2.2 General Adaptations of the Cultural Animal

With an overview of evolutionary theory in place, we can ask what adaptations characterize human beings. Evolutionary psychologists tend to focus on what are known as domain-

Domain-specific adaptations

Attributes that evolved to meet a particular challenge but that are not particularly useful when dealing with other types of challenges.

In contrast, domain-

Domain-general adaptations

Attributes that are useful for dealing with various challenges across different areas of life.

Humans Are Social Beings

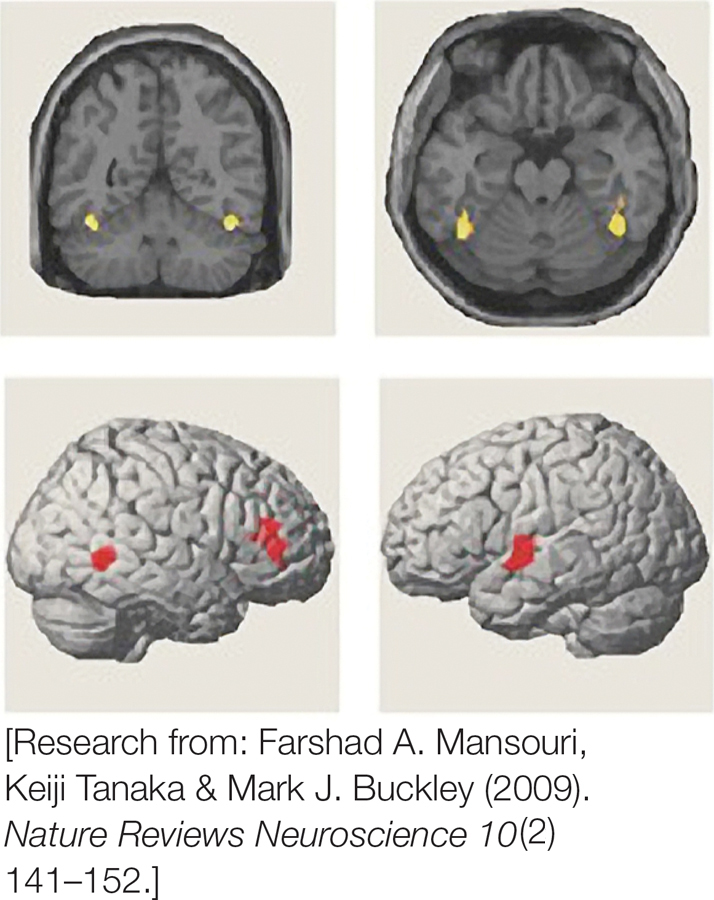

FIGURE 2.1

Fusiform Face Area

The fusiform face area allows us to recognize the faces of the people we know.

[Research from: Farshad A. Mansouri, Keiji Tanaka © Mark J. Buckley (2009). Nature Reviews Neuroscience 10(2), 141–152.]

As you’ll recall from chapter 1, the second core assumption of social psychology is that behavior depends on a socially constructed view of reality. Therefore, human sociability and social sensitivity should not be surprising. From birth on, human beings cannot survive without extensive relationships with other human beings. As infants we need caretakers to feed, protect, and comfort us; as adults virtually everyone desires and depends on friends and lovers, as well as the extended communities that help us meet our basic needs. Except for the very rare hermit, people spend their entire lives enmeshed in a complex web of connections with other human beings. In fact, most hermits are not as removed from the social world as they appear: Even Henry David Thoreau, the American writer who famously wrote of his solitary time at Walden Pond “seeking the great facts of his existence,” hung out with his friend Ralph Waldo Emerson and brought his mother his dirty laundry!

Darwin recognized that in many species, the prospects for survival and gene perpetuation are vastly improved for those who get along well with other members of their species. Because of the adaptive value of social sensitivity, the human brain has evolved several tools that help individuals react appropriately to and get along with one another. For example, there is an area in the brain called the fusiform face area, which functions specifically to recognize human faces (FIGURE 2.1) (Kanwisher et al., 1997). This ability is useful, because faces convey important information. Most obvious, each face is unique, making it possible not only to recognize individuals and recall information about them {“that’s the guy who lent me an ax”) but also to interpret what they might be thinking and feeling.

Another feature of the human brain that supports sociability is that it is very quick to pick up on the experience of being socially rejected or excluded. When rejection or exclusion occurs, it triggers a strong negative reaction in the brain. In fact, social exclusion activates an area of the brain responsible for generating feelings of physical pain (Eisenberger et al., 2003). So we generally try hard to fit in to minimize experiencing such aversive feelings.

The brain also contains an inborn readiness to categorize people in ways that increase the likelihood that social interactions will go smoothly. Both humans and other primates share a universal tendency to categorize and behave toward others along at least two distinct dimensions (Boehm, 1999; de Waal, 1996).

