13.4 Priming Prosocial Feelings and Behavior

Evolutionary perspectives on helping provide insight into how prosocial tendencies and associated emotions may have become part of human nature. Social learning perspectives provide insight into how helpfulness is learned and transmitted within a given culture or social environment. We might think of evolutionary processes as giving us the basic machinery to be helpful and of social learning as providing us with culturally specific scripts for how to be helpful. But we still need situational accounts to provide insight into when we enact these scripts and when we do not. The story of when we help is based partly on our relationships with others and partly on the emotions triggered in social situations. As we’ve seen in several places throughout this book, however, even very subtle situational cues can activate behavioral scripts outside our conscious awareness. The same is true of prosocial behaviors. Let’s review a few of the subtle ways in which people can be primed with prosocial scripts.

Positive Affect

One of the earliest lines of studies examining what primes people to be prosocial looked at the effect of positive mood. You no doubt can recall an experience when you felt bright and cheerful, whistling as you walked down the street, quite willing to spend your time stopping to help someone pick up their spilled groceries or digging into your pockets to give your spare change to a panhandler. If your intuitions tell you that you’ll be more helpful in a positive mood, research by Alice Isen suggests you are right. Whether participants’ positive mood arose from succeeding in a difficult task, receiving cookies, or unexpectedly finding a dime in a pay phone (note to the perplexed: There used to be booths with phones in them that accepted coins as payment for a call), they were more likely to help afterward. They give more money to charities, offer more assistance to someone who has spilled their belongings, and are more likely to buy a stamp and mail a letter that has been left behind (Isen, 1970; Isen & Levin, 1972; Levin & Isen, 1975). Like most priming effects, these can be transient, dissipating once people’s mood returns to baseline (Isen et al., 1976).

490

If you did have the intuition that people are more helpful when they are happy, can you spell out why that would be the case? What is it about being in a good mood that makes people more prosocial? Several processes might be in play (Carlson et al., 1988). On the one hand, good moods are inherently rewarding, making people loath to do anything that might knock them out of that mood. Consequently, when people are in a good mood they may help in order to avoid the guilt that would arise if they turned their backs on someone in need. In addition to this rather selfish influence, happy moods make people see the best in other people. With this more positive frame of reference on humanity comes a more prosocial orientation and a tendency to see the inherent good that comes from lending a helping hand (Carlson et al., 1988).

Prosocial Metaphors

Many concepts related to prosocial behavior, such as morality and fairness, are inherently abstract and difficult to grasp in their own terms. As we discussed in chapter 3, people often make sense of abstract concepts using metaphor. Metaphor is a mental tool that people use to think about and understand an abstract concept by using their knowledge of a different type of concept that is more concrete and easier to comprehend.

Do people use metaphor to understand concepts related to prosocial behavior? Many common expressions about these concepts suggest that they do. Take, for example, the relationship between morality and vertical height. Being moral does not mean literally being higher in space. Still, people talk about taking the “moral high ground” to refer to virtuous behavior, and when they watch or hear about heartwarming stories of altruism such as those we described at the beginning of this chapter, they talk about feeling “uplifted.” In general, people organize their moral view of the world by ranking different beings along a vertical dimension, putting the most moral agents, such as god(s), at the top and animals who they think lack any moral compass at the bottom (Brandt & Reyna, 2011).

If people think about the abstract concept of morality in terms of a concrete state (e.g., being at a high altitude or clean), then situations that prime that state should change how people think about morality and thus affect their willingness to lend a hand. Height is one way to prime morality; cleanliness is another. When we behave immorally, we feel dirty. Lady Macbeth, tortured by her conscience after goading Macbeth to murder the king, cries “Out, damn’d spot!” as she compulsively washes her hands over and over again in Shakespeare’s Macbeth (1606/1869). If we associate “dirtiness” with immoral behavior, then we might associate “cleanliness” with virtuous, prosocial behavior. After all, cleanliness is next to godliness, or so they say. Primed with the fresh scent of window cleaner, participants in one study reported a greater interest in volunteering for Habitat for Humanity, and they actually donated more money to that charity than did participants in an unscented room (Liljenquist et al., 2010). If you need to ask a favor of a friend, you might want to bring along a little Windex to seal the deal!

