13.2 Does Altruism Exist?

In an episode of the television show Friends, Phoebe is challenged by her friend Joey to find a way to help others that doesn’t in some way benefit her.

[Warner Bros TV/Bright/Kauffman/Crane Pro/The Kobal Collection]

The popular 1990s television show Friends had an episode in which the good-

479

Social Exchange Theory: Helping to Benefit the Self

Helping others can bring material benefits. Strong reciprocity norms all but guarantee that giving a little help to others might mean that you can count on them for help down the road. A social exchange theory approach to helping focuses on such egoistic motivations for helping. It maintains that people provide help to someone else when the benefits of helping and the costs of not helping (either to oneself or the other person) outweigh the potential costs of helping and the benefits of not helping (Thibaut & Kelley, 1959). It may sound like the kind of theory an accountant would dream up, but it is not so difficult to imagine carrying out this kind of mental calculation in some situations. Imagine that you are driving down the highway and see a car get a flat tire and pull off the road. Would you stop to help? Sure, you might be able to help the stranded motorist change his tire (a clear benefit to helping), but if you don’t stop, he will probably just call a tow truck (a rather low cost to not helping). You might feel good about yourself for helping (another benefit), but you could also end up getting pretty greasy and grimy on the side of the road (a clear cost). According to social exchange theory, the decision to help is determined by some quick mental calculations involving consideration of such benefits and costs.

Social exchange theory

An approach that maintains that people provide help to someone else when the benefits of helping and the costs of not helping outweigh the potential costs of helping and the benefits of not helping.

Think ABOUT

To study how people weigh costs and benefits in deciding whether or not to help, researchers in one study observed whether people helped a trained research assistant who collapsed on a subway. If you saw a stranger collapsed in a subway car or other public place, and he seemed to need help, would you come to his aid? When he carried a cane, he was helped within one minute in nearly 90% of the trials. When he appeared to be drunk, he was helped in fewer than 20% of the trials (Piliavin et al., 1969). Piliavin and colleagues argue that the reason we help is to reduce the arousal we feel when we see someone in distress. The costs of not helping an invalid seem much higher than the costs of not helping someone who is drunk. But the fact that someone needs help also can be offset by our aversion to situations or people we find disgusting or disturbing. In another subway collapse study, people helped less, and those who did took more time, if the person who had collapsed had blood trickling out of his mouth (Piliavin & Piliavin, 1972). Although the victim’s need for help was quite clear, people were reluctant to step forward when they might get bloody. Lending a hand also can cost us time, we might fear it’s a trap, or we might feel embarrassed if we do the wrong thing. When it’s a question of helping someone who is in physical danger, we might worry about our own welfare if we intervene to break up an argument or prevent an attack. All of these factors can weigh against helping when someone is in need.

According to the Dalai Lama, “If you want others to be happy, practice compassion. If you want to be happy, practice compassion.”

[Toru Yamanaka/AFP/Getty Images]

On the other side of the scale are the possible benefits of helping. Obviously the person in need stands to benefit from what you actually do. But there are other, less tangible benefits to helping. When the Dalai Lama received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1989, he included these words of wisdom in his acceptance speech: “If you want others to be happy, practice compassion. If you want to be happy, practice compassion.” Research backs up these words. People who generally feel compassion for others also feel better about themselves (Crocker et al., 2010). When people help others for intrinsic reasons, that is, reasons that align with their core values (see the discussion of self-

480

Empathy: Helping to Benefit Others

According to Daniel Batson’s empathy-

Empathy-altruism model

The idea that the reason people help others depends on how much they empathize with them. When empathy is low, people help others when benefits outweigh costs; but when empathy is high, people help others even at costs to themselves.

Is this true? Research shows that empathy can be an emotionally powerful experience. When people vicariously feel another person’s emotion, their brains show activation in the same areas that are activated when they themselves feel the same emotion (de Vignemont & Singer, 2006; Preston & de Waal, 2002). What’s more, studies show strong correlations between empathy and helping. For example, people are particularly likely to help others whom they feel similar to and like. These are also the people with whom they find it easiest to empathize (Batson et al., 2007; Coke et al., 1978). Also, do you remember how exposure to prosocial media, such as helping-

Thus, empathy is a powerful spur to prosocial behavior. But remember that the empathy-

One study examined whether similarity between the self and someone in need leads to feelings of empathy and, consequently, more helping, regardless of the costs of helping (Batson et al., 1981). Imagine you are a participant in this study. You arrive at a laboratory along with another participant named Elaine. After completing an initial preference survey, you learn that the two of you either share the same tastes in magazines and other preferences or have very different tastes. Elaine is randomly assigned to complete a performance task under stressful circumstances; you are assigned to observe and form an impression of her either during the entire study or only during her first set of trials. It sounds pretty straightforward. But the stress that Elaine is exposed to consists of repeated mild but painful electric shocks. After her first round of shocks, Elaine is obviously anxious and explains that she is unusually fearful of electricity. The experimenter isn’t sure what to do but after giving it some thought turns to you and suggests that perhaps you could switch places with Elaine. Would you volunteer? Would it matter whether you feel similar to or dissimilar to Elaine? Would it matter if you were not going to have to watch her take any more shocks or if the study procedure called for you to observe a second round of trials?

