8.1 Elaboration Likelihood Model: Central and Peripheral Routes to Persuasion

In earlier chapters we made the point that people often are unwilling or unable to think deeply about every decision they make and every piece of information they encounter. As a result, they sometimes engage in controlled, deliberate thinking. At other times, they think in a more automatic and superficial manner. (For a refresher on this fundamental principle, see the section “Dual Process Theories” in chapter 3.) The elaboration likelihood model (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986), or ELM, is a theory of persuasion that builds on this distinction. This theory proposes that persuasive messages can influence attitudes in two different ways, or routes. Which route a person takes depends on his or her motivation and ability to elaborate on—

Elaboration likelihood model

A theory of persuasion that proposes that persuasive messages can influence attitudes by two different routes, central or peripheral.

274

People follow the central route to persuasion when they think carefully about the information that is pertinent, or central, to the true merits of the person, object, or position being advocated in the message. This information is referred to as the argument. For example, people who follow the central route while listening to a political candidate’s speech will attend closely to the candidate’s arguments concerning why he or she will make a good leader and they will consider whether those arguments are factual and cogent. Thus, when people follow the central route, their attitudes are influenced primarily by the strength of the argument. Strong arguments will change attitudes; weak arguments will not.

Central route to persuasion

A style of processing a persuasive message by a person who has both the ability and the motivation to think carefully about the message’s argument. Attitude change depends on the strength of the argument.

Argument

The true merits of the person, object, or position being advocated in the message.

In contrast, people follow the peripheral route to persuasion when they are not willing or able to put effort into thinking carefully about the argument. In these cases, people’s attitudes are influenced primarily by peripheral cues, which are aspects of the communication that are irrelevant (that is, peripheral) to the true merits of the person, object, or position advocated in the message. For example, people following the peripheral route while listening to a candidate’s speech are not thinking carefully about the candidate’s arguments. Instead, they might focus on the candidate’s physical attractiveness or the smiling faces of the school children standing behind the candidate. People taking the peripheral route also tend to base their attitudes on heuristics—mental short cuts such as, “If a person speaks for a long time, then they must have a valid point” (see chapter 3) (Chaiken, 1987).

Peripheral route to persuasion

A style of processing a persuasive message by a person who is not willing or able to put effort into thinking carefully about the message’s argument. Attitude change depends on the presence of peripheral cues.

Peripheral cues

Aspects of the communication that are irrelevant (that is, peripheral) to the true merits of the person, object, or position advocated in the message (e.g., a speaker’s physical attractiveness when attractiveness is irrelevant to the position).

