14.3 Physical Attractiveness

In 2010, the CNN correspondent and blogger Jack Cafferty posed the following question “What does it mean that despite the worst recession since the Great Depression, Americans spent more than $10 billion on cosmetic procedures last year?” Although many Americans worried about health care costs, employment, and the like, they still managed to spend what money they had on tucking their tummies, enlarging their breasts, and chiseling their cheekbones—

The Importance of Physical Attractiveness

But just how important is physical attractiveness to liking someone? Is it important enough to influence who we decide to put in charge of leading our country? Todorov and colleagues (2005) showed students photographs of two of the major political candidates from each of 95 different Senate races and 600 different races for the House of Representatives in the United States. Simply by viewing these candidates’ pictures and judging their physical attractiveness, students correctly guessed the winner of each contest in 72% of the Senate and 67% of the House races.

If physical attractiveness can have such a potent influence on political decisions, just imagine how important it is for our interpersonal decisions. As you probably would guess, people who are more physically attractive are also more popular and date more frequently (Berscheid et al., 1971; Reis et al., 1980). But is physical attractiveness more important than other factors in determining whether a relationship gets off the ground? The short answer, at least in terms of the spark that gets the relationship going, is yes. For most people heading off to a blind date, the physical attractiveness of their partner is going to be the most important factor influencing whether they want to have a second date. Although as we will see later in our discussion, after we meet and get to know another person, attractiveness matters less for sustaining our interest over time.

Why Is Physical Attractiveness Important?

Physical attractiveness is important for a variety of reasons. Seen from the perspective of the reward model, it obviously contributes to sexual appeal. But sex aside, it also simply may be more pleasant to look at attractive (rather than unattractive) babies, kids, and adults. In fact, even infants gaze more at attractive adult faces (Langlois et al., 1990). Physical appearance is also typically the first attribute we come to know about a person. It takes much less time to assess someone’s looks than his or her honesty, intelligence, and other qualities; some evidence suggests it takes as little as 0.15 seconds (Zajonc, 1998). So when you meet someone, the very first impression you form will be based on his or her looks.

521

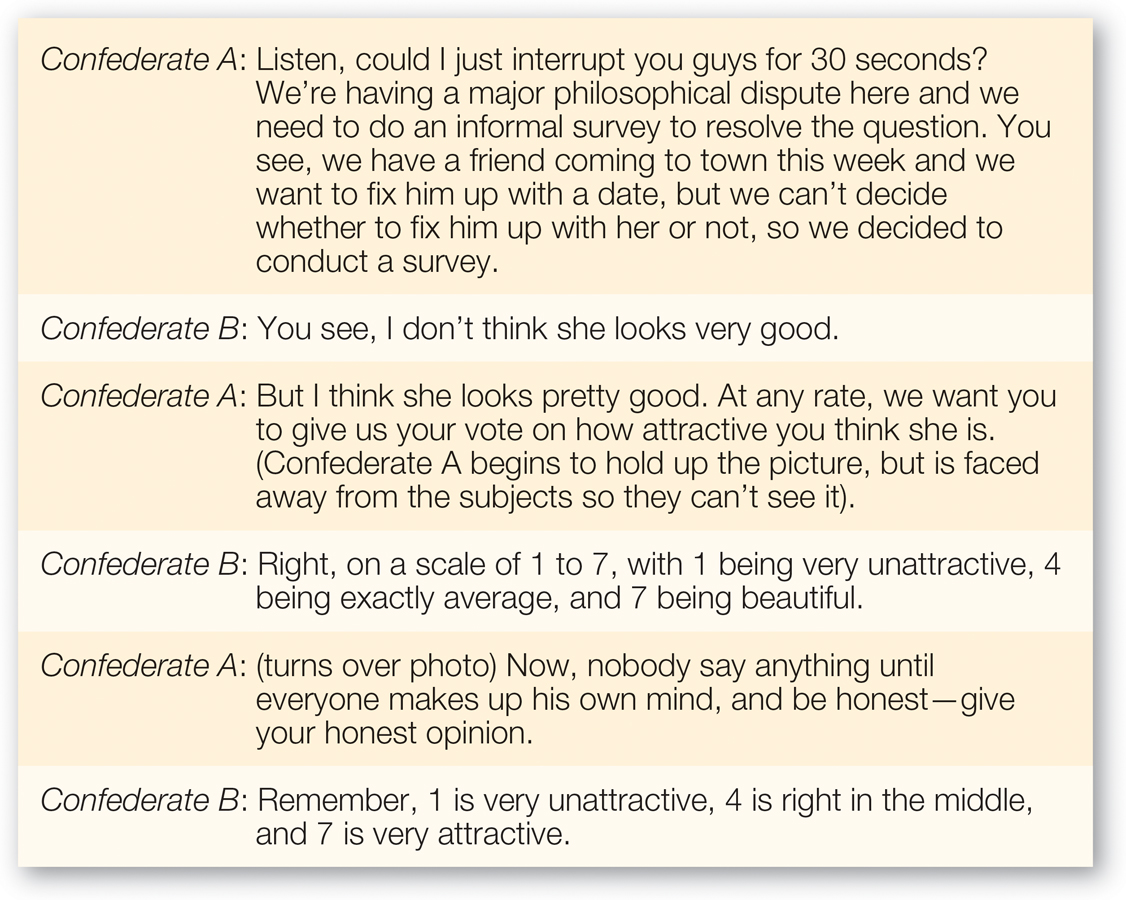

Physical attractiveness also may be important in many cultures because the hotter the person we’re with, the more we can BIRG (bask in their reflected glory). Consider a study by Sigall and Landy from 1973. As a participant in this study, you show up at the lab and find two other people in the waiting room. These two people are actually confederates. One is an average-

