3.3 The “What” of Social Cognition: Schemas as the Cognitive Building Blocks of Knowledge

So far we’ve outlined the broad motives and systems that guide our thinking about the social world. Let’s turn now to consider some of the more specific thought processes that people use to understand the world. The first thing to notice is how quickly and effortlessly the mind classifies stimuli into categories. Categories are like mental containers into which people place things that are similar to each other. Or, more precisely, even if two things are quite different from one another (two unique individuals, for instance), when people place them in the same category (“frat boys”), they think about those two items as though they were the same. This makes life easier.

Categories

Mental “containers” in which people place things that are similar to each other.

Think ABOUT

To appreciate what categories can do, stop and look around your surroundings. What do you see? As for this author, I’m sitting at the dining room table in my house. I see my laptop in front of me and a stack of books nearby, along with my half-

Categorization is an interesting process in its own right, but it is just the starting point of our mind’s active meaning making. That’s because as soon as people classify a stimulus as an instance of a category, their minds quickly access knowledge about that category, including beliefs about the category’s attributes, expectations about what members of that category are like, and plans for how to interact with it, if at all. All of this knowledge is stored in memory in a mental structure called a schema. For example, if you are at the library and you categorize a person behind the desk as a librarian, you instantly access a schema for the category librarian that contains beliefs about which traits are generally shared by members of that group (e.g., intelligence), theories about how librarians’ traits relate to other aspects of the world (e.g., librarians probably do not enjoy extreme sports), and examples of other librarians you have known. Bringing to mind schemas allow the person to “go beyond the information given” (Bruner, 1957), elaborating on the information that strikes their senses with what they already know (or think they know). We can demonstrate this with a simple example. Read the following paragraph:

Schema

A mental structure, stored in memory, that is based on prior knowledge.

94

The procedure is quite simple. First, you arrange things into different groups. Of course, one pile may be sufficient, depending on how much there is to do. If you have to go somewhere else due to lack of facilities, that is the next step; otherwise you are pretty well set. It is important not to overdo things. That is, it is better to do too few things at once than too many. At first the whole procedure will seem complicated. Soon, however, it will become just another facet of life (Bransford & Johnson, 1973, p. 400).

You might be scratching your head right now, wondering what these instructions are referring to. If you close your textbook and five minutes later try to remember all of the points in the paragraph, you will probably run into difficulty. What if we tell you that the paragraph is about laundry? Now, reread the paragraph and you will see that the information makes much more sense to you than it did initially. After five minutes, you might do a reasonable job of remembering each of the steps described. The mere mention of the word laundry activated your schema of this process and made it a template for understanding the information you were reading.

Schemas are given special names depending on the type of knowledge that they represent. Schemas that represent knowledge about events are called scripts. These types of schemas (like the laundry example) always involve a temporal sequence, meaning that they describe how events unfold over time (first you sort, then you put one pile into the machine, then you add the soap, and so on). Scripts make coordinated action possible. Playing a game of tennis requires that both you and your partner have a schema of the game, so that you can coordinate your actions and follow the rules of the game, even though you are playing against one another. They also allow you to fill in missing information. If I told you that I got a sandwich at the student union, I don’t need to tell you, for example, that I paid for it. You can fill that detail in because you have the same basic “getting food at a restaurant” script as I do. Our reliance on scripts becomes embarrassingly apparent when we find ourselves without a script for a new situation. Imagine being invited to a Japanese tea ceremony but not knowing where to sit, what to say and when to say it, and how to sip the tea—

Scripts

Schemas about an event that specify the typical sequence of actions that take place.

Schemas that represent knowledge about other people are called impressions. Your schema of the cyclist Lance Armstrong might include physical characteristics (athletic, good looking), personality traits (charismatic, courageous), and other beliefs about him (philanthropist, cancer survivor, stripped of titles after doping scandal). Similarly, we can also have a schema for a category of people (e.g., sports superstars), called a stereotype. You can see that your impression of Armstrong contains many traits (e.g., wealthy, athletic, courageous) that are also part of your stereotype for sports superstars. Finally, as we will discuss in chapter 5, we also have a schema about ourselves—

Impressions

Schemas people have about other individuals.

Self-concept

A schema people have about themselves.

Your schema of Lance Armstrong might include aspects of his physical characteristics (athletic), personality traits (courageous), and beliefs about his life experiences (cancer survivor, stripped of Tour de France titles after doping scandal).

[Bryn Lennon/Getty Images]

95

Regardless of their type, the content of our schemas consists of a pattern of learned associations. These patterns of associations can change and expand over time. You first might have learned about Lance Armstrong as an incredible athlete and cancer survivor and only later had to update this positive view of him after repeatedly encountering media reports about his use of performance-

But it’s also important to realize that schemas are not passively filled up with information from the outside. Because of our need for specific closure—

Where Do Schemas Come From? Cultural Sources of Knowledge

Let’s take a closer look at where we acquire the knowledge that makes up our schemas. The example of Lance Armstrong pointed to various sources of knowledge. In some cases, we come into direct contact with people, events, and ideas and form concepts on the basis of that personal experience. But looking at this from the cultural perspective, we also learn a great deal about our social world indirectly, from parents, teachers, peers, books, newspapers, magazines, television, movies, and the Internet. A lot of our general knowledge comes during childhood from the culture in which we are raised. As children learn language and are told stories, they are taught concepts such as honesty and courage, good and evil, love and hate. From this learning, people develop ideas about what people in the world are like, the events that matter in life, and the meaning of their own thoughts and feelings, among other fundamental lessons.

A considerable amount of our cultural knowledge is transmitted to us by our parents, but also by peers, teachers, and mass media sources. For most children in industrialized nations, television and movies provide scripts of situations (workplace interactions: Mad Men; romance: the Twilight series), schemas of types of people (villain, hero, femme fatale, nerd, ingénue) and stereotypes of groups of people (gay men are effeminate; grandmothers are kind; Asians are martial artists) before the child has firsthand experience with such situations, people, and groups. And children intuitively sense that television and books provide a preview of the next steps in their lives: Grade school kids tend to like shows and books about middle school, and middle school kids tend to like shows and books about high school.

96

Finally, the basic way that we categorize information and build schemas is thought to be culturally universal, but as we have described it here, the content of those schemas and how they are organized is shaped by our cultural experiences. This can result in cultural differences in the meaning that concepts can sometimes have. For example, kids who grow up in a rural Native American culture—

Rumors and Gossip

Rumors and gossip are two other common sources of knowledge contained in our schemas. Much of what we learn about other people or events comes from news passed from one person to another. But beware. When information is passed from person to person to person before you get it, it tends to be distorted in various ways.

