category rather than being applied only to the individual mugger whose actions caused his negative experience.

Allport argues that we naturally tend to jump from single experiences with a member of an outgroup to overly broad generalizations about all members of that category. The typical midwestern American who has never met a Muslim and reads about Muslims only when an act of Islamic terrorism occurs is likely to link her negative feelings about terrorism to the category Muslims. An Afghan woman whose niece was killed by an American guided missile is likely to hate Americans. A suburban European American child who knows African Americans only through television shows portraying them primarily as criminals may view the entire group as violent and dangerous. A European American kid hassled by a Mexican American in a middle-

354

This idea of negative feelings generalized to an entire group can help explain many historical instances of increases in prejudice. A couple of very dramatic American examples concern Japanese Americans and Arab Americans. After the attack by the Japanese military on American forces at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Japanese Americans were commonly harassed. Many were removed from their homes and placed in internment camps. Similarly, after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, Americans exhibited more negative attitudes and behavior toward Arab and Muslim Americans. Although these reactions were predictable, they are classic examples of prejudice—

Realistic group conflict theory (Levine & Campbell, 1972) adds to Allport’s idea by arguing that the initial negative feelings between groups are often based on a real conflict or competition over scarce resources. If individuals in one group think that their access to land, water, jobs, or other resources is being threatened or blocked by another group, the resulting sense of threat and frustration is likely to generate negative emotions about the perceived rival group. This helps explain why when new groups of immigrants arrive in a country, hostility is usually part of the dominant group’s reaction, especially when economic times are tough and jobs are scarce (e.g., Dollard, 1938). Furthermore, these negative feelings are often culturally transmitted from generation to generation, so that intergroup hostilities are perpetuated even if the initial realistic conflict has become ancient history and is no longer pertinent.

Realistic group conflict theory

asserts that the initial negative feelings between groups are often based on a real conflict or competition regarding scarce resources.

Intergroup anxiety theory (Stephan & Stephan, 1985) extends realistic group conflict theory by arguing that historical conflict between different groups makes members of both groups anxious in their encounters with each other. As a result, these feelings of intergroup anxiety can be triggered even when individuals merely think about the outgroup. This anxiety can result from fear of rejection, domination, exploitation, or violence; guilt over past treatment of the group; or uncertainty about how to behave toward members of the group. This anxiety fuels prejudice because these negative feelings become associated with outgroup members.

Intergroup anxiety theory

Theory proposing that intergroup prejudice leads individuals to experience anxiety when they think of or interact with members of an outgroup.

Ingroup Bias: We Like Us Better Than Them

The second cause of prejudice that Allport identified results from a basic tendency to prefer what is familiar and what is connected to oneself to what is unfamiliar and not connected to oneself. As the mere exposure effect discussed in chapter 8 shows, the more familiar we are with a stimulus, the more we like it. We like—

Taking an evolutionary perspective, some psychologists have argued that a preference for familiar others is probably something adaptive that has been selected for (e.g., Park et al., 2003). Our ancestors, living in small groups, were probably safer if they stayed close to their own. If they ventured away from their own group and encountered other groups, they may have experienced peril, including exposure to germs. One finding consistent with this possibility is that when thoughts of disease are made salient, people become particularly negative toward ethnically different others (Faulkner et al., 2004). Allport noted that because of common backgrounds, experiences, and knowledge, it’s also just easier to know what to say and how to behave around those who are members of the ingroup.

In addition to this familiarity-

355

Social identity theory (see chapter 9) (Tajfel & Turner, 1986) actually looks at the relationship between self-

On which side would you crack the egg? Hundreds of years ago Jonathan Swift anticipated the finding that minimal differences can lead to ingroup bias. In Gulliver’s Travels he describes wars breaking out between those who believe eggs should be cracked at the big end and those who believe they should be cracked at the small end.

A large body of experimental research also supports the existence of ingroup bias and the validity of social identity theory. One important line of inquiry has examined whether arbitrarily formed groups immediately exhibit ingroup bias. For example, Jonathan Swift’s (1726/2001) classic satire Gulliver’s Travels describes wars breaking out between those who believe eggs should be cracked at the big end and those who believe they should be cracked at the small end. Empirical evidence of such arbitrary forms of prejudice was found in a seminal study by Henri Tajfel. In this study, British high school students viewed a series of dots on a screen and were asked to estimate how many there were (Tajfel et al., 1971). The researchers told one random set of students that they were “overestimators” and the other set that they were “underestimators.” Even in such minimal groups, researchers found bias in favor of distributing more resources to members of one’s own group than to the outgroup, whether or not these groups had a history of contact with one another (Tajfel & Turner, 1986).