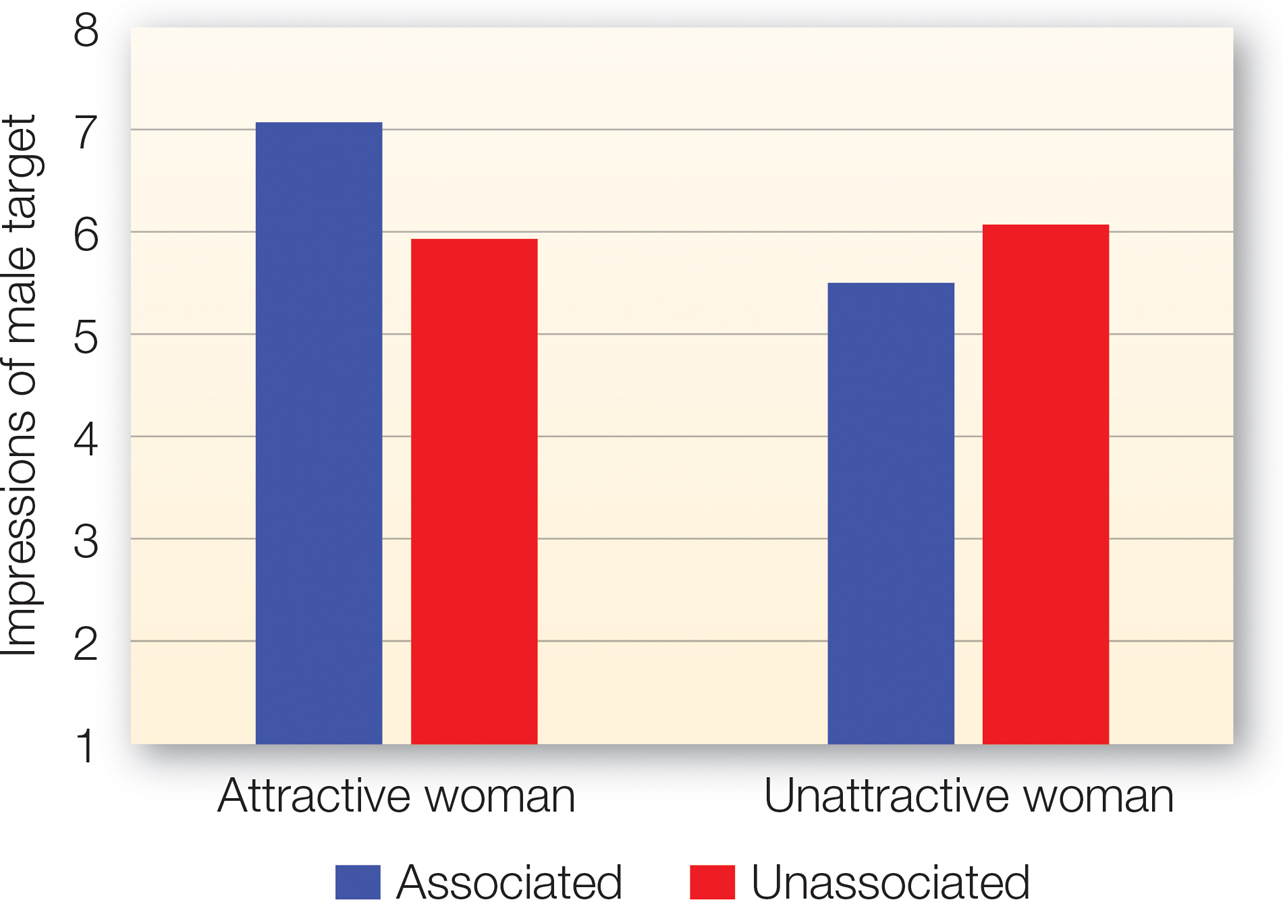

FIGURE 14.1

Basking in the Glow of Attractive Others

People’s impressions of a man were more positive when he was seen in the presence of an attractive rather than an unattractive woman, but only if he seemed to be dating her (i.e., was associated with her).

[Data source: Sigall & Landy (1973)]

What did the researchers find? As you can see in FIGURE 14.1, participants formed more positive impressions of the man when he was the boyfriend of the attractive woman (the condition labeled Associated) than when he was unassociated with the attractive woman. They formed the least positive impressions when he was the boyfriend of the unattractive woman. This shows how our impressions of people are influenced by the attractiveness of those with whom they are associated. When we date attractive people, other people see us more positively than if we dated unattractive people. What is more, people anticipate that an attractive partner can have this effect! In a second study, Sigall and Landy (1973) created a similar scenario, but asked male participants to pretend to be either the boyfriend of an attractive or unattractive confederate and then to guess how other people would rate him. Sure enough, guys thought they would be evaluated more positively when they were seen as having a relationship with an attractive woman. So part of the reason we like to be with attractive people is that we know that this will lead others to think better of us.

The Physical Attractiveness Stereotype, AKA the Halo Effect

Another reason we might care about someone’s attractiveness is that we assume it will mean that they have other positive characteristics. Despite the cultural maxims to “never judge a book by its cover” or that “beauty is only skin deep,” in Western cultures people see beautiful people (compared with those of average attractiveness) as happier, warmer, more dominant, mature, mentally healthy, and more outgoing, intelligent, sensitive, confident, and successful—

Halo effect

A tendency to assume that people with one positive attribute (e.g., who are physically attractive) also have other positive traits.

522

Lest you be tempted to think that folks simply judge more positively those people with whom they want to hook up, note that halo effects occur throughout the life span in many contexts in which sexual arousal or interest is not involved. In one alarming study, cuter premature infants were treated better in hospitals and consequently fared better than their less cute fellow preemies (Badr & Abdallah, 2001). Young children show preferences for other attractive children (Dion & Berscheid, 1974). Attractive babies get more attention from parents and staff even before leaving the hospital (Langlois et al., 1995). Halo effects continue to occur in nursery school, with attractive children being more popular (Dion, 1973). But maybe it weakens by the time children get to elementary school? No—

In some ways, though, at least with predicted success, the teachers may not have been entirely inaccurate. The benefits of physical attractiveness continue into adulthood, with implications for several positive outcomes. For example, for each point increase on a 1 (homely) to 5 (strikingly attractive) scale of attractiveness, people are likely to earn an average of about $2,000 more a year (Frieze et al., 1991; Roszell et al., 1989). Other life domains are affected as well. For instance, attractive defendants are less likely than unattractive defendants to be found guilty when accused of a crime (Efran, 1974), and when they are found guilty, they are given lighter sentences (Stewart, 1980). This bias in the legal domain is strongest in jurors who rely on their emotions and gut-

These kinds of outcomes raise important questions about whether or not there is truth to the stereotype. The answer is somewhat complex. Attractive people are generally more outgoing, popular, and socially skilled (Feingold, 1992b; Langlois et al., 2000), but they are not higher in self-

Given how favorably people react to those who are highly attractive, it’s a bit surprising that physical attractiveness is not more of a psychological boon than it actually is. Research suggests two reasons the benefits are limited. First, it turns out that people are often mistaken in their perceptions of how physically attractive other people think they are (Feingold, 1992b). So some people think they are less physically attractive than they really are. Second, no one wants to be valued only because of their looks or any other single characteristic. Highly attractive people may sometimes wonder if that’s the only reason people compliment them or care for them (Major et al., 1984).

Nevertheless, although the stereotype paints a much more positive picture than the reality, it does have some validity in the domain of social skills. For example, when researchers conduct phone interviews with attractive versus unattractive people, more attractive people are rated by interviewers (who don’t know what they look like) as more likable and socially skilled (Goldman & Lewis, 1977).

But then the next important question to ask is why? Is it because more attractive people are in fact naturally more socially skilled? Or might it have something to do with the way they have been treated throughout their lives? Take a moment and think back to our discussion in chapter 3 of self-

523

Liz (telling her boss, Jack, about her new boyfriend): He’s a doctor who doesn’t know the Heimlich maneuver. He can’t play tennis. He can’t cook. He’s as bad at sex as I am. But he has no idea!

Jack: That is the danger of being super handsome. When you are in the bubble, no one tells you the truth.

In an episode of the television show 30 Rock, Liz Lemon learns that her very attractive boyfriend is treated differently by others because of his good looks. For example, no one has ever told him that he doesn’t speak fluent French.

[NBC/Photofest]

So do beautiful people really get special treatment that then makes them more socially skilled? Snyder and colleagues (1977) set up a study to test this idea. They had a male and female participant show up (separately) to their lab and escorted them to separate cubicles such that they never saw each other. The male participant was told to interview the female through a microphone setup, and their conversation was recorded. In a critical step, before the interview, the male participant was given some information about the participant, including a photograph. The photograph either depicted a very attractive or a rather unattractive woman. Thus, the male participant thought he knew what the person he was talking to looked like, but in actuality, the photograph was of a different person. Later, independent judges who did not know what the study was about rated the female participants on various characteristics only on the basis of listening to the tape-

When the male participant thought he was talking to an attractive woman, the independent judges actually rated her more positively (e.g., friendlier and more open). Thinking that he was talking to an attractive woman, the male participant was more pleasant, and elicited pleasantness in return. This effect occurred when women conversed with men they thought were attractive or unattractive (Andersen & Bem, 1981). Indeed, meta-

Where does this stereotype come from? Partly it comes from our own motivations. We generally want to bond with attractive people, so on seeing them—

Think ABOUT

A major source of these stereotypes is the culture in which we live (Dion et al., 1972). Pretty much as soon as we pop out of the womb, we are bombarded with images, stories, and fairytales that convey a clear and simple message: Good people are good looking; bad people are ugly. Cultures probably promote this stereotype because, after all, wouldn’t life be simpler and better if the people we find physically attractive are also great in other ways, and the people we think are great were also physically attractive? Think about your favorite childhood movie or fairytale book. How were the principal characters portrayed?

