4.2 Inferring Cause and Effect in the Social World

Now that we have a sense of the role of memory in how we understand people and events, we can move on to a second core process we use to gain understanding. This is the process by which we look for relationships of cause and effect. In our fender-

Common Sense Psychology

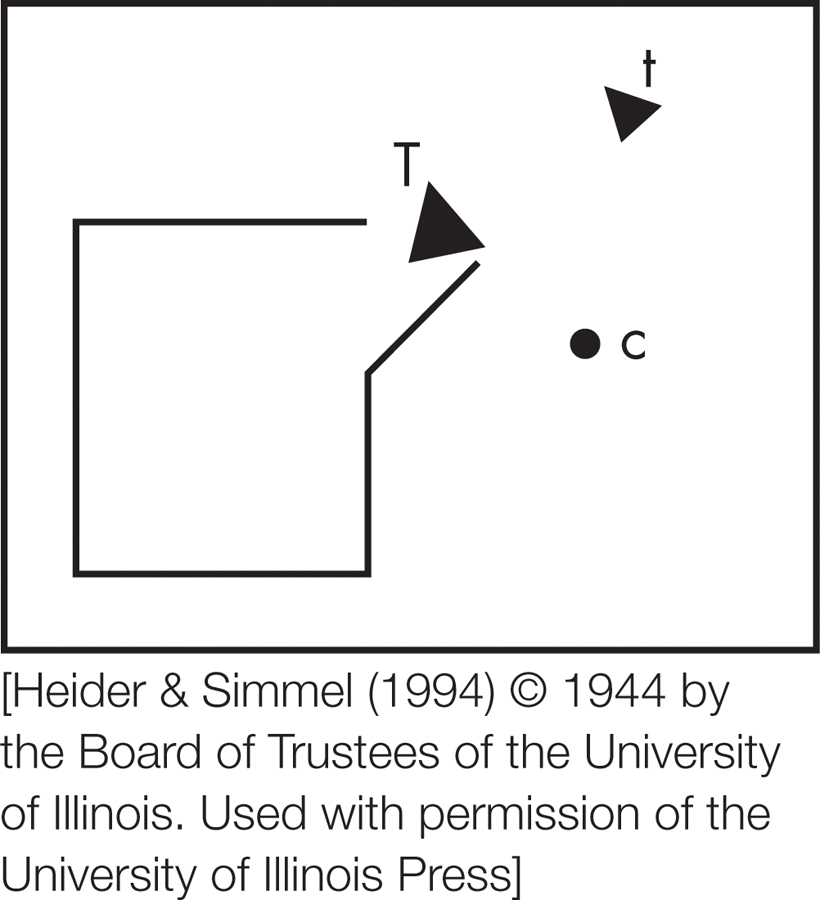

FIGURE 4.3

Seeing Intention

People tend to perceive actions in the world in terms of cause and effect. In viewing these shapes, subjects perceived the scene as one triangle pushing the other out of the room.

[Heider & Simmel (1994) © 1944 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois. Used with permission of the University of Illinois Press]

Working from a Gestalt perspective, Heider assumed that the same kinds of rules that influence the organization of visual sensations also guide most people’s impressions of other people and social situations. In one early study (Heider & Simmel, 1944), people watched a rather primitive animated film in which a disk, a small triangle, and a larger triangle moved in and out of a larger square with an opening. The participants were then asked to describe what they saw (FIGURE 4.3). People tended to depict the actions of the geometric objects in terms of causes, effects, and intentions, for example, “The larger triangle chased the smaller triangle out of the room [the larger square].”

This tendency led Heider to propose that people organize their perceptions of action in the social world in terms of causes and effects. He subsequently listened to how people talked about their social lives in ordinary conversation and obtained further support for this proposition. Specifically, people tend to explain events in terms of particular causes. Heider referred to such explanations as causal attributions.

Causal attribution

The explanation that people use for what caused a particular event or behavior.

126

Because causal attributions help people make sense of, and find meaning in, their social worlds, they are of great importance. When someone is bumped into in a bar, whether he attributes the bumping to malicious intent or mere clumsiness can be a matter of life or death. When an employee is late, whether the employer attributes that behavior to the person’s laziness or to her tough circumstances can determine whether she is fired or not. After a car accident, determining who was responsible can have profound financial consequences for the parties involved. If a woman shoots her abusive husband, a jury may have to decide if she did it because she feared for her life or because she wanted to collect on his life insurance. Whenever the economy is shaky, considerable debate arises over which political party’s policies are most responsible for the current economic gloom. In pretty much every domain of life, from bar jostling to jurors’ decision making to whom one votes for on election day, causal attributions play a significant role.

Basic Dimensions of Causal Attribution

Heider (1958) observed that causal attributions vary on two basic dimensions. The first dimension is locus of causality, which can be either internal to some aspect of the person engaging in the action (known as the actor), or external to some factor in the person’s environment (the situation). For example, if Justin failed his physics exam, you could attribute his poor performance to a lack of intelligence or effort, factors internal to Justin. Or you could attribute Justin’s failure to external factors, such as a lousy physics professor or an unfair exam.

