10.2 Six Major Categories of Mental Disorders

As you read this section, beware of the “medical school syndrome”—the tendency to think that you have a disease (disorder in our case) when you read about its symptoms. Symptoms are behaviors or mental processes that indicate the presence of a disorder. The symptoms of many disorders often involve behavior and thinking that we all experience, which may lead us to think we have the disorders. To prevent such misdiagnoses, remember the criteria that we discussed for distinguishing abnormal behavior and thinking. For example, we all get anxious or depressed (symptoms of several different disorders) at different times in our lives for understandable reasons, such as an upcoming presentation or a death in the family. These feelings of anxiety and depression only become symptoms of a disorder when they prevent us from functioning normally. We are suffering from a disorder only if our reactions to life’s challenges become atypical, maladaptive, disturbing to ourselves or others, and irrational.

biopsychosocial approach Explaining abnormality as the result of the interaction among biological, psychological (behavioral and cognitive), and sociocultural factors.

What causes such abnormal behavior and thinking? Most causal explanations for mental disorders are tied to the four major research approaches—

| Major Category | Specific Disorder(s) Within Category |

|---|---|

| Anxiety disorders | Specific phobia, social anxiety disorder (social phobia), agoraphobia, panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder |

| Obsessive- |

Obsessive- |

| Depressive disorders | Major depressive disorder |

| Bipolar and related disorders | Bipolar disorder |

| Schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders | Schizophrenia |

| Personality disorders | Avoidant personality disorder, schizoid personality disorder, antisocial personality disorder |

Anxiety Disorders

anxiety disorders Disorders that share features of excessive fear and anxiety and related behavioral disturbances, such as avoidance behaviors.

We all have experienced anxiety. Don’t you get anxious at exam times, especially at final exam time? Most students do. How do you feel when you are about to give an oral presentation? Anxiety usually presents itself again. These are normal reactions, not signs of a disorder. Anxiety disorders are disorders that share features of excessive fear and anxiety and related behavioral disturbances, such as avoidance behaviors (APA, 2013). In anxiety disorders, the anxiety and fear often occur inexplicably and are so intense that they prevent the person from functioning normally in daily life. The specific anxiety disorders differ from one another in the types of objects and situations that induce the excessive fear and anxiety. Because anxiety disorders are some of the most common disorders in the United States (Hollander & Simeon, 2011; cf. Horwitz & Wakefield, 2012), we’ll discuss several different anxiety disorders—

specific phobia An anxiety disorder indicated by a marked and persistent fear of specific objects or situations that is excessive and unreasonable.

Specific phobia. According to the DSM-

| Phobia | Specific Fear |

|---|---|

| Acrophobia | Fear of heights |

| Aerophobia | Fear of flying |

| Agyrophobia | Fear of crossing streets |

| Arachnophobia | Fear of spiders |

| Claustrophobia | Fear of closed spaces |

| Cynophobia | Fear of dogs |

| Gamophobia | Fear of marriage |

| Gephyrophobia | Fear of crossing bridges |

| Hydrophobia | Fear of water |

| Ophidiophobia | Fear of snakes |

| Ornithophobia | Fear of birds |

| Pyrophobia | Fear of fire |

| Thanatophobia | Fear of death |

| Xenophobia | Fear of strangers |

| Zoophobia | Fear of animals |

To emphasize this difference, consider this brief description of a case of a woman with a specific phobia of birds. She became housebound because of her fear of encountering a bird. Any noises that she heard within the house she thought were birds that had somehow gotten in. Even without encountering an actual bird, the dreaded anticipation of doing so completely controlled her behavior. When she did leave her house, she would carefully back out of her driveway so that she did not hit a bird; she feared that the birds would retaliate if she did. She realized that such cognitive activity was beyond the capabilities of birds, but she could not control her fear. Her behavior and thinking were clearly abnormal.

