15.6 Long-term Relationships: Understanding Those That Dissolve and Those That Thrive

First let me state to you, Alfred, and to you, Patricia, that of the 200 marriages that I have performed, all but seven have failed. So the odds are not good. We don’t like to admit it, especially at the wedding ceremony, but it’s in the back of all our minds, isn’t it? How long will it last?

—Reverend Dupas (played by Donald Sutherland), in the movie Little Murders (Brodsky et al., 1971)

Celebrity couple Gwyneth Paltrow and Chris Martin announced their plan to divorce in 2014, a fate shared by approximately 50% of American marriages.

[Kevin Mazur/Getty Images for J/PHaitian Relief Organization]

Most estimates put the divorce rate in the United States at nearly 50%, meaning that almost half of all marriages don’t last “so long as you both shall live.” Depending on the source, this divorce rate is at, or at least near, the highest of most industrialized countries. Moreover, the estimate climbs to between 65% and 75% for second marriages and even higher for third marriages.

These figures are troubling, given that stable and fulfilling marriages are associated with better physical and mental health, better educational attainment, and economic achievement for both parents and children (Kiecolt-

580

Given the benefits of a good long-

Not a good sign: According to John Gottman’s research, eye-

[cstar55/E+Getty Images]

On the basis of observations of thousands of couples discussing sources of marital conflict, Gottman pinpointed a cascading process in which criticism (telling the partner his or her faults) by one partner leads to contempt (making sarcastic comments about the partner or rolling one’s eyes), which in turn leads to defensiveness (denying responsibility), which in turn leads to stonewalling (withdrawing or avoiding).

Gottman refers to these stages as the four horsemen of the (relational) apocalypse, because their appearance strongly foreshadows the dissolution of a relationship. Fortunately, as we will see, there are ways of overcoming this cycle of relational doom.

Gottman (1993) found that by looking at patterns of negative affect and contempt when discussing problems, he could predict which couples were likely to divorce in the first few years and which were more likely to divorce after about 14 years. A high level of negativity—

Should I Stay or Should I Go?

Think ABOUT

Think about one of the romantic relationships that you’ve had. Did you stick with it? Or did you head for the door? Why? Your initial response may be that it depended on how satisfied you were with the relationship. The less satisfied you were, the more likely you were to get out the dump truck. But this is likely only part of the story.

Recall that the social exchange model takes an economic perspective on relationships and posits that rewards, costs, and comparison level determine relationship satisfaction. Caryl Rusbult’s (1983) interdependence theory expanded on the social exchange model to understand relationship commitment. This theory proposes that satisfaction is only one of three critical factors that determine commitment to a particular relationship. Check out FIGURE 15.14. In addition to the person’s satisfaction with the relationship (which is influenced by rewards, costs, and comparison levels), Rusbult argues that we also need to consider the person’s investments in the relationship and the alternatives that the person sees out there in the field.

Interdependence theory

The idea that satisfaction, investments, and perceived alternatives are critical in determining commitment to a particular relationship.

FIGURE 15.14

Rusbult’s Interdependence Model

According to Rusbult, the commitment to a relationship is influenced not just by a person’s satisfaction with that relationship, but also by how much the person has invested and the quality of the alternatives the person thinks are elsewhere. When satisfaction and investment are high, and the quality of alternatives is low, stronger commitment and relationship maintenance generally follow.

[Research from: Rusbult (1983)]

581

Part of what keeps people committed to a relationship is the investment of time and resources they have put into building a life together. In the short term, spending even a few weeks dating someone, getting to know him and his friends, giving up other activities to be with him, all contribute to a sense of having invested in the relationship. The greater the sense of investment, the harder it is to give up and walk away on what you have begun to build together. Once you have held an extravagant wedding ceremony, combined financial accounts, signed your names on a mortgage, raised children, and melded your social networks and sense of family, it’s not exactly easy to disentangle two individual lives from the partnership that has developed. Costs might need to really start outweighing not just current benefits but the sum total of what you’ve put in to the relationship. For example, among same-

In addition to satisfaction and investment, the third factor that can contribute to your overall commitment is an assessment of the options available to you. When you apply the comparison level for alternatives, you are assessing whether you have other, better options than your current relationship. People may remain committed to or dependent on a dysfunctional or devolving relationship if they cannot imagine a better alternative. Current outcomes might seem bad, but perhaps being alone seems even worse. When your comparison level for alternatives is low, your commitment remains high. This relationship is consistent for both men and women (Bui et al., 1996; Le & Agnew, 2003). In light of the comparison level for alternatives, it’s not too surprising that over a third of marriages that end in divorce involve at least one partner having an extramarital affair (South & Lloyd, 1995). Many people don’t think about leaving their current relationship until they have a glimpse of what life could be like in another. Of course, once a partner has been unfaithful, the likelihood of divorce increases (Previti & Amato, 2004).

