4.3 Forming Impressions of People

Let’s return to the scene of the accident with which we began this chapter. As the investigator, you show up and see the two cars in the intersection and the two drivers engaged in animated debate about who was at fault. Very quickly you’ll begin to form impressions of each of them. What are the factors that influence the perceptions of the drivers that you’ll form? Perhaps it’s their appearance and manner of dress, the ethnic group(s) they apparently are members of, or even your first glimpse of their demeanor. Obviously the causal attribution processes we just explored will strongly affect the way in which you perceive them, but much of the time we do not engage in this kind of extensive thought. Instead, we use a variety of other processes to form an impression of each driver. We have already seen in chapter 3 that we humans have an elaborate psychological toolbox for making sense of others, one that includes schemas and metaphors. In this section, we examine some of the more specific processes that guide our perception.

Beginning With the Basics: Perceiving Faces, Physical Attributes, and Group Membership

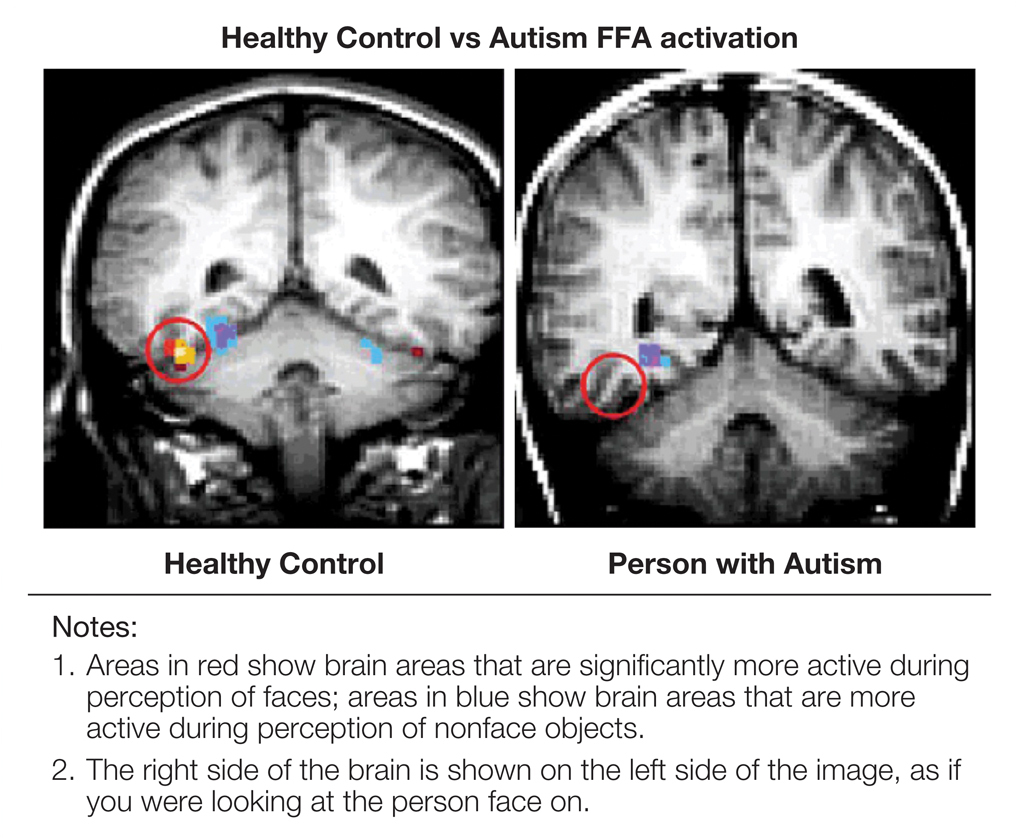

FIGURE 4.7

Autism and Social Perception

The fusiform face area (FFA) underlies our ability to recognize people, an ability that is somewhat impaired in those who are autistic.

When we encounter another person, one of the first things we recognize is whether that person is someone we already know or a total stranger. At first glance, it might seem that we identify other people in the same way that we recognize any kind of familiar object, such as our car, our house, or our dog. But there is something unique about perceiving people. As we mentioned in chapter 2, a region in the temporal lobe of the brain called the fusiform face area (FFA) helps us recognize the people we know (Kanwisher et al., 1997). The essential role of the fusiform face area has been made clear from studies of people who suffer damage to this neural region of the brain. Such individuals suffer from prosopagnosia, the inability to recognize familiar faces, even though they are quite capable of identifying other familiar objects. It seems that the ability to recognize the people we know was so important to human evolution that our brains have a region specifically devoted to this task. Research is beginning to suggest that those with autism show less activation in this brain region, consistent with the notion that autism impairs social perception (FIGURE 4.7) (Schultz, 2005).