Theory and research also suggest that in most cases the liking for the ingroup is stronger and more fundamental than the dislike of the outgroup (e.g., Allport, 1954; Brewer, 1979). Allport noted that in many contexts, people are very accepting of bias in favor of their own children and family, and pride in their own nation. However, this “love prejudice” often has negative consequences for outgroups. An African American woman who is having trouble finding employment would feel little comfort in knowing that it’s not so much that White employers are biased against African Americans but just that they prefer to hire their “own kind.” In addition, if we view an outgroup as threatening in some way to our beloved ingroup, our love for our own group may lead to hate for that outgroup.

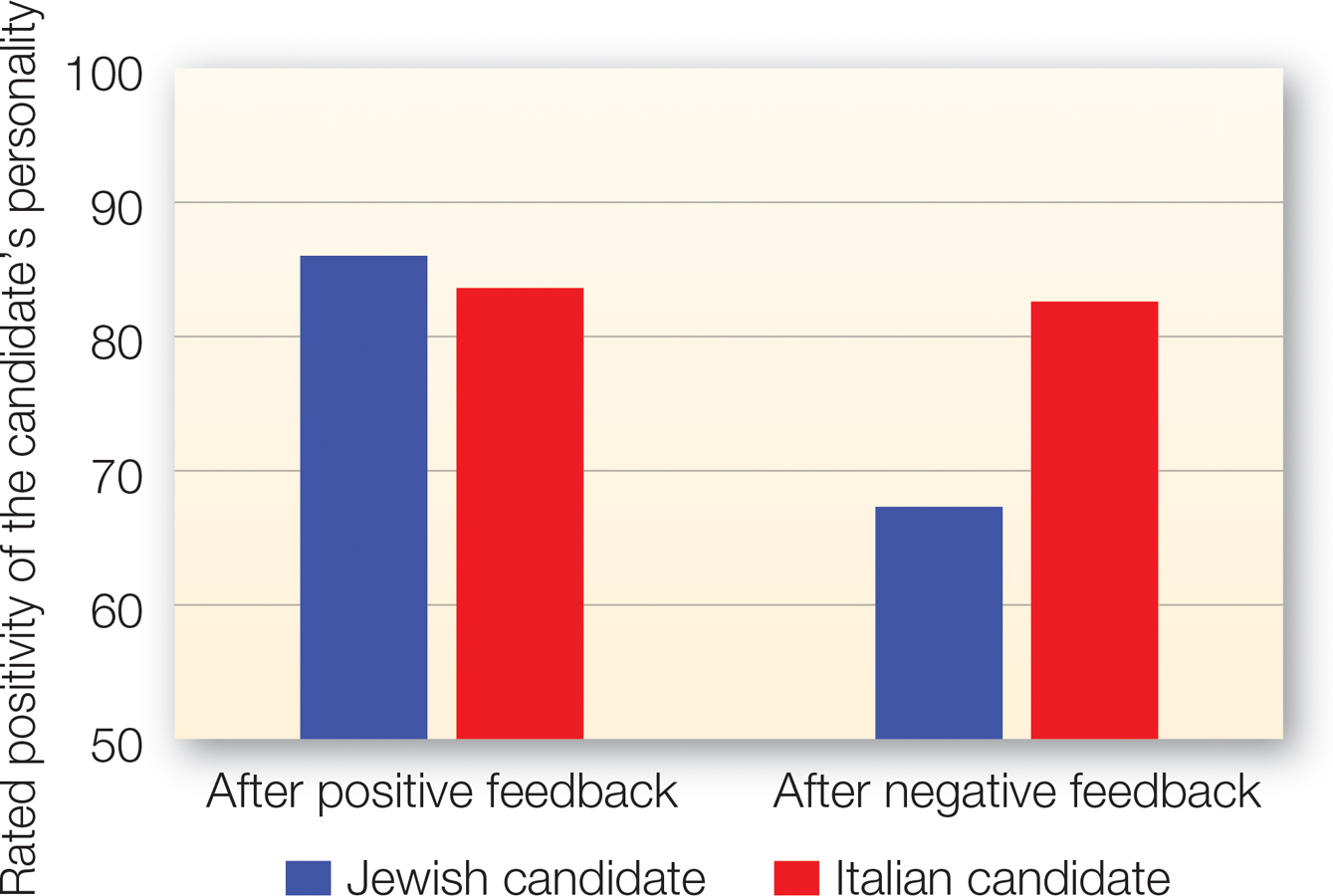

FIGURE 10.2

The Role of Self-

After receiving negative feedback, American participants derogated a woman they believed was Jewish American rather than Italian American.

