Chapter Introduction

| CHAPTER | 13 |

Prosocial Behavior

470

471

TOPIC OVERVIEW

-

Human Nature and Prosocial Behavior

SOCIAL PSYCH OUT IN THE WORLD A Real Football Hero Learning to Be Good

-

Social Exchange Theory: Helping to Benefit the Self

Empathy: Helping to Benefit Others

Negative State Relief Hypothesis: Helping to Reduce Our Own Distress

Okay, Altruism: Yes or No?

SOCIAL PSYCH AT THE MOVIES Prosocial Behavior in The Hunger Games The Social and Emotional Triggers of Helping

Similarity and Prejudice

The Empathy Gap

The Role of Causal Attributions

Other Prosocial Feelings

Priming Prosocial Feelings and Behavior

Positive Affect

Prosocial Metaphors

Priming Prosocial Roles

Priming Mortality

Priming Religious Values

-

The Bystander Effect

Steps to Helping—

or Not!—in an Emergency Population Density

-

An Altruistic Personality?

Individual Differences in Motivations for Helping

The Role of Political Values

The Role of Gender

Application: Toward a More Prosocial Society

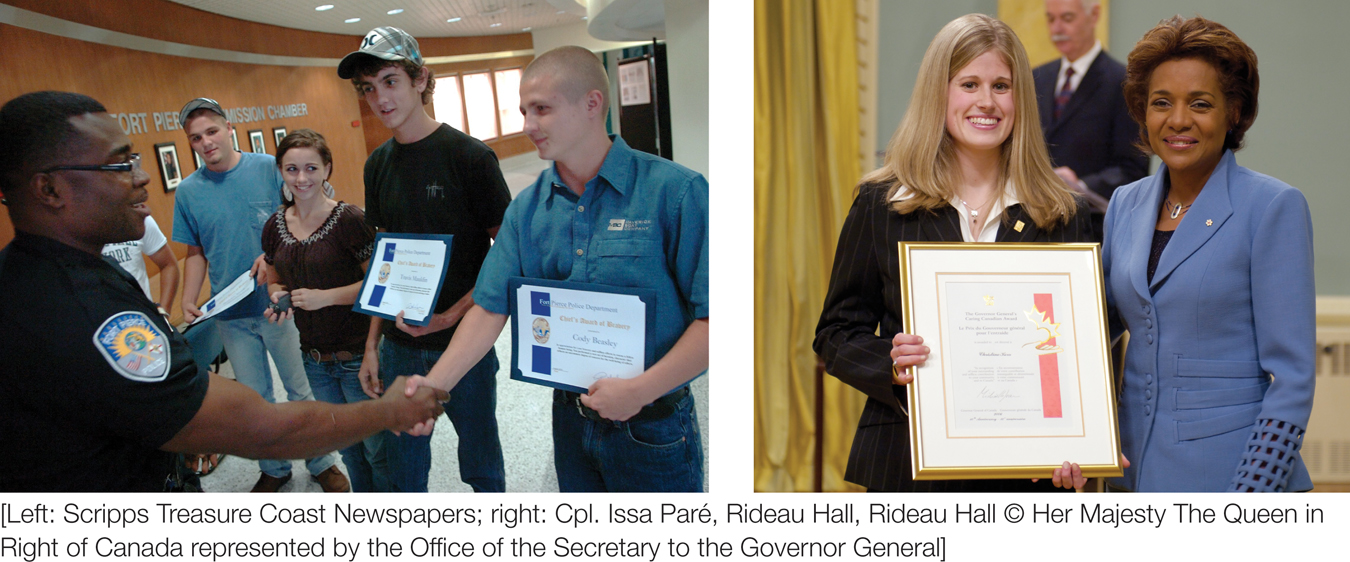

In our exploration of prejudice and aggression, we have encountered some of the darker sides of human nature. But as social animals, human beings also are drawn to help each other. Just as we can find extraordinary examples of the harm people inflict on those they do not like, we can also find examples of extraordinary acts of kindness carried out for the benefit of others. Take the example of the three men in the photo below: Cody Beasley, Travis Mauldin, and Brandon Smith. They jumped into a fast-running river to save a woman from drowning in Fort Pierce, Florida. In recognition for their bravery, they were among 83 recipients of the 2011 Carnegie Hero Fund Awards, granted to individuals who risk their own lives to save others. Also shown is Christine Kerr, who received one of Canada’s Caring Canadian Awards for her tireless dedication to volunteer work at hospitals and senior homes. Such individuals remind us that people sometimes go out of their way to help and care for others in need, even when that means making personal sacrifices or putting themselves in harm's way.

[Left: Scripps Treasure Coast Newspapers; right: Cpl. Issa Paré,Rideau Hall, Rideau Hall © Her Majesty The Queen in Right of Canada represented by the Office of the Secretary to the Governor General]

If people always helped others, we would not have much to cover in this chapter. But just as we can easily bring to mind uplifting stories of helping, we can also easily recollect instances when someone could have been saved from danger, or a social problem could have been alleviated, if people had intervened. Consider an incident in October 2009, when a 15-year-old girl was raped and beaten by several teenage boys in a dark alley outside their school’s homecoming dance (Chen, 2009). Over 20 other students were said to have watched—some even recording the horrific event on their cellphones—yet no one called the police.

Which of these events better captures human nature? Are we the devoted volunteers and brave at heart who elevate the needs of others above our own? Or are we the apathetic bystanders who look on and do nothing as great harm is carried out? We are of course both, and one of the questions that social psychology examines is why this is the case. Why do we act with compassion and courage? When do we turn our backs on others? In this chapter, we will consider the whys and whens of our prosocial tendencies.

472