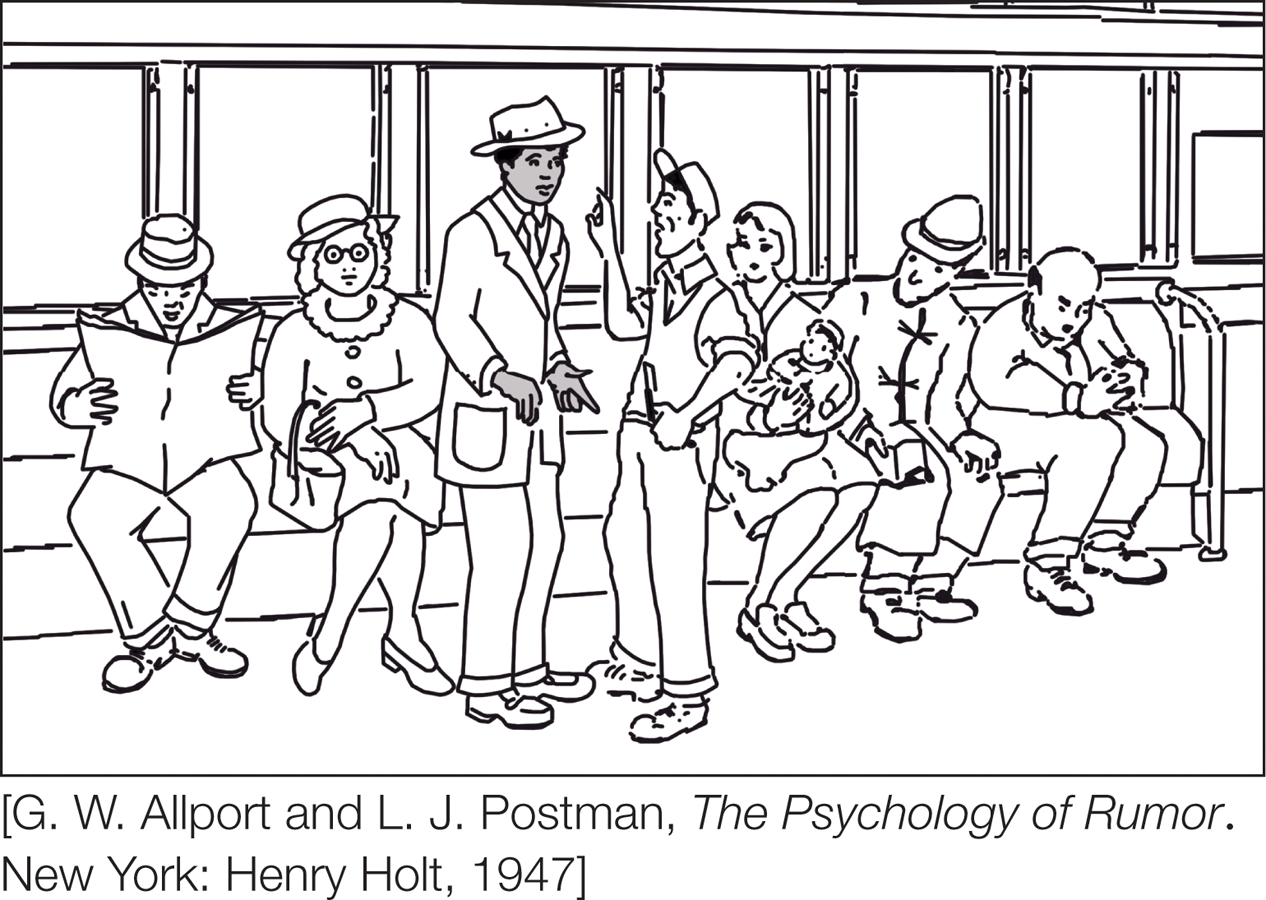

FIGURE 3.6

Spreading Rumors

People talked about the event depicted in this picture to others, who in turn told the story to still others, and so on. Over the course of several retellings, people’s memories of the event became more consistent with racial stereotypes: Eventually the man holding the razor was remembered as Black, not White.

[G. W. Allport and L. J. Postman, The Psychology of Rumor. New York: Henry Holt, 1947]

For one, as people perceive and relay information, it is altered a bit as it is filtered by each person’s schemas and motive for specific closure. Specifically, transmitted information can be biased by processes called sharpening and leveling. Think about how you tell a story to a friend. You’re probably going to emphasize the main features of the story, which is called sharpening, and leave out a lot of details, which is called leveling. The main features are more memorable than the details, and they also make for a more interesting tale. An unfortunate consequence of this bias is that people hearing about a person or event, rather than gaining knowledge firsthand, will tend to form an oversimplified, extreme impression of that person or event (Baron et al., 1997; Gilovich, 1987).

For example, Robert Baron and colleagues (1997) had a participant watch a videotape in which a young man described unintentionally getting drunk at a party, getting involved in a fight, and getting into a subsequent car accident. The man noted this was uncharacteristic of him, that he was egged on by friends, and that he regretted his actions. The participant rated the man on various positive and negative traits. Then the participant, now in the role of storyteller, was asked to speak into a tape recorder to describe the man’s story. Listeners then heard the audiotape and rated the man on the same traits. The listeners rated the man more negatively than the teller did. These effects seem to result both from a tendency of storytellers to leave out mitigating factors and complexities and a tendency of listeners to attend only to the central aspects of the stories they hear.

In addition to this tendency to tell simplified stories, our stereotypes of groups can also make us biased in our recall and retelling of information. Gordon Allport and Joseph Postman (1947) demonstrated this back in the 1940s in a study involving White American participants. They briefly showed a person a picture depicting a scene on the New York subway involving a White man standing, holding a razor, and pointing his finger at a Black man (FIGURE 3.6). They then had that person describe the scene to another person who had not seen the picture. That second person then described the scene to a third person, and so on, until the information had been conveyed to a seventh person. More than half the time, that seventh person reported that the scene involved the Black man, rather than the White man, holding the razor. So when we get our information filtered through lots of people, it’s pretty likely that prevalent schemas (such as stereotypes about a person’s group) have biased the information.

97

Mass Media Biases

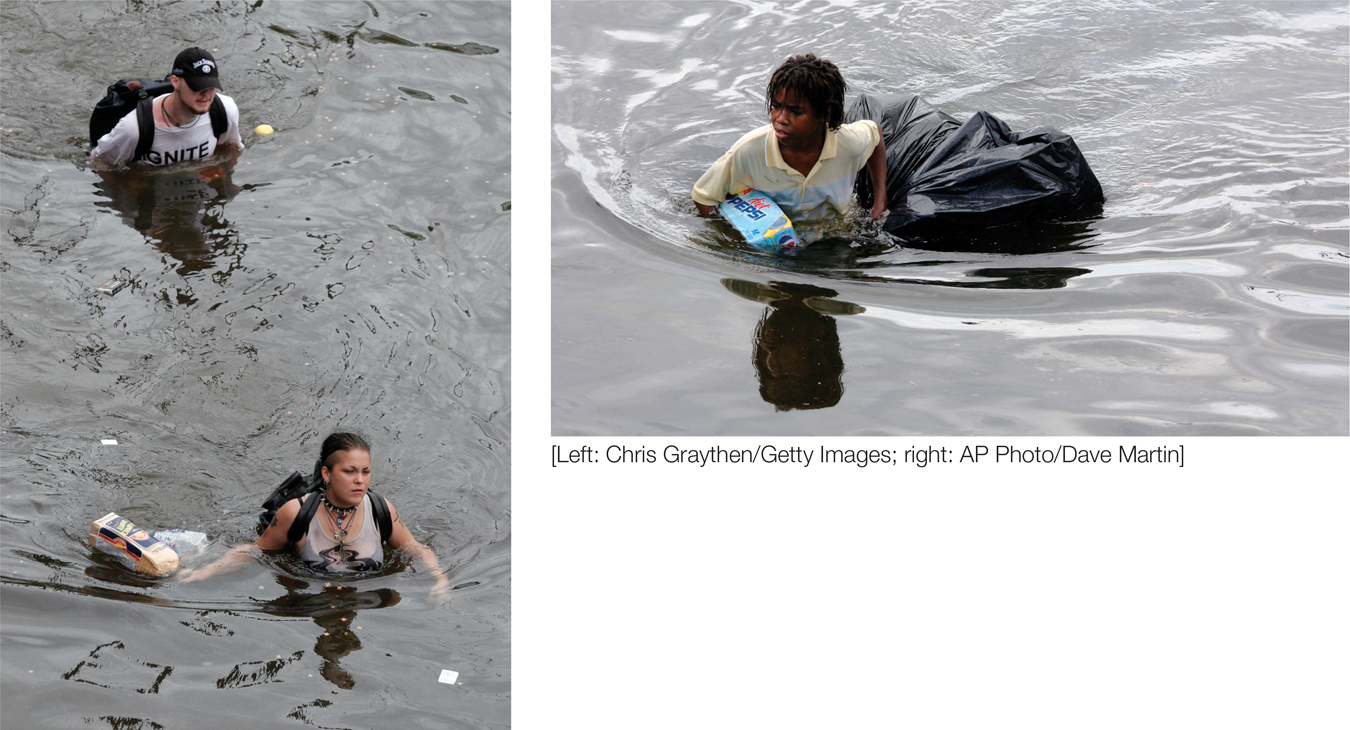

FIGURE 3.7

Media Biases

After Hurricane Katrina, both of these images appeared in different news sources. Whereas the media described the White people as finding food in grocery stores, they described this Black individual as having looted a grocery store.

