14.2 The Basics of Interpersonal Attraction

Now that we have established the importance to people of forming social relationships, we can address how people choose others with whom to develop such relationships. Note that for the most part we’ll be focusing on social relationships, which include friendships as well as both opposite-

Proximity: Like the One You’re With

One simple determinant of social relationships is known as the propinquity effect, propinquity meaning closeness in space. The original idea was that you can’t form a relationship with someone unless you meet them, and the closer you are physically to someone else, the more likely you are to meet and therefore form a relationship with him or her.

Propinquity effect

The increased likelihood of forming relationships with people who are physically close by.

With the proliferation of Internet technology in many contemporary cultures, this is not so true anymore. Facebook, Twitter, blogs, message boards, and other apps make it more and more possible to form relationships with people we rarely, if ever, actually meet. This includes people from around the globe and in cyberspace with whom we share an interest. Before the Internet, people sometimes developed relationships with “pen pals,” friends known only through an exchange of letters. So for a long time, physical propinquity has not been necessary for developing a social relationship; nevertheless, it’s less important, at least for casual relationships, than ever before. At the same time, face-

The power of proximity. In many contexts, such as apartment complexes, you are randomly placed near some people and far from others. Nevertheless, physical location powerfully predicts who you are attracted to and form relationships with.

[Lisa Werner/Alamy]

512

With these caveats in mind, it’s still worth considering the role of proximity. The first empirical breakthrough in examining this factor was a study by Festinger and colleagues (1950). They interviewed residents in a new apartment complex. As in most apartment complexes, the apartment manager had placed residents in their particular apartments in an essentially random fashion. Festinger and colleagues saw this as a natural experiment that gave them the opportunity to study whether and how proximity influences friendship formation. They found that the physical location of one’s apartment within the complex had a large impact on who made friends with whom and on how many friendships one formed within the complex. For example, people were nearly twice as likely to form a friendship with the person in the next-

Festinger and his colleagues also found that among people who lived in first-

A number of explanations have been offered for the surprising impact of physical location. One is based on familiarity. As you may recall from chapter 8, evidence supporting the mere exposure effect shows that we tend to like novel stimuli better the more we are exposed to them (Zajonc, 1968). The unfamiliar makes most people initially wary or even anxious. As a stimulus becomes more familiar, people feel more at ease, and that positive feeling becomes associated with the stimulus. In the case of interpersonal interactions, the more you see a new person, the more positive you are likely to feel about that person. Because you’ll see your next-

An Oregon State speech professor demonstrated the benefits of familiarity by having someone come to his class every day in a big black bag (Rubin, 1973). At first, the students were wary of the human black bag and sat as far away as possible. However, by the end of the course, the students were very friendly with the black bag and treated it like a beloved class mascot. Moreland and Beach (1992) assessed this phenomenon more systematically. They had typical college-

513

More recently, Reis and colleagues (2011) systematically varied how many chats, ranging from 1 to 8, participants had with a same-

A related explanation for the proximity effect is that, in general, casual interactions with other people are mildly pleasant. You exchange greetings, perhaps commiserate about the weather, or discuss the fortunes of the local sports teams. The more mildly pleasant conversations you have, the more positive feelings you will associate with the person with whom you are conversing.

Of course, there are important exceptions to the proximity effect—

The Reward Model of Liking

The core idea of the reward model of liking is simple: We like people we associate with positive feelings and dislike people we associate with negative feelings (e.g., Byrne & Clore, 1970; Lott & Lott, 1974). It is basically a classical conditioning model of liking, similar to the influences on persuasion we talked about in chapter 8. Recall that advertisers often will pair their product with an uplifting jingle or cute scene, trying to foster a positive association with the product. In the reward model, a new person begins as a relatively neutral stimulus. If exposure to the person is temporally linked to a second stimulus you already like, the positive feelings evoked by the second stimulus start to become evoked by the person. Conversely, if the second stimulus evokes negative feelings in you, some of those negative feelings start to become linked to the person. This raises the question, What are these second stimuli that influence our liking for others?

