8.4 Characteristics of the Audience

In addition to the source of a persuasive message and the nature of the message itself, a message’s impact on an audience also depends on the characteristics of the audience members. Whether a given audience member responds favorably or unfavorably to a message is determined by his or her individual age, sex, personality, socioeconomic status, education level, and habitual way of living, as well as the events and experiences of his or her life. For example, we described earlier that whether a person processes a persuasive message through the central route or the peripheral route depends in part on his or her motivation to attend to the message. So we would expect that individual differences in interests, values, and prior knowledge will determine who finds certain messages worthy of attention or not. Let’s consider how audiences differ according to the following characteristics.

Persuasibility

People differ in their overall persuasibility, their susceptibility to persuasion. People high in persuasibility are more likely to yield to persuasive messages, whereas low-

Age: Between the ages of 18 to 25, people are usually in the process of forming their attitudes, and so they are more likely to be influenced by persuasive messages. As they move into their late 20s and beyond, their attitudes tend to solidify and become more resistant to change (Koenig et al., 2008; Krosnick & Alwin, 1989).

Self-

293

Education and intelligence: Audience members who are more educated and intelligent are less persuadable than those with normal to low intelligence (McGuire, 1968). We can interpret this finding in a similar way as the self-

Initial Attitudes

Another important audience characteristic is the attitude that audience members already have toward the position advocated in the message. Imagine that you are trying to persuade your parents that you should be allowed to study in Spain for a semester through a foreign exchange program. Would you be more effective if you presented only those arguments favoring a semester abroad and ignored any arguments opposed to your position—

Whether a one-

Why is this the case? If audience members are initially leaning toward disagreement, they are probably aware of at least a few arguments opposing the position advocated in the message. For example, if your parents are already inclined to oppose the semester abroad, they probably have some reasons (e.g., it is too dangerous). Thus, if the message ignores the audience’s opposing arguments, the audience will likely conclude that the communicator is biased, uninformed, or manipulative, and they will call into question the validity of anything he or she says.

If, however, the audience is already leaning toward agreement with the message, they are less likely to be aware of opposing arguments. Therefore, simply mentioning those opposing arguments may confuse audience members or lead them to conclude that the issue is more controversial than they initially thought. (“Hmm, I was all for the semester abroad, but now that you mention it, the trip would be awfully expensive.”) In this case you would have been more persuasive if you had focused only on those arguments favoring your position.

Need for Cognition and Self-monitoring

Think back to the study we discussed in this chapter looking at attitudes toward Edge razor blades (Petty et al., 1983). That study showed that a person’s motivation to think about a message can vary from situation to situation depending on whether that message pertains to his or her current goals and interests (e.g., anticipating a choice between razors or toothpastes). But you may have noticed that, across different situations, some people are generally more interested in thinking deeply about issues, whereas others are not. According to Cacioppo and Petty (1982), individuals high in need for cognition tend to think about things critically and analytically and enjoy solving problems. They tend to agree strongly with statements such as “I really enjoy a task that involves coming up with new solutions to problems.” Individuals low in need for cognition are less interested in effortful cognitive activity and agree with statements such as “I think only as hard as I have to.” With your knowledge of the elaboration likelihood model (ELM), do you suspect that individuals with high need for cognition would tend to take the central route or the peripheral route to persuasion?

Need for cognition

Differences between people in their need to think about things critically and analytically.