[Left: Chris Graythen/Getty Images; right: AP Photo/Dave Martin]

Of course, we don’t get information only from having it told to us directly by others; we also learn a great deal from the stories we see and hear in the media. Just as rumors and gossip can distort the truth, media portrayals seldom are realistic accounts of what life is like, although they do provide vivid portrayals of possible scenarios. Think about your own schemas or scripts about dating and romantic love. Your earliest ideas about such matters probably came from fairy tales, television shows, the Internet, and movies. Unfortunately, these media offer biased views of many of these matters. For example, they tend to portray romantic relationships and love in oversimplified ways; to portray men, women, and ethnic groups in stereotypic ways; and to show a lot of violence (Dixon & Linz, 2000). The latter feature may explain why people who watch a lot of television think that crime and violence are far more prevalent in the world than they actually are (Shanahan & Morgan, 1999).

News programming is based on reality, and so people tend to assume it paints a fairly realistic, accurate, and less biased picture of events and people. But the news is created at least as much as it is reported. Those who produce the news choose which events and people to report about, and what perspective on the events to provide. These decisions are heavily influenced by concerns with television ratings and newspaper sales, and by the political and social preferences of those who own and sponsor the television programs, radio shows, newspapers, and magazines that report the news. And just as Allport and Postman showed over six decades ago, racial stereotypes can play a role as well. Just consider the two different descriptions of similar actions by people dealing with the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina’s devastation of New Orleans in 2005 (FIGURE 3.7). Both images show people leaving a grocery store and wading through floodwaters with food and supplies; the White people are described as “finding” food, whereas the Black individual is described as “looting.”

98

How Do Schemas Work? Accessibility and Priming of Schemas

We now have a sense of how important schemas are in helping us to acquire and organize information about the people, ideas, and events that we encounter. But which of the many schemas stored in a person’s memory will be activated and shape thought and action at any given moment?

The person’s current situation plays a major role in activating particular schemas. If the characteristics of a social gathering across the street—

Accessibility refers to the ease with which people can bring an idea into consciousness and use it in thinking. When a schema is highly accessible, the salience of that schema is increased: it is activated in the person’s mental system, even if she is not consciously aware of it, and it tends to color her perceptions and behavior (Higgins, 1996). We just saw that the characteristics of the person’s current situation can increase the salience of a schema, making it more accessible for thinking and acting.

Accessibility

The ease with which people can bring an idea into consciousness and use it in thinking.

Salience

The aspect of a schema that is active in one’s mind and, consciously or not, colors perceptions and behavior.

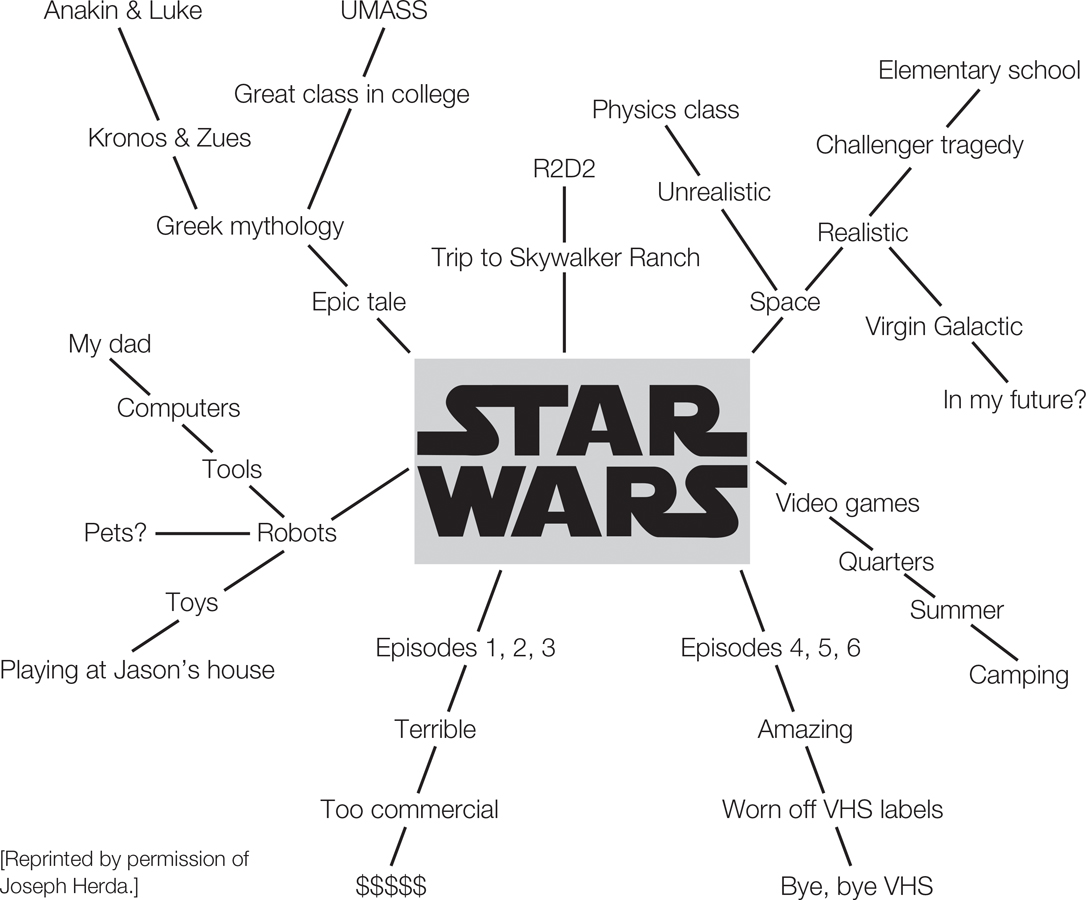

Priming occurs when something in the environment activates an idea that increases the salience of a schema. This happens because the information that we store in memory is connected in associative networks (FIGURE 3.8). These networks are tools that psychologists use to describe how pieces of information stored in a person’s memory are linked to other bits of information (Anderson, 1996; Collins & Loftus, 1975). These links result from semantic associations and experiential associations. Semantic associations result when two concepts are similar in meaning or belong to the same category. The words nice and kind, for example, have similar meanings; the words dog and cat both refer to household pets. Thus, we might expect them to be linked in a person’s associative network. Experiential associations occur when one concept has been experienced close in time or space to another concept. For example, for many people who consume their fair share of television or live in high-

Priming

The process by which exposure to a stimulus in the environment increases the salience of a schema.

Associative networks

Models for how pieces of information are linked together and stored in memory.

FIGURE 3.8

Associative Networks

Information is organized in associative networks in which closely related concepts are cognitively linked. Bringing one concept to mind can prime other concepts connected to it, sometimes without the person’s conscious awareness.

[Reprinted by permission of Joseph Herda.]

Semantic associations

Mental links between two concepts that are similar in meaning or that are parts of the same category.

Experiential associations

Mental links between two concepts that are experienced close together in time or space.

99

In addition to the immediate environment and priming, the person’s personality determines how accessible certain schemas are. Chronically accessible schemas are those that represent information that is important to an individual, relevant to how they think of themselves, or used frequently (Higgins, 2012; Markus, 1977). Such schemas are very easily brought to mind by even the most subtle reminder. For example, Mary is really interested in environmental issues, whereas Wanda is attuned to contemporary fashion. Mary is more likely to notice a hybrid car in the parking lot or express disdain over the plethora of plastic cups lying around at a party. Meanwhile, Wanda has her fashion radar working and her associated constructs chronically accessible, so she may dislike the tacky cups and be more likely than Mary to notice that Cynthia arrived in last season’s designer shoes. Even though they are in the same situation, the differences in what schemas are chronically accessible for Mary and Wanda lead to very different perceptions and judgments of the scene.