Comparison level for alternatives

The perceived quality of alternatives to the current relationship.

One of the interesting aspects of the interdependence theory of relationship commitment is that it highlights how an individual can be relatively satisfied in a relationship and invest a great deal in it but still decide to leave if he or she suspects there are better alternatives. For example, perhaps Brad Pitt was satisfied with Jennifer Aniston but left because he thought Angelina Jolie was that much more appealing. Conversely, some individuals might decide to stay in a relationship, not because they are especially satisfied, but because they don’t see any other better options out there. This helps to explain why people will sometimes stay in relationships that to any outside observer look rather bleak and may even involve abuse. Research has supported this explanation. For example, a study by Rusbult (1983) that followed couples over a seven-

582

The decision to stick with a relationship also is influenced by how well the relationship meets our psychological needs. As we discussed in chapter 6, self-

Sometimes the decision to break up, though obviously destructive to the relationship, is ultimately good for one or both of the individuals. We all know people—

The longitudinal aspect of this study is powerful because it reveals how, in this case, attachment anxiety and need satisfaction influence behavior over time. However, all study designs have their weaknesses, and here the weakness is that we can’t be sure that attachment anxiety was really the important factor. This is because it was just measured, not manipulated. Some other variable associated with attachment anxiety might be influencing relationship commitment.

To address this issue, in a second study, Slotter and Finkel (2009) took advantage of the strengths of the experimental method, reasoning that anyone can feel more or less secure in their relationships at various times. Think about those times when you’ve eagerly monitored your partner for signs, such as smiling or holding your hand, that he or she is in fact really into the relationship, but at other times you wonder if perhaps he or she has tired of you. Because most people have a mix of good and bad memories, the researchers manipulated whether participants brought to mind ideas related to relational security or insecurity. They first measured how much participants regarded the relationship as meeting psychological needs, and then randomly assigned participants to unscramble various words to form a sentence. The list contained either words such as was, reliable, the, mother or words such as was, unreliable, the, mother. Thus, participants were making sentences that got them thinking about either relational security (e.g., the mother was reliable) or insecurity (e.g., the mother was unreliable). The results were similar to those in Study 1. When participants did not see the relationship as meeting their psychological needs and were primed with insecurity, they expressed greater levels of commitment to the relationship. But when primed with security, they expressed less commitment to the relationship when it was not meeting their needs.

583

In short, more securely attached people are more likely to bolt from a relationship that they do not see as sufficiently fulfilling their psychological needs. Without a strong sense of commitment, such individuals are unlikely to engage in behaviors that help to maintain the relationship, such as making sacrifices for the relationship and responding to betrayals or problems with forgiveness (Finkel et al., 2002).

APPLICATION: One Day at a Time: Dealing With Daily Hassles

|

APPLICATION: |

| One Day at a Time: Dealing With Daily Hassles |

Infidelity and emotional and physical abuse are common and rather dramatic causes of relationship problems and breakups. But all long-

Maintaining a satisfying long-

Another factor is how relationship partners interpret the variability—

How do people separate their overall evaluation of the relationship from the immediate events that they are experiencing? It depends in large part on the attributions that they make for the recent event. People who are in happier relationships tend to attribute their partner’s irritating actions to external factors. So if the partner fails to call to let them know that he or she will be late, the happily married person tends to attribute that faux pas to a busy time at work rather than being inconsiderate. This helps to protect the relationship and maintain a measure of positivity. In contrast, spouses who make internal attributions and blame the other person tend to have unhappier marriages (Bradbury & Fincham, 1990). The moral here is, Don’t sweat the small stuff.

Obviously, letting daily hassles roll off your back will make for a happier relationship both in the short run and over time (McNulty et al., 2008). But what if your partner really is being inconsiderate? The tricky part of relationships is that some of the small stuff really is small, but some of it can be signs of something larger. (Remember those eye rolls that can signal contempt?) Couples who ignore the big issues, or issues for which they are unable to come up with external attributions, are likely to report lower marital satisfaction as time goes by. So the key, then, is to pick your battles wisely: to recognize what are the little things you can let slide and attribute to external factors, and what are the bigger issues that you need to address more candidly. Indeed, research shows that when the problem is not a major one that will fester, avoiding conflict over it can be the best strategy (Cahn, 1992; Canary et al., 1995).