Fusiform face area

A region in the temporal lobe of the brain that helps us recognize the people we know.

Prosopagnosia

The inability to recognize familiar faces.

139

Think ABOUT

Our brains are also highly attuned to certain physical characteristics of other people. In our daily interactions, we might use a range of observable characteristics to form judgments about other people, from their hair color and dress to the bumper stickers on their car. But some characteristics are perceived and interpreted so quickly, and become so integral to the impression of another person, that researchers have proposed that we have innate systems designed to detect them (Messick & Mackie, 1989). These include a person’s age and sex and whether we are related to him or her (Lieberman et al., 2008). Think about the last time you bought a cup a coffee or went through the grocery-

People may have evolved to detect these cues automatically because they are useful for efficiently distinguishing allies from enemies, potential mates, and close relatives (Kurzban et al., 2001). Our ability to recognize these characteristics quickly makes sense from the evolutionary perspective. The idea is that to survive, our ancestors had to avoid dangerous conflicts with others and to avoid infection from people who were carrying disease. Those individuals who could quickly size up another person’s age, sex, and other physical indicators of health, strength, and similarity most likely had better success in surviving and reproducing than those who made these judgments less quickly or accurately. For example, recent work suggests that merely viewing pictures of people who are sick triggers physiological reactions designed to cue the immune system to prepare to fend off potential disease (Schaller et al., 2010).

140

Because we are a highly social species, our ability to survive and thrive has depended not just on avoiding disease but even more on our ability to successfully coordinate behaviors within our social groups, whether they are families, tribes, clubs, or communities. As a result, we tend immediately to recognize features of other people that indicate that they are likely to be cooperative group members or, alternatively, to pose a threat to our group functioning. Of course, that doesn’t mean that such judgments are correct, especially as they pertain to our functioning in the modern world, only that the brain may have evolved to make such judgments automatically.

Impression Formation

Think back to when you first arrived at college. You moved into your new dorm or apartment and met the person with whom you would be sharing your living space for the next nine months. You were probably thinking, Who is this person? What will he or she be like as a roommate? Once we have made an initial determination of a person’s basic characteristics, such as gender, the next step in person perception is to form an impression of that person’s personality. What traits, preferences, and beliefs make your roommate the unique person he or she is? Knowing what people are like is useful because it guides how you act toward them. If you think someone is likely to be friendly, you might be more likely to smile at him or her and act friendly yourself, whereas if you think someone is likely to be hostile, you might avoid him or her altogether.

How do we form impressions of others? There are generally two ways: one from the bottom up, the other from the top down. Let’s look at each in detail.

Building an Impression from the Bottom Up: Decoding the Behaviors and Minds of Others

We build an impression from the bottom up when we watch what a person does and says, then, on the basis of those observations, form an impression in our minds of who the person is. We call this building from the bottom up because we gather individual observations of a person to form an overall impression of who that person is. To grasp this concept, imagine that a friend takes a trip to a city you’ve never been to, and she posts new pictures of the city every day on Facebook. Even though you have no prior knowledge of that city, by looking at these pictures you would eventually build up an impression of the city—