Reward model of liking

Proposes that people like other people whom they associate with positive stimuli and dislike people whom they associate with negative stimuli.

This messenger might be a jerk, but the reward model suggests that this woman will like him if she associates him with the positive feelings evoked by the package.

[Tyler Olson/Shutterstock]

When we think of why we like someone, we usually talk about that person’s attributes, and that is certainly part of the total picture. But the reward model suggests that we could come to like (or dislike) someone not because of any attribute they have or behavior they engage in, but simply because they happened to be around when we were feeling good (or bad). The idea seems to fit the rather unfair practice of ancient Roman rulers who sometimes would kill messengers who brought bad news (prompting the old expression “Don’t kill the messenger”).

One early test of this idea had participants simply sit in a room for 45 minutes and fill out some questionnaires. One of the questionnaires described a stranger’s attitudes on various issues. The experimenter varied the temperature in the room so that it was either comfortable or unpleasantly hot. Participants were then asked to indicate how they felt about the stranger. As the reward model predicts, participants liked the stranger better if the room was comfortable than if it was not (Griffitt, 1970). Researchers have used a variety of other methods to make the same point. For example, one study had participants overhear bad or good news on a radio broadcast and then evaluate a stranger (Veitch & Griffitt, 1976). They liked the stranger better if the radio broadcast good rather than bad news. So sometimes, we may like or dislike someone because they just happen to be there when something pleasant or unpleasant happens to occur.

514

We probably overlook these sorts of influences most of the time in thinking about why we like or dislike someone, because we focus on that person’s attributes. On the other hand, most of us also probably have some intuition that feelings created by things we don’t cause can rub off on how people feel about us. For example, if you are going on a first date with someone—

Others’ Attributes Can Be Rewarding

Having acknowledged the role of situational factors, we next ask, What attributes of people themselves evoke the positive feelings that increase our attraction to them? Most of the research on interpersonal attraction addresses this question in one way or another.