41

Closeness or solidarity: People quickly categorize others as friend or foe, which tells them immediately whether they can expect good things or bad things from them.

Status or hierarchy: People categorize others’ power or rank within the group so that they can determine the most appropriate way to interact with them. In both human and other primate groups, individuals respect these status hierarchies the vast majority of the time, thus averting direct confrontations and violence.

The social nature of the human animal is also reflected in a more fundamental fact of human psychology: that it is shaped by socialization. This term refers to the lifelong process of learning from others what is desirable and undesirable conduct in various specific situations. This learning occurs in our relationships with our parents, siblings, friends, teachers, and many others with whom we have significant relationships over the course of our lives.

Socialization

Learning from parents and others what is desirable and undesirable conduct in a particular culture.

The socialization process has a profound influence on people’s thought and behavior because, compared with almost all other species, humans are particularly immature when they are born. Whereas a baby turtle or spider can be zipping around the same day it is born, human infants are born in a profoundly helpless state and require years of care if they are to have any chance of survival. This extended period of immaturity and helplessness allows children to learn how to function well in the specific environment in which they develop. In so doing, our relative immaturity provides added flexibility to our species and helps to account for the incredible diversity that we see among people.

Humans Are Very Intelligent Beings

All living things are intelligent in the broad sense that they have their own ways of detecting external conditions and responding accordingly to stay alive and reproduce. In this respect, cockroaches are pretty smart—

Imagination: The Possibility of Possibilities

In the movie Casino, the human ability to imagine new possibilities enabled Sam Rothstein to envision building a series of large casinos on what was a dusty desert landscape. Although the movie may not have the facts right on Las Vegas’s history, it nicely illustrates the power of human imagination.

[© Universal/Courtesy Everett Collection]

Nevertheless, humans have the greatest intelligence in terms of their capacities for learning, symbolic thought, and imagination, and consequently, for altering their surroundings the better to meet their needs and desires. That’s why there are iguanas in Alaska and penguins in Panama. As the philosopher Søren Kierkegaard put it, by virtue of our unique form of consciousness, we humans have the “the possibility of possibilities.” (1844/1980; p. 42). Take a scene in the movie Casino (De Fina & Scorsese, 1995) in which Sam “Ace” Rothstein (played by Robert De Niro) looks out at an empty desert and says, essentially, “This is where Las Vegas will go.” No other species is capable of such audacity! Imagine a squirrel looking out on to a grassy field and saying, “This is where my acorn castle will go.”

The capacity to imagine a future unlike anything we have experienced firsthand provides the basis for a uniquely human form of control over the world in which we live. An especially important component of this capacity, making it possible to transform our wishes into reality, is the capacity to think and communicate with symbols.

Symbolic Thought and Language: The Great Liberators

What does a red light have to do with stopping, other than being a socially agreed-

42

The most important result of our symbolic thinking is that it makes language possible. Language is a tool for learning and sharing systems of symbols, which can be combined to convey a virtually infinite number of meanings. The emergence of language allowed a quantum leap in the flexibility and adaptability of the human species. It enables people to think and communicate about other people, objects, and events that are not in their current environment. Language vastly increases the sources of information that people can use to make decisions and plan action. To illustrate: Coyotes coordinate attacks on prey through the use of a variety of barks, yips and howls, but only humans can sit back and discuss their plans, recount prior military actions, and debate on nationwide call-

The Self

And then an event did occur, to Emily, of considerable importance. She suddenly realized who she was.

— Richard Hughes, A High Wind in Jamaica (1929/2010, p. 135)

Being able to think about the external world by using symbols is a powerful adaptation, but humans’ ability to think about the self by using symbols is more than just a variation on that same theme. People not only experience life but also experience the fact that they are experiencing it: I am, and I know that I am, and I know that I know that I am. Being able to represent the self symbolically as an “I” or “me” enables people to think about the meaning of their experiences. A deer confronted by a pack of wolves may experience fear, but only humans can consciously contemplate the fact that I am very afraid right now and ponder the meaning of this feeling. Only humans can feel foolish or embarrassed about their fears or even fear that they might become afraid. Only humans can fear things that don’t exist (e.g., ghosts, witchcraft) or that may or may not happen in the future, such as a relationship falling apart or a nuclear holocaust destroying the planet.

Think ABOUT

Having a self also makes it possible to evaluate one’s actions, feelings, thoughts, or overall sense of identity in light of one’s values, ambitions, and principles (“Am I the person I aim to be?”), and then to modify one’s thought and behavior to bring them in line with those standards. Can you think of a time when your actions didn’t match your sense of self? For example, you may have been aware that a sarcastic remark toward a friend conflicted with the value you place on being kind and considerate of other people’s feelings. This awareness is likely to lead you to try to adjust your behavior toward that person, or people in general, in the future.