Overwhelmingly the good princess is beautiful and the hero handsome, whereas the evil witch and villain are ugly. When Anakin Skywalker chooses the dark side of the force, his good looks are masked in robotic, menacing armor. From Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty, and Princess Leia (and their accompanying saviors) to stepsisters, wicked witches (with crooked noses complete with bulging warts), and Darth Vader, all of them convey pretty consistent messages.

524

Supporting this cultural media explanation, Smith and colleagues (1999) found that in popular Hollywood movies, there was a positive correlation between how physically attractive the main character was and how virtuous and successful the character was in the film. In a second study, they showed college students a film reinforcing the beautiful-

If the physical attractiveness stereotype is at least partly a product of our culture, then we should expect it to vary along cultural lines. And to a certain extent it does. People tend to associate beauty with those traits that their culture generally defines as positive and valuable. So in the United States and other Western cultures, this means seeing beautiful people as friendly, independent, and assertive. But when researchers gave Korean students pictures of attractive Koreans, they did not see them as having characteristics such as potency, which Americans value (Wheeler & Kim, 1997). Rather, Korean students judged attractive Koreans as being more honest and concerned for others, precisely the traits that are valued in that culture and less so than in the United States.

Common Denominators of Attractive Faces

“Beauty is in the eye of the beholder.” This popular saying suggests that people have very different notions of who is physically attractive. There are indeed important differences among individuals, cultures, and historical periods in assessments of what is attractive (Darwin, 1872; Landau, 1989; Newman, 2000; Wiggins et al., 1968). In recent years, teenage Twilight film fans have debated the merits of Jacob versus Edward. Magazines such as People and Maxim have yearly issues on the most attractive celebrity men and women; the rankings change substantially from year to year. People’s tastes in food, music, and clothes vary; surely their tastes in whom they find attractive also vary, both within and across cultures.

But research shows that people actually agree about who is (and isn’t) physically attractive much more than they disagree (Langlois et al., 2000; Marcus & Miller, 2003). Within and across cultures, the consensus as to who is and who is not attractive is generally strong. For example, when Latino, Asian, Black, and White men rated the attractiveness of different women in pictures, there was some variability in preferred body shape, but in general, the correlations across the groups exceeded 0.90 (Cunningham et al., 1995). This indicates strong agreement in perceptions of who is hot and who is not. What’s more, newborn infants—

The Averageness Effect

FIGURE 14.2

The Allure of “Average” Faces

If you digitally average original photos of faces, the result is a composite face. The more real faces that are used to create the composite face, the more attractive the composite face is deemed to be. Evolutionary psychologists argue that we are attracted to these “average” faces because they signal good health and thus good mating potential.

[Research from: Langlois & Roggman (1990). Photos courtesy of Dr. Marin Gruendl, www.beautycheck.de]

Beautiful faces seem to stand out from the crowd, so we might infer that attractive faces have unique features. Think again. To be attractive is actually to have quite average facial features. Researchers studying attraction have used computerimaging software to superimpose images of faces on top of each other, thus creating composite faces that represent the digital “average” of the individual faces (see FIGURE 14.2).

525

Both men and women rate these composite faces as more attractive than nearly all of the individual faces that make them up, leading to what is known as the averageness effect (Langlois & Roggman, 1990; Rubenstein et al., 2002). And the more faces that are combined to create a composite face, the more attractive that face is perceived to be. However, it’s also the case that composites of sets of faces that are attractive to begin with are viewed as more attractive than composites of nonselective samples of faces.

Averageness effect

The tendency to perceive a composite image of multiple faces that have been photographically averaged as more attractive than any individual face included in that composite.

Do these averaging effects mean that to be attractive is to have bland, ordinary looks? Not at all. These composite faces are actually quite unusual (that’s why we put “average” in quotes): They are mean composites, not modal or common faces. Their features are all proportional to one another; no nose is remarkably big or small; no cheeks are puffy or sunken. In short, nothing about these composite faces is exaggerated, underdeveloped, or odd.

Symmetry

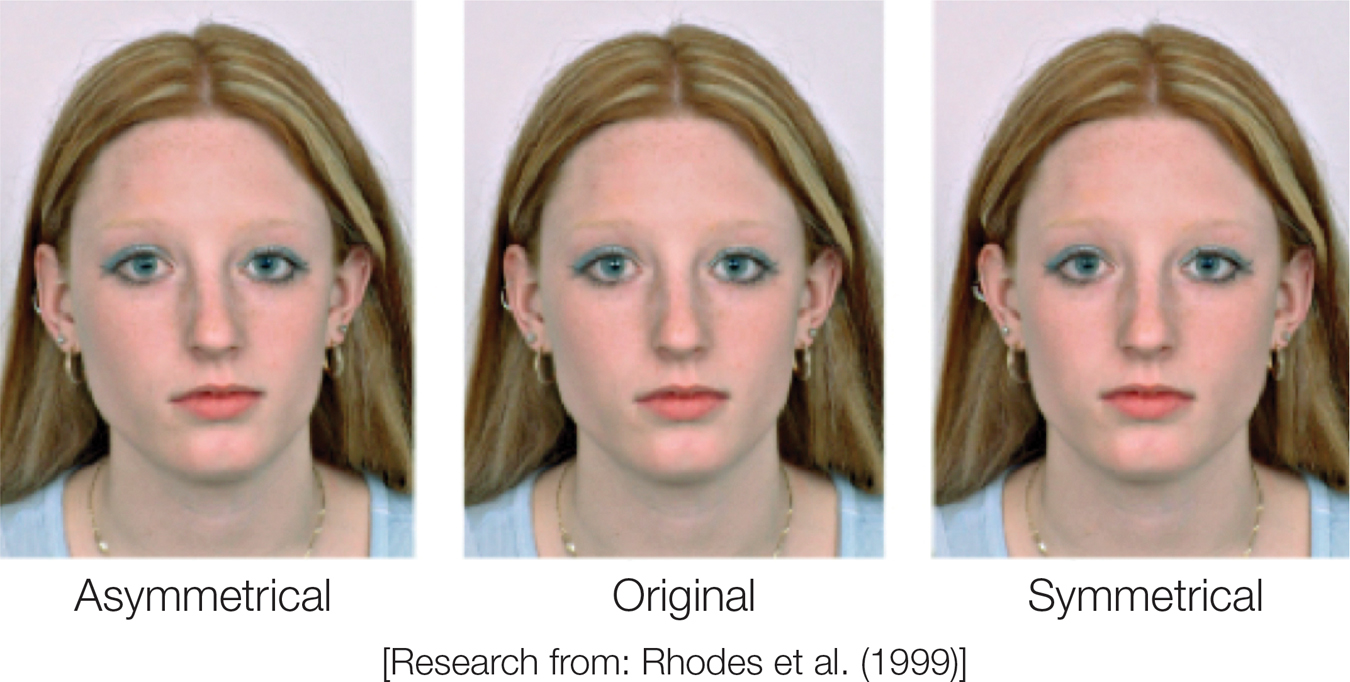

FIGURE 14.3

The Importance of Symmetry

Which of these faces do you find most attractive? People tend to rate more symmetrical faces as more attractive. Some psychologists say that this preference stems from an innate tendency to search for healthy mates.