584

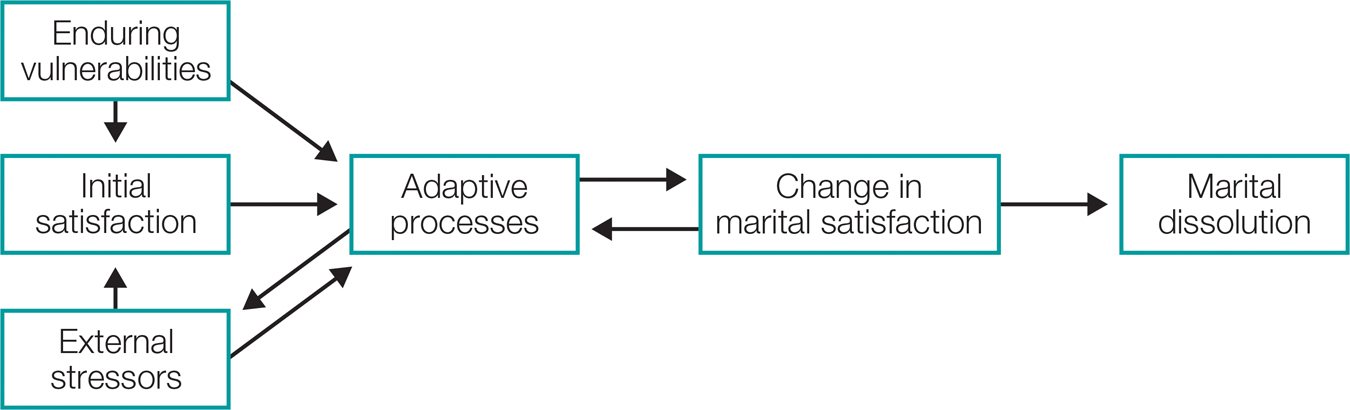

FIGURE 15.15

Vulnerability Stress Adaptation Model

When does a relationship dissolve? Karney and colleagues’ vulnerability stress adaptation model of relationships proposes that the answer depends on how situational stressors interact with personality traits (or vulnerabilities ) to create unproductive processes. For example, being insecure and facing stress at work could lead a person to have more maladaptive thoughts about the relationship, which can contribute to dissolution.

[Research from: Karney et al. (1995)]

As you probably know from your own experience, distinguishing little and big issues can be challenging to pull off. Often it’s easier early in the relationship, when the novelty of the person casts a more positive glow on your interactions. But as times goes by, and the hassles of life crash the party, the partners’ personality characteristics and elements of their situation can push them toward maladaptive relationship cognitions. Benjamin Karney and colleagues’ (e.g., Karney & Bradbury, 1995) vulnerability stress adaption model of relationships provides a framework with which to understand how these challenges operate. The model in FIGURE 15.15 highlights two key factors that contribute to marital dissolution. First, in any intimate relationship some people bring with them vulnerabilities (e.g., personality traits) that dispose them to have less adaptive relationship cognitions. For example, people with low self-

But dealing with enduring vulnerabilities is only part of the issue. The second key factor is external situations that put more strain on the relationship. Imagine a person in sales who faces added work pressure as the economy plummets. As a result, she spends less time at home and is worn out when she does. So she shows less affection to her boyfriend and shares in fewer mutual activities. This adds stress directly to the relationship (Neff & Karney, 2004). But this stress can also affect the relationship indirectly. Recall from chapter 5 our discussion of ego depletion. This work taught us that our ability to regulate our behavior effectively toward desired goals is undermined when we are burdened with additional demands. It requires effort to engage in adaptive relationship cognitions, to realize for example, that your partner’s not complimenting you on your surprise cleanup of the house is the product of her work distractions and not her general lack of appreciation for you. Thus, when people encounter outside stress, it can consume the cognitive resources that they would otherwise use to support their relationships. For example, satisfied couples make allowances for a partner’s bad behavior and attribute it to external causes (Bradbury & Fincham, 1992), but when under stress, they shift to a more maladaptive attributional pattern (Neff & Karney, 2009).