Being able to think about the self symbolically also enables people to mentally simulate future events and to imagine various possibilities for their lives. In this way, people can delay a habitual response to a situation and consider alternative responses, to ponder the past and anticipate the future, and to ask “why?” and “what if?” questions. In a nutshell, having a concept of self that connects past, present, and future is adaptive because it vastly improves our ability to monitor and change our behavior, ultimately increasing our chances that things will go our way. Having a self gives humans freedom and flexibility in their behavior unlike that found in any other known living thing.

43

Conscious and Nonconscious Aspects of Thinking

Although humans are quite capable of being self-

Of course, the idea that human behavior is the result of nonconscious processes is not new. It is a central tenet of Freud’s psychoanalytic theory and also figured in the work of William James (1890), a prominent American psychologist whose ideas laid much of the groundwork for contemporary social psychology. James also pointed out that consciously controlled behavior can become nonconscious and automatic. An action can become habitual, such that conscious thought is no longer needed to perform it. For example, learning to play a musical instrument requires rigorous conscious attention over long hours of repetitive practice. Once musical skills have been acquired, however, playing the instrument becomes quite automatic. In fact, once these skills become habits, consciously thinking about them (for example, thinking about each finger’s placement on a flute) can interfere with smooth action (Beilock, 2011)!

The process by which a task no longer requires conscious attention is referred to as automatization. Can you see how automatization would be quite adaptive? For one thing, it allows people to get stuff done without actively thinking about the actions they are performing, freeing their minds to concentrate on other tasks. As a result of automatization, many human responses result from unconscious automatic processes, while responses to more novel, complex and challenging situations involve more conscious, controlled processes. Any given human behavior may be a result of one or the other, or a combination of both types of processes.

Automatic processes

Human thoughts or actions that occur quickly, often without the aid of conscious awareness.

Controlled processes

Human thoughts or actions that occur more slowly and deliberatively, and are motivated by some goal that is often consciously recognized.

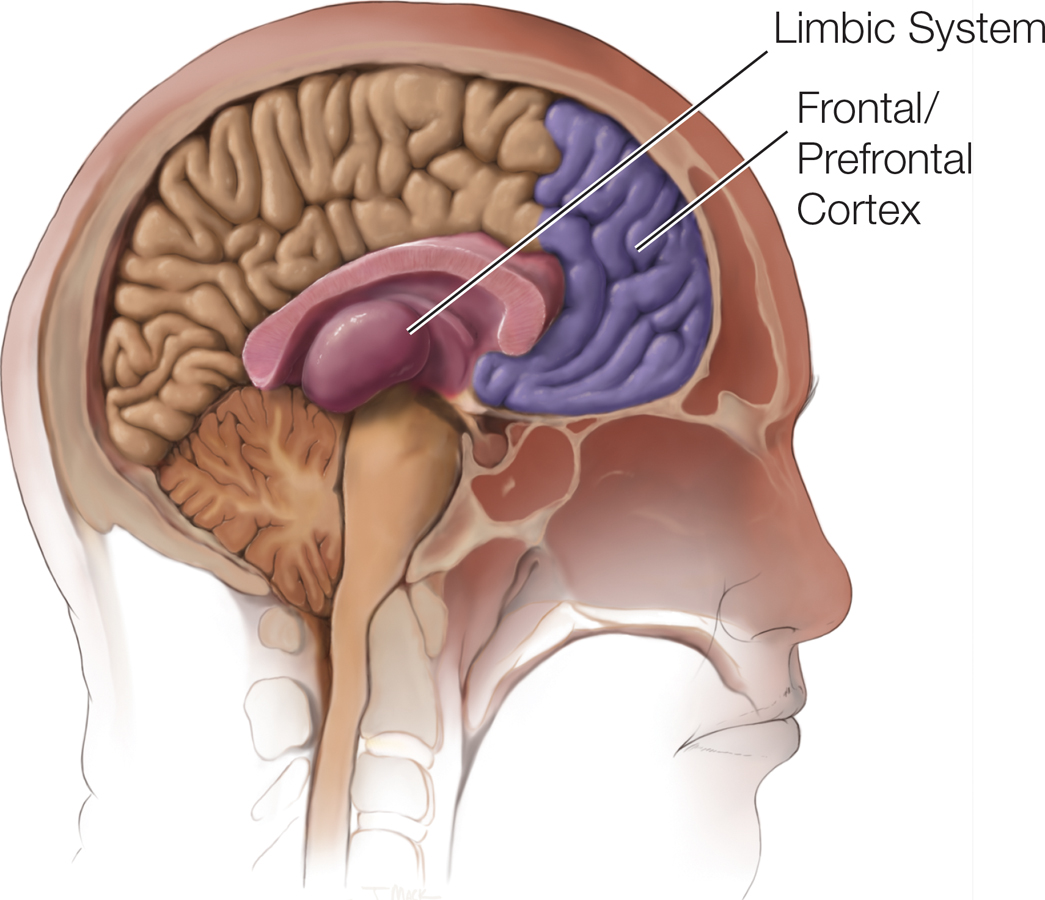

FIGURE 2.2

Limbic System and Frontal Cortex

Our experiential and rational systems take place in different regions of the brain that support different types of thought processes. Yet these systems are neurally connected and work together in producing thought and behavior.