Priming Prosocial Roles

Some social roles and occupations, such as nursing, carry with them the norm to be helpful. When people take on those roles, or simply bring them to mind, they become more helpful.

[michaeljung/iStock/360/Getty Images]

Social roles and relationships come with certain norms that tell us how to behave. For example, when you take the role of friend, that role carries the norm that you will help more than when you take the role of stranger or coworker. If people commit themselves to a helping profession such as teaching, nursing, or customer service, taking on that role should also prepare them to be helpful. What’s more surprising are the subtle ways that these prosocial roles and relationships can be primed. In one study, people at an airport were asked to do a quick survey in which they recalled and answered a few questions about either a close friend or a coworker. Afterward, they were merely asked to rate their interest in helping the experimenter by completing a second, longer survey. Only 19% agreed when they were first primed to think of a coworker, but 53% agreed when first primed with a friend (Fitzsimons & Bargh, 2003). You might say that thinking about friendship puts us in a friendly state of mind and readies us to act in a friendly, helpful way. We might even be more likely to incorporate these subtle cues into our behavior when we otherwise feel deindividuated or disinhibited (Hirsh et al., 2011). Just as people can become more aggressive when they feel deindividuated but are primed with an aggressive role, they can become more prosocial when they feel deindividuated and are primed with a caregiving role, like being a nurse (Johnson & Downing, 1979).

491

Priming Mortality

A pale light . . . fell straight upon the bed; and on it . . . was the body of this man. . . . Oh cold, cold, rigid, dreadful death!. . . But of the loved, revered, and honoured head, thou canst not turn one hair to thy dread purposes. . . . It is not that the hand is heavy and will fall down when released. . .but that the hand was open, generous, and true; the heart brave, warm, and tender. . . . [S]ee his good deeds springing up from the wound, to sow the world with life immortal!”

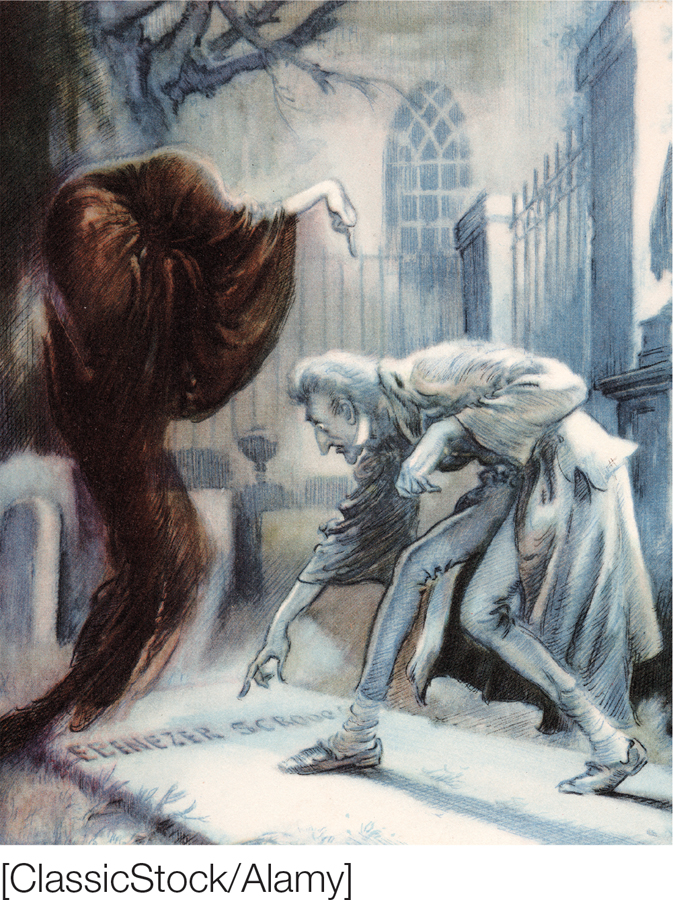

In the classic Charles Dickens tale A Christmas Carol, the stingy Ebenezer Scrooge is ultimately moved to become a charitable person by the ghost of Christmas Future, which shows him his fate: to be forgotten after his death.