What causes a specific phobia? One biopsychosocial answer involves both behavioral and biological factors. We learn phobias through classical conditioning and are biologically predisposed to learn some fears more easily than others. We are conditioned to fear a specific object or situation. Remember Watson and Rayner’s study described in Chapter 4 in which they classically conditioned Little Albert to fear white rats? Behavioral psychologists believe that the fears in specific phobias are learned the same way, but through stressful experiences in the real world, especially during early childhood. For example, a fear of birds might be due to the stressful experience of seeing Alfred Hitchcock’s movie The Birds (in which birds savagely attack humans) at a young age. You should also remember from Chapter 4 that biological preparedness constrains learning. Certain associations (such as taste and sickness) are easy to learn, while others (such as taste and electric shock) are very difficult. This biological preparedness shows up with specific phobias in that fears that seem to have more evolutionary survival value, such as fear of heights, are more frequent than ones that do not, such as fear of marriage (McNally, 1987). It is also more difficult to extinguish fears that have more evolutionary survival value (Davey, 1995).

social anxiety disorder An anxiety disorder indicated by a marked and persistent fear of one or more social performance situations in which embarrassment may occur and in which there is exposure to unfamiliar people or scrutiny by others.

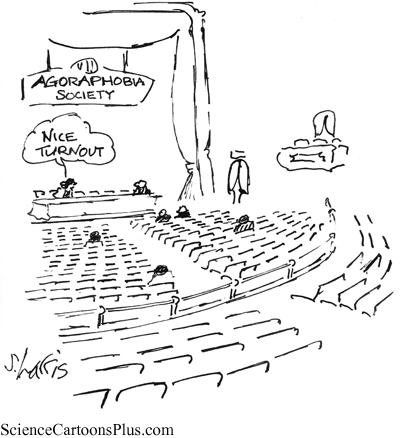

Social anxiety disorder (social phobia) and agoraphobia. Most phobias are classified as specific phobias, but the DSM-

agoraphobia An anxiety disorder indicated by a marked and persistent fear of being in places or situations from which escape may be difficult or embarrassing.

Social anxiety disorder is different from agoraphobia, the fear of being in places or situations from which escape may be difficult or embarrassing. The name of this disorder literally means fear of the marketplace; in Greek, “agora” means marketplace, and “phobia” means fear. In addition to the marketplace, situations commonly feared in agoraphobia include being in a crowd, standing in a line, and traveling in a crowded bus or train or in a car in heavy traffic. To avoid these situations, people with agoraphobia usually won’t leave the security of their home. Surveys reveal that about 7% of people in the United States suffer from social anxiety disorder in any given year but only about 2% from agoraphobia (Kessler, Ruscio, Shear, & Wittchen, 2010; NIMH, 2011). Just as for specific phobias, a behavioral-

panic disorder An anxiety disorder in which a person experiences recurrent panic attacks.

Panic disorder. Panic disorder is a condition in which a person experiences recurrent panic attacks—

Biological explanations of panic disorder involve abnormal neurotransmitter activity, especially that of norepinephrine, and improper functioning of a panic brain circuit, which includes the amygdala, hypothalamus, and some other areas in the brain. Cognitive explanations involve panic-

generalized anxiety disorder An anxiety disorder in which a person has excessive, global anxiety and worries that he cannot control, occurring more days than not for at least a period of 6 months.

Generalized anxiety disorder. Panic attacks occur suddenly in panic disorder. In generalized anxiety disorder, the anxiety is chronic and lasts for months. Generalized anxiety disorder is a disorder in which a person has excessive, global anxiety that he cannot control, occurring more days than not for at least 6 months (APA, 2013). The person just cannot stop worrying, and the anxiety is general—

Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders

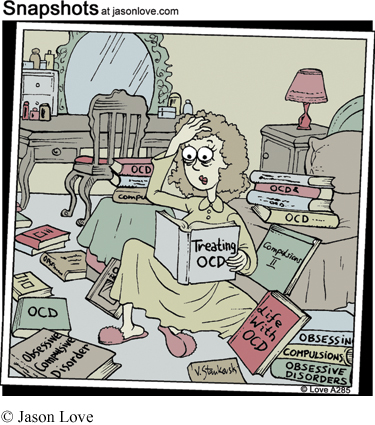

Obsessive-

obsessive-

obsession A persistent intrusive thought, idea, impulse, or image that causes anxiety.

compulsion A repetitive and rigid behavior that a person feels compelled to perform in order to reduce anxiety.