Locus of causality

Attribution of behavior to either an aspect of the actor (internal) or to some aspect of the situation (external).

The second basic dimension is stability: attributing behavior to either stable or unstable factors. If you attribute Justin’s failure to a lack of intelligence, that’s a stable internal attribution, because people generally view intelligence as relatively immutable. On the other hand, if you attribute Justin’s failure to a lack of effort, that is an unstable internal attribution. You would still perceive Justin as responsible for the failure, but you would recognize that his exertion of effort can vary from situation to situation. Stable attributions suggest that future outcomes in similar situations, such as the next physics test, are likely to be similar. In contrast, unstable attributions suggest that future outcomes could be quite different; if Justin failed because of a lack of effort, he might do a lot better on the next test if he exerted himself a bit more.

External attributions can also be stable or unstable. If you attribute Justin’s failure to a professor who always gives brutal tests or who is an incompetent teacher, you are likely to think that Justin will not do much better on the next test. But if you attribute Justin’s failure to external unstable factors such as bad luck or his girlfriend’s having broken up with him right before the test, then you’re more likely to think Justin may improve on the next exam.

Getting children, including girls, to attribute math performance to effort rather than natural ability can improve math performance.

[Blend Images/Ariel Skelley/Getty Images]

As poor Justin’s example suggests, how we attribute a behavior—

APPLICATION: School Performance and Causal Attribution

|

APPLICATION: |

| School Performance and Causal Attribution |

These attributional processes don’t just affect how we perceive others. They can also influence how we perceive ourselves. The psychologist Carol Dweck (1975) investigated the causal attributions that elementary-

127

Entity and Incremental Theorists

Inspired by her early work on achievement, Dweck and colleagues (Dweck, 2012; Hong et al., 1995) proposed that intelligence and other attributes need not be viewed as stable entities. Rather, they could be viewed as attributes that change incrementally over time. Dweck says that when we take the perspective of an entity theorist, we view an attribute as a fixed trait that a person can’t control or change. For example, we may see an attribute such as intelligence as a stable and enduring quality. But when we take the perspective of an incremental theorist, we believe an attribute is a malleable ability that can increase or decrease. For example, we may see an attribute such as shyness as a quality that, with the right motivation and effort, people can change (Beer, 2002). Take a moment to think about which attributes you think are fixed entities and beyond your control, and which attributes you think are changeable.

These theories have implications for how an individual interacts with, and responds to, the social world. Dweck and colleagues find that entity theorists, both children and adults, make more negative stable attributions about themselves in response to challenging tasks, and then tend to perform worse and experience more negative affect in response to such tasks. Moreover, they tend to eschew opportunities to change that ability even when the ability is crucial to their success. For instance, one study measured peoples’ theories about achievement and intelligence. Exchange students who had stronger entity theories expressed less interest in remedial English courses when their English was poor and improving would facilitate their academic goals (Hong et al., 1999). In contrast, incremental theorists view situations that implicate that ability more as opportunities to improve, to develop their skills and knowledge. This affects not just what we do for ourselves, but also how we treat others. When business managers had stronger incremental theories, they were more willing to provide mentorship to their employees and thus help their employees to improve (Heslin & Vanderwalle, 2008).

Although people generally have dispositional tendencies to hold either entity or incremental theories about human attributes, these views can be changed (Dweck, 2012; Heslin & Vanderwalle, 2008; Kray & Haselhuhn, 2007). For example, research has shown that convincing students that intelligence is an incremental attribute rather than a stable entity encourages them to be more persistent in response to failure, adopt more learning-

128

Automatic Processes in Causal Attribution

How do people arrive at a particular attribution for a behavior they observe? Like most products of human cognition, casual attributions sometimes result from quick, intuitive, automatic processes, and sometimes from more rational, elaborate, thoughtful processes.

Whenever you ask people why some social event occurred, they can usually give an opinion. However, research has shown that people often don’t put much effort into thinking about causal attributions. People make a concentrated effort primarily when they encounter an event that is unexpected or important to them (Jaynes, 1976; Pyszczynski & Greenberg, 1981; Wong & Weiner, 1981). Such events are more likely to require some action on our part and are more likely to have a significant impact on our own lives, so it is more important to arrive at an accurate causal attribution.

Let’s imagine that when you were a kid, your mom always had coffee in the morning, and you came into the kitchen one morning and saw your mom put on a pot of coffee. If a friend dropped by and asked you why your mom was doing that, you would readily respond, “She always does that” or “She loves coffee in the morning”—the same knowledge that led you to expect her to do exactly what she did. However, if one morning she was brewing a pot of herbal tea, this would be unexpected, and you’d likely wonder why she was doing that instead of brewing her usual coffee. You would be even more likely to think hard about a causal attribution for her behavior if one morning she was making herself a martini.