[ClassicStock/Alamy]

—Charles Dickens, A Christmas Carol (1843/1950, pp. 115–

Most of us are socialized to try to do the right thing. Cultural worldviews usually if not always promote helping as the way to be a good, valuable person. Consequently, helping behaviors normally contribute to our sense of significance in the world and of creating a legacy of positive impact into the future, even beyond our own lives. By applying an existential perspective, terror management theory therefore suggests that mortality salience should promote prosocial behavior. In the classic Charles Dickens tale A Christmas Carol, the stingy Ebenezer Scrooge is ultimately moved to become a charitable person by the ghost of Christmas Future, which shows him his fate: to be forgotten after his death. He realizes that generosity will ensure that he has a positive impact and will be remembered beyond his physical death.

Will reminders of mortality generally make people more generous? In support of this “Scrooge effect,” studies by Jonas and colleagues (2002) have shown that mortality salience increases donations to valued charities. A study at a university library similarly showed that a flier reminding passersby of their mortality made them more willing to help a psychology student complete her research project (Hirschberger et al., 2008). Consistent with these experiments, real-

Priming Religious Values

When it comes to priming moral behavior, some of the most potent concepts come from religion. Religion, like culture more generally, gives people a set of rules and restrictions that help regulate their behavior. Religious teachings explain what it is to be a good and moral person and almost invariably preach kindness and compassion. Indeed, the notion that we should do unto others as we would have them do unto us captures our basic prosocial norm for positive reciprocity and can be found in all of the major world religions (Batson et al., 1993). The problem is that true reciprocity only really works with people we see and interact with on an ongoing basis. When societies got big, people found themselves having more and more onetime interactions with complete strangers. These large societies function better if we expand our notion of reciprocity to people we do not know. Big religions help do this by incorporating the message of reciprocity as a general principle, a “golden rule” (Norenzayan & Shariff, 2008; Shariff et al., 2010).

492

Does this then imply that those who are religious act more prosocially? Not necessarily. It’s true that people who report high levels of religiosity also report being more altruistic, but in laboratory settings designed to measure the likelihood of helping, religiosity is unrelated to the actual likelihood of prosocial actions (Batson et al., 1993). Other work points to competing values associated with religiosity, at least in the United States (Malka et al., 2011). On the one hand, religiosity in America is associated with conservative ideologies that tend to oppose social welfare policies. Religious individuals also tend to make dispositional attributions (Jackson & Esses, 1997), which as we discussed earlier, can make people less likely to help a person out. However, religiosity is also associated with prosocial values that predict increased support for social welfare. These competing cultural messages indicate that the relationship of religiosity to helping is not so clear cut.

Even if we can’t always count on religious adherence to predict prosocial practices, the mere idea of religion can still prime more positive acts. Participants who first unscrambled sentences that primed them with concepts such as “divine” and “sacred” were more generous to a stranger than those primed with neutral concepts (Shariff & Norenzayan, 2007). This effect was present even for those who report being atheists, although it is interesting that priming people with other ways that society promotes justice (“courts” and “contracts”) had the same effect. In fact, one of the ways that concepts of deities might help us keep on the moral path is by giving us the sense that someone is always watching what we do, keeping track of when we are naughty or nice (Gervais & Norenzayan, 2012).

We can also view religion as defining our cultural worldview, one we are motivated to uphold when reminded of our mortality. Although religious fundamentalism often is associated with prejudice and intolerance toward other groups, people primed with the more compassionate side of their religious ideals are in fact more likely to turn the other cheek. When reminded of their mortality and primed with compassionate values, fundamentalist Christian Americans were less supportive of using extreme military force to defend the homeland against attack (Rothschild et al., 2009). In this way, religion can play an important role in promoting prosocial behavior even toward those who do not share the same religious worldview.

|

Situations can trigger helping behaviors, even without our awareness. Prosocial behavior is increased by: |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Positive moods that put people in a prosocial mindset. |

Physical cues (e.g., clean scents) that are linked to prosocial concepts by means of metaphor. |

Friends and primes of friendship that cue a communal orientation. |

Reminders of mortality that lead people to help someone who supports their worldview. |

Priming religion or religious values, although the relationship between dispositional religiosity and helping is more complicated. |

493