585

And in the Red Corner: Managing Conflict

As if day-

All couples, however, will need to confront conflict at least some of the time. Indeed, it is healthy for the relationship for this to happen (Cahn, 1992; Cloven & Roloff, 1991; Rusbult, 1987). Disagreements will happen: There is no perfect partner who will agree with you about everything. Your expectations have to be realistic. Your partner may prefer different types of movies to see or music to listen to. You may disagree about who should take out the garbage, cook, do the laundry. Partners may have different preferences in terms of sexual activity. They may have different ideas about where to vacation or how to spend disposable income. Issues may arise regarding whether to have children and when, and if so, how to raise them. Resolving such disagreements involves communication and compromise. So what separates happy from distressed couples in how they with deal with such problems?

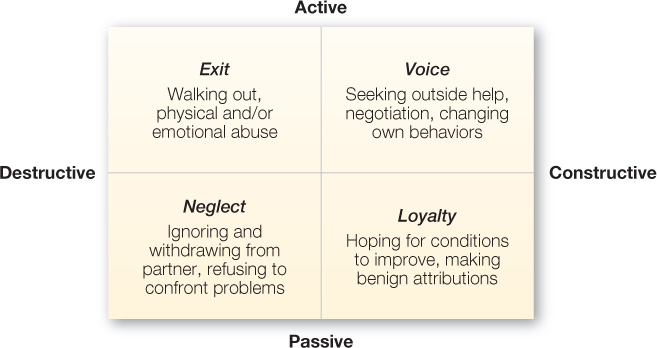

FIGURE 15.16

Managing Conflict: The EVLN Model

Carol Rusbult’s work on managing conflict suggests that people can do so in active or passive and constructive or destructive ways. When we combine these two dimensions, we get four kinds of responses. Your best bet if you want to nurture your relationship: Try for the voice response, which is both active and constructive!

[Research from: Rusbult et al. (1982)]

Let’s take a closer look at some of the strategies people apply when conflicts come up. We can divide them along two dimensions (Rusbult et al., 1982). Along one dimension are responses ranging from active (e.g., barraging your partner with a list of reasons that what she did was wrong) to passive (e.g., sitting quietly and seething). Along the other dimension are responses ranging from constructive (e.g., sticking by your partner and hoping things will get better) to destructive (e.g., smashing the headlights out of your partner’s new car). When we cross these two dimensions with one another (see FIGURE 15.16), we see four different types of responses.

An exit response is active but destructive to the relationship. It involves separating or threatening to leave. An example of an exit response is “I told him I couldn’t take it anymore and it was over.” A voice response is similarly active but more constructive to the relationship. It involves discussing problems, seeking solutions and help, and attempting to change. For example, with a voice response, one might say, “We talked things over and worked things out.”

But not all responses take this active approach. Partners also can respond constructively but in a more passive way. Loyalty entails hoping for improvement, supporting a partner, sticking with it, and continuing to wear relationship symbols (such as rings): “I just waited to see if things would get better.” Although loyalty is generally considered a constructive response, it can be relatively ineffective, because it may be difficult for the other partner to notice and pick up on it (Drigotas et al., 1995). And if it does go unnoticed, it is not likely to help the relationship. Finally, a person may respond both passively and destructively with neglect, letting things fall apart, and ignoring a partner or drifting away from him or her: “Mostly my response was silence to anything he said.”

586

In asking people to recall a time when they had conflicts with their partner, Rusbult’s work finds that people in satisfied and committed relationships are more likely to use constructive responses such as voice and loyalty and less likely to turn to exit and neglect responses. So it’s not that good relationships don’t involve conflict but that they deal with it more positively, primarily with voice. People in good relationships are also more likely to accommodate a partner’s initially destructive response and respond constructively to it. So what do you do when your partner comes home from a long day, you’re excitedly telling him about your day, and he responds, “Just be quiet for a moment”? Whereas some people’s first response might be a similarly caustic and disparaging comment—

Another characteristic that facilitates more productive accommodation is taking the partner’s perspective. The more we can put ourselves in our partner’s shoes and see that perhaps a frustrating day at work led her to act that way, the better off our relationship is. Indeed, among both dating and married couples, preexisting tendencies for perspective taking and being induced to take the other’s perspective led to more positive emotional reactions and relationship-

Given that voice is the best response to serious or recurring relationship problems, it may be worth considering two primary reasons that it isn’t always how people respond. The first reason is that people often avoid conflict. They are afraid to bring up issues because they don’t “want to get into it” or have it “blow up.” So instead, they often complain to friends or relatives about what’s bothering them. This approach doesn’t give the other person a chance to step up and help make things better.