129

Most events in our daily lives are expected; consequently, we don’t engage in an elaborate process to determine a causal attribution. According to Harold Kelley (1973), when events readily fit existing causal schemas, we rely on them rather than engage in much thought about why the events occurred. These causal schemas come from two primary sources. Some are based on our own personal experience, as in the mom-

The Fundamental Attribution Error

When an event we observe isn’t particularly unexpected or important to us but doesn’t readily fit an obvious causal schema, we are likely to base our causal attribution on whatever plausible factor is either highly visually salient or highly accessible from memory. This “top of the head phenomenon” was illustrated in a set of studies by Shelley Taylor and Susan Fiske (Taylor & Fiske, 1975; Fiske & Taylor, 1991) in which participants heard a group discussion at a table. One particular member of each group was made visually salient. One way they accomplished this was by having only one member of the group be of a particular race or gender. Participants were asked how much each individual was responsible for the direction of the discussion. For instance, when the group included only one woman, she was viewed as most causally responsible for the discussion. Similar effects have been found if salience is achieved by having the person sitting at the apparent head of a table or if lighting is specifically focused on the person (McArthur & Post, 1977).

This reliance on visual salience was anticipated by Heider, who proposed that people are likely to attribute behavior to internal qualities of the person, because when a person engages in an action, that actor tends to be the observer’s salient focus of attention. Edward Jones and Keith Davis (1965) carried this notion further by proposing that when people observe an action, they have a strong tendency to make a correspondent inference, meaning that they attribute an attitude, desire, or trait that corresponds to the action to the person. For example, if you watch Ciara pick up books dropped by a fellow student leaving the library, you will automatically think of Ciara as helpful. These correspondent inferences are generally useful because they give us quick information about the person we are observing.

Correspondent inference

The tendency to attribute to the actor an attitude, desire, or trait that corresponds to the action.

Correspondent inferences are most likely under three conditions (e.g., Jones, 1990). First, the individual seems to have a choice in taking an action. Second, a person has a choice between two courses of action and there is only one difference between one choice and the other. For example, if Sarah must choose between two colleges that are very similar except one is known to be more of a party school, and she chooses the party school, you may conclude Sarah is into partying. But you would be less likely to do so if the school she chose was more of a party school, but was also closer to her home, in a warmer climate, was known to be better in science, and was less expensive. Third, a correspondent inference is more likely when someone has a particular social role and acts inconsistent with that role. If a contestant in a game show such as The Price is Right wins a car but barely cracks a smile and simply says “Thank you,” you would be likely to infer she is not an emotionally expressive person. But if she jumps up and down excitedly after she wins the new car, you would not be as certain what she is like, because most people in that role would be similarly exuberant.