We’ll talk more about these two processes in chapter 3; for now, we can note that humans are thought to have two mental systems that generally operate simultaneously (Epstein, 1980). One is an experiential system of thought and decision making that relies on emotions, intuitions, and images that are processed in the brain’s evolutionarily older regions, including the limbic system. Automatic processes often happen within this system (FIGURE 2.2). The other is a rational system that is logical, analytic, and primarily linguistic; this system involves greater activity from the more recently evolved frontal lobes of the cerebrum, and supports controlled processes (FIGURE 2.2). It takes over when the person has sufficient time, motivation, and cognitive resources to think carefully about her situation and herself.

People are exceptionally intelligent creatures not so much because of any single specific cognitive capacity but rather because of the whole package of verbal, nonverbal, conscious, nonconscious, experiential, and rational proclivities at their disposal. Keep in mind, too, that the mighty intellect of human beings would all be for naught without voluntary control of sensory motor systems (e.g., eye-

44

Humans Are Motivated, Goal-Striving Beings

The process of natural selection resulted in systems that energize, direct, and regulate behaviors that help people survive and prosper. In psychology, the concept of motivation refers broadly to generating and expending energy toward achieving or avoiding some outcome. Motivation can vary in strength (low to high) and in direction (toward one end state or another). Strength and direction of motivation vary from individual to individual and from situation to situation. For example, some people are motivated to lose weight, whereas others are not; among those who want to lose weight, some are highly motivated and others much less so. An upcoming high school reunion may increase a person’s motivation to lose weight much more than a pie-

Motivation

The process of generating and expending energy toward achieving or avoiding some outcome.

Needs and Goals

Humans direct their behavior toward the satisfaction of needs and goals. Needs are what is necessary for the individual to survive and prosper. Psychologists have proposed a variety of psychological needs that go beyond the minimal physical requirements for sustaining life. For example, Ed Deci and Rich Ryan’s self-

Needs

Internal states that drive action that is necessary to survive or thrive.

Goals, on the other hand, are what people strive for to meet their needs. For example, to meet your need for nutrition, you may decide to pursue the goal of getting a pizza. To meet your need for relatedness to other people, you might choose the goal of striking up a conversation with the person sitting across from you.

Goals

Cognitions that represent outcomes that we strive for in order to meet our needs and desires.

Earlier, we mentioned that human intellectual capacities operate beneath conscious awareness. The same holds for motivation: People are not always aware that their behavior is directed toward a particular goal, or what underlying need their current goals ultimately serve. Right now you are probably not consciously thinking about the goal that reading this book is serving (at least not until we just brought it up).

Hedonism: Approaching Pleasure, Avoiding Pain

Earlier, we noted that for a life-

Hedonism

The human preference for pleasure over pain.

Hedonism was adaptive in the environments in which our ancestors evolved because things that brought pleasure were generally good for our ancestors and things that brought pain were generally bad for them. Like simpler forms of life, we humans generally try to avoid what’s bad for us—

45

But this doesn’t mean that everything that appeals to people is necessarily good for them. Because hedonistic tendencies evolved over many thousands of years in environments different from those that modern humans inhabit, many things that were good for humans back then are not good for them now. Fortunately, we have the mental flexibility to step back temporarily, consider what is good and bad for us in the long run, and in this way override our evolved preferences. For example, most people innately find pleasure in sweet and fatty foods because humans’ ancient ancestors lived in harsh environments where the more calories they could get, the better. However, because of evidence that too much calorie-

The Two Fundamental Psychological Motives: Security and Growth

The concept of hedonism suggests it can be useful to think of two basic motivational orientations that guide human behavior: security (avoiding the bad) and growth (approaching the good). Neuroscience research supports the distinction between these motivational systems: Avoidance motivation involves more right-

Back in the 1930s, Otto Rank (Rank, 1932/1989; Menaker, 1982), a theorist mentored by Freud, studied how security and growth motives develop and interact over the course of the life span to influence a person’s thinking and behavior. He noted that children frequently are distressed and anxious and seek relief from these negative feelings through the nourishment, safety, and comfort provided by their parents. This means that children avoid negative emotions by establishing and sustaining a secure relationship with their loving and protective parents. This desire for security is one side of Rank’s analysis of human motivation.

The other side emerges when children are able to maintain that sense of security and as a result, begin to actively and playfully explore their surroundings in ways that expand their physical, cognitive, emotional, and interpersonal capabilities. This is the growth-

Whenever we want to understand why people behave the way they do, regardless of the specific social context, it is informative to consider the influence of these two motivational orientations. For example, people want careers that provide financial security, stability, and prestige, but at the same time are interesting and challenging. Similarly, people seek relationships with those they can trust and rely on, but whom they also find exciting and fun. We even want cars that are safe and dependable and that provide pure driving excitement!