[Data source: Fein & Spencer (1997)]

A second important line of research has tested the prediction from social identity theory that ingroup bias serves self-

356

Another example of this kind of self-

Ethnocentrism, the Cultural Worldview, and Threat

Allport’s third basic cause of prejudice stems from the fact that each of us is raised within a particular cultural worldview and therefore has specific ideas about what is right and wrong and good and bad. If the worldview that we internalize from childhood explicitly portrays particular groups negatively, we likely will to follow suit. So simply conforming to the norms and values of one’s worldview can lead to prejudice. Supporting this idea, researchers have found that in places where prejudice is normative, such as the Deep South of the United States in the 1950s, the more people conform in general, the more prejudiced they tend to be (e.g., Pettigrew, 1958).

Ethnocentrism

Viewing the world through our own cultural value system and thereby judging actions and people based on our own culture’s views of right and wrong and good and bad.

Think ABOUT

357

Ethnocentric biases lead people to judge others’ cultural preferences and beliefs not just as different but as inferior to their own.

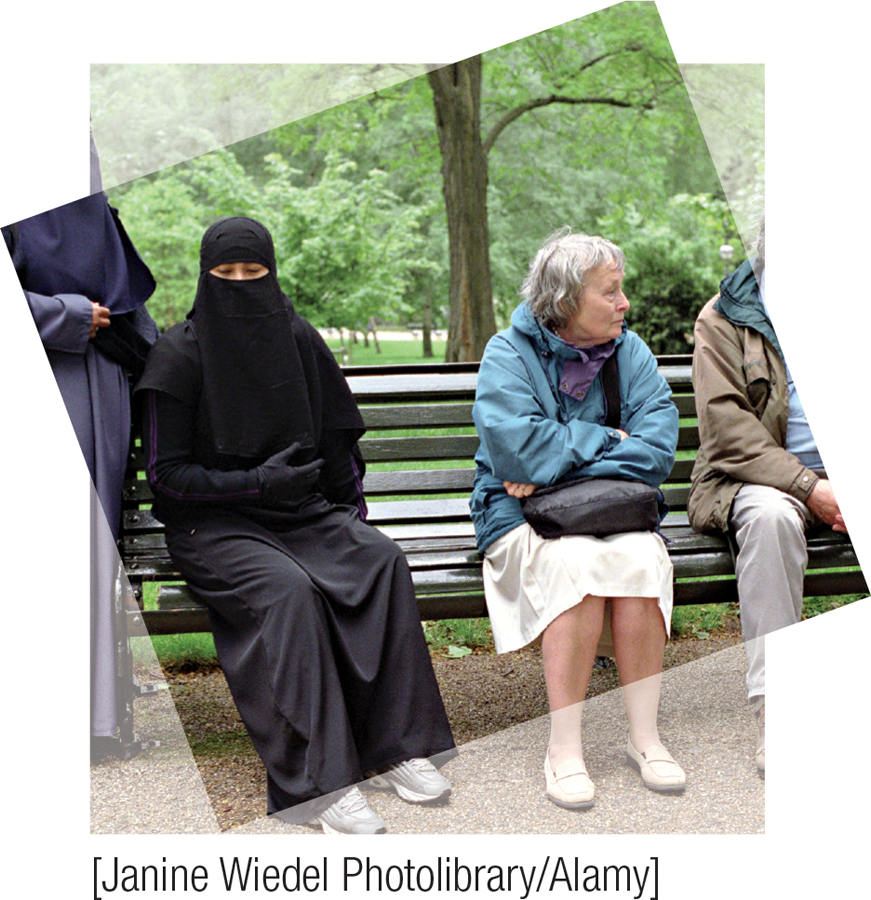

The internalized worldview contributes to prejudice in another important way. Because this worldview determines our view of what is right and good, we can’t help but judge others on the basis of those cultural values. This kind of judgment is called ethnocentrism (Sumner, 1906) and often leads us to hold negative attitudes about others who were raised in different cultures. An American who finds out that people in culture Z believe in bathing only twice a year is going to have a hard time not judging the members of that culture negatively: “They’re dirty and primitive!” By the same token, members of culture Z may observe the American tendency to bathe or shower virtually every day as bizarre: “They’re wasteful and compulsive!” These kinds of judgments get more serious when Americans learn of cultures that practice female circumcision or believe that women should never leave the house without covering every part of their bodies. When are right and wrong matters of mere cultural preference? When are they a legitimate basis for judging members of another group negatively? It is very hard to say, because our sense of right and wrong is so intertwined with the cultural worldview in which we were raised.