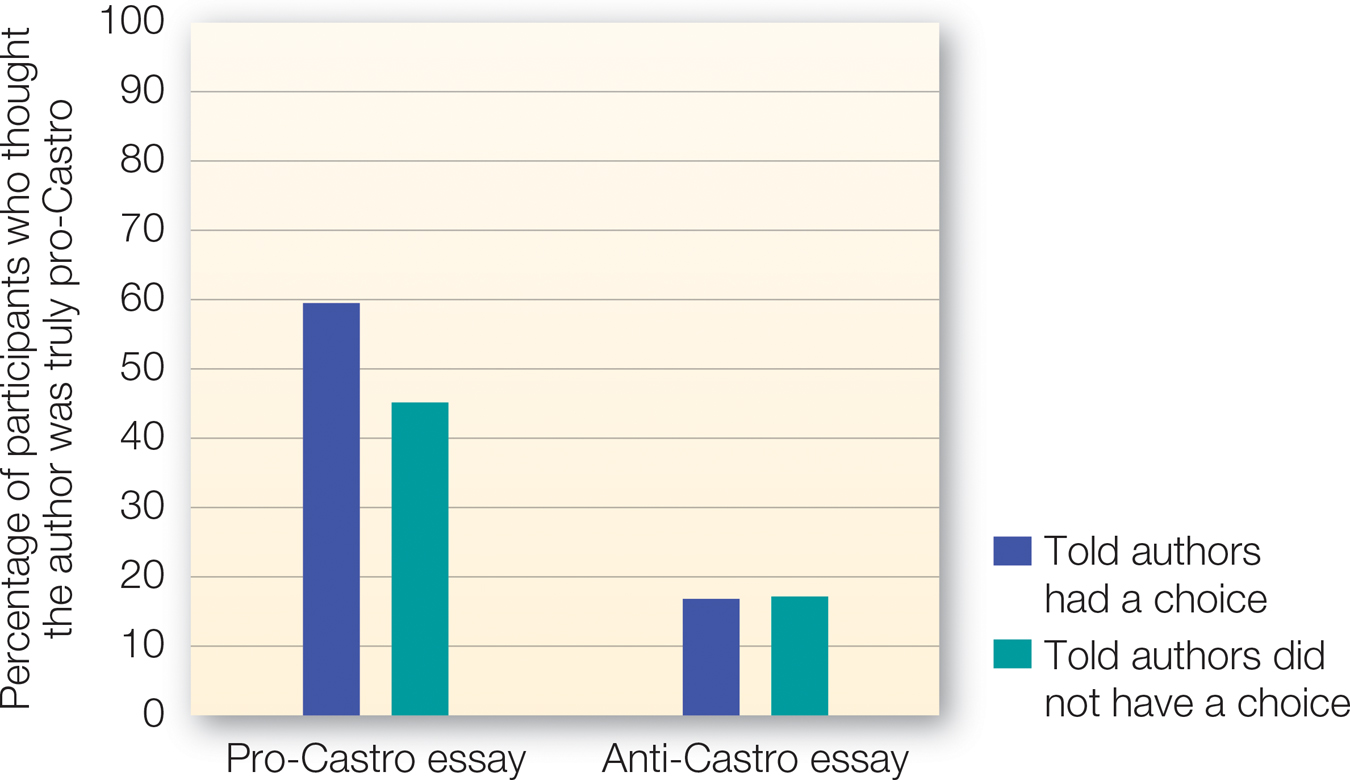

Although all three of these factors increase the likelihood of a correspondent inference, this tendency is so strong that we often jump to these correspondent inferences without sufficiently considering external, situational factors that may also have contributed to the behavior witnessed (e.g., Jones & Harris, 1967). Research has found that people’s tendency to attribute behavior to internal or dispositional qualities of the actor, and consequently underestimate the causal role of situational factors, is so pervasive that it is known as the fundamental attribution error, or FAE for short. The initial demonstration of the FAE was provided by Ned Jones and Victor Harris (1967) (FIGURE 4.4). Participants read an essay that was either strongly in favor of Fidel Castro (the longtime dictator of Cuba) or strongly against Castro. Half the participants were told that the essay writer chose his position on the essay. When asked what they thought the essay writer’s true attitude toward Castro was, participants, not surprisingly, judged the true attitude as pro-

Fundamental attribution error (FAE)

The tendency to attribute behavior to internal or dispositional qualities of the actor and consequently underestimate the causal role of situational factors.

FIGURE 4.4

The Fundamental Attribution Error

Participants inferred that the author’s true attitude matched the position advocated in the essay, even when told the author had no choice in what position he took for the essay.

[Data source: Jones & Harris (1967)]

130

Many experiments have since similarly shown that despite reasons for attributing behavior largely, if not entirely, to situational factors, people tend to make dispositional attributions instead. One of the most compelling demonstrations was a study by Lee Ross and colleagues (1977), inspired by early precursors, which date back to the 1950s, to the present plethora of reality TV shows: quiz shows. Participants were randomly assigned the role of questioner, contestant, or observer, which ensured that the groups of students assigned to each role were equally knowledgeable. The questioners were asked to generate difficult questions that the contestants then had to answer. It is pretty obvious that coming up with tough questions from your own store of knowledge is a lot easier than answering difficult questions made up by someone else. Yet, both the observers and the contestants themselves concluded that the questioners were more knowledgeable than the contestants. Clearly these participants did not take sufficiently into account the influence of the situation—

A compelling example of the FAE from everyday life is the tendency to think that actors are like their characters. Actors who play evil characters on soap operas have even been verbally abused in public! Leonard Nimoy, who played Mr. Spock in the original Star Trek television show and in subsequent movies, got so tired of being viewed as Spock when the series was at the height of its popularity that he wrote a book called I Am Not Spock. Similarly, slapstick comics such as Will Far

The FAE has implications for how people judge others—

How Fundamental Is the FAE?

Although the FAE is common when people make attributions for the behavior of others, this is not the case when making attributions for oneself. And if you think about visual salience, you should be able to (literally) see why. When we are observers, the other person is a salient part of our visual field, but when we ourselves are acting in the world, we are usually focused on our surroundings rather than on ourselves. This leads to what has been labeled the actor-

Actor-observer effect

The tendency to make internal attributions for the behavior of others and external attributions for our own behavior.

Nisbett and colleagues (1973) asked people either why their roommates had chosen their majors or why they had chosen their own. Participants made internal attributions for the roommate’s choice: “Chris chose psychology because she loves analyzing people.” But when explaining their own choice, they emphasized attributes of the major: “Criminal justice is a fascinating field, and it allows me to consider a wide range of fields: police work, the FBI, law school, or teaching.” It is interesting that the actor-

The actor-

[Monkey Business Images/Shutterstock]

131

The actor-

There are, however, important qualifications to the actor-

Does the FAE Occur Across Cultures?