Obsessive-

It is important to realize that many people experience minor obsessions (e.g., a pervasive worry about upcoming exams) or compulsions (e.g., arranging their desks in a certain way), but they do not have this disorder. People with obsessive-

It is not known for sure what causes obsessive-

Obsessive-

Hoarding disorder reflects a persistent difficulty in discarding or parting with possessions due to a perceived need to save the items and the distress associated with discarding them. This need to save items results in an extraordinary accumulation of clutter. Parts of the home may become inaccessible because of the stacks of clutter occupying those areas. Sofas, beds, and other pieces of furniture may be unusable, because they are filled with stacks of hoarded items. Such clutter may not only impair personal and social functioning but also result in fire hazards and unhealthy sanitary conditions. Prevalence rates for hoarding disorder are not available, but it appears to be more prevalent in older adults than younger adults (APA, 2013). About 75% of individuals with hoarding disorder also have an anxiety or depressive disorder, with the most common being major depressive disorder (APA, 2013). Having another disorder is important, because it may often be the main reason for consultation. Individuals with hoarding disorder seldom seek consultation for hoarding symptoms.

People with excoriation (skin-

People with trichotillomania (hair-

Depressive Disorders

depressive disorders Disorders that involve the presence of sad, empty, or irritable mood, accompanied by somatic and cognitive changes that significantly affect the individual’s capacity to function.

Depressive disorders involve the presence of sad, empty, or irritable mood, accompanied by somatic and cognitive changes that significantly affect the individual’s capacity to function. Major depressive disorder (sometimes called unipolar depression) represents the classic condition in this category, so it is the depressive disorder that we will discuss.

major depressive disorder A depressive disorder in which the person has experienced one or more major depressive episodes.

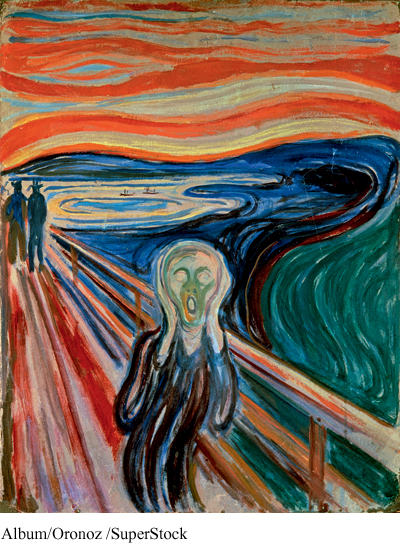

major depressive episode An episode characterized by symptoms such as feelings of intense hopelessness, low self-

Major depressive disorder. When people say that they are depressed, they usually are referring to their feelings of sadness and downward mood following a stressful life event (such as the breakup of a relationship or the loss of a job). Such mood changes are understandable and over time usually right themselves. A major depressive disorder, however, is debilitating, has an impact on every part of a person’s life, and usually doesn’t right itself. To be classified as having a major depressive disorder, a person must have experienced one or more major depressive episodes. A major depressive episode is characterized by symptoms such as feelings of intense hopelessness, low self-

The 12-

There is also a recent argument that the high prevalence rate for depression is spurious, in that it is due to overdiagnosis caused by insufficient diagnostic criteria (Horwitz & Wakefield, 2007). True mental disorders are usually rare, with very low prevalence rates, but depression has a high prevalence rate. According to Andrews and Thomson (2009, 2010), the fact that depression has a high prevalence rate poses an evolutionary paradox, because the pressures of evolution should have led our brains to resist such a high rate of malfunction. Andrews and Thomson propose that much of what is diagnosed as depression should not be thought of as a true mental disorder (a brain malfunction) but rather as an evolutionary mental adaptation (stress response mechanism) that focuses the mind to better solve the complex life problems that brought about the troubled state. This is an intriguing hypothesis with implications not only for the diagnostic criteria for this disorder but also for the therapeutic approaches to treat it.