To make sense of behavior it also helps to consider how these motivational orientations interact with each other. Rank noted that there is a complex interplay between security and growth tendencies, such that they can at times pull the person in opposite directions. In childhood, authentic desires for stimulation and new experiences often conflict with what a child’s security-

46

Rank’s analysis suggests two broad tendencies that have been highly supported by social psychological research over the last 60 years, much of which we will describe over the course of this book:

To sustain security-

However, as part of their striving for growth, people exhibit a need for uniqueness, want to express their personal views and preferences, and assert their personal freedoms when they are threatened.

The Hierarchy of Goals: From Abstract to Concrete

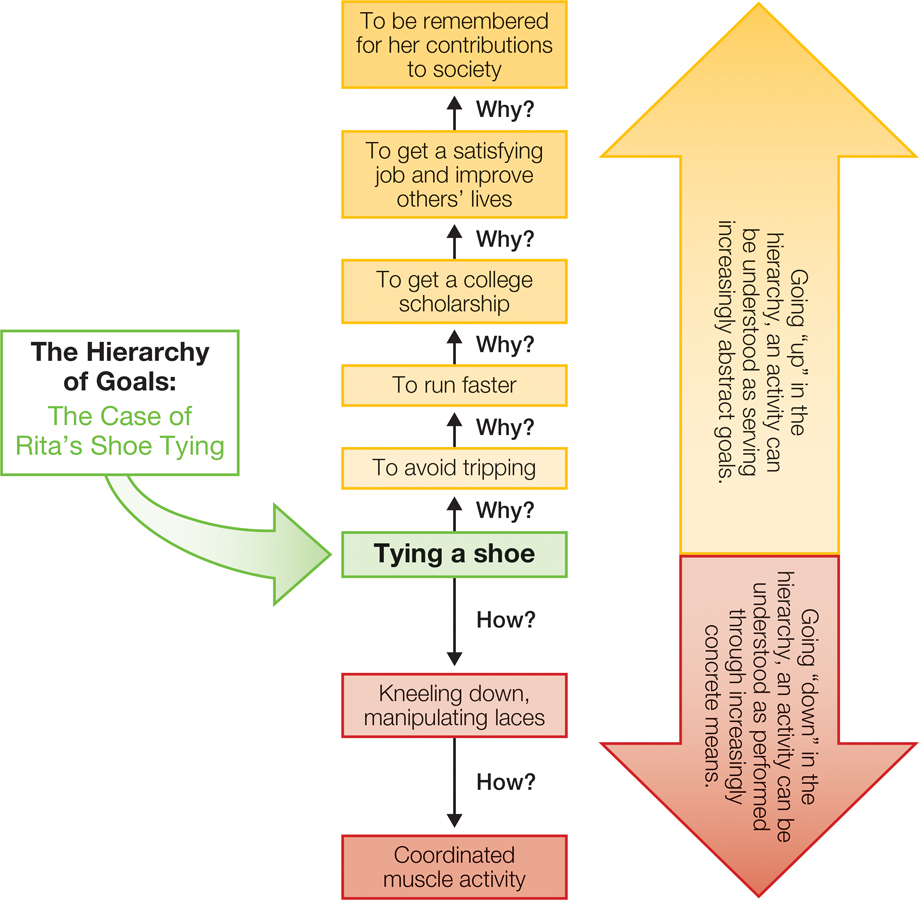

FIGURE 2.3

Rita

Goals, and the actions of which they are composed, can be represented hierarchically in terms of being more or less concrete or abstract. This figure shows how the act of tying a shoe can be connected to both coordinated muscle activity and to being remembered for societal contributions.

How do we turn our abstract goals into tangible actions? To answer these questions, we need to understand that any specific activity can be thought of as simultaneously serving many interrelated goals that can be arranged hierarchically (Carver & Scheier, 1981; Powers, 1973). This means that any goal can be understood as helping the person to achieve another, more abstract goal at a higher level in the hierarchy of standards. For example, think about a young woman who is tying her shoe; let’s call her Rita. Why is Rita doing that? Well, one obvious possibility is that she just noticed that her shoe was untied and wanted to avoid tripping on the laces. So that’s why Rita tied her shoe, and perhaps that’s all there is to it (see FIGURE 2.3).

But why is Rita concerned about tripping? Let’s suppose that Rita tied her shoe in order to run faster in a 5K race that day. She wanted to win the race to get a college scholarship in order to have better job prospects than her immigrant parents, who had to work right out of high school. And Rita wanted to attend college mainly so she could go into politics in the hope of changing the immigration laws, so people like her parents would have more productive and dignified lives. She even had hopes of becoming the first female president and winning a Nobel Peace Prize for her efforts to improve the lives of others and ultimately be remembered for hundreds or, better yet, thousands of years. So that’s why Rita tied her shoe: to win the race to go to college on an athletic scholarship to avoid working at Wal-

Hierarchy of goals

The idea that goals are organized hierarchically from very abstract goals to very concrete goals, with the latter serving the former.

