7.3 Conformity

Conformity is a phenomenon in which a given individual alters her beliefs, attitudes, or behavior to bring them in accordance with the behavior of others. Muzafer Sherif (1936) sought to study the possibility that even basic perceptions of events can be affected by efforts to bring one’s own perceptions in line with those of others. To do so, he took advantage of a perceptual illusion first noted by astronomers. If a small, stationary point of light is shown in a pitch-

Conformity

The phenomenon whereby an individual alters his or her beliefs, attitudes, or behavior to bring them in accordance with those of a majority.

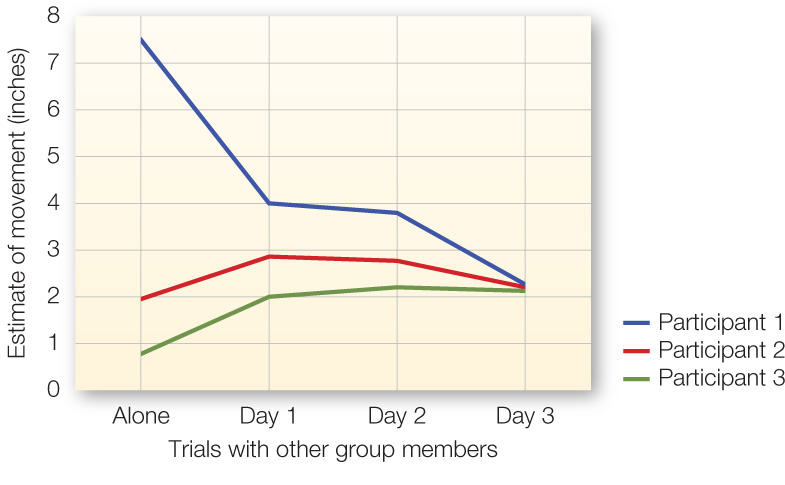

FIGURE 7.2

Sherif conformity studies on norm formation

The ambiguity of the estimation task reveals an informational influence on conformity and the formation of a group norm. When participants got into a group, their individual judgments converged to a common norm over the course of three days.

[Data from Sherif (1936).]

Sherif sought to determine if other people could influence an individual’s perceptions of how much the point of light moves. First, he had people individually judge how much the point of light moved. He got various estimates (see FIGURE 7.2). Then he put two or three people together in a dark room and had them call out estimates of how much the light was moving. He made the quite remarkable finding that people started out with varying estimates, but after only a few trials they came to agree on a particular estimate of how much the light moved. He also showed that if he planted a confederate in the group who made a particularly large assessment of the distance moved, that person could move the group norm to a higher estimate. Furthermore, Jacobs and Campbell (1961) showed that if the confederate was replaced by new, naïve participants, the remaining group members would sustain the group norm and bring the new participants on board with them. This “tradition” continued over five “generations” of participants.

240

Of course, it is reasonable to ask whether the participants’ agreed-

Public compliance

Conforming only outwardly to fit in with a group without changing private beliefs.

Private acceptance

Conforming by altering private beliefs as well as public behavior.

This body of research demonstrated conformity to a group norm on the basis of what is called informational influence. The participants were not just trying to get along; they were trying to figure out how much the light was moving and used other people’s estimates as information. Similar findings have been shown for a wide variety of tactile, perceptual, numerical, and aesthetic judgments (Sherif & Sherif, 1969). Generally, informational influence leads to private acceptance—

Informational influence

Occurs when we use others as a source of information about the world.

People most often seek such informational influence when they aren’t sure what to think or how to behave. This was clearly the case for the ambiguous task that Sherif gave his subjects. Judging how much a point of light moves in a dark room can be tricky, especially when it’s actually not moving at all! But would people be so influenced by others if the task being judged was less ambiguous? What if they could rely on their own senses to make a judgment? This is what Solomon Asch wanted to find out.