[Research from: Rhodes et al. (1999)]

Another feature of faces that both men and women find attractive is bilateral symmetry (Thornhill & Gangestad, 1993). Symmetry occurs when the two sides of the face are mirror images of one another (FIGURE 14.3). You might think that you have a symmetrical face; after all, you probably have one eye on the right side of your face and another eye on the left. Yes, but look closer (perhaps with the help of a computer, as researchers have done) and you will find numerous asymmetries: Your eyes are slightly different in shape, size, and position on your face, your cheekbones are at slightly different angles, and, if you are like the current author, one of your nostrils has a bigger circumference than the other. All things being equal, the more symmetrical a face, the more people find it attractive.

It is interesting to note that symmetry and “averageness” each make a unique contribution to facial beauty. Composite faces made by the digital averaging process we just mentioned tend to be more symmetrical than the individual faces making them up (Rhodes, 2006). This is to be expected: When you combine faces, each face’s unique asymmetries become less noticeable. But facial symmetry is attractive in its own right, whether or not a face is “average” (Fink et al., 2006). Among symmetrical faces, those that average together the features of many individual faces are seen as the most attractive (Rhodes et al., 1999).

The preference for “average” and symmetrical faces is universal. Men and women from all over the world—

Why Are “Average,” Symmetrical Faces Attractive?

One influential answer comes from evolutionary psychology. It seems plausible that a big challenge to successful reproduction was—

But how can we tell whether or not a potential mate is in good health? One indicator may be facial features. When people are developing in utero (in the womb) before birth, their genes are normally set up to create a symmetrical face and body, with no skeletal feature badly out of proportion. Yet if they are exposed to pathogens, parasites, or viruses during development, the result can be irregular and asymmetric features of the face and body. For example, the more infectious diseases experienced by a mother during pregnancy, the more likely her infant is to show departures from perfect facial and bodily symmetry (Livshits & Kobyliansky, 1991).

526

Indeed, some research shows that men and women with more symmetrical faces are healthier than are people whose faces have odd proportions. For example, studies have found that symmetrical-

Although this evolutionary perspective on the allure of averageness and symmetry has some appeal, another explanation is that more average-

SOCIAL PSYCH out in the WORLD

Sexual Orientation and Attraction

Sexual Orientation and Attraction

I met Thea at the Portofino, a restaurant in the West Village. There was a place near it called the Bagatelle, over on University Place, and I used to go there five nights a week. I would read the Saturday Review of Literature; I would have my coffee there—

Edith Windsor provides this account of her long-

Edith Windsor (left) and her wife, Thea Spyer.

[© Neville Elder/Corbis]

Edith’s description of how her relationship with Thea unfolded reveals many of the same factors that influence heterosexual attraction. In fact, the factors that predict attraction in gay and lesbian relationships are quite similar to those that predict attraction in heterosexual relationships. People, whether they are gay, straight, or bisexual, generally are attracted to people who provide affection, are dependable, and have shared interests (Peplau & Fingerhut, 2007).

From this brief snapshot of Edith and Thea’s relationship, we can see that an initial shared interest, in dancing for example, was an important bond that fueled attraction. But they are different in many ways, consistent with some evidence that suggests less prevalence of matching on attractiveness, education, and other variables in gay than in straight relationships (Kurdek, 1995).

The overall similarity between same-

In contrast, whereas lesbians look for partners with feminine characteristics, they don’t necessarily want partners who assume what are typically feminine roles (Bailey et al., 1997). Indeed, perhaps because lesbians eschew typical gender roles, the physique they report as being most attractive is less close to the thin ideal promoted by the mass media and often preferred by heterosexual men (Swami & Tovee, 2006).

Overall, such differences are broadly consistent with the notion that women’s views on what is physically attractive about a partner of either sex are more complex and flexible than men’s views. For example, men’s sexual orientation tends to be much more fixed as being attracted either to women or to men. And men with higher sex drives are even more attracted to whichever sex is their preference. But for women, the patterns are more complex. Although heterosexual women are generally more attracted to men than to women, those with a higher sex drive are more sexually attracted to both men and women (Lippa, 2006, 2007). Yet for lesbians, a higher sex drive only predicts attraction to other women and not to men.

Edith Windsor speaks to press after winning landmark gay rights lawsuit.

[Bryan Smith/Zumapress.com/Alamy]

What happens with gay and lesbian relationships over time? In chapter 15 we will explore the challenges of maintaining close relationships over the long haul, so we won’t delve into that here. But generally, as with initial attraction, the important factors for relationships, regardless of someone’s sexual orientation, are more similar than they are different (Peplau & Fingerhut, 2007).

527

Gender Differences in What Is Attractive

Now you might wonder if there are differences in what men and women find attractive. Research into such differences covers two distinct questions. One is whether men and women differ in the kinds of physical attributes they think make a person physically attractive. The second, somewhat related question is whether men place more importance on physical attractiveness and whether women prioritize signs of social status.

We preface this section by acknowledging a few points. One is that research on this question can sometime be controversial, invoking a common nature versus nurture debate that we’ll return to later. The second is that any evidence of mean differences between men’s and women’s preferences does not preclude the possibility of a wide range of individual variation within each sex, which we will also discuss. Finally, it’s also worth acknowledging that most of the research in this area has focused on attraction to members of the opposite sex, but we will also highlight the emerging interest in studying patterns of attraction among same-

528

What Attributes Do Men and Women Find Attractive?

Although both men and women prefer “average” and symmetrical faces, heterosexual men and women differ somewhat in the physical features they find attractive in someone of the opposite sex. Here an evolutionary perspective might shed some light. Over the course of evolutionary history, men and women both were motivated to reproduce, but they faced different reproductive challenges. As a result, men and women evolved to have different, specialized preferences in their mates that favor the conception, birth, and survival of their offspring (Buss & Schmitt, 1993; Gangestad & Simpson, 2000; Geary, 2010; Trivers, 1972). Let’s look at the features that men and women each consider attractive in a potential mate, and then think back to our deep evolutionary past to see why evolution may have favored different preferences in men and women.

For Men, Signs of Fertility

The psychologist David Buss (1989) asked thousands of men and women in 37 cultures what they found attractive in a romantic partner. Across these cultures, men and women judged the attractiveness of the opposite sex on the basis of many common attributes. Both men and women gave their highest rating—

How can we account for these universal patterns in the preferences men report? An evolutionary perspective suggests that the challenge men face when attempting to reproduce is finding a mate who is fertile—put simply, capable of producing offspring. But how can men deduce a potential mate’s fertility level? One useful clue is a woman’s age. Women are not fertile until puberty, and their fertility ends after they reach menopause around age 50. As our species evolved, men who were attracted to features of women’s faces and bodies that signal that they are young (but not too young) were more likely to find a fertile mate and successfully reproduce. Those attracted to women with other features were less successful in populating the gene pool. As a result, those preferences may be built into modern men’s genetic inheritance (Buss, 2003).