Transference

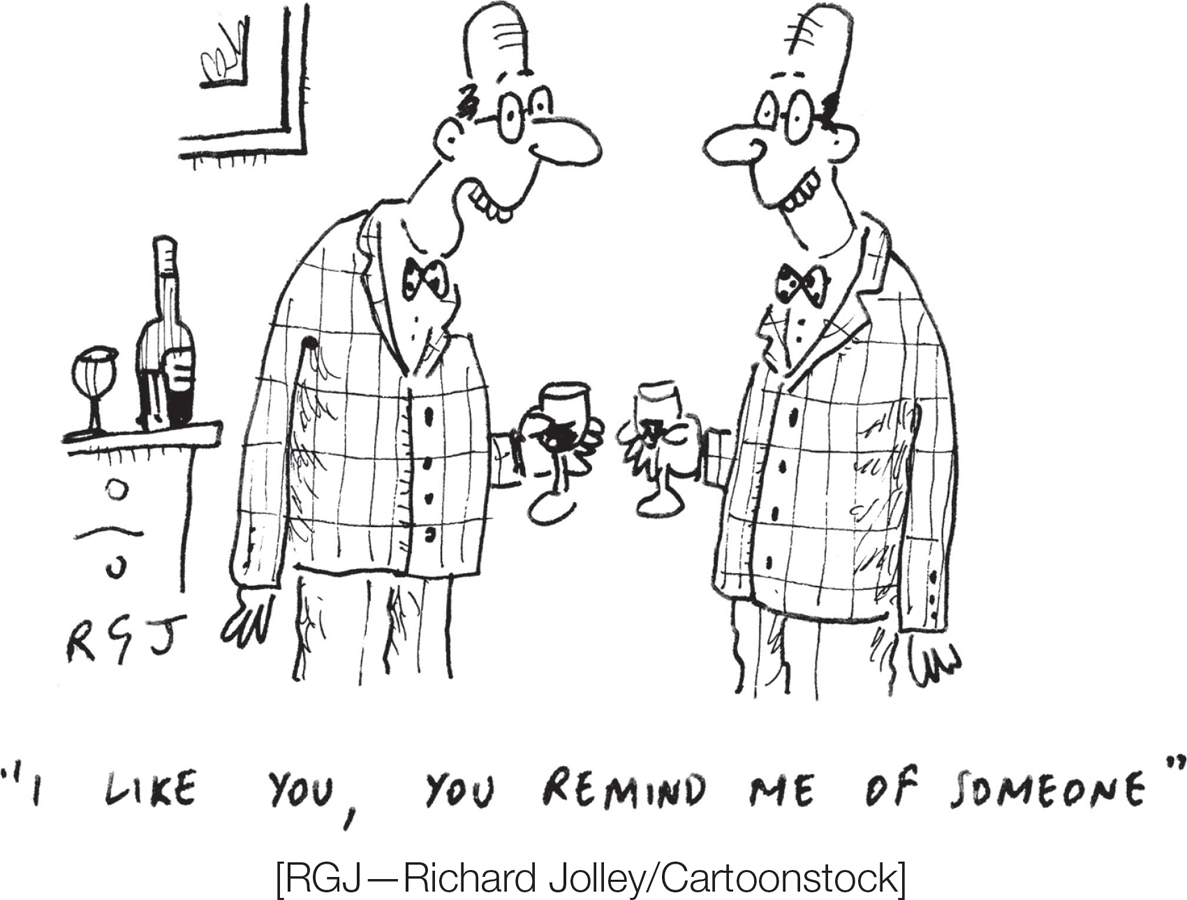

First, some attributes may evoke positive feelings because we associate them with people we like or positive experiences we had in the past. For example, Collins and Read (1990) found that people are often drawn to romantic partners who have a caregiving style similar to that of their opposite-

Transference

A tendency to map on, or transfer, feelings for a person who is known onto someone new who resembles that person in some way.

Culturally Valued Attributes

As cultural animals, we also are drawn to people who have talents or have achieved things that our culture values (e.g., Fletcher et al., 2000). Celebrities are an extreme example. Many if not most people are fascinated by celebrities because the culture has deemed them to be of great value—

515

This form of attraction extends not only to the extremes of celebrity but also to any attributes highly valued. In the United States, these include such things as wealth, beauty, musical or athletic talent, and so forth. Acquiring a so-

Personality Traits

Next, let’s consider personality traits. Across a wide range of studies, people generally report preferring certain traits in their partners and friends. Not surprisingly, these include friendliness, honesty, warmth, kindness, intelligence, a good sense of humor, emotional stability, reliability, ambition, openness, and extraversion (e.g., Sprecher & Regan, 2002). The culture promotes the valuing of these traits. In addition, it’s easy to imagine how people with any of these desirable traits could evoke positive feelings in us, and, by the same token, how people with the opposite traits might evoke negative feelings in us. Which traits people desire in others depends to some extent on their relationship with the other person. For example, people report that agreeableness and emotional stability are more valued in a close friend than in a study group partner, whereas intelligence is reported to be more valued for a study group partner than for a close friend (Cottrell et al., 2007).

Although research on the traits we like in an ideal partner is valuable, we should note that the vast majority of this work assesses what traits people report or think they like, not those that they actually like (Eastwick et al., 2013). This is because the best test of what attributes people actually like would be very difficult, if not impossible, to conduct. You would have to assign people randomly and have them get to know other people who systematically vary in these traits to really sort out what attributes people like and dislike in others.

We make this point because the cultural worldview we learn as children teaches us that kindness, intelligence, honesty, and so forth are good qualities. Thus, our self-

One method that tries to tease apart reported and actual preferences is to create a situation that resembles speed dating. In one set of studies, Eastwick and colleagues (Eastwick, Eagly et al., 2011; Eastwick, Finkel et al., 2011) had male and female participants sit at individual tables as a parade of potential partners (or “dates”) rotated through, spending about 4 minutes with each participant. Later, the participants were asked whom they would have liked to see again. The researchers found that the traits the participants reported caring about in a prospective romantic partner failed to predict how interested they were in others who had or did not have those qualities when they met them face to face.