Some social psychologists have proposed that the FAE is a product of individualistic cultural worldviews, which emphasize personality traits and view individuals as fully responsible for their own actions (Watson, 1982; Weary et al., 1980). In fact, the original evidence of the FAE was gathered in the United States and other relatively individualistic cultures. And it does seem clear, as we noted in chapter 2, that people in more collectivistic cultures are more attentive to the situational context in which behavior occurs. They also are more likely to view people as more influenced by, and indeed part of, the larger groups to which they belong. In fact, when directed to explain behavior, rather than focusing on an individual, people from more collectivistic cultures (e.g., China) generally give more relative weight to external, situational factors than do people from more individualistic cultures (Choi & Nisbett, 1998; Miller, 1984; Morris & Peng, 1994). Such research suggests that socialization in a collectivist culture might sensitize people to contextual explanations of behavior. More recent research also has suggested a weaker tendency to commit the fundamental attribution error among those of lower socioeconomic status (Varnum et al., 2011) and among Catholics compared with Protestants (Li et al., 2012).

Evidence of cross-

132

Dispositional Attribution: A Three-Stage Model

Although the FAE is very common and sometimes automatic, even people from individualistic cultures often take situational factors into account when explaining behavior. In the original Jones and Harris (1967) study, for example, participants who knew that the essay writer had no choice were less confident that the essay represented the writer’s true opinions. When might people consider these situational factors before jumping to an internal attribution?

To answer this question, Dan Gilbert and colleagues (1988) proposed a model in which the attribution process occurs in a temporal sequence of three stages.

A behavior is observed and labeled: “That was a pro-

Castro statement,” or “That was helpful behavior.” Observers automatically make a correspondent dispositional inference.

If observers have sufficient accuracy motivation and cognitive resources available, they modify their attributions to take salient situational factors into account.

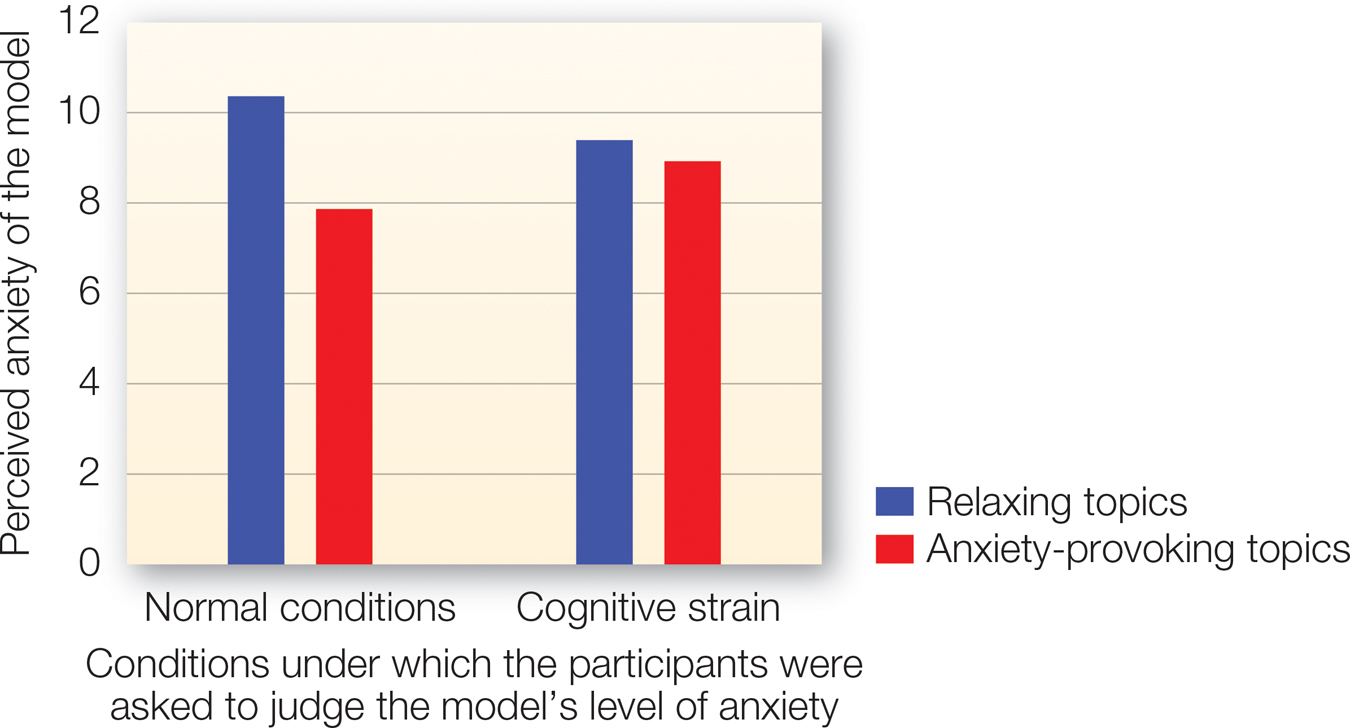

FIGURE 4.5

On Second Thought

People who are cognitively strained are less likely to correct their dispositional judgments of others. In this study, participants under normal conditions did not perceive an anxious-

[Data source: Gilbert et al. (1988)]

This model predicts that people will be especially likely to ignore situational factors and to make the FAE when they are cognitively challenged and thus have limited attention and energy to devote to attributional processing.