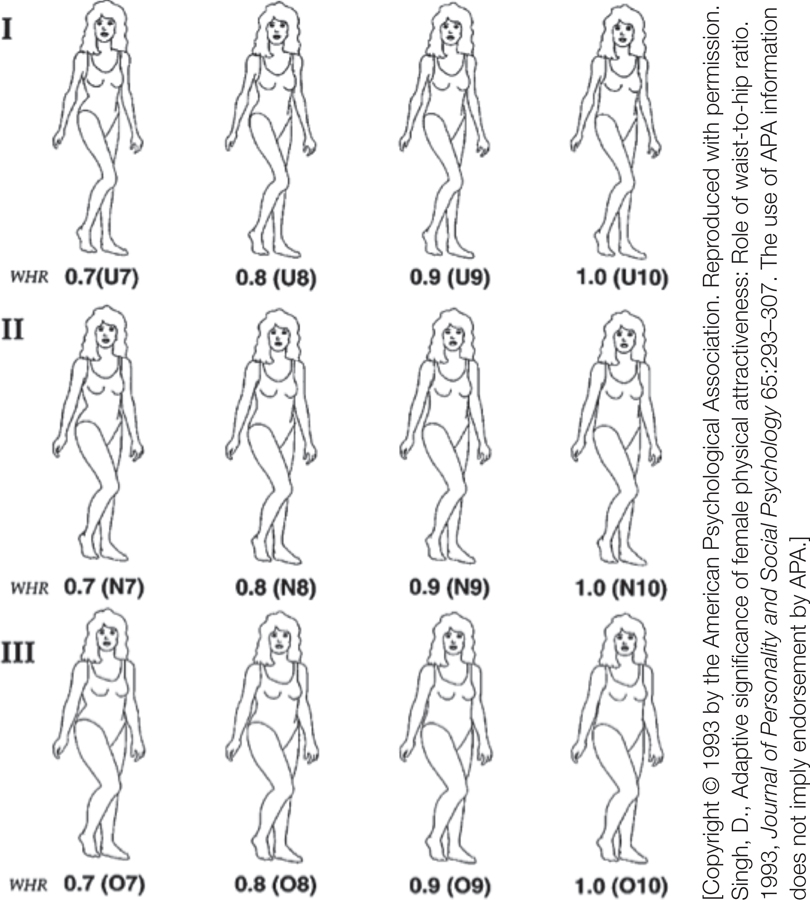

FIGURE 14.4

Waist-

When people are asked to judge which of these women is most attractive, the average preference is usually a woman with a 0.7 ratio of waist to hip.

[Copyright © 1993 by the American Psychological Association. Reproduced with permission. Singh, D., Adaptive significance of female physical attractiveness: Role of waist-

Another physical feature linked to fertility in women is waist-

Interestingly, even though men in different cultures and historical periods are attracted to varying levels of plumpness, they all agree on the appeal of a 0.7 waist-

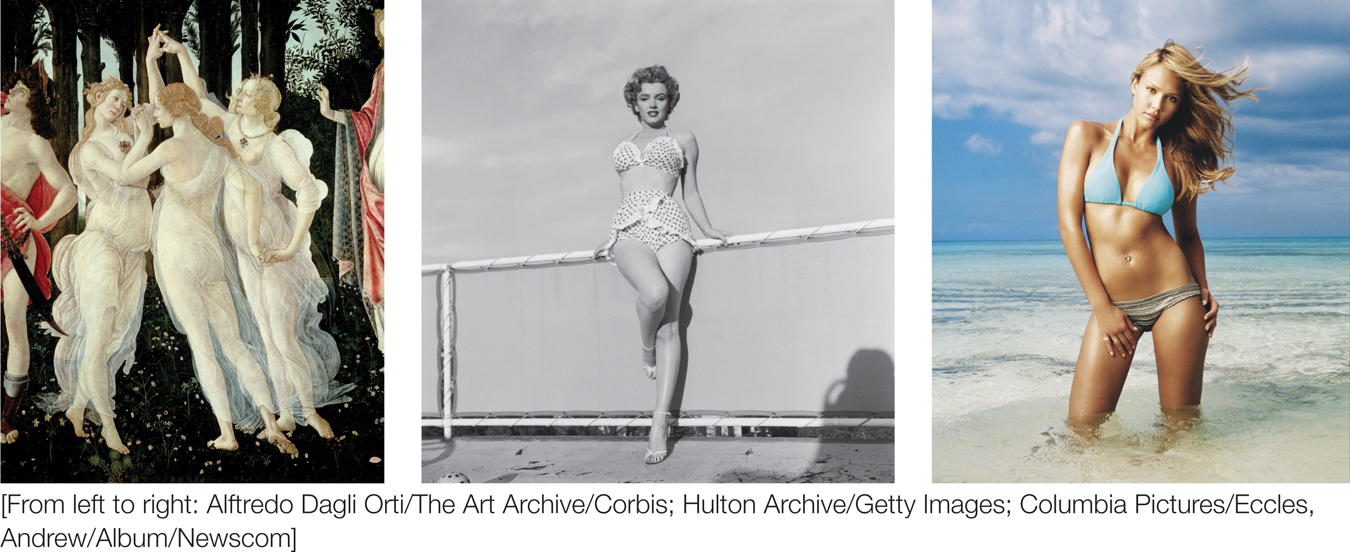

Over time, standards of attractiveness for the overall size of women’s bodies have changed, but the ideal of a 0.7 waist-

Art Archive/Corbis; Hulton Archive/Getty Images; Columbia Pictures/Eccles, Andrew/Album/Newscom]

529

A person’s waist-

For Women, Signs of Masculinity and Power

From an evolutionary perspective, women did not need to be so concerned as men with finding a youthful partner, because men’s fertility is less bound to their age. In theory, men can continue to reproduce until they die (although sperm motility does decrease, and chromosomal mutations do increase, with age). Consistent with these factors, women generally prefer their mates to be the same age as themselves or older (Buss, 1989). But consider what made it challenging for women to reproduce successfully in the primeval social environment. During the many months of pregnancy, it was more difficult for them to go out on their own to forage for food, build shelters, and fend off saber-

Given these challenges to survival and reproduction, what features do you suppose women looked for when evaluating potential mates? They might have pursued men whose physical features they associated with masculinity, virility, and social power, as well as men who could be counted on to invest resources in protecting and providing for them and their offspring. For example, women find most attractive those men who have a waist-