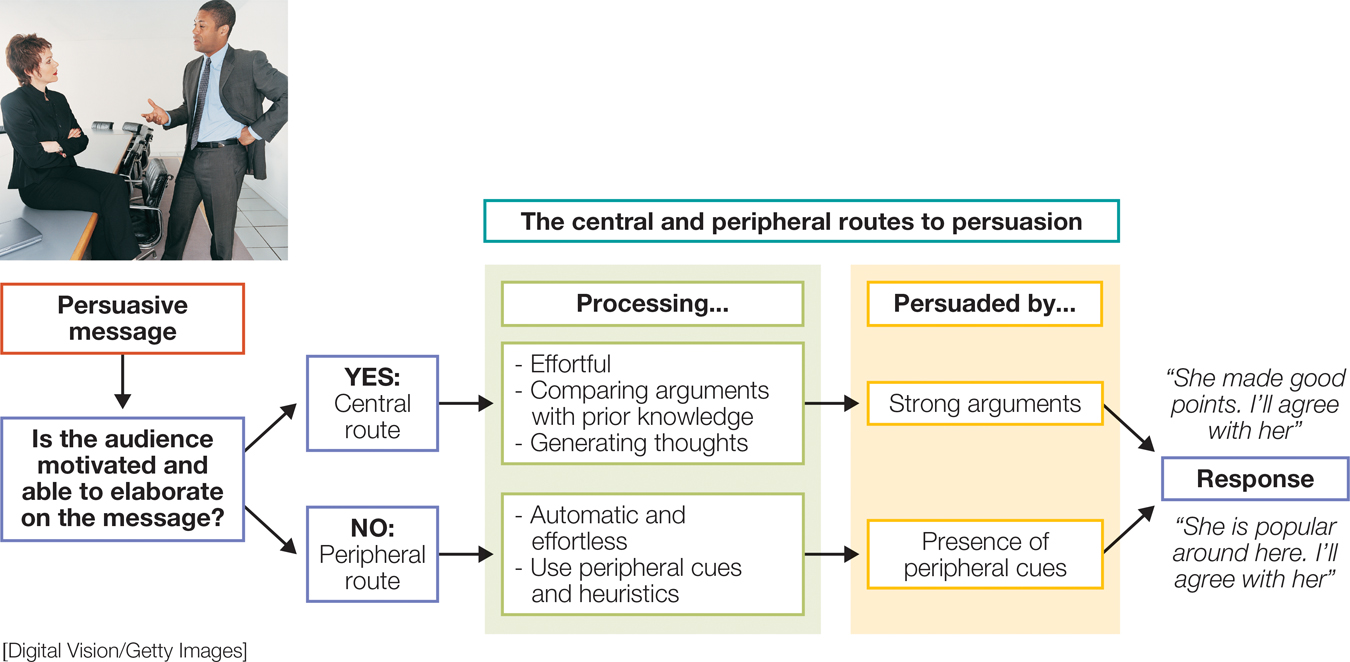

FIGURE 8.2

The Elaboration Likelihood Model

The central and peripheral routes represent two distinct pathways of persuasion.

[Digital Vision/Getty Images]

Note that whether people follow the central route or the peripheral route does not necessarily lead them to have more positive or more negative attitudes. In our example, a person who is diligently considering the candidate’s arguments, and another person who is wowed by the surrounding pageantry, both may report the same increase or decrease in liking for the candidate. Rather, which route people follow determines which aspects of the persuasive message have the strongest influence on their attitudes. (FIGURE 8.2 presents a summary of the two routes to persuasion.)

Why do people take one or the other route? According to the ELM, the key factors are the individual’s motivation and ability to think deeply about the message. When motivation and ability to process the message are high, the person will usually take the central route. But when the person lacks either the motivation or the ability to process the message, he or she will be more likely to take the peripheral route. Next we’ll look at research testing these hypotheses.

Motivation to Think

It makes sense that the more relevant a message is to a person’s goals and interests, the more effort he or she will devote to thinking deeply about the message. Imagine, for example, that Jill is watching a commercial for Brand X computers. Because she relies on her laptop a lot and is in the market for a new one, this message is pertinent to Jill’s goals. We would therefore expect Jill to concentrate on the commercial’s argument and think critically about its claims (“They say this model has a big hard drive, but do I really need that?”). Bill, on the other hand, is not really into computers, and so he will be less motivated to consider the pros and cons of the advertised brand. Instead, Bill will likely take the peripheral route and base his attitudes toward Brand X on the presence of peripheral cues such as a catchy jingle or a sexy spokesperson.

275

An influential study by Rich Petty and colleagues (1983) demonstrates that a message’s relevance to people’s goals determines which persuasion route they take. Participants were asked to take part in a study on consumer attitudes. They were told that, as a reward for participating, they would be able to choose a product from among a few different brands at the end of the study. Some participants were told that they could choose from among different brands of razor blades; others were told that they could choose from among brands of toothpaste. Later, when all participants were asked to flip through some ads, they came upon an ad for Edge razor blades. You can imagine that this ad was relevant for participants expecting to choose a brand of razor blades but not for those expecting to choose a toothpaste brand.

The researchers introduced two other variables. First, half the participants read strong arguments for the Edge razor’s quality, such as “Special chemically formulated coating eliminates nicks and cuts and prevents rusting.” The other half read weak arguments, such as “Designed with the bathroom in mind.” Second, one version of the ad featured an attractive celebrity endorsing the Edge razor, whereas the other version featured anonymous, average-

What influenced participants’ attitudes toward the Edge razor? When participants expected to choose a razor later on—