The second reason is that people often approach communicating about problems in the wrong way. Canary and colleagues (Canary & Cupach, 1988; Canary & Spitzberg, 1987) proposed that there are three strategies for conflict management: integrative strategies, distributive strategies, and avoidant strategies. As we noted earlier, avoidance can be best when the problem is relatively minor and we can mentally or behaviorally adjust to it. But if it’s a problem that must be addressed through some kind of compromise, then it’s a matter of how you do it.

An integrative strategy works best. You present the problem as a challenge to shared relational goals, as our problem, something we have to solve together. You raise your concern while seeking areas of agreement, express trust and positive regard, and negotiate alternative solutions through frank and positive discussions (Masuda & Duck, 2002). Recently Eli Finkel and colleagues (2013) showed that having couples take about 20 minutes to learn to think about resolving their disagreements in an integrative way improved marital satisfaction over a two-

In contrast, a distributive strategy is competitive, emphasizes individual goals, assigns blame, and often devolves into insults and hostility (Masuda & Duck, 2002): “I have a problem with your behavior. You need to change. My needs are not being met.” If you are defensive or insecure, or if you’ve “bitten your lip” for a long time and so are very frustrated, you are more likely to express your concerns in this distributive, accusatory fashion—

587

Booster Shots: Keeping the Relationship and Passion Alive

Managing conflicts and dealing productively with day-

Love as Flow

Security is wonderful, and the longer one is with a partner, the more familiar and comfortable a relationship is likely to feel. But a big issue in long-

If the challenges of satisfying your partner are more than you can handle and it is too difficult to keep your partner satisfied, you experience stress, and the relationship is likely to flame out early. However, if you’re in a relationship for a long time, you learn a lot about your partner. It becomes easier to know his or her likes and dislikes, to predict his or her actions, and so forth. The challenge tends to diminish over time even as your skills increase. But if the challenges become insufficient, flow is impeded, and boredom is likely to set in. This suggests that the prospects for long-

The prospect of change can be scary, though: The same old same old is comfortable and easy. And it’s a hassle to support your partner’s personal growth; it’s easier to maintain the status quo. Thus people are often tempted to squelch their partner’s efforts to grow and change. For example, some years back, one of your author’s wives, who had been working part time ever since they got married and had children, raised the idea of going back to school to get a PhD. He instantly realized this would mean loss of income and years of stress for her (and him); pushing through the challenges of advanced education, such as writer’s block; and so on. But his wife was bored with her work and needed this growth experience to meet her professional goals, and so he supported it. By supporting her growth, he gained a more stimulating, fulfilled partner, which served both his wife and their relationship well. Research supports this example. One partner’s helping the other achieve his or her own self-

588

Emotional Support

Being a responsive partner is not limited to supporting big-

Keeping the Home Fires Burning

Of course, a big part of nourishing a relationship is keeping passion alive. This can be tough. One of the chief complaints about long-

SOCIAL PSYCH at the MOVIES

Husbands and Wives

Husbands and Wives

Although many feature Alms focus on romantic relationships, the emphasis usually is on the early stages and rarely on the challenges of maintaining a satisfying marriage over the long haul. One exception is the Woody Allen film Husbands and Wives (Greenhut et al., 1992), which focuses, almost in documentary style, on two long-

As the film unfolds we learn why. These reasons, and the dynamics they lead to, reflect many of the ideas discussed throughout this chapter. Jack becomes dissatisfied with his and Sally’s sexual relationship and also feels judged and stifled by Judy. He senses a lack of stimulation and growth. They have intimacy and commitment but little passion. He begins engaging the services of a high-

Once Jack and Sally break up, Jack is better able to grow in his relationship with Sam. He starts eating right and exercising and can enjoy sports events and movies, activities that would have met with Sally’s disapproval. Judy sets Sally up with Michael (Liam Neeson), who is handsome, charming, romantic, and younger. But Sally can’t really give him a chance, partly because of the anger she still feels toward Jack. But it’s also because she misses the deep sense of psychological security she derived from her marriage and her sense of the investment she had put into it. Eventually, Jack finds out that Sally has begun dating, which makes him jealous. He starts seeing the younger and less sophisticated Sam through the eyes of his friends as an embarrassment that is hurting his stature and self-

Gabe and Judy seem solid as the film opens, but Judy becomes particularly upset when Sally and Jack announce their divorce. It strikes a nerve. Judy begins to reexamine whether she is happy in her marriage, and as she does, we start to see its shortcomings. Meanwhile, Gabe, a professor of English and an accomplished fiction writer, becomes attracted to and Interested in one of his much younger students, Rainer (Juliette Lewis). She is a big fan of his work and reciprocates the interest.