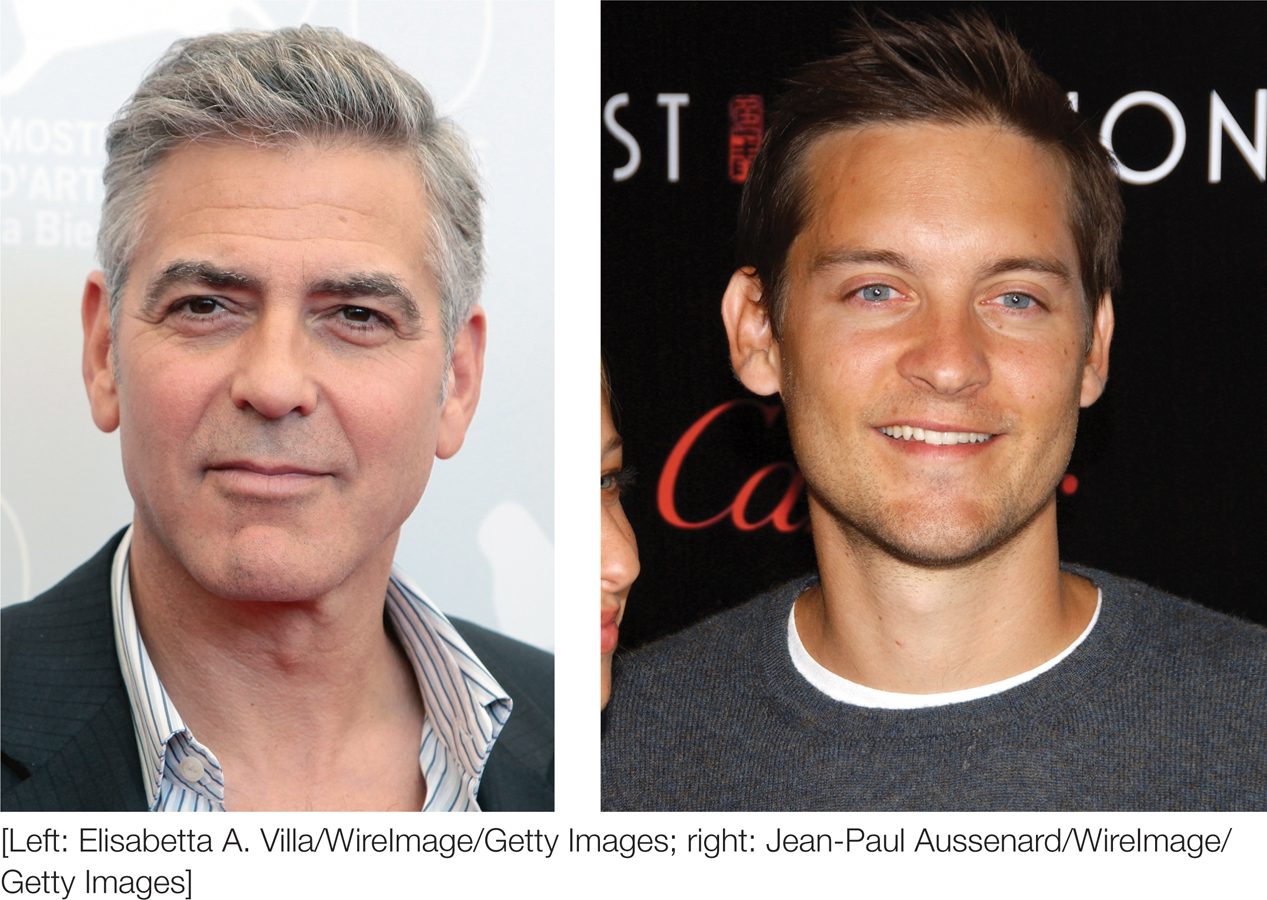

When women are at their peak fertility, they are more attracted to men with very masculine features (such as George Clooney) than to men with baby-

[Left: Elisabetta A. Villa/WireImage/Getty Images; right: Jean-

530

To demonstrate a role for women’s evolved preferences for more masculine-

In addition, during the ovulatory phase of the menstrual cycle, women seem to prefer men who have deeper, more masculine voices (Puts, 2005) and who present themselves as more assertive, confident, and dominant (Gangestad et al., 2004; Gangestad et al., 2007; Macrae et al., 2002). Thus, during the fertile phase of the menstrual cycle (as opposed to the nonfertile phase), when the probability of conception is relatively high, women might become more attracted to men who show signs of power and dominance. Presumably, over the millennia, women genetically prone to mate with more dominant men were more likely to have their genes live on in future generations. In a related study, female strippers reported earning higher tips for lap dances during high-

Men also seem to pick up on women’s fertility unconsciously and play the part of the dominant man. Men who sniffed T-

Do findings like this mean that there are fundamental, built-

531

Do Men Prefer Beauty? Do Women Prefer Status?

The evidence reviewed above largely supports an evolutionary perspective for why men and women consider different physical attributes attractive. However, another controversial question is whether men more than women care about physical attractiveness in the first place, whereas women more than men care about evidence of financial status and resources. Certainly some of the evidence fits our stereotype that men care about a woman’s beauty, whereas women care more about a man’s social status.