Chronically accessible schemas

Schemas that are easily brought to mind because they are personally important and used frequently.

People are also likely to interpret others’ behavior in terms of their own chronically accessible schemas (Higgins et al., 1982). If you read a biography of Herman Melville and if honesty is a chronically accessible trait for you, you would be likely to have a good memory for incidents in Melville’s life that pertain to honesty, and your overall impression of Melville will be largely colored by how honest he appears to have been. On the other hand, if kindness is chronically accessible for you, his incidents of kindness or unkindness would be particularly memorable and influence your attitudes.

Situational and chronic influences on schema accessibility also can work together to influence our perceptions of the world. For example, after witnessing a fellow student smile as a professor praises her class paper, students in one study were more likely to rate her as conceited if they had very recently been primed with words related to the schema arrogance, but this effect was most pronounced for students who showed high chronic accessibility for the schema conceitedness (Higgins & Brendl, 1995). In other words, a certain situation or stimulus may prime particular schemas for one person but not for another, depending on which ideas are chronically accessible to each (Bargh et al., 1986).

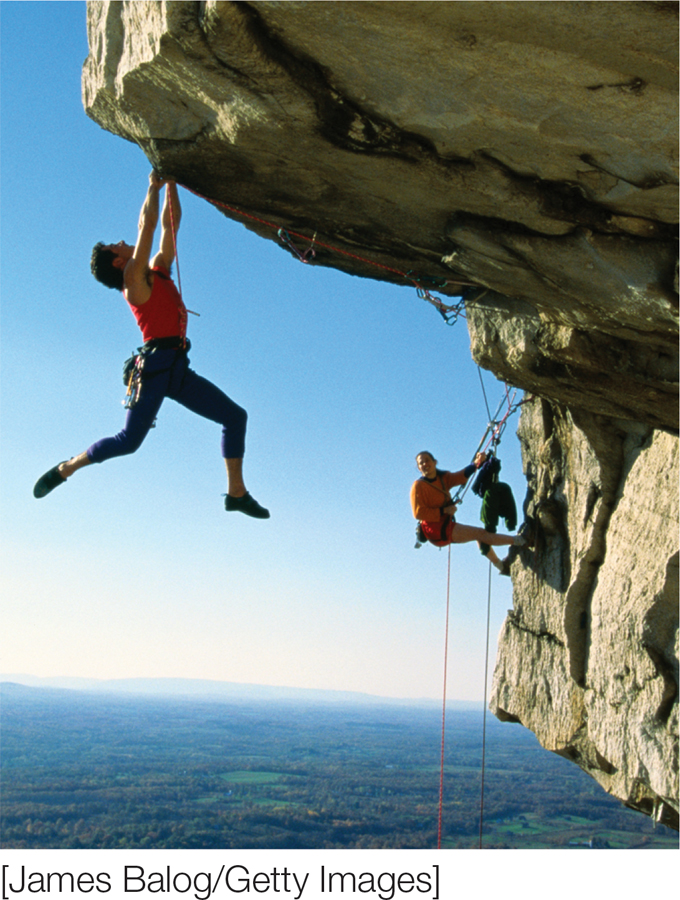

Priming and Social Perception

This man is free climbing without a safety harness. Would you describe him as adventurous or reckless? Because of priming, your impression might be influenced by what you were thinking about just before meeting him.

[James Balog/Getty Images]

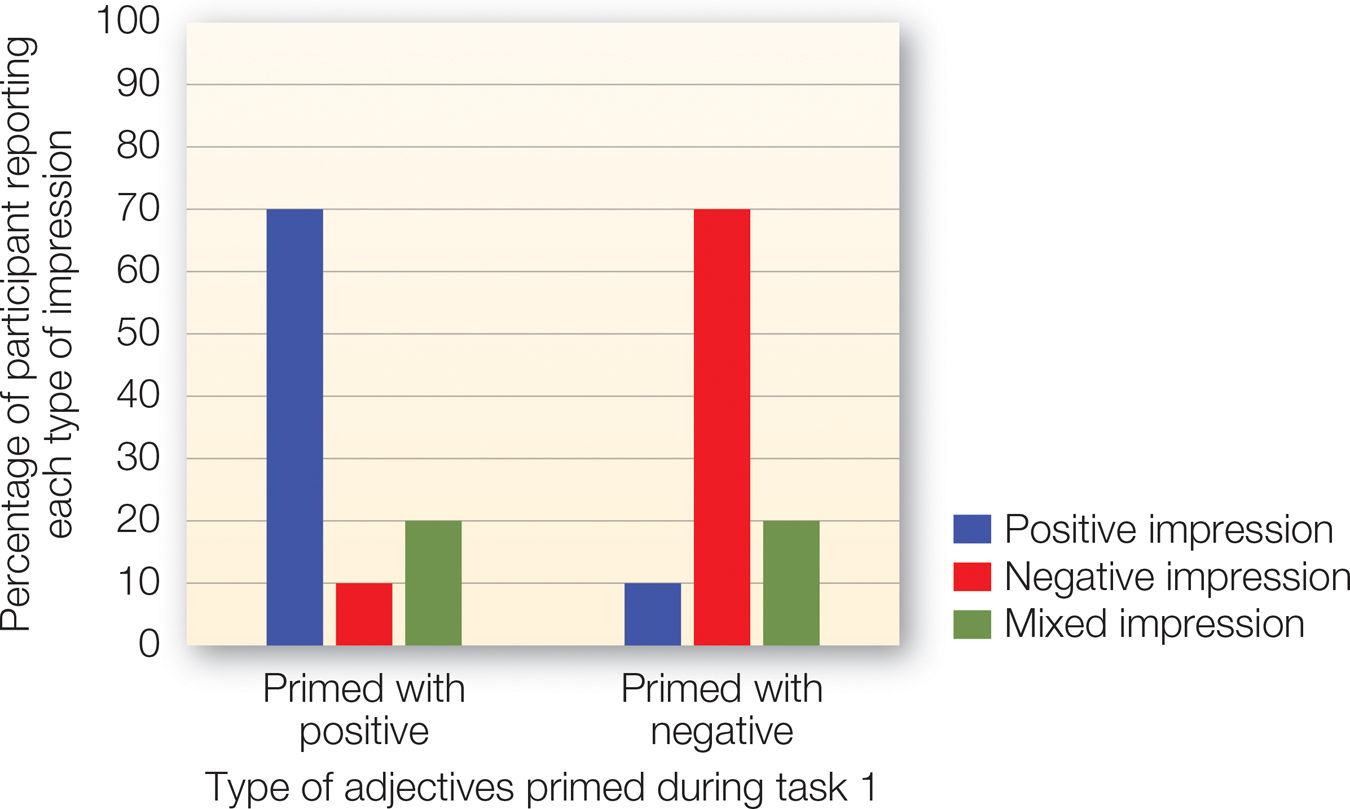

FIGURE 3.9

Forming Impressions

In this experiment, people’s impressions of a man named Donald were influenced by adjectives that had previously been primed. If they had just read several positive words, they formed a more positive impression than if they had just read several negative words.