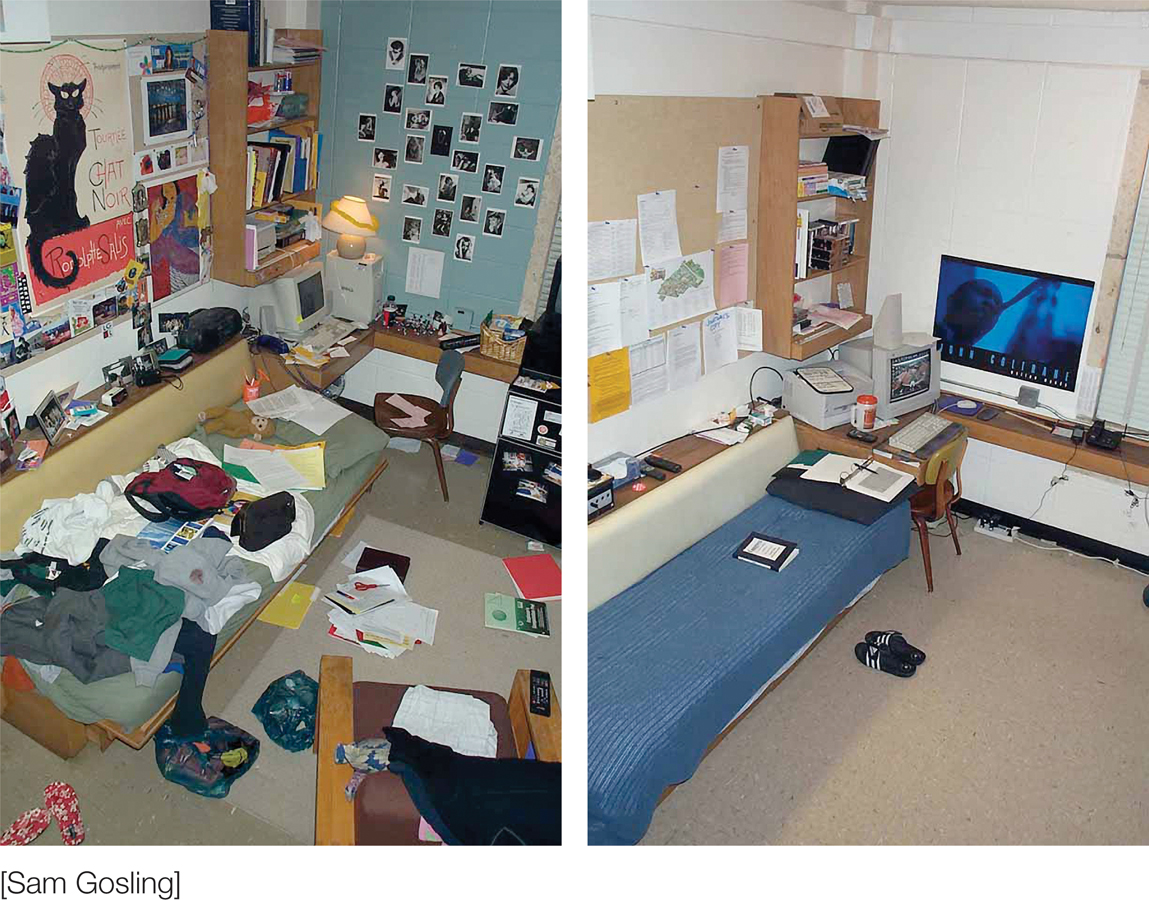

FIGURE 4.8

Clues to Personality

What’s your impression of the person who lives in the room on the left? What about the person living in the room on the right? Think about how you make these judgments without even seeing or knowing the person.

[Sam Gosling]

Brief Encounters: Impressions from Thin Slices

We are quite accurate at forming impressions of individuals by observing what they say and do. In fact, we can often decode certain personality characteristics based on very thin slices of a person’s behavior. A meta-

In fact, people can accurately perceive the personality traits of others without ever seeing or meeting them, having only evidence of everyday behaviors, such as how they decorate their dorm rooms, what they post on Facebook, or the music they listen to (Gosling et al., 2002; Rentfrow & Gosling, 2006; Vazire & Gosling, 2004). Some personality traits, such as conscientiousness and openness to new experiences, can be accurately perceived merely by seeing people’s office space or bedrooms (Gosling et al., 2002). Check out the exercise in FIGURE 4.8 to get a sense of what we mean.

141

Likewise, when college students were randomly paired and given time to get to know one another, music was one of the most discussed topics of conversation, and such discussions helped them form accurate judgments of each other’s personality (Rentfrow & Gosling, 2006). For example, a preference for music with vocals was found to be diagnostic of someone who is socially extraverted.

Theory of Mind

Not only can we learn about a person’s personality on the basis of minimal information but we are also pretty good at reading peoples’ minds. No, we are not telepathic. But we do have an evolved propensity to develop a theory of mind—a set of ideas about other people’s thoughts, desires, feelings, and intentions, given what we know about them and the situation they are in (Malle & Hodges, 2005). This capacity is highly valuable for understanding and predicting how people will behave, which helps us cooperate effectively with some people, compete against rivals, and avoid those who might want to do us harm.

Theory of mind

A set of ideas about other peoples’ thoughts, desires, feelings, and intentions based on what we know about them and the situation they are in.