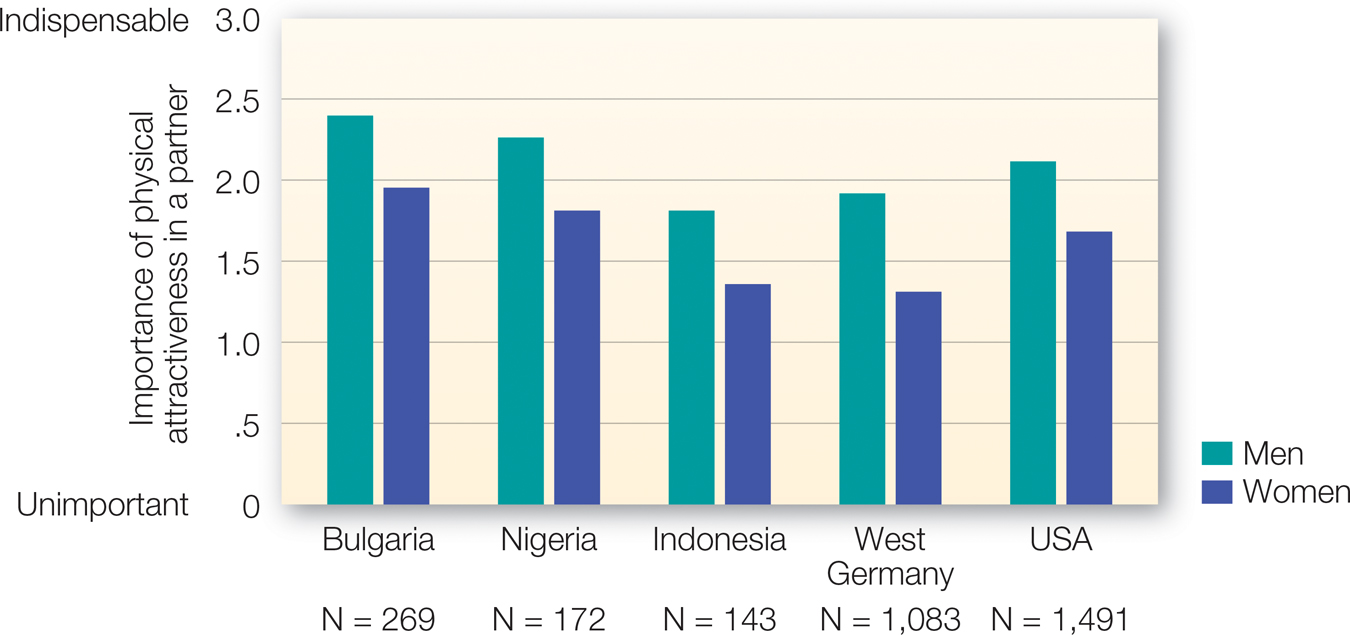

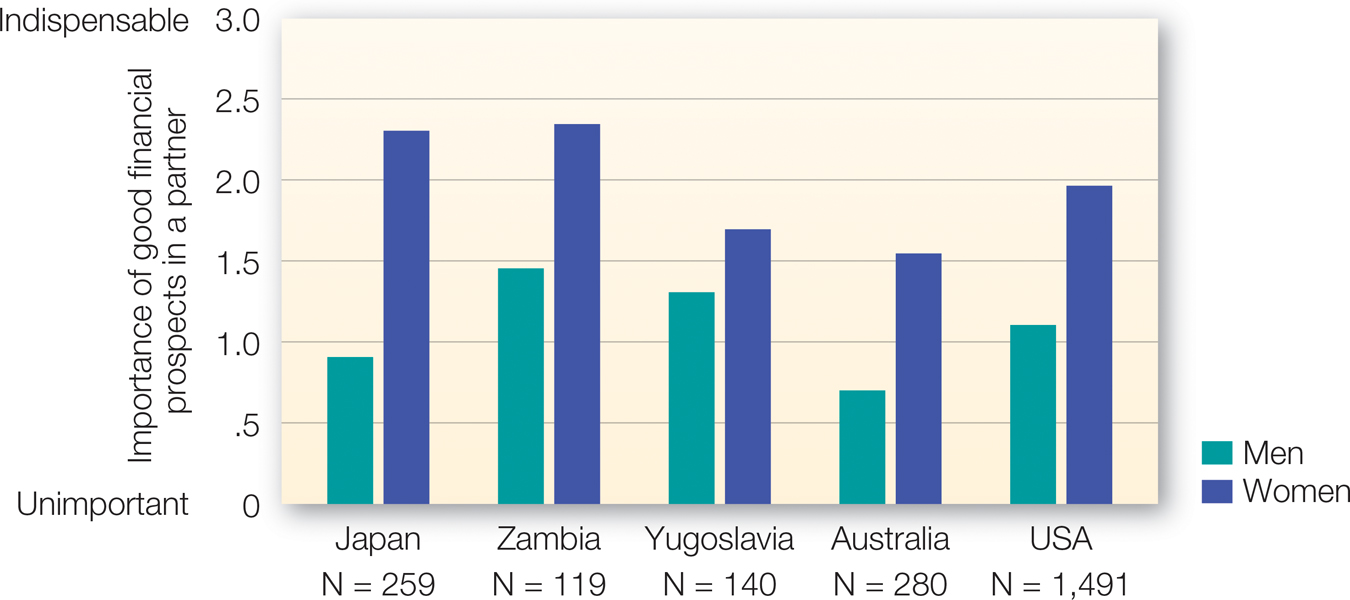

FIGURE 14.5

Gender Differences in Desire for Physically Attractive Partners

Across 37 cultures, men reported desiring physical attractiveness in a romantic partner more than women did.

[Data source: Buss & Schmitt (1993)]

For example, Buss’s (1989) initial research suggested that these gender differences exist across the 37 countries he assessed (see FIGURE 14.5) (Buss, 2008; Buss & Schmitt, 1993; Feingold, 1992a; Geary, 2010). And when given pictures and background information of potential dating partners, men were more likely than women to base their preferences on appearance, selecting the more attractive women (Feingold, 1990). In contrast, the better predictor of women’s interest in a man was his income (see FIGURE 14.6). In studies of online dating, wealthier guys get more e-

However, other researchers suggest that these results are limited. For example, note that in these studies participants are indicating only whom they think they want to go out with. Studies that examine what happens when people actually meet and interact reveal a different picture. As far back as 1966, Walster and colleagues recruited students for a “welcome dance” at the University of Minnesota. They measured the students’ personality traits, rated their physical attractiveness, and then later randomly matched men and women up for the evening. What was the best predictor of whether the students wanted to see their partners again after the dance? For men and women equally, it was the physical attractiveness of the partner.

532

FIGURE 14.6

Gender Differences in Desire for Partners With Good Financial Prospects

Across cultures, women were more likely than men to say that they look for romantic partners with financial status and resources.

[Data source: Buss & Schmitt (1993)]

Eastwick and Finkel (2008) got the same results from their speed-

The same is true for the gender difference in focus on wealth and status. Once live interaction with a potential partner occurs, the wealth and status of a potential partner are only slightly influential and equally so for both women and men (Eastwick et al., 2014). As we’ve seen throughout this textbook, we don’t always know what it is we really want. So one caveat to this discussion of physical attractiveness is that what we think we will be attracted to often is wrong once we are face to face with a real person.

To understand why women say they prefer men of higher status, when their actual behavior doesn’t follow these same trends, let’s turn to a more sociocultural account. Although it historically has been the case that men have had disproportionate if not exclusive control over material resources and economic and political power, women have gained greater access to equal opportunities in recent decades. Women’s preference for higher-

Because women in more egalitarian societies do not need to depend on their partners’ earning capacity, they tend to report placing more value on the physical attractiveness of a potential mate. If we look at the distribution of wealth in each of the countries in Buss’s (1989) study of mate preferences, we find that the more women had direct access to economic power, the more they reported that physical attractiveness mattered to them in selecting a long-

Evolution in Context

Evolutionary psychology offers a provocative perspective on what characteristics men and women initially seek in partners. However, the evolutionary perspective on mate preferences also has sparked considerable controversy as researchers debate the role of innate mechanisms and sociocultural inputs. The current evidence seems to support a role for both sets of factors.

For example, according to evolutionary psychology, both sexes are most attracted to physical features that signal the highest likelihood of good health in the other sex, but the case for this explanation as opposed to one based on familiarity is inconclusive at this point. Furthermore, although men more than women report a greater interest in physically attractive mates, whereas women report a greater interest in mates with higher status, these gender differences in stated preferences are not found in studies of actual evaluation and dating patterns and are reduced in countries with greater gender equality. Thus, sociocultural influences seem to play a role in shaping women’s changing prioritization of attractiveness and status in a mate.

533

However, evolutionary psychologists further posit that men and women are attracted to different physical attributes that helped them to solve sex-

Finally, as we noted earlier, the sex differences we’ve discussed are small compared with the similarities between men and women. In every culture, both sexes look for partners who offer warmth and loyalty, which are always rated above physical attractiveness and status (Buss, 1989; Tran et al., 2008). Everyone, it seems, desires a partner who is agreeable, loving, and kind.

The broader point is this: The study of gender differences in attraction is addressed by some researchers from an evolutionary perspective and by others from a sociocultural perspective. The truth might lie somewhat in the middle. The most important thing to keep in mind is that much like other forms of human behavior, attraction stems from an intricate web of influences derived from each person’s biology, culture, and immediate social context.

Cultural and Situational Influences on Attractiveness

Despite the cross-

Cultures vary in the kind of ornamentation people use to enhance their attractiveness.

[From left to right: © Nigel Pavitt/JAI/Corbis; Angelo Giampiccolo/Shutterstock; Dan Kitwood/Getty Images; © Blend Images/Alamy]

In addition, within cultures, standards of beauty often vary over time. For example, a study of female models appearing in women’s magazines from 1901 to 1981 found that bust-

534

Status and Access to Scarce Resources

One approach to understanding cultural variations in preferences is to note that attributes that are associated with having high status in a given culture are often seen as more attractive. Consider the current preference for tanning among Caucasian Americans. In days gone by, those lower in socioeconomic status worked outside as manual laborers. As a result, they tended to be more tanned than their financially well-

Think ABOUT

The result? Take a look at the two images of the young woman and think about which one you find more attractive. If you’re like most people, you picked the one on the right.

Most people judging Caucasian individuals now consider tanned skin more attractive. This is what Chung and colleagues (2010) discovered when they manipulated the skin tones of women on the web site hotornot.com and had people rate the attractiveness of different faces. What about for judgments of African Americans? Evidence shows that lighter skin tones are considered more attractive than darker complexions (Frisby, 2006). This may help to explain why Caucasians frequent tanning salons as well as the push for skin-

And it’s not just skin tone. Body size and weight are similarly influenced by cultural trends and values. In cultures and societies in which resources such as food are scarce, men tend to prefer heavier women, but in cultures and societies with an abundance of resources, men prefer thinner women (Anderson et al., 1992; Sobal & Stunkard, 1989). Conditions of scarcity or plenty thus influence what is desired.

Nelson and Morrison (2005) took the analysis one step further. They reasoned that not only would cultural and temporal trends in scarcity influence perceptions of attractiveness, but these influences might also operate differently depending on the situations people are in. To test this hypothesis, they asked people how much money they currently had in their pocket and later asked them to estimate the ideal body weight of an attractive opposite-

One interesting finding was that across all of Nelson and Morrison’s (2005) studies, women were not influenced by their own resources when judging the attractiveness of men. This might be because body weight is a less critical aspect of how women perceive male physical attractiveness, or because women are less influenced by situational factors when judging attractiveness.