Traditional explanations of major depressive disorder propose both biological and psychological factors as causes. A leading biological explanation involves neurotransmitter imbalances, primarily inadequate serotonin and norepinephrine activity. Antidepressant drugs (to be discussed later in the chapter) are the most common treatment for such imbalances. There is also evidence of a genetic predisposition for this disorder (Levinson & Nichols, 2014; Tsuang & Faraone, 1990). The likelihood of one identical twin getting a disorder given that the other identical twin has the disorder is the concordance rate for identical twins for the disorder. McGuffin, Katz, Watkins, and Rutherford (1996) looked at almost 200 pairs of twins and found that the concordance rate for identical twins is 46%, which is significantly greater than the 20% found for fraternal twins. Adoption studies have also implicated a genetic predisposition, at least for major depressive disorder (Kamali & McInnis, 2011). The biological parents of adoptees who had been diagnosed with this disorder were found to have a higher incidence of severe depression than the biological parents of adoptees who had not been diagnosed with this disorder.

Brain researchers have recently proposed a brain circuit responsible for unipolar depression (Treadway & Pizzagalli, 2014). Brain-

There are a panoply of other biological theories about depression and treatments for it. An interesting one involves a toxin, botulinum poison, which we discussed in Chapter 2. Remember, an extremely mild form of this poison is used in Botox treatments for facial wrinkling. Depending upon the injection site, particular facial expression muscles are paralyzed temporarily. According to this theory, information flows both ways in the circuit connecting the brain with these facial muscles. The brain monitors the emotional valence (expression) of the face and responds by generating the appropriate feeling, and conversely, the brain can direct the facial muscles to generate specific expressions depending upon what the brain judges our emotional state to be. This theory is congruent with the theories of emotion that we discussed in Chapter 2. Remember, for example, that the Schachter and Singer two-

It is clear, however, that major depressive disorder is not totally biological in origin. Thus, nonbiological factors are also seen as causes in major depressive disorder. For example, cognitive factors have been found to be important. The person’s perceptual and cognitive processes are assumed to be faulty, causing the depression. We discussed an example of such faulty cognitive processing in Chapter 8. Remember the pessimistic explanatory style in which a person explains negative events in terms of internal (her own fault), stable (here to stay), and global (applies to all aspects of her life) causes. Such a style, paired with a series of negative events in a person’s life, will lead to learned helplessness and depression. Thus, the cause of the person’s depression is her own thinking, in this case how she makes attributions. Cognitive therapies, which we will discuss later in this chapter, attempt to replace such maladaptive thinking with more adaptive thinking that will not lead to depression. These therapies have been shown to be just as effective as drug therapy in treating depression (DeRubeis et al., 2005).

Bipolar and Related Disorders

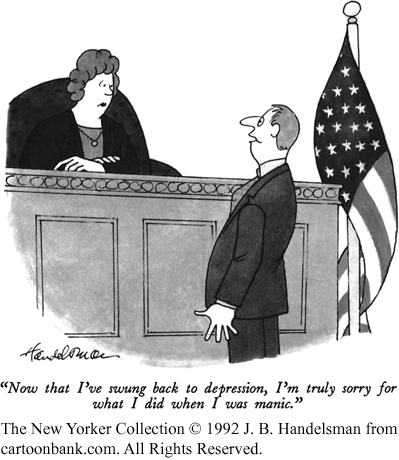

manic episode An episode characterized by abnormally elevated mood in which the person experiences symptoms such as inflated self-

Major depressive disorder is often referred to as unipolar depression or a unipolar disorder to contrast it with bipolar disorder, another disorder in which the person’s mood takes dramatic mood swings between depression and mania. Such disorders used to be called “manic–