[Data source: Higgins et al. (1977)]

Now that we have some understanding of how schemas operate, let’s examine in a bit more detail the consequences that schemas have for social perception and behavior. Imagine that you recently met a fellow named Donald. You learn that Donald is the type of person you might see in an energy-

100

A study by Higgins and colleagues (1977) suggests that your impression will depend on the traits that are accessible to you before you met him. Participants in this study were told they would be completing two unrelated studies on perception and reading comprehension, but in actuality the tasks were related. In the “first” study, participants performed a task in which they identified colors while reading words (commonly referred to as a Stroop task). In this task, you might see the word bold printed in blue letters, and your job would be to identify the color blue. This task gives the researchers a way to make certain ideas accessible for some participants but not for others. Half of the participants were randomly assigned to read words with negative implications (e.g., reckless). The other half of the participants read words with positive implications (e.g., adventurous). In the “second” study, participants were asked to read information about a person named Donald who takes part in various high-

Priming and Behavior

Just like impressions, social behavior can be influenced by recently primed schemas without the person being consciously aware of their influence. Consider this scenario. You show up to participate in a psychology study, thinking that it concerns language proficiency. You are asked to complete a task in which you try to unscramble words to make sentences. You’re told to use four of the five words presented. You start on the task and are presented with they/her/bother/see/usually. So you start scribbling something like “they usually bother her” and then proceed to the next set of words. Unknown to you, you have been randomly assigned to be in a condition in which words related to the schema rudeness have been primed (notice the word bother). Other participants were presented with neutral words or words related to the schema politeness (e.g., respect).

Think ABOUT

After completing a series of such sentences, you take your packet to the experimenter to find out what you need to do next. The problem is that the experimenter is stuck in conversation with another person, and the conversation doesn’t seem likely to end anytime soon. Think about a time when you are in a hurry but have to wait your turn. Would you wait patiently or try to interrupt others so that you can get on your way? Would other thoughts in your mind influence your behavior?

Study results suggest that they would (Bargh et al., 1996). When no category was primed, 38% of participants interrupted within a 10-

101

The Role of the Unconscious

Why are priming studies useful? They illustrate how our experiential system can operate behind the scenes, influencing our everyday thought and behavior outside of our awareness. Indeed, psychologists from Freud (1923/1961b) to Wilson (2002) have made the point that consciousness is the mere tip of an iceberg: We are continually influenced by features of the environment and mental processes without being aware of them.

Of course, this idea is not completely new in popular culture. Over the years there have been a number of controversial media accounts of subliminal priming. For example, in 1957, a movie theater proprietor claimed to have boosted popcorn and soda sales at concession stands by presenting subliminal messages encouraging patrons to visit the snack bar. This was later discovered to be false because no such messages were actually presented, but it certainly raised the ire of many moviegoers at the time. In 1990, the heavy metal band Judas Priest was sued over purportedly presenting subliminal messages in one of their songs that encouraged a young man to commit suicide.

Although these examples turned out to be groundless, subliminal priming is a reality. It’s just that now we understand how and when subliminal primes are likely to influence thought and behavior. Part of this development is owing to advances in technology, because we now have the means to present information (such as words and pictures) precisely long enough to activate them in the mind without bringing them into conscious attention. (In most experiments, exposures range from 10 to 100 milliseconds.)

We can see the effect of such subliminal priming in a study by Bargh and Pietromonaco (1982). They had participants read about a person named Donald (no relation to the earlier mountain climber) who refused to pay his rent until the landlord painted the apartment. Prior to reading about Donald, participants completed a computer task in which they were asked to identify where on the screen a brief flash appeared. Unknown to participants, directly following the flash a word was presented for 100 milliseconds to the periphery of their visual focus, followed by a string of “XXX”s that served to cover (or mask) the stimulus. Participants were shown 100 flashes. If participants were exposed to a lot of words related to hostility (curse, punch), they judged Donald to be more aggressive than did participants exposed to only a few or no hostility-

We now also have a much better theoretical grasp of how subliminal priming works, and therefore when it will—

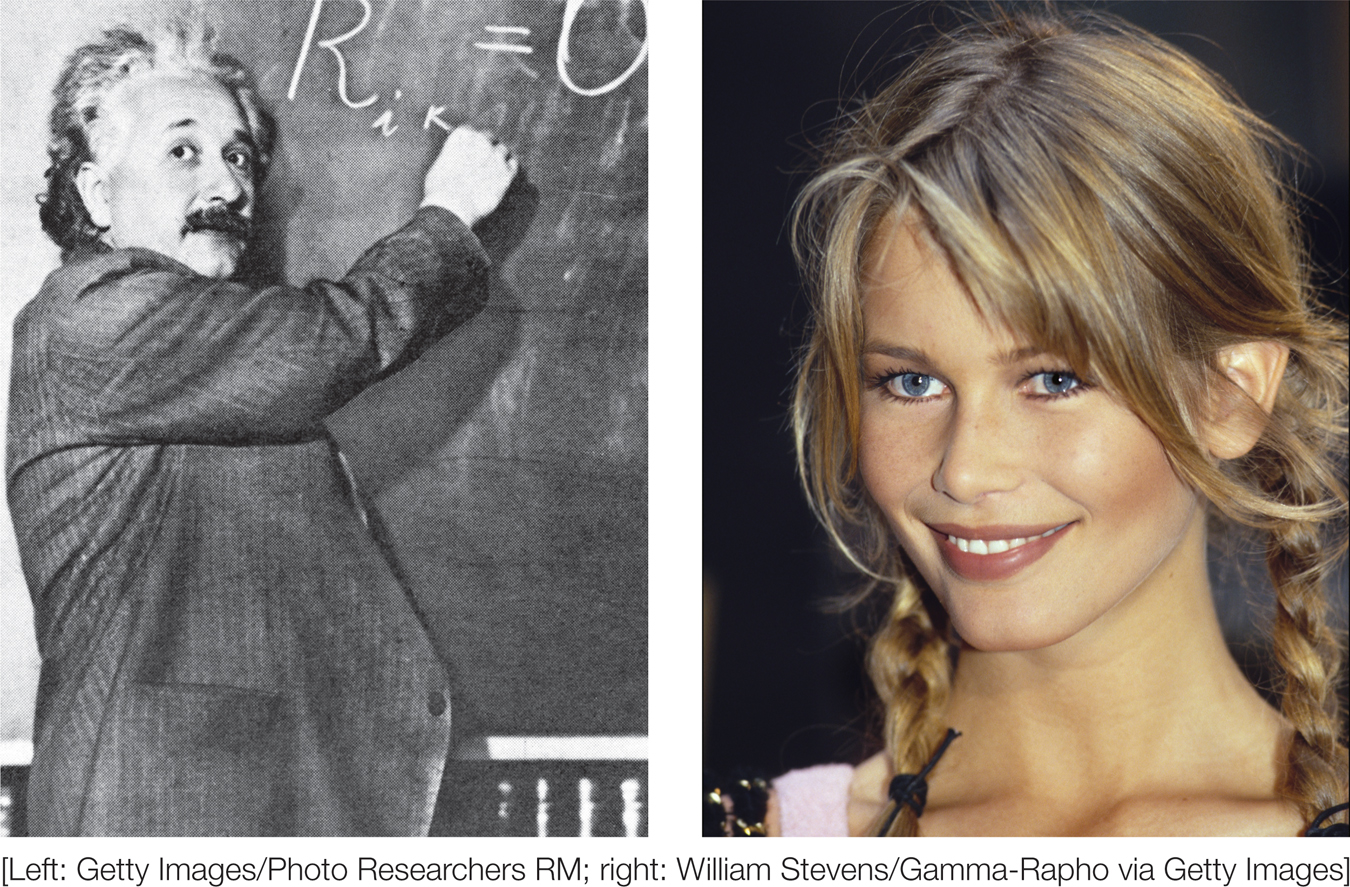

Assimilation and Contrast

The priming effects described so far are known as assimilation effects. This is because the judgment of the person or event is assimilated in, or changes in the direction of, the primed idea. For instance, priming the schema reckless increased the perception of mountain climbing Donald as reckless. But primes sometimes have the opposite consequence, leading to contrast effects. For example, in some studies, priming the schema hostility led people to view a person as less hostile (Lombardi et al., 1987; Martin, 1986). Although there are some complexities to determining when assimilation effects and when contrast effects are likely to occur (Higgins, 1996), contrast effects seem to emerge under a few conditions. The first is when people are very aware of the primed information and that it might affect their subsequent judgments. Accordingly, assimilation effects are consistently found for subliminal and subtle primes, but contrast effects are common when the primes and their relation to the subsequent judgment are very obvious. In these situations, people’s conscious cognitive system often tries to counteract the potential influence of the prime by shifting their judgment or behavior in the direction opposite of that implied by the prime (Wegener & Petty, 1995).