516

Each of these people likely came into the speed-

[CB2/ZOB/Supplied by WENN.com/Newscom]

Of course, speed-

Once we acknowledge these caveats, Eastwick and colleagues’ findings may help explain why finding a date or friend online might not work (Finkel et al., 2012). You get all sorts of information about what the person is like before you even meet. It seems very handy. But this research suggests what we think we like doesn’t necessarily predict whether things will go smoothly when we meet that person face-

Attraction to Those Who Fulfill Needs

Beyond having talents, achievements, and desirable traits, people also can be attractive to us because they help to satisfy our psychological needs. One is the need to sustain faith in a worldview that gives meaning to life. Another is to maintain a strong sense of self-

Similarity in Attitudes

One of the strongest determinants of attraction is perceived similarity. As the old saying goes, “Birds of a feather flock together.” Similarity on several dimensions matters. People who become friends, lovers, and spouses tend to be similar in socioeconomic status, age, geographical location, ethnic identity, looks, and personality (Byrne et al., 1966; Caspi & Herbener, 1990; Hinsz, 1989). But particularly powerful is similarity in attitudes and overall worldview. Imagine Lana, a Republican Christian young woman who is against abortion and is a supporter of low taxes, a strong military, and gun rights. She likes country music and soft rock, skiing, tennis, action movies, designer clothes, fine wine, and Italian food. She meets Rosa and Erica at a party. Rosa is a Republican Christian who supports the same issues, who likes country music, tennis, action movies, fine clothes, and (OMG) Italian food. Erica is a Democratic agnostic who is prochoice and antigun, and likes hip-

Rosa, of course. She validates Lana’s beliefs about the way the world works, what good music sounds like, what makes for a good meal, and so forth. In having similar beliefs and preferences, she bolsters Lana’s worldview and self-

We like to be around people who share our attitudes and interests because it validates our view of the world.

[From left to right: © Tommy (Louth)/Alamy; Roger Cracknell16/Glastonbury/Alamy; Mark Ralston/AFP/Getty Images]

517

It is interesting to note that the causal arrow works both ways. Just as perceived similarity increases attraction, attraction increases perceived similarity. If we like someone, we also tend to assume he or she has similar attitudes (Miller & Marks, 1982). In addition, couples tend to think their attitudes are more similar than they actually are (Kenny & Acitelli, 2001; Murray et al., 2002).

Perceived Versus Actual Similarity

Several studies show that what is important for attraction and relationship commitment is how much people perceive that they are similar to another, and not necessarily how similar they are from an objective point of view (Montoya et al., 2008). For example, people’s initial attraction in a speed-

Why is actual personality similarity not very predictive of attraction and relationship satisfaction, whereas perceived similarity is? Perhaps the answer lies in that old trope that “opposites attract.” This idea has some intuitive appeal. Shouldn’t someone who likes to make decisions get along with someone who doesn’t? Shouldn’t someone given to emotional ups and downs fit with someone very stable and consistent? In other words, shouldn’t people who have complementary qualities get along (Winch, 1958)? Of course, dissimilar people sometimes will hit it off as friends or romantic partners, but most evidence suggests this is more the exception rather than the rule.