For example, we use others’ facial expressions and tone of voice to make inferences about how they are feeling. If your new roommate comes home with knit eyebrows, pursed lips, clenched fists, and a low and tight voice, you might reasonably assume that your roommate is angry about something. Most children develop a theory of mind around the age of four (Cadinu & Kiesner, 2000). We know this because children around this age figure out that their own beliefs and desires are separate from others’ beliefs and desires. (Before that, they assume that if they know something, everyone else knows it as well.) However, people with certain disorders, such as autism, never develop the ability to judge accurately what others might be thinking (Baron-

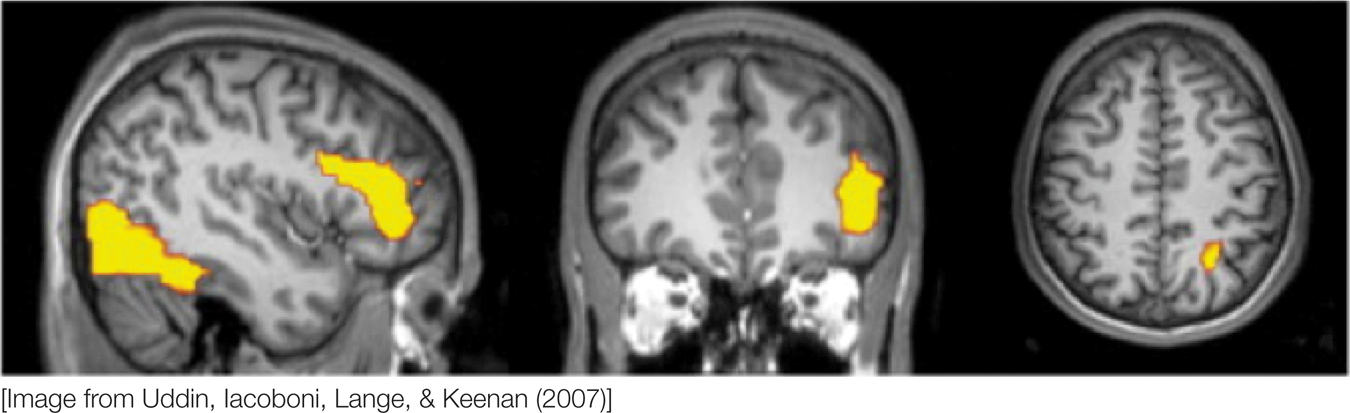

Research has begun to uncover the brain regions involved in this kind of mindreading. Neuroscientists have focused on a brain region labeled the medial prefrontal cortex (Frith & Frith, 1999). Some researchers believe that this region contains mirror neurons, which respond very similarly both when one does an action oneself and when one simply observes another person perform that same action (FIGURE 4.9) (Uddin et al., 2007). When seeing your roommate’s expressions of anger as described above, you might have found yourself imitating these same facial displays. But even if your own facial expression didn’t change, mirror neurons in your brain were firing that allowed you to simulate your roommate’s emotional state, helping you to understand what your roomate is thinking and feeling (Iacoboni, 2009).

Mirror neurons

Certain neurons that are activated both when one performs an action oneself and when one simply observes another person perform that action.

FIGURE 4.9

Mirror Neurons

Mirror neurons in the frontal parietal regions of the right hemisphere are activated both when we think about ourselves and when we think about or observe others. Researchers speculate that these mirror neurons underlie our ability to imagine what others are thinking and feeling.

[Image from Uddin, Iacoboni, Lange, & Keenan (2007)]

142

Building an Impression from the Top Down: Perceiving Others Through Schemas

Bottom-

Transference

We often automatically perceive certain basic characteristics about a person and then infer that that individual will share the features that we associate with other people like him or her. Sometimes this quick inference might result from the person’s reminding us of another person we already know. Let’s suppose your roommate arrives at the dorm and your first thought is that she bears some resemblance to your favorite cousin. Research by Susan Andersen and colleagues (Andersen et al., 1996) suggests that because of this perceived similarity, you might be more likely to assume that your roommate’s resemblance to your cousin lies not just in appearance but extends to her personality as well. This process was first identified by Freud (1912/1958) and labeled transference. Transference is a complex process in psychoanalytic theory, but in the context of social psychological research it has been more narrowly defined as forming an impression of and feelings for an unfamiliar person using the schema one has for a familiar person who resembles him or her in some way.

Transference

A process whereby we activate schemas of a person we know and use the schemas to form an impression of someone new.