Putting this model to the test, Gilbert and colleagues (1988) had participants watch a videotape of a very fidgety woman discussing various topics. The participants were asked to rate how anxious a person she generally was. The videotape was silent, ostensibly to protect the woman’s privacy, but participants were shown one-

If observers have sufficient resources, they should initially jump to an internal attribution for the fidgety behavior and view the woman as anxious, but in the condition in which the topics are anxiety provoking, they should make a correction and view the woman as less anxious. Indeed, as FIGURE 4.5 shows, this is what happened under normal conditions. But half the observers were given a second, cognitively taxing task to do while viewing the videotape. Specifically, they were asked to memorize the words in the subtitles displayed at the bottom of the screen. Under such a high cognitive load, these participants lacked the resources to correct for the situational factor (the embarrassing topics) and therefore judged the anxious-

133

This three-

Elaborate Attributional Processes

So far, we have discussed primarily the relatively quick, automatic ways people arrive at causal attributions: relying on salience, jumping to a correspondent inference, and then perhaps making a correction. But what happens when we encounter very unexpected or important events? As we noted earlier, when people are sufficiently surprised or care enough, they put effort into gathering information and thinking carefully before making a causal attribution. Imagine a young woman eager about a first date with a young man she met in class and really liked; they were going to meet at a restaurant at 7:00 p.m. But he’s not there at 7:00, or 7:05, or 7:15. She would undoubtedly begin considering casual explanations for this unexpected, unwelcome event: Did he change his mind? Was he in a car accident? Is he always late?

Causal Hypothesis Testing

Putting conscious effort into making an attribution is like testing a hypothesis (Kruglanski, 1980; Pyszczynski & Greenberg, 1987; Trope & Liberman, 1996). First, we generate a possible causal hypothesis (a possible explanation for the cause of the event). This could be the interpretation we’d prefer to make, the one we fear the most, or one based on a causal schema (a theory we hold about the likely cause of that specific kind of event). A large paw print seems more likely caused by a bear than by a rabbit (Duncker, 1945). The causal hypothesis could also be based on a salient aspect of the event or a factor that is easily accessible from memory. Finally, causal accounts can also be based on close temporal and spatial proximity of a factor to the event, particularly if that co-

Covariation principle

The tendency to see a causal relationship between an event and an outcome when they happen at the same time.

Once we have an initial causal hypothesis, we gather information to assess its plausibility. How much effort we give to assessing the validity of that information depends on our need for closure versus our need for accuracy. If the need for closure is high and the need for accuracy is low, and if the initial information seems sound and fits the hypothesis, we may discount other possibilities. But if the need for accuracy is higher than the need for closure, we may carefully consider competing causal attributions, and then decide on the one that seems to best fit the information at our disposal. What kinds of information would we be most likely to use to inform our causal attributions?

134

Three Kinds of Information: Consistency, Distinctiveness, and Consensus

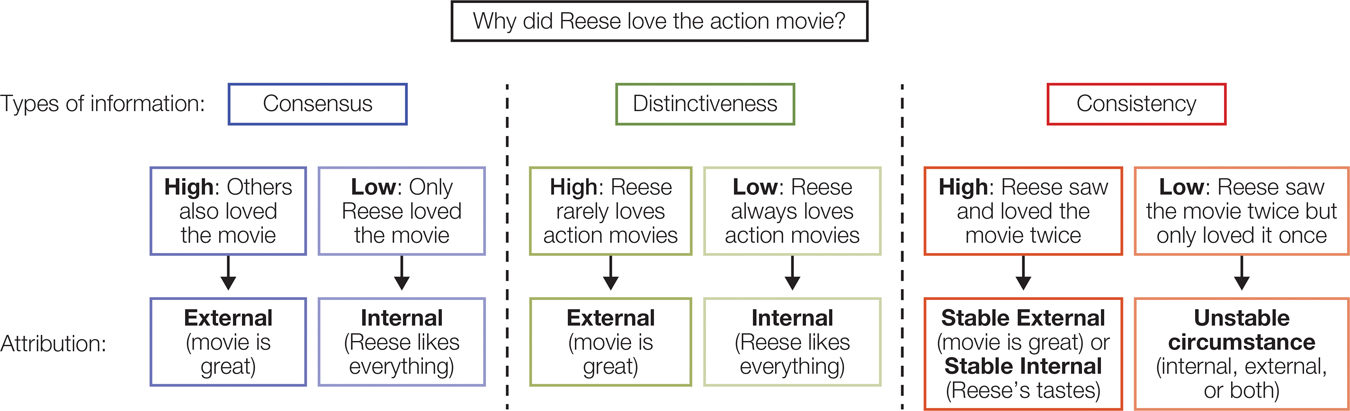

FIGURE 4.6

The Covariation Model

When an attribution is high in consistency, consensus, and distinctiveness, we attribute the behavior (Reese’s love of the movie) to an external cause. (The movie must be great!)