However, a few studies show ways in which opposites may attract. One way is that highly masculine men tend to be attracted to highly feminine women (Orlofsky, 1982). In addition, Dryer and Horowitz (1997) found in two studies that after a brief interaction, female students high in dominance preferred a submissive partner, and females high in submissiveness preferred a dominant partner. So it appears that for the traits of dominance and submission, complementarity contributes to attraction. The same applies to fiscal habits: People who tend to scrimp and save often marry people who like to spend. Still, their different spending styles contribute to conflicts over finances, which reduce marital well-

Tesser’s (1988) self-

518

Similarity in Perceptions

So far, we’ve been talking about similarity (perceived or actual) in personality traits, demographic characteristics, behavioral preferences, or attitudes. These are all features of the self that William James called the “Me.” But recall that James distinguished what the self is in terms of the content of who we are (the Me) from our subjective point of view on the world around us (the I). According to Liz Pinel and colleagues (Pinel et al., 2004), we “Me-

By way of example, your current author once joined a crew tasked with painting the interior of non-

I-

If You Like Me, I’ll Like You!

Other people, particularly those we respect or care about, can bolster or threaten our self-

In chapter 13 we discussed the norm of reciprocity. This idea extends to liking. All else being equal, if you find out that someone else likes you (more than he or she likes others), it makes you more likely to like them too (Condon & Crano, 1988; Curtis & Miller, 1986; Eastwick et al., 2007). In one study, people’s reports of how they fell in love or formed a friendship with a person indicated that a key factor was realizing that the other person liked them (Aron et al., 1989). In fact, when compared with attitude similarity, being liked by another is a stronger initial factor in attraction (Condon & Crano, 1988; Curtis & Miller, 1986). One obvious explanation for the reciprocity of liking effect is based on self-

519

Flattery

It’s no surprise that we also like people who compliment us, even to the point of flattery. Studies show that the more nice things someone says about us, the more we like them (Gordon, 1996; Jones, 1990). The benefits of flattery even extend to computers. When participants received randomly generated positive performance evaluations from a computer, they liked the computer better—

Flattery doesn’t always work, however. If it is clear the flatterer has an ulterior motive, the compliments are not quite so effective (Gordon, 1996; Matsumura & Ohtsubo, 2012). Still, we generally prefer someone who says nice things about us (even if that person’s motives are suspect) to someone who doesn’t have anything nice to say at all (Drachman et al., 1978). This is because any compliment will still make us feel good (Chan & Sengupta, 2010). We usually are more motivated to embrace positive feedback than to question its validity (Jones, 1964, 1990; Vonk, 2002).

Aronson and Linder’s gain-

Gain-loss theory

A theory of attraction that posits that liking is highest for others when they increase their positivity toward you over time.

Aronson and Linder tested this hypothesis by having participants overhear a series of evaluations of them by a discussion partner who was a confederate of the experimenter. There were four patterns of evaluations: consistently positive, consistently negative, initially negative and then becoming positive (gain), and initially positive and becoming negative (loss). The participants liked the confederate best in the gain condition, second best in the consistently positive condition, even less in the consistently negative condition, and least in the loss condition. Positive judgments from someone who was initially negative and negative judgments from someone who was initially positive polarized people’s attitudes for the evaluator. Aronson and Linder noted that this phenomenon may put a long-

What other aspects of the person giving us compliments affect how much we like him or her? One saying floating around in our culture is that “playing hard to get” can increase one’s attractiveness. Evidence doesn’t generally support that idea, but it does support the idea that people are more attractive if they seem hard for others to “get” (Eastwick et al., 2007; Wright & Contrada, 1986). Some people are very free with compliments and seem to like everybody. Other people are very discriminating, doling out compliments only to the lucky few. Compliments and liking increase attraction more if the person giving them out seems discriminating rather than giving out compliments freely or seeming to like virtually everyone.

520

|

The Basics of Interpersonal Attraction |

|

Several factors affect how we choose others with whom we form close relationships. |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Proximity Physical proximity is an important factor in developing relationships, although its importance is tempered by social media. |

Reward model People like others whom they associate with positive feelings and dislike those associated with negative feelings. |

Attributes of the person People like those who remind them of others they like. People like those with culturally desirable attributes. Self- |

Our psychological needs People tend to like others who fulfill their needs for meaning and self- are perceived as similar to the self. reciprocate liking. flatter them. |