If you meet someone who reminds you of Will Smith, you’re likely to transfer some of your feelings about this famous actor to the new person.

[Photo by Petroff/Dufour/Getty Images]

Andersen and her collaborators (1996) tested this process in one experiment by having participants first describe the characteristics of two people who they knew well, one whom they liked and one whom they disliked. Two weeks later, these same participants arrived at what they thought was a completely unrelated study of impression formation. Participants were asked to form an impression of a stranger with whom they would later be partnered only on the basis of a list of attributes that the person had used to describe him-

False Consensus

Even when a person we meet doesn’t remind us of someone specific, we often project onto him or her those attitudes and opinions of the person we know the best—

False consensus

A general tendency to assume that other people share our own attitudes, opinions, and preferences.

143

False consensus stems from a number of processes (Marks & Miller, 1987). For one, our own opinions and behaviors are what are most salient to us and therefore most cognitively accessible. So they are most likely to come to mind when we consider what other people think and do. Second, false consensus can be amplified by motivated processes. It is validating for our worldview and self-

Finally, we might also fall prey to false consensus because we tend to like and associate with people who are in fact similar to us. We’ll get into this “birds of a feather flocking together” idea more in chapter 14. If our group of friends really do like to smoke and drink, then in our own narrow slice of the world, it does seem as if everyone does it, because we forget to adjust for the fact that the people we affiliate with are not very representative of the population at large. In the present day, we see this happening on the Internet, where our group of Facebook friends or Twitter followers might only seem to validate and share our opinions, and the news outlets we seek out package news stories in ways that seem to confirm what we already believe. One of the benefits of having a diverse group of friends and acquaintances and a breadth of media exposure might be to disabuse us of our false consensus tendencies.

Implicit Personality Theories

As Heider (1958) suggested, we are all intuitive psychologists trying to make sense of people’s behavior on a daily basis. With two or more decades of practice under our belt, we develop our own theories about how different traits are related to each other. Consequently, one way we use our preexisting schemas to form impressions of a person is to rely on our implicit personality theories. These are theories that we have about which traits go together and how they combine.

Asch (1946) found that people tend to combine traits in a way that forms a coherent overall depiction of a person, even when some of the traits seem to be contradictory. For example, a sociable, lonely person might be viewed as someone with lots of superficial acquaintances but no close relationships (Asch & Zukier, 1984). Asch also found that some traits are more central than others, and the more central traits affect our interpretation of other traits that we attribute to a person. Think about a guy named Bob who is described as “intelligent, skillful, industrious, warm, determined, practical, and cautious.” Asch’s participants viewed someone like Bob as generous, wise, happy, sociable, popular, and altruistic. Now imagine a guy named Jason, described as “intelligent, skillful, industrious, cold, determined, practical, and cautious.” Asch’s participants viewed someone like Jason as ungenerous, shrewd, unhappy, unsociable, irritable, and hard headed.

The only difference in the descriptions of the two guys was that warm was included in the list of traits for Bob and was replaced with cold for Jason. Yet changing that one trait—

144

Another implicit personality theory is that similar traits go together. Having already decided that your roommate is neat and organized, you might also infer that your roommate will be a conscientious student, one who always attends class, takes clear notes, and studies hard. Such a theory seems reasonable. Why shouldn’t a person who is conscientious with living habits also be conscientious with schoolwork?

Although as social perceivers we make such assumptions all the time, in fact, people often are more complicated than we realize. One study made repeated observations of conscientious behaviors in a sample of college students (Mischel & Peake, 1982). Measured behaviors included class attendance, assignment neatness, and neatness in students’ dorm rooms. Peers and parents also rated the conscientiousness of these students. Interestingly, the raters tended to agree with each other about how conscientious a given person was, even though the person’s own conscientious behaviors were uncorrelated across different situations. In other words, your roommate’s closest friends and relatives might, like you, assume that your roommate’s conscientiousness in the dorm will be reflected in conscientiousness in the classroom, but the two types of behaviors might in fact be unrelated. Rather, each of you might be relying on the same implicit personality theory to make your judgment.