Asch Conformity Studies

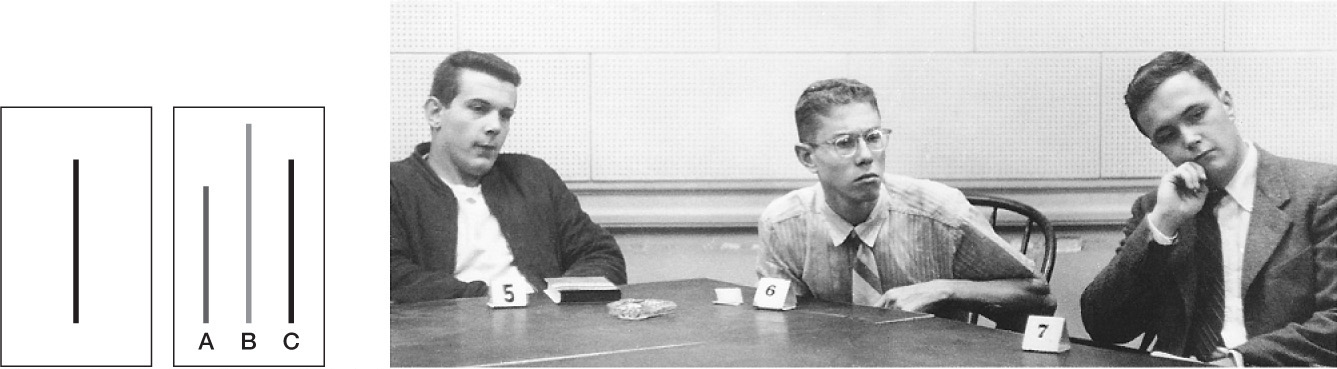

FIGURE 7.3

Asch conformity studies

The lack of ambiguity of the estimation task reveals a normative influence on conformity. Many participants went along with the group judgment even when their senses told them the judgment was incorrect.

[Photo: William Vandivert, Solomon E. Asch, “Opinions and Social Pressure,” Reproduced with permission. Copyright 1955 Scientific American, Inc. All rights reserved.]

Imagine that you show up to a classroom to participate in a psychology experiment on visual judgment. With you are seven other students. As you settle around a table, an experimenter explains that he will display a series of pairs of two large, white cards. On one card in each pair are three vertical lines of varying lengths labeled A, B, and C; the other card has a single vertical line (see FIGURE 7.3). Your task is to state out loud which line length best matches the single line. The first trial begins, and the experimenter starts with the first student to your left. The student says Line C. The next person also says Line C, and so forth, until it’s your turn to respond. You respond Line C and quickly settle in to what appears to be a super boring (and totally easy) experiment. After a few such trials, however, something unexpected occurs. On presentation of the lines like those displayed in FIGURE 7.3, the first student responds with Line A. You probably stifle a chuckle and think this person needs to have his eyes checked. But then the next person also says Line A. And so does the next and the person after that. All of the other seven students say Line A; you begin to think that maybe it is you who needs your eyes checked. What could be going on here? Now it is your turn. How do you think you would respond?

241

This is the situation students faced in one variant of Asch’s (1956) classic conformity studies. In contrast to Sherif, who presented people with an ambiguous situation, Asch was interested in how people would respond in situations where there was little ambiguity about what they perceived. Indeed, when judging these line lengths alone, participants made errors on less than 1% of the trials. Thus, Asch (1956) presented each participant with two opposing forces: on the one hand, the evidence of his senses, and on the other, the unanimous opinion of a group of his peers (who actually were confederates in the experiment and instructed to respond in a set manner). This situation enabled Asch to address the question, What would people do when their physical senses indicated an answer that was in conflict with the views of the majority? Would people go with the answer they knew was correct? Or would they deny their own perceptions to agree with the group? Asch discovered that in situations such as that just described, 75% conformed to the group opinion in at least one trial, and overall, participants conformed on 37% of the trials.

What the Asch Conformity Studies Teach Us About Why People Conform

Take a moment to think about what this study teaches us beyond what we learned from Sherif’s work. What did you come up with? If you started to think about why people conform, you’re in the right ballpark. Whereas Sherif’s studies show how our view of the world is shaped by information we get from other people, Asch’s studies point to a different—

Normative influence

Occurs when we use others to know how to fit in.