Harold Kelley (1967) described three sources of information for arriving at a causal attribution when accuracy is important: consistency (across time), distinctiveness (across situations), and consensus (across people) (FIGURE 4.6).

Imagine that a few years from now, Reese, an acquaintance of yours, goes to see Sylvester Stallone’s anxiously anticipated new film Rocky 9. (New regulations in boxing have made it legal to bring a walker into the ring.) Reese tells you, “You have to see this flick; it’s an unprecedented cinematic achievement.” By this time, it costs $30.00 to see a film, so you want to think hard before shelling out that kind of cash. Ultimately, you want to know if Rocky 9 is indeed a must-

SOCIAL PSYCH at the MOVIES

Casablanca

Casablanca

The 1942 Hollywood classic Casablanca, directed by Michael Curtiz, illustrates the ways specific causal attributions affect people. It’s the middle of World War II, and the Nazis are beginning to move in on Casablanca, the largest city in Morocco, a place where refugees from Nazi rule often come to make their way to neutral Portugal and then perhaps the United States. We meet the expatriate American Rick Blaine (Humphrey Bogart), the seemingly self-

As the movie progresses, Rick learns that Ilsa thought that her husband, Victor, had died trying to escape a concentration camp, but found out that day in Paris that he was ill but alive and went to meet him. As Rick shifts his causal attribution for her not meeting him, his cynicism gradually lifts, and he ends up trying to help Victor escape. He arranges a meeting with his friend, the corrupt chief of police, Captain Louis Renault (Claude Rains), ostensibly to have Victor captured so he can have Ilsa for himself, a causal attribution quite plausible to Renault because of his own manipulative, womanizing ways. But Rick has a different reason for calling Renault to his café: to force him to arrange transport out of Casablanca for Victor. In case you haven’t seen the film, we won’t tell you how things turn out.

The film illustrates the importance of causal attributions not only in altering Rick’s outlook on life but in other ways as well. Major Heinrich Strasser of the Gestapo suspiciously interrogates Rick, asking him why he came to Casablanca. Rick offers an external attribution : “I came to Casablanca for the waters.” Strasser points out that there are no waters in Casablanca. Rick replies, “I was misinformed,” thus hiding his true attribution—

Maybe there was a special circumstance when Reese saw the movie that led her to love it. So if she saw it a second time and didn’t like it much, Kelley would label the outcome low in consistency, and you would probably conclude there was something unique about the first time she saw it that caused her reaction. Maybe she is ultrasensitive to variations in popcorn flavoring, and there was a delectable extra dash of butter and salt on her popcorn. This would be an attribution to an unstable factor that might be very different each time Reese saw the movie. However, if Reese saw the movie three times and loved it each time, Kelley would label the outcome high in consistency across time, and you would then be likely to entertain either a stable internal attribution to something about Reese, or a stable external attribution to something about the movie. Two additional kinds of information would help you decide.

Many people now discount Barry Bonds’s home-

[Doug Pensinger/Getty Images]

135

First, you could consider Reese’s typical reaction to other movies. If Reese always loves movies in general, or always loves boxing movies or Sly Stallone movies, then her reaction to Rocky 9 is low in distinctiveness. This information would lead you to an internal attribution to something about Reese’s taste in these kinds of movies rather than the quality of the movie. On the other hand, if Reese rarely likes movies, or rarely likes boxing or Stallone movies, then her reaction is high in distinctiveness, which would lead you more toward an external attribution to the movie.

Finally, how did other people react to the movie? If most others also loved the movie, there is high consensus, suggesting that something about the movie was responsible for Reese’s reaction. However, if most other people didn’t like the movie, you would be most likely to attribute Reese’s reaction to something about her. In short, when a behavior is high in consistency, distinctiveness, and consensus, the attribution tends to be external, whereas when a behavior is high in consistency but low in distinctiveness and consensus, an internal attribution is more likely. Research has generally supported Kelley’s model, although people often don’t seek all three types of information, and they more reliably use distinctiveness information than consensus information (e.g., McArthur, 1972).

The presence of other potential causes also can influence the weight that we assign to a particular causal factor. For example, not too long ago, most of the baseball-

Discounting principle

The tendency to reduce the importance of any potential cause of another’s behavior to the extent that other potential causes exist.