This example concerning conscientiousness is an implicit personality theory about semantically similar traits being correlated with each other (tidy = organized = prompt). Another type of implicit personality theory assumes that traits of the same positive or negative type tend to go together. For example, people who are more attractive are also perceived to be more personable, happier, and more successful, a finding that has come to be known as the “what is beautiful is good” stereotype (Dion et al., 1972). But this effect is most likely reflective of a broader halo effect (Thorndike, 1920; Nisbett & Wilson, 1977a), whereby social perceivers’ assessments of an individual on a given trait are biased by their more general impression of the individual. If the general impression is good, then any individual assessment of the person on friendliness, attractiveness, intelligence, and so on, is likely to be more positive. The same halo effect negatively biases our perceptions of the people we dislike. If you’ve had a strong negative reaction to your neatnik of a roommate, you might start forming assumptions that your roommate will possess many other negative qualities that will bolster your impression. Wouldn’t life be simpler if people either had all good qualities or all bad ones?

Halo effect

The tendency of social perceivers’ assessments of an individual on a given trait to be biased by the perceivers’ more general impression of the individual.

Stereotyping

The process just described involves applying a schema that we have of a type of person, “attractive people,” to judge an individual whom we initially have categorized as being attractive. This is what we do when we stereotype others. Stereotyping is a cognitive shortcut or heuristic, a quick and easy way to get an idea of what a person might be like. Think about when you learn that your new roommate is a political science major planning for a future career in politics. Might you use whatever prior schema you have about politicians to make a judgment of what she is like as a person? Some of those impressions might later prove to be accurate (e.g., an abiding interest in current events), others might not (e.g., a knack for talking eloquently without saying anything of substance), but in both cases, they helped you size up your new living partner quickly.

We will go into much greater depth regarding the processes underlying stereotyping and its consequences for social prejudices and intergroup conflict in chapter 11. For now, we want to underscore the point that stereotyping is an application of schematic processing. Forming a completely accurate and individualized impression of a person (i.e., one that is unbiased by stereotypes) is an effortful process. We often fall back on mental shortcuts when the stakes are low (“Does it really matter if I falsely assume that Tom is an engineer?”) or we aren’t especially motivated to be accurate. But even when the stakes are high and our judgments matter, we can still be biased by our stereotypes when we are tired or fatigued. For example, when participants are asked to judge the guilt or innocence of a defendant on the basis of ambiguous evidence, their decisions are more likely to be biased in stereotypical ways when they are in the off-

145

Is this your stereotypical billionaire? Mark Zuckerberg, the cofounder and CEO of Facebook, is estimated to be worth over $30 billion.

[AP Photo/Paul Sakuma]

In this way, general stereotypes about a group of people are often employed to form an impression of individual members of that group. In addition, sometimes we take a bit of information we might know about a person and erroneously assume that that person is part of a larger category merely because he or she seems to map onto your schema of that category. For example, imagine you’ve been given the following description of a person chosen from a pool of 100 professionals:

Jack is a 45-

If this is all you knew about Jack, do you think it’s more likely that Jack is an engineer or a lawyer? If you are like most of the participants who were faced with this judgment in a study carried out in 1973, you’d stake your bet on engineer. But what if you were also told that of the 100 professionals, 70 are lawyers and 30 are engineers? Would that make you less likely to guess engineer? According to research by Amos Tversky and the Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman (1973), the answer is no. As long as the description seems more representative of an engineer than a lawyer, participants guess engineer regardless of whether the person was picked out of a pool of 70% lawyers or 70% engineers!

This is because people fall prey to what Kahneman and Tversky called the representativeness heuristic, a tendency to overestimate the likelihood that a target is part of a larger category if it has features that seem representative of that category. In this case, “lacking interest in political issues and enjoying mathematical puzzles” seems more representative of an engineer than of a lawyer. But this conclusion depends heavily on the validity of these stereotypes and involves ignoring statistical evidence regarding the relative frequency of particular events or types of people. Even when the statistical evidence showed that far more people in the pool were lawyers than engineers (that is, a 70% base rate of lawyers), the pull of the heuristic was sufficiently powerful to override this information. Although the representativeness heuristic applies to much more than just social perception, it is part of the reason stereotypes are so sticky—

Representativeness heuristic

The tendency to overestimate the likelihood that a target is part of a larger category if it has features that seem representative of that category.