Consider the following behavior of a person experiencing a manic episode. A postal worker stayed up all night and then went off normally to work in the morning. He returned later that morning, however, having quit his job, withdrawn all of the family savings, and spent it on fish and aquariums. He told his wife that, the night before, he had discovered a way to keep fish alive forever. He then ran off to canvass the neighborhood for possible sales. This person showed poor judgment and a decreased need for sleep, and his behavior disrupted his normal functioning (he quit his job). In the beginning, milder stages of a manic episode, some people become not only more energetic but also more creative, until the episode accelerates and their behavior deteriorates.

bipolar disorder A disorder in which recurrent cycles of depressive and manic episodes occur.

There is no diagnosis for mania alone. It is part of a bipolar disorder in which recurrent cycles of depressive and manic episodes occur. A bipolar disorder is an emotional roller coaster, with the person’s mood swinging from manic highs to depressive lows. There are two types of bipolar disorder. In Bipolar I disorder, the person has both major manic and depressive episodes. In Bipolar II disorder, the person has full-

Because the concordance rate for identical twins for bipolar disorder is so strong, 70% (Tsuang & Faraone, 1990), biological causal explanations are the most common. In fact, researchers are presently working on identifying the specific genes that make a person vulnerable to bipolar disorder. As with major depressive disorder, the biological predisposition shows up as neurotransmitter imbalances. In this case, the imbalances swing between inadequate activity (depression) and too much activity (mania). The most common treatment is drug therapy, and the specific drugs used will be discussed later in the chapter.

Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorders

We will only be discussing schizophrenia from this category. It is the disorder that people are usually thinking of when they use words such as “insane” and “deranged.” More people are institutionalized with schizophrenia than with any other disorder, and schizophrenia is much more difficult to successfully treat than other mental disorders. Thankfully, only about 1% of the population suffers from this disorder (Gottesman, 1991). The onset of schizophrenia is usually in late adolescence or early adulthood. Men and women are equally likely to develop schizophrenia, but it tends to strike men earlier and more severely (Lindenmayer & Khan, 2012). Schizophrenia is more common in the lower socioeconomic classes than in the higher ones, and also for those who are single, separated, or divorced (Sareen et al., 2011). In addition, people with schizophrenia have an increased risk of suicide, with an estimated 25% attempting suicide (Kasckow, Felmet, & Zisook, 2011).

psychotic disorder A disorder characterized by a loss of contact with reality.

Schizophrenia is referred to as a psychotic disorder, because it is characterized by a loss of contact with reality. The word “schizophrenia” is Greek in origin and literally means “split mind.” This is not a bad description; in a person with schizophrenia, mental functions become split from one another and the person becomes detached from reality. The person has trouble distinguishing reality from his own distorted view of the world. This splitting of mental functions, however, has led to the confusion of schizophrenia with “split personality” or multiple personality disorder (now called dissociative identity disorder in the DSM-

The symptoms of schizophrenia. The symptoms of schizophrenia vary greatly, but they are typically divided into three categories—

hallucination A false sensory perception.

delusion A false belief.

Positive symptoms are the more active symptoms that reflect an excess or distortion of normal thinking or behavior, including hallucinations (false sensory perceptions) and delusions (false beliefs). Hallucinations are usually auditory, hearing voices that aren’t really there. Remember, the fake patients in Rosenhan’s study said that they heard voices and were admitted and diagnosed as having a schizophrenic disorder. Delusions fall into several categories, such as delusions of persecution (for example, believing that one is the victim of conspiracies) or delusions of grandeur (for example, believing that one is a person of great importance, such as Jesus Christ or Napoleon). Hallucinations and delusions are referred to as positive symptoms because they refer to things that have been added.