481

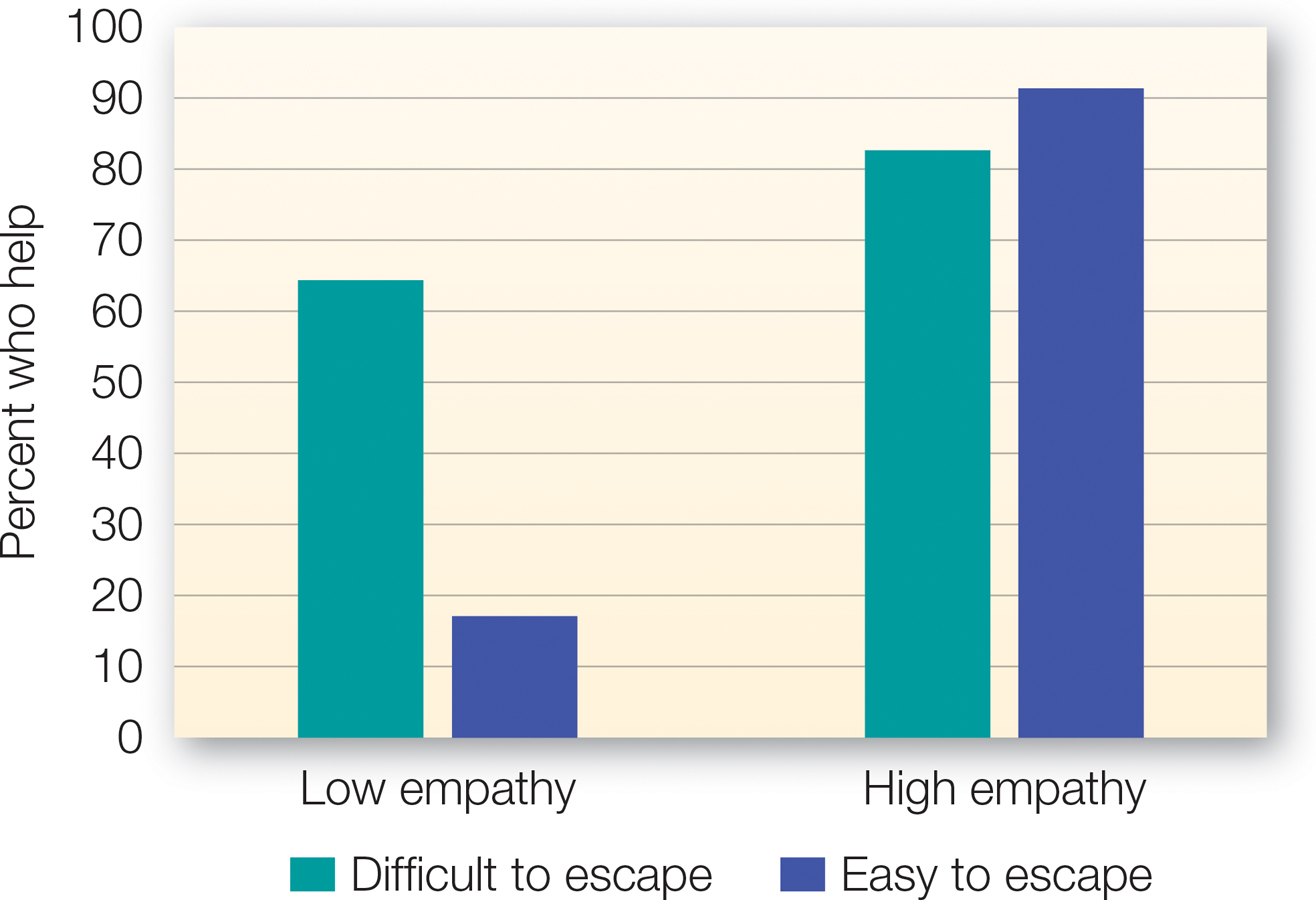

FIGURE 13.1

People Help When Either Empathy or the Cost of Not Helping Is High

This study by Batson and colleagues shows us that empathy is a key catalyst for helping. When people were low in empathy (on the left), they helped only if they would suffer by not helping. However, people high in empathy (on the right) helped regardless of the costs of not helping.