47

If low-

In addition, Robin Vallacher and Dan Wegner’s (1987) action identification theory suggests that the challenges people face in the moment also affect how they are likely to describe their actions. For example, you may describe your goal at this moment as getting your social psych reading assignment done, rather than describing it more concretely as moving your eyes across the page or more abstractly as progressing toward a professional career. But when action bogs down because of challenges, people often shift to lower levels of action description. For example, if Rita fumbles with getting her shoe tied, her action identification shifts to lower levels so that she can make the appropriate adjustments to her shoe-

Humans Are Very Emotional Beings

A key component of the motivational system is emotion. Darwin (1872) asserted that emotions signal important changes in bodily states and environmental circumstances. Consequently, both the experience and anticipation of emotions play a critical role in motivating behavior; they both energize and direct the actions that people pursue.

Positive emotions reinforce one’s own successful actions and the actions of others that benefit the self. Positive emotions (such as happiness) and the expectation of them also provide motivation and energy directed toward improving one’s efforts to learn, achieve, help others, and grow (Fredrickson, 2001). Negative emotions (such as fear) and the expectation of them motivate a person to avoid actions and others that could be harmful. In addition, perceiving that the self has fallen short of an important goal or standard generates negative emotion, spurring the individual to engage in actions to alleviate that negative emotion. In these basic ways, emotions serve the important function of motivating action by kicking the person into gear when something needs to be done to reach his or her goals and, ultimately, satisfy physical and psychological needs.

The internal experience of emotion is accompanied by external displays. These expressions arise automatically and help to prepare the body to act appropriately. For example, scrunching the nose and mouth in disgust limits air intake, which can be important if dangerous airborne germs are afloat (Chapman et al., 2009). But in humans these displays take on the added function of communicating our feelings to others (Shariff & Tracy, 2011). In humans, emotional displays are most prominently communicated by facial expressions, but posture, vocalizations, and other cues also convey our feelings.

48

How do we know that these nonverbal displays of emotion are partly meant to communicate feelings to others? One piece of evidence is that they are typically more prominent when they can be witnessed by others than when they cannot. Consider adults at a bowling alley. Research shows that when they get a strike, they rarely smile while they face down the alley at the pins, but they smile frequently when they turn around to face their friends sitting behind them (Kraut & Johnston, 1979). This finding suggests that emotions are not merely private matters; rather, they help others understand a person’s current mental state and plan an appropriate response. In this way, emotions support the social nature of humans, which we discussed earlier.

The Wide-Ranging Palette of Emotions

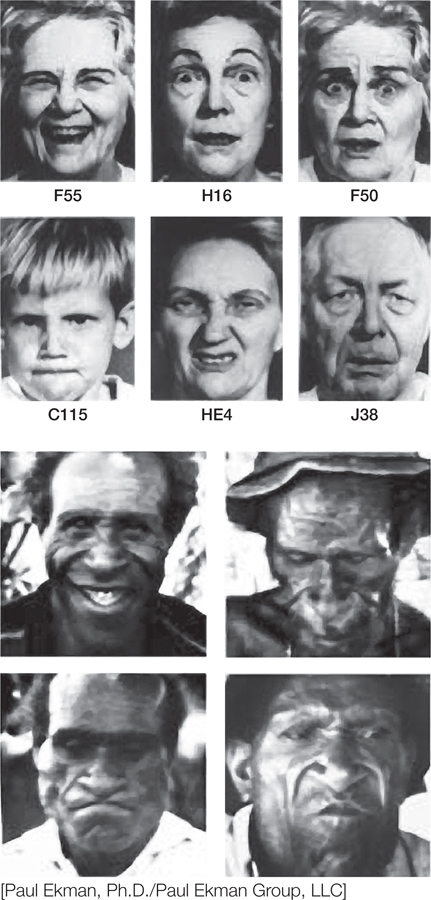

FIGURE 2.4

Cultural Similarities in Emotional Expression

Evidence that people across diverse cultures recognize the same emotional expressions suggests that at least some emotions are universally experienced.

What emotions do humans experience? What triggers these emotions? Contemporary emotion researchers generally distinguish several categories of emotions. For example, the neurologist Antonio Damasio (1999) proposed a three-

Background Emotions: Background emotions make up an individual’s general affective tone at a given moment. As the term implies, these emotions are in the psychological background and provide what some German writers call Lebensgefühl, or “sense of life” (Langer, 1982). Another way to think about background emotions is that, for an emotionally unimpaired person, there’s never a waking moment in which he or she has no feelings or emotions. People always feel something, even if only vaguely, making it fairly likely that they’ll experience other, more specific emotions. These background feelings are what we typically refer to when we say we are in a good or bad mood.