242

But the objecting reader might be thinking, “Wait a minute! How do you know that people in Asch’s study were not really convinced by the group? Maybe they did think the others were informing them about the actual lengths of the lines.” And indeed, in postexperimental interviews, Asch found that some participants did question their own perceptions and thought that the majority might be correct. Some questioned their viewing angle, others their eyesight. However, they were in the minority. The rest acknowledged that they made choices they didn’t believe were right simply to go along with the group.

When we stick out, we can risk ridicule and rejection from others.

[Joseph Farris/Cartoonstock]

To probe this issue further, Asch conducted a number of variants of this study. He found that when people did not have to give their responses in public but could instead write down their responses privately after hearing others’ judgments, they almost never went along with the group opinion. Thus, the power of having to give a public response played a pivotal role in participants’ tendency to conform. Asch’s postexperimental interviews revealed that many participants felt anxious, feared the disapproval of others, and went along with the group to avoid sticking out. When we stick out, we run the risk of looking foolish, and many people are reluctant to face that possibility (Cialdini & Goldstein, 2004).

Nonconformers may even risk social rejection and ostracism. A classic study by Stanley Schachter (1951) showed that when one confederate planted in a group stubbornly disagrees with the unanimous opinion of the group, that person is taunted, verbally attacked, and rejected. As we discussed in chapter 6, a substantial body of research shows that people find social rejection and ostracism highly upsetting. So the negative reaction that nonconformers so frequently receive helps to explain why people often submit to the norms of the group. Interestingly, Schachter also found that an initial nonconformer who subsequently steps in line is warmly received. After all, it is gratifying when someone who deviates from the rest of the group sees the light.

Although most participants in Asch’s studies publicly adjusted their responses to support the group perception at least once, it was not necessarily the case that all, or even most, were blindly punting away their own individualism to succumb submissively to the group opinion. Asch recognized this as well, noting that in postexperimental interviews many subjects expressed considerable concern for the solidarity and well-

What Personality and Situational Variables Influence Conformity?

Despite this more positive view of conformity, in many contexts, such as deciding if a defendant is guilty or if an aircraft design is safe, it would be rather alarming if individuals went along with the group despite what they know to be true from their physical perceptions. From Asch’s studies, it’s tempting to agree with Mark Twain, who noted, “We are discreet sheep; we wait to see how the drove is going, and then go with the drove.” But we shouldn’t lose sight of the fact that 25% of participants never conformed to the group. These results also provide compelling evidence that some people do resist social pressure.

243

Unfortunately, not a great deal is known about the personality characteristics of those who tend to conform as opposed to those who do not. Early studies found some indications that people who have such traits as a high need to achieve (McClelland et al., 1953) and a propensity to be leaders (Crutchfield, 1955) are less likely to conform. People who have a greater awareness of self and high self-

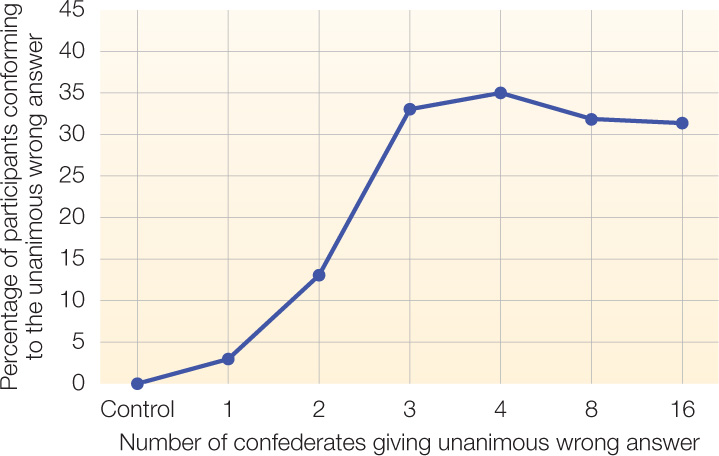

FIGURE 7.4

The effect of group size on conformity

Conformity is more likely as group size increases from 1 to 3 people, but then the influence starts to level off.

[Data from Asch (1956).]

For years, psychologists also thought that women conformed more than men, but any such differences are actually quite small. It turns out that people will more readily conform on topics they don’t know much about. Thus, whereas women are more likely to conform on stereotypically masculine judgments on topics such as sports or cars, men are more likely to conform on stereotypically feminine judgments on topics such as fashion or family planning (Eagly & Carli, 1981).