Assimilation effects

Occur when priming a schema (e.g., reckless) changes a person’s thinking in the direction of the primed idea (e.g., perceiving others as more reckless).

Contrast effects

Occur when priming a schema (e.g., reckless) changes a person’s thinking in the opposite direction of the primed idea (e.g., perceiving others as less reckless).

When primes create contrast effects: People can assimilate the concept intelligence and perform better when primed with the category professors rather than the category supermodels. Yet if primed with the specific person Albert Einstein, instead of the specific supermodel Claudia Schiffer, they tend to show a contrast effect and perform worse intellectually.

[Left: Getty Images/Photo Researchers RM; right: William Stevens/Gamma-

102

Two other conditions in which contrast can occur are when the prime is extreme or when it evokes a specific example of a category (Dijksterhuis et al., 1998; Herr, 1986; Schwarz & Bless, 1992). For example, when rating oneself after being primed with an extreme example, it may be harder to view oneself as consistent with the category. And when primed with a specific person who fits the category, the individual is more likely to compare the self with that specific person. In one study (Dijksterhuis et al., 1998), when students were asked to think about professors in general, they performed better on a test of general knowledge than students asked to think about supermodels in general (an assimilation effect). However, when participants were asked to think about specific exemplars of those categories (Albert Einstein as a professor and Claudia Schiffer as a supermodel), the specific exemplars caused participants to compare themselves with the exemplars, leading to a contrast effect in which those primed with Albert Einstein did worse than those primed with Claudia Schiffer. After all, it’s rather difficult to think of oneself as smart when compared with Einstein!

Confirmation Bias: How Schemas Alter Perceptions and Shape Reality

Schemas and the expectations and interpretations that they produce are generally quite useful. Your party schema tells you what to expect there, how to dress, and so forth. Your mom schema helps you predict and interpret things your mom will say and do. And the schemas that become active in particular situations are usually the ones most relevant to that situation. However, once we have a schema, we tend to view new information in such a way as to confirm what we already believe or feel. This is known as confirmation bias. In chapter 1 (pp. 13-

This effect happens for a number of reasons. First, once we have a schema of a person or situation, that schema guides us to look for certain kinds of information and ignore other kinds of information. We see this demonstrated in a study by Snyder and Frankel (1976). Participants watched a silent videotape of a woman being interviewed. They were told that the interview was about either sex or politics. Participants were told to watch the videotape to assess the woman’s emotional state. When participants thought the interview was about sex, they rated her as more anxious than when they thought the interview was about politics. The videotape was the same in both cases, but when participants thought the topic was sex, they expected the woman to be anxious over discussing such a personal topic, and therefore they watched more closely for nonverbal signs of anxiety. You’ve heard the expression “Seeing is believing”; studies such as these suggest that the converse holds true as well: “Believing is seeing”!

103

Second, a salient schema leads us to interpret ambiguous information in a schema-

The Ironic Biasing Influence of Objective Information

Could this insidious schema-

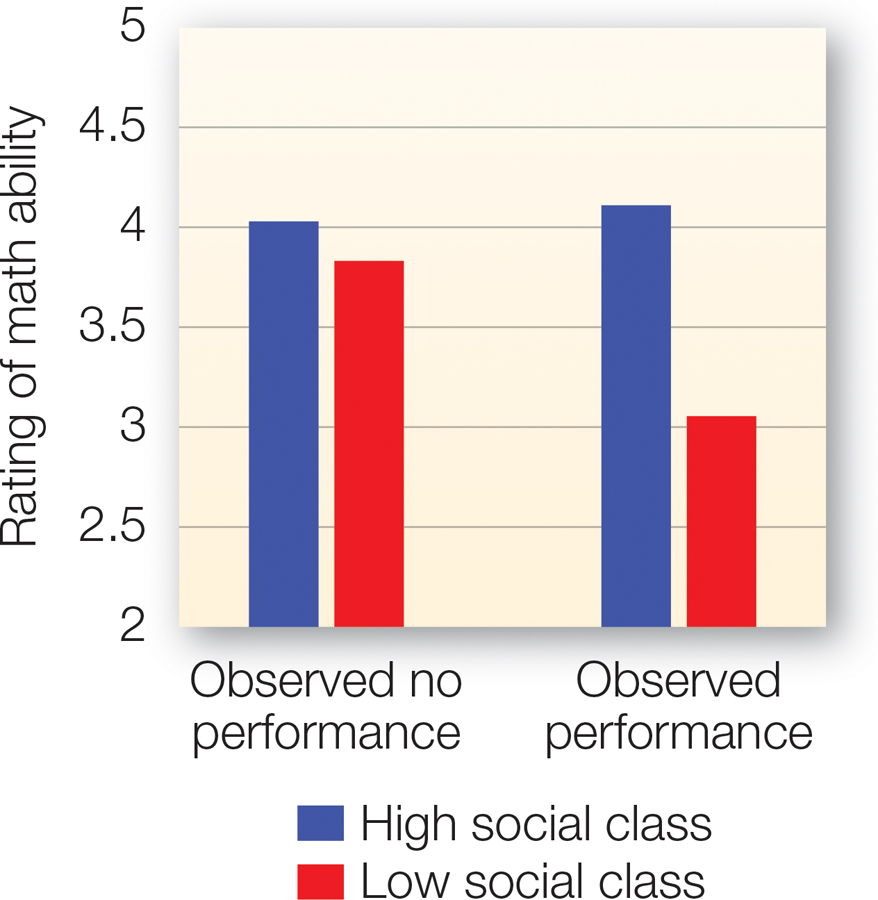

FIGURE 3.10

Schemas Bias Interpretation

When rating the math ability of a little girl, participants were not biased by her social class if they had no opportunity to observe her taking an achievement test. However, those who watched a video of her taking an oral test interpreted her performance more negatively if they believed that she attended a lower-

[Data source: Darley © Gross (1983)]

Half the participants (the no-

Which group do you think was especially likely to be influenced in their ratings by Hannah’s socioeconomic status—

And yet the opposite occurred, as we see in FIGURE 3.10. The objective evidence increased the bias rather than decreasing it. The group that didn’t have the opportunity to see Hannah perform estimated her math abilities to be the same regardless of whether she was upper or lower class. They seemed to realize that they didn’t have much basis for prejudging her abilities after only seeing her on a playground. However, the group that observed Hannah take an oral achievement test rated her much better if she was upper rather than lower class. These participants saw Hannah’s performance and rated her abilities in line with what they expected from a student of her social class. The point is that the participants didn’t interpret the so-

104

Biased Information Gathering

People’s schemas, even when tentative, can also lead to biased efforts to gather additional information, efforts that tend to confirm their preexisting schemas. Participants in one study had a brief discussion with a conversation partner who was described to them as being an extravert or an introvert (Snyder & Swann, 1978). Their job was to assess whether this was true, and they were given a set of questions to choose from to guide their conversation. Participants tended to ask the conversation partner questions that already assumed the hypothesis was true and would lead to answers confirming the hypothesis. For example, a participant wanting to determine if the partner was an extravert chose to ask questions such as, “What kinds of situations do you seek out if you want to meet new people?” and “In what situations are you most talkative?” However, if they wanted to determine if the partner was an introvert, they chose questions such as, “What factors make it hard for you to really open up to people?” and “What things do you dislike about loud parties?” What’s important to note here is that these are leading questions: When answering a question about how she livens up a party, for example, a person is very likely to come across as extraverted, even if she is not; likewise, even an extravert will look introverted when talking about what he dislikes about social situations. This study shows that people tend to seek evidence that fits the hypothesis they are testing rather than also searching for evidence that might not fit that hypothesis.