Symbolic Racism

The theory of symbolic racism (Sears & Kinder, 1971) posits that the tendency to reject those groups that don’t conform to one’s own view of the world underlies much of the racial prejudice that European Americans have against African Americans. From this perspective, many European Americans have internalized traditional, conservative Eurocentric moral values. From their perspective, African Americans are a threat to these values and to what they consider as the American way of life.

Symbolic racism

A tendency to express negative biases held about a racial outgroup not at the group directly, but at social policies seen as benefiting that group.

People who exhibit signs of symbolic racism don’t think they are prejudiced against Blacks or other minority groups. Rather, their negative attitudes toward these groups are expressed symbolically as opposition to policies that are seen as giving advantages to minority groups. They might deny that minorities continue to face discrimination and believe that racial disparities result from the unwillingness of people in minority groups to work hard enough. Although they recognize that disliking a group of people is indefensible, those who are high in symbolic racism feel perfectly justified in opposing social programs aimed at rectifying social inequalities that African Americans experience.

The theory of symbolic racism has been particularly useful in showing how prejudice is symbolically represented in diverging political opinions (Sears & Henry, 2005). In a typical study, participants complete questionnaires that measure symbolic racism (for example, indicating how much they agree with the statement that Blacks no longer face much discrimination). Those who score high on measures of symbolic racism—

Terror Management Theory

We’ve seen that people tend to think poorly of those who seem to live by a different set of rules and beliefs. But why can’t people just leave it at “Different strokes for different folks”? According to the existential perspective of terror management theory, one reason is that people must sustain faith in the validity of their own cultural world-

The novelist James Baldwin summed it up this way:

Life is tragic simply because the earth turns and the sun inexorably rises and sets, and one day, for each of us, the sun will go down for the last, last time. Perhaps the whole root of our trouble, the human trouble, is that we will sacrifice all the beauty of our lives, will imprison ourselves in totems, taboos, crosses, blood sacrifices, steeples, mosques, races, armies, flags, nations, in order to deny the fact of death, which is the only fact we have (1963, p. 105)

Basing their work on this idea, terror management researchers have tested the hypothesis that raising the problem of mortality would make people especially positive toward others who support their worldview and especially negative to others who implicitly or explicitly challenge it. In the first study testing this notion, when reminded of their own mortality, American Christian students became more positive toward a fellow Christian student and more negative toward a Jewish student (Greenberg et al., 1990). Similarly, when reminded of death, Italians and Germans became more biased toward their own cultures and against other cultures (Castano et al., 2002; Jonas et al., 2005). Reminders of mortality also increase prejudice against the physically disabled because they remind us of our own physical vulnerabilities (Hirschberger et al., 2005).

In a pair of studies particularly pertinent to the ongoing tensions in the Middle East, researchers found that when reminded of their own mortality, Iranian college students expressed greater support for suicidal martyrdom against Americans (Pyszczynski et al., 2006). The second study showed that politically conservative American college students who were reminded of their mortality similarly supported preemptively bombing countries that might threaten the United States, regardless of “collateral damage” (Pyszczynski et al., 2006). And in yet another troubling study, Hayes and colleagues (2008) found that Christian Canadians who were reminded of their mortality were better able to avoid thoughts of their own death if they imagined Muslims dying in a plane crash.

358

|

The Roots of Prejudice: Three Basic Causes |

|

Gordon Allport proposed three basic causes of prejudice, each based on fundamental ways that people think and feel. |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Hostility plus categorization We tend to feel hostility when we are frustrated or threatened. When negative feelings are associated with a member of an outgroup, we tend to overgeneralize those negative feelings and associated beliefs to the entire group. |

Ingroup bias We prefer what is familiar, including people like us. A portion of our self- When our self- |

Threats to one’s world view Our ethnocentrism leads us to judge people from different cultures more negatively. Ethnocentric biases are more severe when we feel vulnerable or if we see another’s worldview as threatening to our own. |