Primary Emotions: Whereas mood tends to be a diffuse general feeling that is often not the focus of our attention, at other times we are acutely aware of feeling a specific emotion. Research suggests that there are six primary emotions: happiness, sadness, fear, anger, surprise, and disgust. All humans seem to be born with the capacity to experience these basic emotions. Three sets of findings support this conclusion. First, for people around the world, these emotions tend to be triggered by the same types of stimuli in the physical and social environments (Lazarus, 1991; Mesquita & Frijda, 1992; Rozin & Fallon, 1987). For example, humans typically experience sadness when a loved one dies and disgust when confronted with a rotting animal carcass.

Second, the experience of these emotions involves brain structures, such as the amygdala and the anterior cingulate cortex, that developed very early in human evolution (Ekman & Cordaro, 2011; Lindquist et al., 2012). Third, these emotions are associated with distinctive facial expressions that are recognized easily by people the world over (Ekman, 1980; Izard, 1977). For example, members of geographically isolated tribes in New Guinea, who have never before encountered Americans, can accurately recognize primary emotions conveyed by the facial expressions of an American; and Americans with no experience with New Guineans are equally adept at interpreting the facial expressions of members of these isolated tribes (FIGURE 2.4 shows the pictures of emotional expressions used in this research). The clearest interpretation of these findings is that these emotions are innate, at least to a large degree.

Secondary Emotions: We often experience secondary emotions that are variations on the six primary emotions. For example, joy, ecstasy, and delight are variations of happiness; gloom, misery, and wistfulness are variations of sadness; panic, anxiety, and terror are variations of fear. Another group of secondary emotions includes the social emotions, which depend on even more recent brain structures, specifically the frontal lobes (see FIGURE 2.2). These include sympathy, embarrassment, shame, guilt, pride, jealousy, envy, gratitude, admiration, indignation, and contempt. These emotions also appear similarly across diverse cultures.

49

Social emotions regulate social behavior by: (1) drawing the person’s attention to socially inappropriate behavior; (2) reinforcing appropriate social behavior; and (3) helping to repair disrupted social relationships. So we feel proud of the good things we do and guilty about the bad things. Those feelings of guilt provoke attempts to apologize to people we have hurt (Tracy & Robins, 2004).