[Data source: Batson et al. (1981)]

Look at the two bars on the left of FIGURE 13.1. When people didn’t feel especially similar to Elaine and so were not likely to feel empathy for her, 64% volunteered to trade places with her if they would otherwise have to watch her endure another set of shocks. However, if they didn’t have to watch her take any more shocks, it was easy for them simply to leave the study, and in fact only 18% stayed to help. In the absence of empathy, these participants relied on a cost-

Feeling empathy for someone in need is an important precursor to providing help, and as we just saw, it will lead people to step up even at some cost to themselves. But sometimes, people might perceive the costs as being too high. In these cases, people will sometimes choose to avoid experiencing empathy in the first place. For example, in one study, participants were told that they could choose to listen to one of two personal appeals from a homeless man, one that would likely make them empathize with his plight or a more objective account of his situation (Shaw et al., 1994). When making this choice, some participants were aware that later they would have to decide whether to volunteer either an hour of time writing fund-

Negative State Relief Hypothesis: Helping to Reduce Our Own Distress

Although Batson has been a champion of altruism, critics have argued that empathy is not always about what another person feels. They grant that when people empathize with someone in need, they feel that person’s pain. But they point out that the pain becomes their pain, such that the motivation to help really traces back to reducing one’s own pain—

Negative state relief hypothesis

The idea that people help in order to reduce their own distress.

482

SOCIAL PSYCH at the MOVIES

Prosocial Behavior in The Hunger Games

Prosocial Behavior in The Hunger Games

Imagine this: You and 23 other people are competing in the biggest reality TV show ever created. The stakes are life and death, and only the strongest survive. Worse yet, you are forced to play, and there can be only one winner. What would you do?

This is the premise of the film The Hunger Games (Collins et al., 2012), based on the popular novel, the first of a trilogy by Suzanne Collins (2008). The time is the distant future. The Capitol government rules over the nation of Panem. To punish lower-

The story’s first remarkable prosocial act occurs when the protagonist, Katniss Everdeen (played by Jennifer Lawrence), steps forward to take the place of her beloved 12-

We also witness characters who are not genetically closely related helping one another. In one scene, Katniss has been chased up a tree by an alliance of vicious, highly trained Tributes from other districts. Her goose appears to be cooked until 12-

Another scene illustrates the power of empathy to spur altruism. Prior to entering the arena, Katniss is mentored by Haymitch Abernathy (Woody Harrelson). Later, while watching the Hunger Games on TV, Haymitch sees Katniss in agonizing pain after she is injured in battle. This prompts him to petition a sponsor from Panem’s elite class to have a healing balm delivered to Katniss. Why does he take the time and energy to do this? He does not personally benefit, and Katniss had done nothing special to deserve his favor. Empathy seems to be the answer. Because Haymitch is a former victor in the Hunger Games, he can easily put himself in Katniss’s shoes and feel her pain and fear. When he sees her wince in pain, he winces too. He may help simply to stop feeling bad (in keeping with the negative state relief hypothesis), but he could just as easily distract himself from Katniss’s plight to do so. So his actions more likely result from empathy, a genuine concern for another’s well-

Perhaps the most profound displays of prosocial action occur between Katniss and Peeta Mellark (Josh Hutcherson), the male Tribute from District 12. Throughout the Hunger Games, Katniss and Peeta put their own lives in great danger to help and protect one another. One basis for this may be their shared social identity of being from the same District. But beyond that, Peeta is clearly in love with Katniss. Katniss’s feelings for Peeta are more ambivalent, but their affection and consequent empathy is increasingly reciprocated over the course of the Games. As the research on rescuers of Jews during the Nazi era found, affection is a common basis for empathy and helping, and this may be especially true when feelings of romantic love are involved. In addition, such feelings may signal the possibility of reproduction. If so, we may be prepared to offer help to those with whom we fall in love.

The ultimate problem for Katniss and Peeta is that there can be only one survivor of the Games. In case you are one of the few who haven’t seen this film, we won’t reveal how that dilemma is resolved.

Okay, Altruism: Yes or No?

The debate over the existence of a pure altruistic motive consumed research on prosocial behavior during the 1980s, with papers from one camp shot like can-

483

When the dust from all of these studies settled, what did we learn? Researchers use meta-

484

|

Does Altruism Exist? |

|

Researchers have studied whether genuine altruism exists or whether prosocial behavior is done for one’s own benefit. |

||

|---|---|---|

|

The social exchange theory People do a quick cost- |

The empathy- People can feel empathy, and this empathy leads to genuinely altruistic acts. |

The negative state relief hypothesis Helping triggered by empathy is still egoistic because it reduces one’s own pain. However, meta- |