136

Motivational Bias in Attribution

What makes causal attributions so intriguing to social psychologists—

SOCIAL PSYCH out in the WORLD

“Magical” Attributions

“Magical” Attributions

Imagine that it is time for U.S. citizens to choose another president. Zach is at home on election night, watching as news channels tally up the votes from each state. He hopes and wishes and prays for his preferred candidate to emerge the victor. A couple hours later, Zach’s preferred candidate is declared the president-

This is an example of magical thinking—believing that simply having thoughts about an event before it occurs can influence that event. Magical thinking is a type of attribution. It’s a way of explaining what caused an event to happen. But it’s a special type of attribution because it goes beyond our modern, scientific understanding of causation. Returning to our example, we know that the election outcome is determined by myriad factors that are external to Zach, and not by his wishes transmitting signals to election headquarters. And yet, however unrealistic or irrational magical thinking is, many of us have an undeniable intuition that we can influence outcomes with just our minds. To see this for yourself, try saying out loud that you wish someone close to you contracts a life-

Magical thinking

The tendency to believe that simply having thoughts about an event before it occurs can influence that event.

Why is magical thinking so common? Freud (1913/1950) proposed that small children develop this belief because their thoughts often do in fact seem to produce what they want. If a young child is hungry, she will think of food and perhaps cry. Behold! The parent will often provide that food. Although as we mature, we become more rational about causation, vestiges remain of this early sense that our thoughts affect outcomes. As a result, even adults often falsely believe they control aspects of the environment and the world external to the self. Ellen Langer’s classic research on the illusion of control demonstrated that people have an inflated sense of their ability to control random or chance outcomes, such as lotteries and guessing games (Langer, 1975). For example, participants given the opportunity to choose a lottery ticket believed they had a greater chance of winning than participants assigned a lottery ticket.

Research by Emily Pronin and her colleagues have pushed this phenomenon even further (Pronin et al., 2006). In one study, people induced to think encouraging thoughts about a peer’s performance in a basketball shooting task (“You can do it, Justin!”) felt a degree of responsibility for that peer’s success. In another study, people asked to harbor evil thoughts about someone—

Magical thinking is not only something that individuals do. We see the same type of causal reasoning in popular cultural practices. In religious rituals such as prayer or the observance of a taboo, or when people convene to pray for someone’s benefit or downfall, there is the belief that thoughts by themselves can bring about physical changes in the world. Keep in mind, though, that a firm distinction between these forms of magical thinking and rational scientific ideas about causation may be peculiar to Western cultural contexts. Some cultures, such as the Aguaruna of Peru, see magic as merely a type of technology, no more supernatural than the use of physical tools (Brown, 1986; Horton, 1967). But people in Western cultures are not really all that different. Many highly popular self-

Although magical thinking stems partly from our inflated sense of control, it can also be a motivated phenomenon—

And if we did, it would probably tell us that the behavior was caused by a complex interaction of internal and external factors. For instance, any performance on a test is likely to be determined by a combination of the individual’s inherent aptitude, physical and mental health, amount of studying prior to the test, and other events in the person’s life commanding attention, as well as the particular questions on the test, the amount of time allotted for each question, and the quality of instruction in the course. And yet we typically either jump on the most salient attribution, or do a little thinking and information gathering, and then pick a single attribution, or at most two contributing factors, discounting other possibilities (Kelley, 1967).

137

As Heider (1958) observed, because causal attributions are often derived from complex and ambiguous circumstances, there is plenty of leeway for them to be influenced by motivations other than a desire for an accurate depiction of causality. Often the intention is to preserve positive images of those we like and negative views of those we dislike. We are likely to attribute a friend’s success to the friend’s good qualities; if an enemy does well, we’re likely to attribute it to dumb luck or cheating. Similarly, people generally believe that their country’s foreign policies are motivated by noble goals such as spreading freedom and prosperity rather than ignoble goals such as greed and revenge.

If we just want closure, we grab the simplest, most readily available attribution. One explanation of the FAE is that we want to attribute people’s behavior to stable traits so we can feel that we’ll be able to predict their behavior in the future (Gilbert & Malone, 1995). In fact, people attribute the behavior of another person more to that individual’s personality than to some other cause if they expect to have to interact with that person in the future (e.g., Miller et al., 1978). If we can believe we know what others are like, we will be more confident that we can get what we want from them.

Our attributions are also biased by our preferred views of the way the world works—

138

|

People tend to explain events in terms of particular causes, referred to as causal attributions. |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Dimensions of Causal Attributions Locus of causality refers to whether attributions are made to an internal attribute of the actor or to some external factor in the person’s environment. Stability refers to whether a causal factor is presumed to be changeable or fixed. People who believe that attributes can change are more likely to seek opportunities to improve in areas related to that attribute. |

Fundamental Attribution Error We tend to attribute the behavior of others to internal qualities. We generally attribute our own behavior to the situation. Although the FAE occurs across different cultures, collectivist cultures often emphasize situational factors more than individualistic cultures do. |

A Three- A behavior is observed and labeled. An internal attribution is made. Situational factors will be considered if there is a motivation for accuracy and if cognitive resources are available. |

Effort for Unexpected or Important Events When motivated, we make and test hypotheses for causes of the event. We consider the consistency, distinctiveness, and consensus information regarding the event. Motivational biases can lead us to adjust our attributions to support our own preferred beliefs. |