These effects could have important implications for how clinical psychologists diagnose disorders. In one series of studies, participants were shown a set of drawings of a human figure along with a psychological symptom of the person who drew each picture (Chapman & Chapman, 1967). After viewing all of the pictures, participants were asked to draw conclusions about whether people who share the same symptoms have a tendency to draw certain features of a person in a distinctive way. In a sense, they were given the opportunity to play amateur therapists who use drawings to uncover people’s psychological issues. And their responses showed a great deal of convergence: Participants often concluded that people with paranoid tendencies drew unusual eyes in their pictures, and men who were worried about their masculinity drew images with broader shoulders and more muscular physiques. However, unknown to the participants, the researchers had randomly paired each symptom with a picture so that there was no true correlation between these aspects of the drawings and the mental issues they imagined for the artists. Rather, they saw in the pictures what they expected to see given their expectations for paranoid or worried types. Follow-

The Self-fulfilling Prophecy

Another vivid testament to the power of schemas is evidence that they not only bias our perceptions of social reality, but can also create the social reality that we expect. More specifically, people’s initially false expectations can cause the fulfillment of those expectations, a phenomenon that Robert Merton (1948) labeled the self-

Self-fulfilling prophecy

The phenomenon whereby initially false expectations cause the fulfillment of those expectations.

105

Through a process known as the self-

[Darrin Henry/Shutterstock]

Two years later, the kids labeled as late bloomers actually scored substantially higher than their classmates did on a test of general abilities. However, unknown to the teachers, the list of kids originally labeled late bloomers was a random selection from the class rosters. So the only reason they experienced a dramatic intellectual growth spurt was that the teachers were led to expect they would!

What accounts for this self-

Since that classic study on teachers and students, self-

Limits on the Power of Confirmation Biases

We have beaten the drum for confirmation bias very loudly in this section, and the large body of evidence warrants doing so. However, confirmation biases do not always occur. If people’s observations clearly conflict with their initial expectations, they will revise their view of particular people and events. This is especially likely if the gap between what people expect and what they observe is very extreme. For example, if you play chess with a nine-

It is interesting, though, that even in such cases, people usually grant the exception but keep the underlying schema. In the chess example, you’d probably think, “This kid’s a genius, but most nine-

In addition, as we noted in the section on priming effects, when people are aware of and concerned about being biased, their cognitive system may kick in to correct the feared bias. Another way to think about this correction is to say that people’s need for accuracy trumps their need for closure, leading them to think more carefully—

106

Beyond Schemas: Metaphor’s Influence on Social Thought

So far we’ve focused on people’s use of schemas. It makes intuitive sense that people think about a thing by applying their accumulated knowledge about other things that are like it. But do people ordinarily use other cognitive devices to make meaningful sense of the social world? To find out, listen to how people commonly talk about the abstract ideas that matter in their daily lives:

I can see your point (understanding is seeing)

I’ll keep that in mind (the mind is a container)

Christmas is fast approaching (events are moving objects)

That is a heavy thought (thoughts are objects with weight)

I feel down (feelings are vertical locations)

I devoured the book, but I’m still digesting its claims (ideas are food)

Her arguments are strong (arguments are muscle force)

I’m moving forward with the chapter (progress is forward motion)

The economy went from bad to worse (states are locations)

These are metaphoric expressions because they compare things that, on the surface, are quite different. (These comparisons are reflected in the statements in parentheses.) That is why these expressions do not make sense if taken literally. For example, feelings do not have an actual vertical location, and arguments cannot have muscle strength. According to many philosophers and psychologists, such metaphoric expressions are more than merely colorful figures of speech; instead, they offer a powerful window into how people make sense of abstract ideas.

SOCIAL PSYCH out in the WORLD

A Scary Implication: The Tyranny of Negative Labels

A Scary Implication: The Tyranny of Negative Labels

In a 2013 episode of the radio program This American Life, Ira Glass (Glass, 2013) described the murder case of Vince Gilmer. In 2006, Gilmer was sentenced to life in prison and described by the judge as a “cold-

The good news about human nature is that extremely negative behavior such as Vince’s is actually rare. But because it’s so harmful or disruptive to society when people do bad or unusual things, we are quick to slap a negative label on those who commit crimes or who exhibit other abnormal tendencies and we are very reluctant to peel these labels off. Once someone is labeled a psychopath, as Vince was, his or her every action is interpreted as evidence of psychopathic tendencies. Negative or unusual behaviors seem fitting for a psychopath, but of course anything positive or exculpatory might also seem like a cunning attempt to charm and manipulate others. If the label is accurate, we tend not to stress about the mental straitjackets we apply to people. But these labels not only leave little room for people to grow beyond or redeem themselves from past wrongs, they also make it nearly impossible for those who have been mislabeled to break free of these binds.

In Vince’s case, it took someone who was willing to construct an impression or schema of him built around more positive associations to provide a different interpretation of what had happened to Vince. You see, before Vince killed his father, he was a beloved and compassionate doctor. The physician who took over Vince’s clinic learned about the close and caring relationships he had with his patients and dug into Vince’s case in more detail. Eventually, he discovered that Vince had tested positive for Huntington’s disease, a degenerative condition that could explain every one of the unusual behaviors, mood changes, and violent actions that Vince had been displaying over the past few years. Although Huntington’s is a terminal illness with no cure, and Vince Gilmer remains locked up in a psychiatric facility, Vince could finally feel vindicated that the label of cold-

Stories like Vince’s reveal the power of schemas to influence a person’s perceptions and lead to confirmation biases that justify whatever label she or he has already decided on. Of course, in Vince’s case, he had committed an unspeakable crime and was, in fact, exhibiting unusual and dangerous behavior.

Can negative labels be just as confining when inaccurately applied to sane and healthy people? Imagine the following horror film scenario: You wake up one day in a psychiatric institution and have been labeled a schizophrenic. How easy do you think it would be to convince the staff you were not schizophrenic and get them to release you?

In 1973, David Rosenhan set out to examine this very question in a provocative and controversial study. Rosenhan and seven other normal people checked themselves into San Francisco–

This study caused an uproar, partly because of qualms about whether it was ethical, but mainly because it illustrated that mental-

107

From this perspective, metaphors are cognitive tools that people use to understand abstract ideas by applying their knowledge of other types of ideas that are more concrete and easier to understand (Kövecses, 2010; Lakoff & Johnson, 1980). For example, when Lisa says, “Christmas is fast approaching,” she may be using her knowledge about moving objects to conceptualize time. Why? Because Lisa may find it difficult to get a clear image of time in her mind (not surprising, since physicists aren’t sure what time is!). Yet she has a concrete schema for physical objects moving around, and this schema tells her that objects tend to be more relevant as they draw closer. By using her objects schema to think about time, Lisa can make sense of what an “approaching” event means for her (time to buy gifts!), even though there is no such thing as an event moving toward her.

Metaphor

A cognitive tool that allows people to understand an abstract concept in terms of a dissimilar, concrete concept.

How does this perspective enhance what we know about social cognition? It suggests that people’s everyday efforts to construct meaning draw on metaphors as well as schemas. Whereas schemas organize knowledge about a given idea, metaphors connect an idea to knowledge of a different type of thing. Often, we construct metaphors around things that are connected to our bodily experiences. For instance, people understand morality partly by using a schema that might contain memories of moral and immoral individuals and behaviors. But people also understand morality metaphorically in terms of their bodily experiences with physical cleanliness and contamination (Zhong & House, 2013). This metaphor is reflected in common expressions such as, “Your filthy mind is stuck in the gutter; think pure thoughts with a clean conscience,” and it operates at a conceptual level to shape how we make judgments about morality.