How Cognitions Influence Emotions

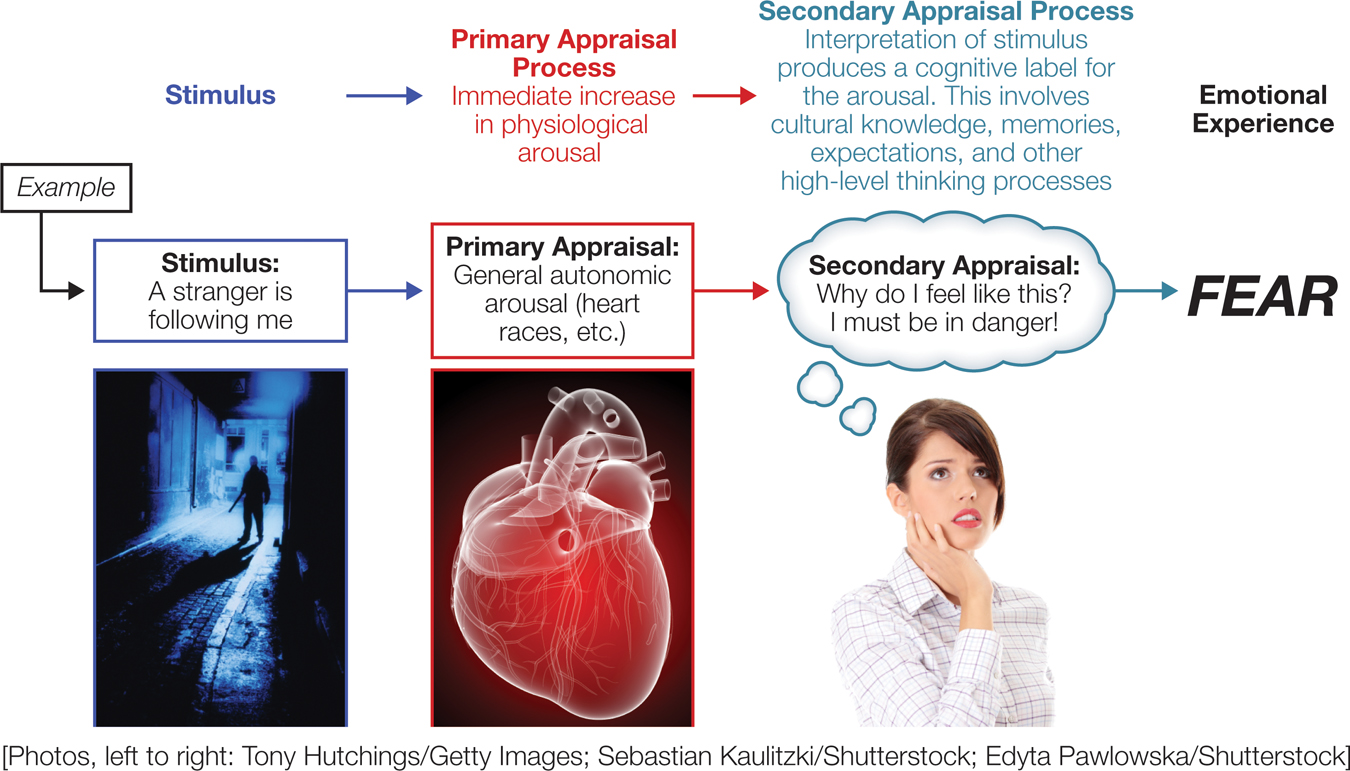

Primary emotions involve rather general and diffuse activation of specific bodily systems, including specific brain regions, the autonomic nervous system, and facial muscles (Lazarus 1991; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984; Mandler, 1984; Schachter & Singer, 1962). However, the various subtle shades of emotional experience depend on higher-

Cognitive appraisal theory

The idea that our subjective experience of emotions is determined by a two-

FIGURE 2.5

Lazarus’s Cognitive Appraisal Theory of Emotions

Lazarus’s theory of emotions explains how our appraisals of a stimulus help to determine the specific emotion that we feel. How would the woman’s emotion change if the secondary appraisal revealed that it was her best friend following her?

Discovering that someone is in your apartment will elicit an immediate jolt of arousal, but the realization that it’s a surprise party for your birthday will engage a secondary and more positive emotional response.

Once we experience arousal and an initial emotional response, we are likely to engage in a secondary appraisal process to assess the environment further. This secondary appraisal often leads to a refinement, a modification, or even a change in the nature of the emotion people experience. At this point, the rational processing system (Epstein, 1980, 2013) gets involved as we consider memories, cultural influences, and thoughts of future ramifications. This can lead to a very different emotional response than we experienced from the primary appraisal process. This secondary appraisal involves activity in the prefrontal lobes, a part of the brain associated with consciousness and high-

50

One of our colleagues recently experienced this two-

How Emotions Affect Cognition

Just as cognition influences emotions, emotions also affect cognitions. In examining this influence, researchers have focused primarily on the impact of background emotion—

A variety of experimental procedures have been developed to put people in temporary good or bad moods, such as showing people funny or sad videos. When positive moods are triggered, people make more positive judgments about themselves, other people, and events; they make more optimistic predictions about the future; and they find it easier to recall positive memories. In contrast, bad moods lead people to view most things more negatively, to recall more negative memories, and to have more negative expectancies (Bower & Forgas, 2000; Isen, 1987). In addition, people in a good mood don’t analyze things too much but rely instead on their preexisting knowledge in making judgments. In contrast, people in negative moods think more intensely about themselves and their environment in an attempt to understand what they are experiencing. Presumably, this occurs because whereas a positive mood signals that everything is fine, a bad mood signals that something is not right and needs to be rectified.

Specific primary and secondary emotions can also influence cognition by directing attention, memory, and interpretation in particular ways—

Emotions also influence cognitions in a less obvious manner. Emotions are typically viewed as impediments to rational thought. How many times have all of us been told to stop being so emotional and be “reasonable”? Indeed, strong emotions can at times makes it impossible to think logically. Nevertheless, emotions are utterly necessary for rationality and good decision making, especially in matters pertaining to complex social judgments. Recall that the frontal lobes are important for the social emotions described previously (see FIGURE 2.2). In Descartes’ Error, Antonio Damasio (1994) describes studies of people with frontal-

51

|

General Adaptations of the Cultural Animal |

|

Over the course of evolution, human beings inherited four domain- |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Humans are: |

|||

|

Social Beings People seek connection and avoid exclusion. People quickly decide whether and how to interact with others. People are profoundly shaped by socialization throughout their lives. |

Very Intelligent Beings People have an unprecedented capacity to: imagine things that do not exist; think about the world using symbols and language; contemplate why things happen; and conceive of themselves and their experiences across time. People think using two systems: an experiential system (intuitive, nonconscious, automatic) and a controlled system (rational, conscious, effortful). |

Motivated, Goal- Needs are necessary for survival; striving for goals is how people meet their needs. Both can influence behavior without awareness. Hedonism is the motivation to approach pleasure and avoid pain. It is reflected in two fundamental human motivations: growth and security. Humans can arrange goals hierarchically, allowing flexibility in self- |

Very Emotional Beings Emotions help people self- Humans have background, primary, and secondary emotions. The experience of emotions is influenced by an initial rapid physiological response, followed by a secondary appraisal of the situation. Emotions and cognitions affect each other. |