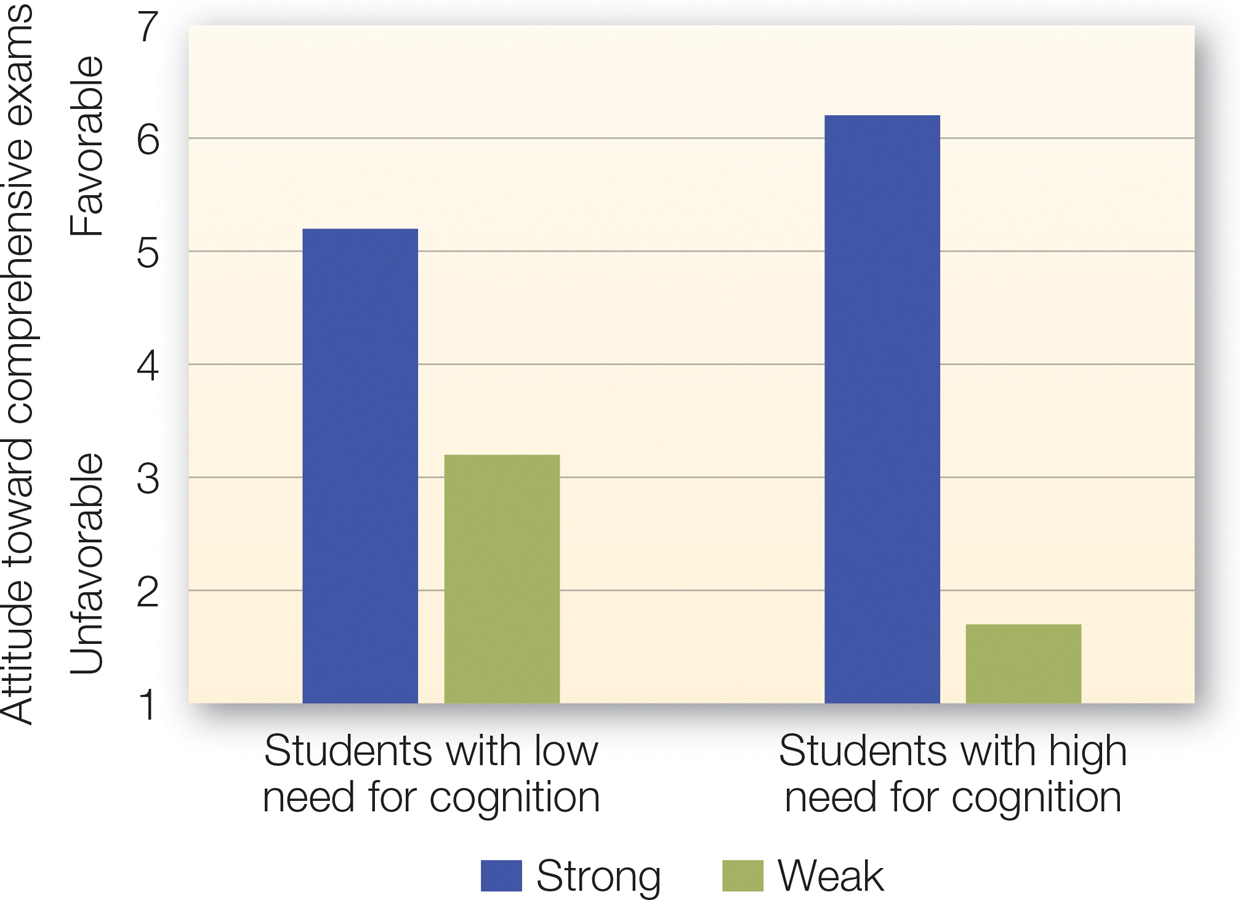

FIGURE 8.10

Need for Cognition

People who have a high need for cognition like to think deeply and are more persuadable through the central route. In this study, students high in need for cognition were more positive toward a proposed comprehensive exam if the arguments for it were strong than if the arguments were weak. Those low in need for cognition were less sensitive to argument strength.

[Data source: Cacioppo et al. (1983)]

294

If you said central, you’re right. This was shown in a study by John T. Cacioppo and his colleagues (1983). The researchers measured college students’ need for cognition, then asked them to read an editorial, allegedly written by a journalism student, arguing that all seniors be required to pass a rigorous, comprehensive exam to graduate. Thus, in this experiment, the message is relevant to all the participants. But for half the participants, the editorial contained fairly strong arguments in favor of the exam (“The quality of undergraduate teaching has improved at schools with the exams”), whereas the other participants read fairly unconvincing arguments for the exam (“The risk of failing the exam is a challenge more students would welcome”). Overall, as you might expect, participants were more favorable toward the exam requirement when it was supported by strong rather than weak arguments. But participants with high need for cognition were especially likely to approve of the proposal when it was supported by strong arguments and to disapprove of the proposal when it was supported by weak arguments (see FIGURE 8.10). So even though the message was equally relevant to all participants, some of them were inherently motivated to pay close attention to the arguments, whereas others were content merely to skim the message.