It turns out that Judy doesn’t feel valued or emotionally supported by Gabe. He dismisses her feedback on his new novel while being intrigued by Rainer’s feedback about it. Judy becomes attracted to Michael even though she sets him up with Sally. She shows Michael poems she has written. When Gabe finds out, he asks her why she didn’t show him the poems. She says that she wanted some supportive feedback, not the kind of objective critique that Gabe would have offered. Gabe likes the security he gets from his marriage, but a lot of his self-

After Sally dumps Michael to return to Jack, Judy, seeing a better alternative, ends her marriage and starts seeing Michael. Eventually Judy and Michael marry. Toward the film’s conclusion, Gabe rejects a romantic advance from the much younger Rainer, sensing that it would not work out in the long run, and expresses regret that he took Judy for granted. In an interesting twist, soon after this movie came out, Woody Allen, then 56, became committed to a much younger woman, Soon-

During the film, we learn about Gabe’s new novel, which discusses Nap and Pepkin, men who live on the same floor of an apartment building. Summing up a major theme of the movie, Gabe writes: “Pepkin married and raised a family. He led a warm domestic life, placid but dull. Nap was a swinger. He eschewed nuptial ties and bedded five different women a week…. Pepkin, from the calm of his fidelity, envied Nap; Nap, lonely beyond belief, envied Pepkin.” Husbands and Wives thus offers insights into a variety of relationship processes, including how people try to balance the desires for security and for stimulation and growth.

589

One of the aspects of approach goals that may facilitate desire is that they lead people to more arousing and exciting activities. Such activities can help to restore the stimulation and novelty of a relationship that typically wanes over time (Aron et al., 2000). There are a number of reasons why novel and arousing activities might help to do this. As Aron and colleagues point out, such activities are often intrinsically enjoyable. When they are shared, this enjoyment becomes associated with the relationship. Such activities can also generally increase positive mood, which in turn, can be a booster shot making life, and perhaps the relationship, seem more meaningful (King et al., 2006).

590

Furthermore, as the two factor theory of love and related research demonstrates, arousal from exciting activities also can be transferred to feelings of lust and love for the partner. A similar process even seems to hold for nonhuman animals, who exhibit what has come to be known as the Coolidge effect. There is a tendency, first observed in rats but subsequently in all mammals studied, for animals initially to have repeated intercourse with an available mate. The animals will lose interest over time, but then have repeated intercourse again when introduced to new sexual partners (Beach & Jordan, 1956; Dewsbury, 1981). This phenomenon is named after former American President Calvin Coolidge. Apparently when Mrs. Coolidge was touring a farm, she was impressed with the vigorous sexual activity of a particular rooster. When she asked the attendant how often it happened and was told “Dozens of times each day,” Mrs. Coolidge suggested, “Tell that to the president when he comes by.” On hearing this, the president asked, “Same hen every time?” The reply was, “Oh, no, Mr. President, a different hen every time,” to which the president responded, “Tell that to Mrs. Coolidge.”

Now, we are by no means advocating the introduction of sexual promiscuity if a long-

Doing novel, fun, exciting things together in new places sounds like a no-

Early in relationships, couples do a lot of stimulating, fun things together. One key for couples to maintain passion over the long haul is to keep doing such activities.

[Cultura RM/JAG Images/Getty Images]

To explore the potential benefits of such self-

591

Maintaining passion and enhancing relational satisfaction takes effort, but it is effort that we can all put in if we’re motivated to do so and keep some basic ideas in mind. Approaching the relationship positively and not just seeking to keep it afloat, mutually supporting growth goals, preserving quality time alone together, and interjecting arousal and novelty are all strategies that pay off. We hope they do for those of you seeking an enriching long-

|

Long- |

|

Stay or go? The interdependence theory proposes three factors that determine commitment: satisfaction level, quality of alternatives, and investment. Decisions are also based on whether the relationship meets psychological needs. Securely attached people are more likely to leave an unsatisfying relationship. |

Daily hassles The ability to let daily hassles roll off one’s back makes for a happier relationship. Predisposed vulnerabilities and external stress make this harder to do. |

Conflict Conflict is inevitable. The partner’s ability to use voice constructively facilitates optimal compromise solutions. |

Home fires burning Maintaining a healthy relationship depends on a secure base and mutual support of growth. Emotional support also is important, as is sharing novel and enjoyable experiences together. |

|---|

CONNECT ONLINE:

Check out our videos and additional resources located at: www.macmillanhighered.com/