Because metaphors connect seemingly unrelated concepts together, holding a warm cup of coffee might actually make you perceive other people as more warm and trustworthy.

[Africa Studio/Shutterstock]

108

Researchers have tried to go beyond analyzing language to learn more directly whether people use metaphor to think about abstract ideas. In one procedure, participants are primed with a bodily experience, such as tasting something, seeing something, or feeling something’s texture. Then, in an apparently unrelated task, they are asked to make judgments or decisions about an abstract idea. The researchers reason that if people in fact use a bodily experience to understand an abstract idea, then the prime should produce parallel changes in those judgments and decisions. To illustrate, if people understand love metaphorically as a journey (“Our relationship is moving forward”), then priming them with the bodily experience of journeying over rocky terrain (versus smooth terrain) should lead them to expect to encounter conflicts as their love relationships progress. Alternatively, if people do not use the metaphor love is a journey, then we wouldn’t expect that priming experiences of physical journeys would influence their judgments and decisions about love.

Williams and Bargh (2008) used this procedure to examine the metaphorical link between physical and interpersonal warmth. They built on prior evidence that people commonly refer to interactions with others by using the concepts warm and cold (Asch, 1946; Fiske et al., 2007), as when one receives a warm welcome or a cold rejection. To determine whether this metaphor influences social perceptions, they had the experimenter—

Similar effects have now been found in dozens of published studies (see Landau et al., 2010; Landau et al., 2013). Subtle primes of bodily experience influence how people perceive, remember, and make judgments and decisions related to a wide range of abstract social concepts. To mention just a few surprising findings: Weight manipulations influence perceived importance; smooth textures promote social coordination; hard textures result in greater strictness in social judgment; priming closeness (vs. distance) increases felt attachment to one’s hometown and families; groups and individuals are viewed as more powerful when they occupy higher regions of vertical space.

These findings highlight an important fact about the way we make sense of the world: We construct an understanding of abstract ideas by drawing on our knowledge of the sensory and motor experiences we have had from the earliest moments of life (Mandler, 2004; Williams et al., 2009).

APPLICATION: Moral Judgments and Cleanliness Metaphors

|

APPLICATION: |

| Moral Judgments and Cleanliness Metaphors |

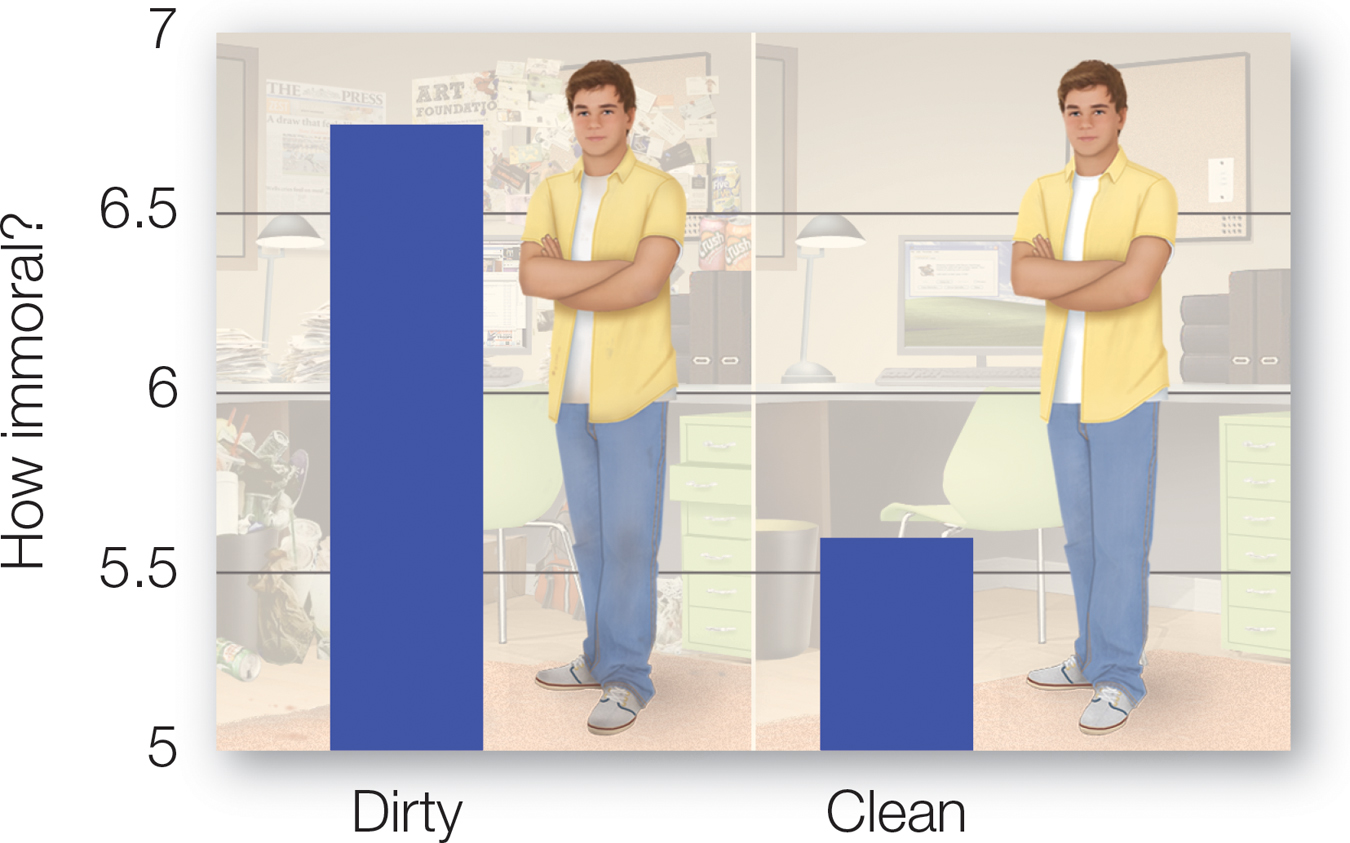

FIGURE 3.11

Moral Metaphors

When participants made moral judgments in a dirty work space, they judged moral violations more harshly than if the work space was clean.

[Data source: Schnall et al. (2008)]

Let’s look, for example, at how schemas and metaphors are applied in moral judgment. Your friend says her boyfriend lied to her and then asks you, “Wasn’t that wrong of him?” She is asking you to make a moral judgment—

109

But metaphor research suggests that our understanding of right and wrong, good and evil, may be affected by bodily concepts, particularly those related to disgust, physical filth, and cleanliness. Consider a study by Schnall and colleagues (2008). Participants were asked to read about individuals who committed various kinds of moral violations, such as not returning a found wallet to its rightful owner or falsifying a resume, and to rate how morally wrong those actions are. Half the participants made their judgments in a dirty work space: on the desk were stains and the dried-

|

The mind typically classifies a stimulus into a category, then accesses a schema, a mental structure containing knowledge about a category. Schemas allow people to “go beyond the information given” to make inferences, judgments, and decisions about a given stimulus. Although generally helpful, schemas can produce false beliefs and limit a person’s interpretation of reality. |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Sources Schemas come from multiple sources and are heavily influenced by culture. They are also shaped by the need for closure. |

Accessibility and Priming Salient schemas are highly accessible and color thinking and behavior. Priming occurs when activating an idea increases a schema’s salience. When primed, schemas can influence the impressions we form of others as well as our own behavior. Often these effects operate outside of conscious awareness. Priming can have contrast effects, leading to schema- |

Confirmation bias People tend to interpret information in a way that confirms their prior schemas. Objective information may be skewed to fall in line with expectations. Schema- Our expectations may shift another’s behavior toward confirming those expectations. We may revise our views for exceptional cases but retain the underlying schema. |

Metaphor People use metaphor to understand an abstract concept in terms of another type of idea that is more concrete and easier to grasp. |