SOCIAL PSYCH at the MOVIES

Argo: The Uses of Persuasion

Argo: The Uses of Persuasion

In 1979, Iranian militants stormed the U.S. embassy in Tehran, taking 52 Americans hostage in retaliation for what they saw as American meddling in Iran’s government. Six U.S. diplomats managed to slip away and found refuge in the home of the Canadian ambassador. They feared that it was only a matter of time before they were discovered by Iranian revolutionaries and likely killed, so they could not just arrive at Tehran’s airport and reveal their American identities.

Back in the United States, the CIA operative Tony Mendez came up with a plan to get the diplomats safely out of the country: convince the Iranians that the diplomats were Canadian filmmakers who were in Iran scouting exotic locations for a sci-

Mendez first has to persuade the higher-

Eventually Mendez gets the green light and works with the Hollywood makeup artist John Chambers (John Goodman) and the producer Lester Siegel (Alan Arkin) to set up a phony movie-

The next group that needs to be persuaded are the people whose lives are on the line. Posing as Argo’s producer, Mendez meets the diplomats who are in hiding and provides them with Canadian passports and fake identities. But he also gives them a crash course in the film industry and Canadian citizenship. After all, if they have any chance of making it past the authorities and getting on the plane, they need to play their roles convincingly. But they too are skeptical of Mendez’s scheme and reluctant to go along with it. At first Mendez tries to persuade them by presenting himself as a trustworthy source, a powerful peripheral cue when audiences take the peripheral route. But the diplomats aren’t processing information peripherally. The outcome of what happens is incredibly relevant to them, and that elicits central route processing. Shifting gears, Mendez takes the time to deliver a strong argument for why they should trust him. He reveals his true identity and describes his training and his record of successful rescue missions. He also reminds them that he is risking his own life, too. He knows that the source of a message can gain credibility by being perceived as having nothing to gain by deception or manipulation. His willingness to risk his own life is evidence that he firmly believes that the plan can work, and the diplomats begin getting into character.

In the movie’s suspenseful climax, we watch the “film crew” slowly making their way through security checkpoints in Tehran’s airport. Gun-

295

296

Just as some people are motivated to think in greater depth, other people are motivated to make a good impression and present a desired social image. Recall our discussion of self-

In one study, not only were high self-

Regulatory Focus

Earlier we noted that in certain situations, people are influenced by thinking about what they might gain, whereas in other situations they are influenced by thinking about what they could lose (Rothman, 2000). It turns out there is an additional piece to this puzzle that can further enhance our understanding of which people will be most persuaded by which type of message. Some people generally are oriented more toward the promotion of positive outcomes. Their actions are strongly driven by the growth motivation that we discussed in chapter 2. Consider Frank, who works out and watches what he eats so that he can look more like Ryan Reynolds. Other people are oriented more toward the prevention of negative outcomes. They are motivated to maintain security (see chapter 2). Consider Stephen, who works out and watches what he eats so he can avoid looking like Minnesota Fats. Note that Frank and Stephen engage in the same types of behavior, but they regulate their behavior according to two very different endpoints. We would say that Frank is high in promotion focus, whereas Stephen is high in prevention focus.

Promotion focus

People’s general tendency to think and act in ways oriented toward the approach of positive outcomes.

Prevention focus

People’s general tendency to think and act in ways oriented toward the avoidance of negative outcomes.

Why does this matter for persuasion? Because individual differences in promotion focus and prevention focus can determine which types of persuasive messages are more influential. In one study (Cesario et al., 2004) participants read an argument in favor of a new afterschool program. For some participants, the program was billed as catering to a positive end state (facilitating children’s progress and graduation). For other participants, it was billed as preventing a negative end state (ensuring that fewer children failed). For participants who were promotion focused, the promotion-

The regulatory fit between the characteristics of the audience and those of the message has important implications not only for changing attitudes but also for changing behavior. Let us return to the examples of Frank and Stephen. Because Frank is promotion focused, it might be easier to persuade him to start a weight-

297

|

Characteristics of the Audience |

|

A message’s influence on attitudes and behavior depends on who receives it. |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Three determinants of persuasibility Age. Self- Education and intelligence. |

Initial attitudes One- Two- |

How people think and self- People with high need for cognition prefer the central route. Those motivated to make a good impression are more susceptible to peripheral route cues. |

Regulatory style For audiences high in promotion focus, influential messages highlight positive outcomes. Prevention- |