Changing First Impressions

No doubt you have heard the old adage that you have only one chance to make a first impression. The research reviewed above suggests that we do form impressions of others quite quickly. As we’ve already seen, once we form a schema, it becomes very resistant to change and tends to lead us to assimilate new information into what we already believe. What we learn early on seems to color how we judge subsequent information. This primacy effect was first studied by Asch (1946) in another of his simple but elegant experiments on how people form impressions. In this study, Asch gave participants information about a person named John. In one condition, John was described as “intelligent, industrious, impulsive, critical, stubborn, and envious.” In a second condition, he was described as “envious, stubborn, critical, impulsive, industrious, and intelligent.” Even though participants in the two conditions were given the same exact traits to read, the order of those traits had an effect on their global evaluations of John. They rated him more positively if they were given the first order, presumably because the opening trait of “intelligent” led people to put a more positive spin on all of the traits that followed it. When it comes to making a good impression, you really do want to put your best foot forward.

Primacy effect

The idea that what we learn early colors how we judge subsequent information.

146

But if we do form such quick judgments of people, what happens if we later encounter information that disconfirms those initial impressions? There is some suggestion that our initial impressions can be changed. Recall our earlier discussion of memory for information that is highly inconsistent with a preexisting schema. In fact, when people do things that are unexpected, our brain signals that something unusual and potentially important has just happened (Bartholow et al., 2001). A broad network of brain areas appears to be involved in this signaling process, spurred by the release of the neurotransmitter norepinephrine in the locus coeruleus (Nieuwenhuis et al., 2005). Because of this increased processing of information, we are usually better at remembering highly unexpected information about a person (Hastie & Kumar, 1979). However, this seems to be particularly true when someone we expect good things from does something bad.

Negativity Bias

Research suggests that we are particularly sensitive to detecting the negative things in our environment (Ito et al., 1998). Life in both the physical and social world is fraught with danger; consequently, our capacity to live long and prosper depends on heightened vigilance against potential threats. Neglecting to notice a beneficial person or event can cost us valuable resources but is unlikely to cause irreparable harm, but failing to attend to a dangerous person or event can be lethal. Thus, the process of evolution seems to have biased us toward attending most carefully to negative information, which may help explain rubbernecking when we see car accidents and the popularity of violence in entertainment. It also may explain why negative information weighs more heavily in our impressions of other people than does positive information (Pratto & John, 1991).

This doesn’t mean that we are inclined to see the worst in others; it simply means that when we do encounter people doing bad things, it’s pretty useful to pay attention to it and factor it into our impressions. Most of the time, people follow the norms and conventions of good behavior, so bad behaviors might seem more surprising because they are relatively rarer. But they also seem more diagnostic of who a person is, given that person’s apparent willingness to shirk social norms that keep most people from engaging in such bad behavior. As a consequence, we are particularly likely to remember when someone we thought was good does a bad thing, but we easily ignore and forget when people we expect bad things from do something good (Bartholow et al., 2003; Bartholow, 2010).

Stereotypes and Individuation

In addition to salient and unexpected negative behavior, impressions may also change as we get to know a person and view him or her more as an individual than as a member of a stereotyped group. When do people rely on the top-

Because it takes more mental energy to process inconsistent or unexpected information (Bartholow et al., 2003), we tend to truly perceive a person as an individual unique from his or her social groups only when we are motivated to understand who that person is (Fiske & Neuberg, 1990). This might happen when we need to work together on a project (Neuberg & Fiske, 1987) or are made to feel similar to them is some way (Galinsky & Moskowitz, 2000). Otherwise, we lazily apply the schemas we have about a group to make a quick judgment about the individual. However, as we learn new information, we might set aside those stereotypes to pay more attention to the person (Kunda et al., 2002). Learning more information about a person’s individual experience can reduce our reliance on our stereotypes to understand who he or she is.

|

Forming Impressions of People |

147

|

As social beings, we are highly attuned to other people. |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

The Basics A region in the temporal lobe, the fusiform face area, helps us recognize faces. We have evolved to quickly size up physical indicators of health, strength, and similarity, perhaps for survival reasons. |

Decoding Minds and Behavior We build an impression from the bottom up when we gather individual observations of a person’s actions to draw an inference about who he or she is. Our impressions are often quite accurate, even with minimal information. We are also pretty good at understanding what people are thinking. |

Perceiving Through Schemas We build an impression from the top down when we use a preexisting schema to form an impression of another. These preexisting schemas are often heuristics that include transferring an impression we have of one person to another, assuming that similar traits go together, and relying on stereotypes. Such heuristics can lead us to make biased judgments. |

Changing First Impressions Initial impressions can change when people act in unexpected ways. We are more likely to change an initially positive impression of someone when he or she does negative things than we are to change an initially negative impression when the person does positive things. |