Chapter Introduction

| CHAPTER | 3 |

3 The Core Elements of Social Cognition

80

81

TOPIC OVERVIEW

The “How” of Social Cognition: Two Ways to Think About the Social World

The Strange Case of Facilitated Communication

Dual Process Theories

The Smart Unconscious

Application: Can the Unconscious Help Us Make Better Health Decisions?

The “What” of Social Cognition: Schemas as the Cognitive Building Blocks of Knowledge

Where Do Schemas Come From? Cultural Sources of Knowledge

How Do Schemas Work? Accessibility and Priming of Schemas

Confirmation Bias: How Schemas Alter Perceptions and Shape Reality

Beyond Schemas: Metaphor’s Influence on Social Thought

SOCIAL PSYCH OUT IN THE WORLD A Scary Implication: The Tyranny of Negative Labels Application: Moral Judgments and Cleanliness Metaphors

Returning to the “Why”: Motivational Factors in Social Cognition and Behavior

Priming and Motivation

Motivated Social Cognition

SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY AT THE MOVIES Pi Mood and Social Judgment

The Next Step Toward Understanding Social Understanding

Think back to your first kiss. You probably remember who you were with and how you felt. But do you remember the day of the week or what you were wearing? Most people would like to think that their memories are like snapshots of the past (maybe with a little Instagram filtering to give them a warm glow), yet recollections of even distinctive events lack a lot of detail. Moreover, people often remember events in ways that differ from how they actually occurred.

Like memory, ordinary sensory perception captures only a thin slice of the objective world. For example, the human eye sees only a portion of the electromagnetic spectrum, whereas bees and other insects can detect ultraviolet light. Everyday perception is also riddled with inaccuracies, some persistent. As just one example, it seems perfectly obvious to see the sun as “rising” and “setting” as it traverses the sky, yet we know that the sun remains stationary while the earth revolves around it. Our window into reality is not only small, it’s dirty.

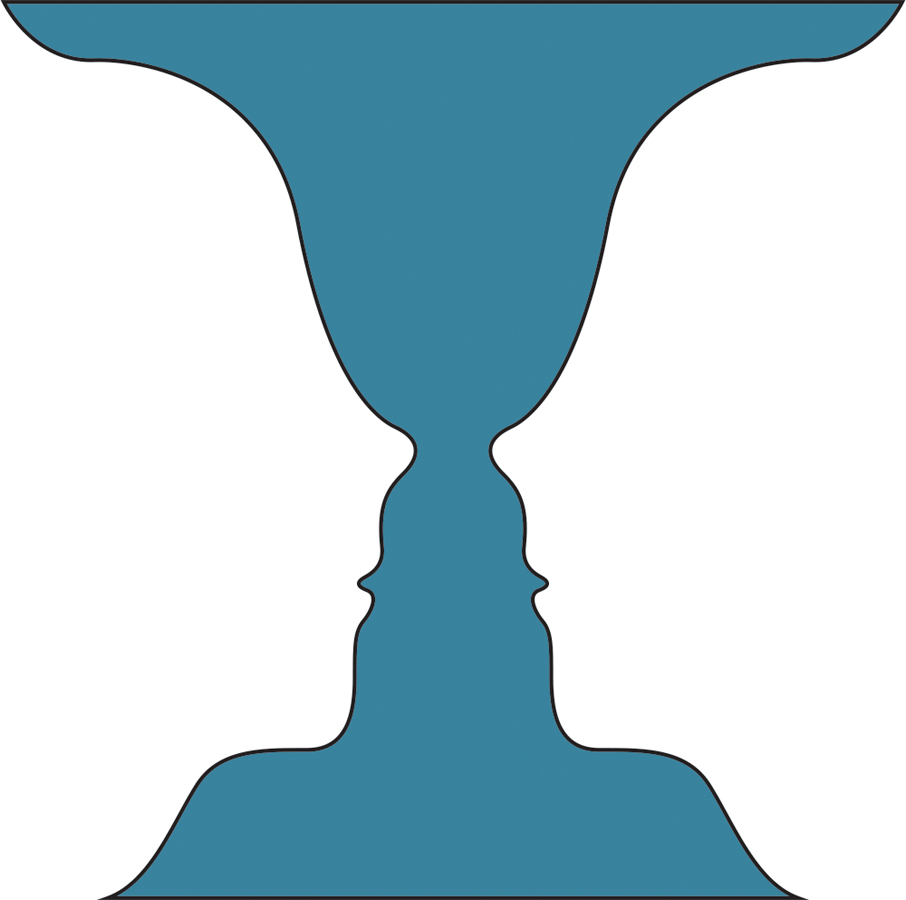

FIGURE 3.1

Figure and Ground

Do you see a vase or two faces? The mind plays an active part in how we construct reality.

Most of us normally take it for granted that our understanding of the world is a straightforward reflection of reality as it exists outside of us. We assume—

82

In the mid-

After thinking about that first kiss, you might see the image in FIGURE 3.1 as two faces looking at each other. Look again, and you’ll notice that the same image can be seen as a dark vase against a white background. When most people stare at this image, these two interpretations pop back and forth in their mind’s eye. The fact that the same physical stimulus can be viewed in more than one way shows that the perceiver has an active role in what is perceived. The whole is more than the sum of its parts.

The insights of the Gestalt school had a monumental influence on social psychology. If the mind constructs an understanding of even simple stimuli like the image in FIGURE 3.1, then certainly it must take an active role in shaping how a person makes sense of the people, ideas, and events that he or she encounters in everyday life. But how? What are the specific mental processes through which we construct a meaningful understanding of the social world? The research area known as social cognition emerged in the 1970s with the goal of answering this question. Its penetrating discoveries are at the heart of the social cognitive perspective and also the topic of this and the next chapter.