535

Media Effects

Certainly the most ubiquitous situational influences on perceptions of attractiveness come from the mass media. Billboards, television shows, movies, magazines, and the Internet all routinely expose us to a seemingly endless parade of images of attractive people, especially women. In an interesting twist, women are less likely to be represented in some mass media such as feature films and television, but when they are, they are more likely to be physically attractive and dressed in revealing clothing (e.g., Smith et al., 2013). This leads to critical questions about what kinds of effects such exposure has both on how we view others and on how we view ourselves.

FIGURE 14.7

Angels?

When college students were asked to rate an average-

[Research from: Kenrick et al. (1989)]

Back in 1980, people had no cable or satellite television or hundreds of channels, no DVRs, no shows streaming over the Internet—

APPLICATION: Living Up to Unrealistic Ideals

|

APPLICATION: |

| Living Up to Unrealistic Ideals |

The findings just mentioned imply that when we see mass media depictions of beauty, the people we encounter in everyday life can suffer by comparison. Indeed, after men looked at Playboy centerfolds, they tended to see typical women and even their own wives as less attractive (Kenrick et al., 1989). And it is not only men’s perceptions that are affected; women’s own self-

The media’s powerful effect on women’s self-

536

The emphasis on the thin ideal is one facet of the broader tendency to objectify women, which we discussed in chapter 11 (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997). As part of the objectification of women—

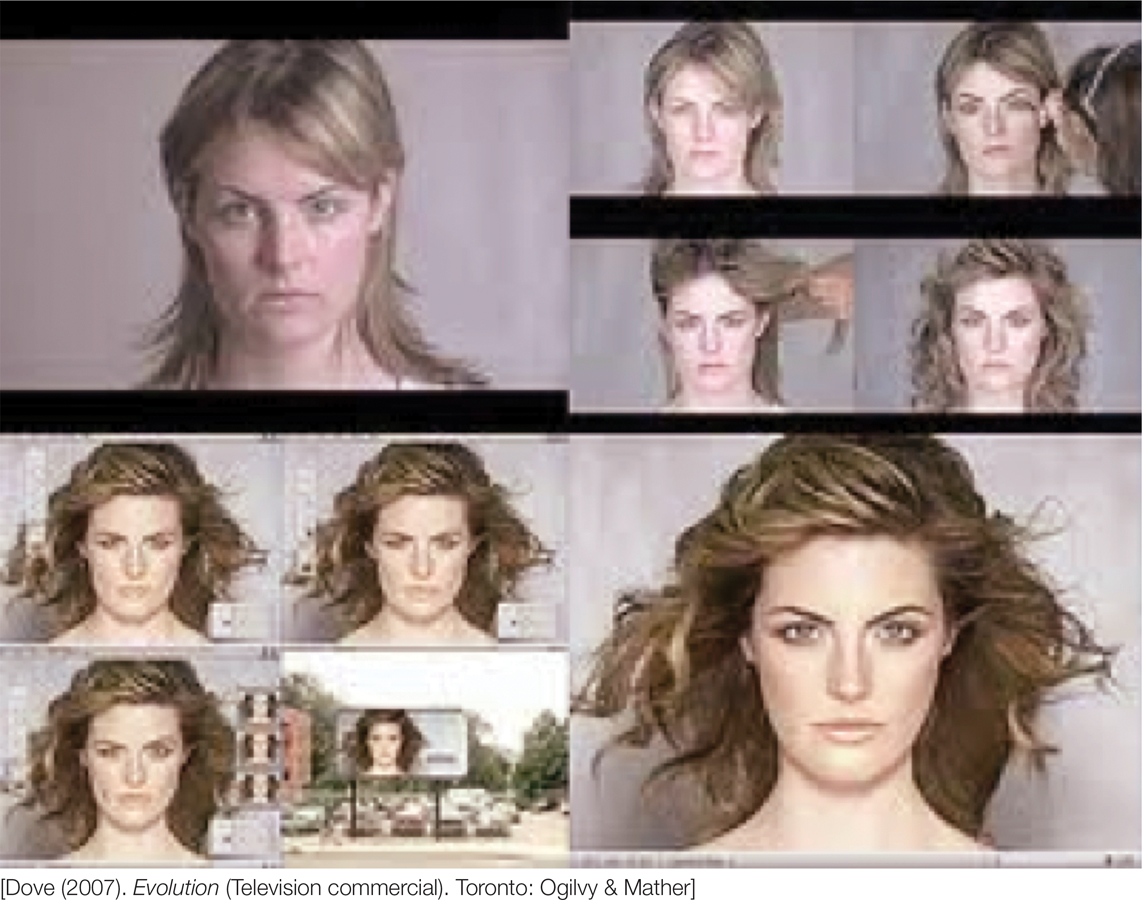

FIGURE 14.8

Evolution

Notice the progression in the model’s unrealistic attractiveness as makeup and then various computer enhancements are applied.

[Dove (2007). Evolution (Television commercial). Toronto: Ogilvy © Mather]

We refer to these standards as ridiculously unrealistic because even the people whose faces and figures appear on billboards, magazines, and movies cannot actually meet the standards of their media-

We can be thankful that some contemporary celebrities are beginning to resist these trends. Lena Dunham, Natalie Portman, Kelly Clarkson, Tyra Banks, Amy Poehler, Tina Fey, and Jennifer Lawrence are just a few of the famous women who have spoken out against public and professional pressures to present an unrealistic ideal of women’s bodies. Some organizations are putting these principles into policy. In France, Great Britain, and Norway, for example, proposals are being considered to label any image that has been digitally altered (Lohr, 2011).

537

Is Appearance Destiny?

Over 2,000 years ago, the Roman statesman Cicero (45 BC/1883) advised, “The final good and supreme duty of the wise person is to resist appearance.” If that is so, wisdom has come to our species rather slowly if at all. So far in this chapter we have dwelled on the fact that physical attractiveness is a major factor in how people evaluate potential mates. However, despite certain universal standards and the genetic basis of many of our physical features, people’s perceived attractiveness is not locked in stone at birth. Standards of physical beauty change over time and place. In addition, people often become more or less attractive as they age. Indeed, some research suggests that someone’s perceived attractiveness at age 17 does not predict the same person’s perceived attractiveness at ages 30 and 50 (Zebrowitz, 1997).

Finally, even though some physical attributes are considered universally attractive, experience with a person can also elevate his or her beauty. Research clearly shows that people who are viewed positively or as familiar and who are liked or loved are all rated by perceivers to be more physically attractive (e.g., Gross & Crofton, 1977; Lewandowski et al., 2007; Price & Vandenberg, 1979). And the happier a couple is with their relationship, the more physically attractive they view each other as being (Murray & Holmes, 1997).

|

Physical Attractiveness |

|

Research reveals the importance of physical attractiveness, what people find physically attractive (and why), and the consequences for relationships. |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The importance of physical attractiveness Sexual and aesthetic appeal do predict liking. Association with attractive people can bolster self- Attractive people are stereotyped to have positive traits. |

Common denominators of attractive faces Composite and symmetrical faces are rated as more attractive, perhaps as a reflection of good health or because they seem familiar. |

Gender differences in what is attractive Men universally prefer a waist- At times of peak fertility, women seem to be more attracted to more masculine faces. Men report an ideal preference for attractiveness and women an ideal preference for social and financial status. In actual relationships, men and women are equally influenced by physical attractiveness and, to a lesser extent, partner status. Women’s stated preference for higher- Both men and women rank warmth and loyalty above all other factors. |

Cultural and situational factors Standards of beauty vary across cultures and over time. Scarcity and status influence trends. Mass media have been influential in creating impossible standards of beauty that may be hurtful to self- |

Is appearance destiny? Attractiveness can change across time and place. People can control their perceived attractiveness by being positive in expression and behavior. |

538