It’s a bird, it’s a plane, it’s…. When we see others gazing upwards, we’re likely to follow suit. Here people on the streets of Ajmer in India demonstrate this tendency.

[Getty Images/Lonely Planet Images]

In addition to self-

Participants were more likely to conform when three confederates gave unanimous wrong answers than when two confederates gave unanimous wrong answers. Interestingly, however, further increases in majority size above three did not lead to significantly more conformity. It appears, then, that a majority of three is quite influential.

This effect of diminishing returns for group size also is apparent with more subtle instances of conformity. Imagine walking down the street and seeing someone looking up and maybe even pointing at the sky. It’s an almost reflexive response to follow that person’s gaze to see what might be so interesting. Stanley Milgram and colleagues (1969) carried out a classic study to capture this simple phenomenon. On Forty-

244

More important than the number of others is their unanimity. Even one dissenting voice in a group of nine confederates appears to disrupt the pressure of the majority view and decreases conformity such that participants conform to the group on less than 5% of the trials in the line-

The study of passersby looking up by Milgram and colleagues (1969) also is interesting because it highlights the often reflexive nature of conformity. Although the people unwittingly participating in the study might briefly have had the conscious thought, “I wonder what’s going on,” it’s also likely that they were already following the gaze of the others even as this thought was still forming in their heads. Some instances of conformity do not involve deliberative thought but rather are responsive to social cues that may influence us without our awareness (Eply & Gilovich, 1999).

Another variable that contributes to conformity is the extent to which the individual identifies with the majority. When the individual strongly identifies with the larger group, that group, known as a reference group, is likely to have a substantial influence on the individual’s attitudes and behavior (Turner, 1991). Reference groups are generally a source of both informational and normative influence. We trust them more than other groups, and we want their approval more. Theodore Newcomb (1943) conducted a unique longitudinal study of conformity by tracking the political and economic attitudes of new students who enrolled in Bennington College, a private college for women, back in the 1930s. The students came from wealthy, conservative backgrounds, but the staff and senior students at the college were quite liberal. He found that most of the students became increasingly liberal over their years at the college. Furthermore, a follow-

Reference group

A group with which an individual strongly identifies.

An interesting finding was that a minority of the young women who did not become very socially involved on campus retained their conservative attitudes throughout college. Newcomb discerned that the difference was that the young women who became liberal used the campus community as a reference group, whereas the young women who remained conservative maintained their families and friends from home as their reference group.

Neural Processes Associated With Conformity

Recent research using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) of the brain provides some insight into the neural processes that may be associated with conformity. As we noted earlier, Sherif’s work suggests that a majority group opinion sometimes changes the way we actually perceive stimuli in our environment. Are these changes in perception reflected in how our brain processes perceptual stimuli? It appears so. Berns and colleagues (2005) scanned participants’ brains while they made judgments about the spatial orientation of three-

245

Berns and colleagues also provided evidence about how the brain responds when we do go against the grain, fail to conform, and thus stick out. Specifically, when participants did not conform to group opinion, brain scans of the nonconformists showed increased activation of the amygdala in the brain’s right hemisphere, an area commonly associated with fear. This study fits findings concerning rejection of deviants and the negative feelings such rejection and ostracism arouse in them, suggesting that people may conform as a way to avoid these negative feelings (Cialdini & Goldstein, 2004).

The neuroscience perspective has guided research suggesting that conformity may occur in part because people view going against the group as akin to making a mistake. In a study conducted in the Netherlands, Klucharev and colleagues (2009) had participants make judgments about how attractive they found pictures of people’s faces while their brains were being scanned. After each rating, participants were informed of the average European rating of each face. About a half hour after this, participants were unexpectedly asked to re-

|

Conformity |

| People conform both to get along with others and because others are a source of information. | ||

|---|---|---|

|

The Sherif and Asch conformity studies People often conform to groups. |

Personality and situational influences People least likely to conform have: Willingness to conform also depends on: |

Neural Processes fMRIs provide evidence that: |

246