276

Ability to Think

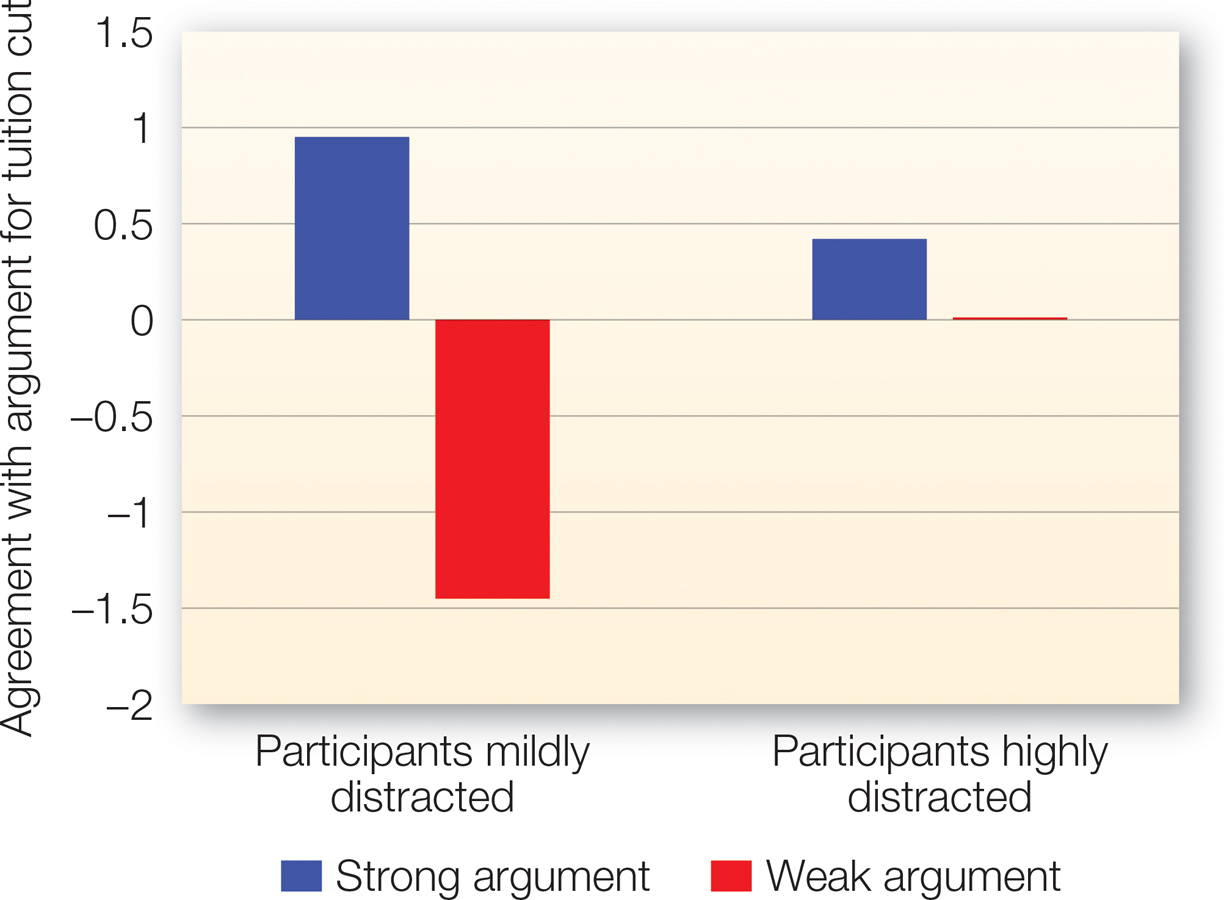

FIGURE 8.3

The Effects of Distraction on Persuasion

In this study, people who were only mildly distracted were persuaded through the central route; they agreed more with a planned tuition cut if the arguments they heard were strong and disagreed with it if the arguments were weak. But being highly distracted switched them to the peripheral route, and their agreement with the proposal was unaffected by the strength of the argument.

[Data source: Petty et al. (1976)]

Let’s revisit Jill, who is processing a commercial advertising Brand X computers. We mentioned that, other things being equal, Jill will be motivated to think about the commercial’s central arguments because they are relevant to her goal of purchasing a new computer. But of course things are not always equal: Perhaps Jill is watching the commercial while she is hungry, hung over, or bombarded with the sounds of a nearby construction site. According to the ELM, even if people are motivated to think carefully about a message, they may be unable to do so because of distractions and other demands on their attention. Under these conditions, people will tend to take the peripheral route to persuasion.

This is demonstrated in another study by Petty and colleagues (1976). Participants listened to a recorded message arguing that the tuition at their university should be cut in half. Participants heard either strong arguments in favor of the tuition cut (such as “The currently high tuition prevents high school students from going to college”) or weak arguments (“Cutting tuition would lead to increased class size”). While they listened to the message, participants repeatedly were asked to record the location of an “X” which appeared at various spots on a screen in front of them. For some participants, the Xs flashed every 15 seconds. You can imagine this would be mildly distracting. But other participants had to identify the X every 5 seconds—

Why It Matters

Why does it matter which route people take if either one can lead them to change their attitudes? Compared with attitudes formed through the peripheral route, attitudes formed through the central route are stronger—

Consistent with this reasoning, studies show that attitudes formed through central-

277

To sum up, following the central or the peripheral route to persuasion orients people toward different aspects of a persuasive message. We’ve looked at some of those aspects, such as the attractiveness of a celebrity. Next we consider those aspects in more detail, grouping them into three categories: Who says What to Whom. First, we’ll see how attitudes are influenced by characteristics of the individual or group communicating the message (the “Who,” or source). Then we’ll look at the characteristics of the message itself (the “What”). Finally, we’ll consider characteristics of the person or group receiving the message (“Whom,” or the audience).

Source

The person or group communicating the message.

Audience

The person or group receiving the message.

|

Elaboration Likelihood Model |

|

The elaboration likelihood model proposes that a persuasive message can influence attitudes by two different routes, depending on a person’s motivation and ability to think carefully about the message. |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Motivation When people are motivated to think carefully about the message, they take the central route, basing their attitudes on argument strength. If people are less motivated, they take the peripheral route, basing their attitudes on peripheral cues. |

Ability When people have the mental resources to think carefully about the message, they take the central route. If people are cognitively busy, they take the peripheral route. |

Persistence Attitude change produced by central- |