Negative symptoms are deficits or losses in emotion, speech, energy level, social activity, and even basic drives such as hunger and thirst. For example, many people with schizophrenia suffer a flat affect in which there is a marked lack of emotional expressiveness. Their faces show no expression, and they speak in a monotone. Similarly, there may be a serious reduction in their quantity and quality of speech. People suffering from schizophrenia may also lose their energy and become extremely apathetic—

Disorganized symptoms include nonsensical speech and behavior and inappropriate emotion. Disorganized speech sounds like a “word salad,” with unconnected words incoherently spoken together and a shifting from one topic to another without any apparent connections. One thought does not follow the other. Those who show inappropriate emotion may smile when given terrible news. Their emotional reactions seem unsuited to the situation.

Behavior may also be catatonic—

schizophrenia A psychotic disorder in which at least two of the following symptoms are present most of the time during a 1-

According to the DSM-

Clinicians have used the various types of symptoms of schizophrenia and their course of development to make distinctions between types of schizophrenia. One such distinction, between chronic and acute schizophrenia, deals with how quickly the symptoms developed. In chronic schizophrenia, there is a long period of development, over years, and the decline in the person’s behavior and thinking occurs gradually. In acute schizophrenia, there is a sudden onset of symptoms that usually can be attributed to a crisis in the person’s life, and the person functioned normally before the crisis with no clinical signs of the disorder. Acute schizophrenia is more of a reactive disorder, and recovery is much more likely.

Another distinction is between Type I and II schizophrenia (Crow, 1985). Type I is characterized by positive symptoms, and Type II by negative symptoms. Type I is similar to acute schizophrenia: The person has usually functioned relatively normally before the disorder strikes, and there is a higher likelihood of recovery. People with Type I schizophrenia respond better to drug therapy than do those with Type II. This difference may be because the positive symptoms of Type I result from neurotransmitter imbalances, which are affected by drugs, whereas the more permanent structural abnormalities in the brain that produce the negative symptoms of Type II are not as affected by drugs.

The causes of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia seems to have many different causes, and we do not have a very good understanding of any of them. Hypothesized causes inevitably involve a genetic or biological predisposition factor. There definitely appears to be a genetic predisposition to some schizophrenia; it seems to run in families, with the concordance rate for identical twins similar to that for a major depression, about 50% (DeLisi, 1997; Gottesman, 1991). This is significantly greater than the 17% concordance rate for fraternal twins. In addition, recently the biggest-

Nongenetic biological factors also likely play a role in the development of schizophrenia. One hypothesis involves prenatal factors, such as viral infections (Brown, 2006; Washington, 2015). Research has found that people are at increased risk for schizophrenia if there was a flu epidemic during the middle of their fetal development (Takei, Van Os, & Murray, 1995; Wright, Takei, Rifkin, & Murray, 1995). There is even a birth-

Prenatal or early postnatal exposure to several other viruses (e.g., herpes simplex virus) has also been associated with the later development of schizophrenia (Yolken & Torrey, 1995). Even exposure to house cats has been proposed as a risk factor for the development of schizophrenia (Torrey, Rawlings, & Yolken, 2000; Torrey & Yolken, 1995; Yolken, Dickerson, & Torrey, 2009). Infectious parasites hosted by cats, Toxoplasma gondii (T. gondii), are transmitted through ingestion or inhalation of the parasite’s eggs that are shed with the infected cat’s feces into litter boxes, the yard, and elsewhere. For example, this could occur through hand-

Given these possible genetic, prenatal, and postnatal factors, what might be the organic problems that the person is predisposed to develop? There are two good answers—

Two psychedelic drugs, phencyclidine (PCP) and ketamine, have also provided some insight into the neurochemistry of schizophrenia (Julien, 2011). These two drugs produce schizophrenia-

Various structural brain abnormalities have also been found in people with schizophrenia, especially those suffering from Type II and chronic schizophrenia (Buchanan & Carpenter, 1997; Weyandt, 2006). I’ll mention a few. For example, brain scans of people with schizophrenia often indicate shrunken cerebral tissue and enlarged fluid-

vulnerability–

Even given all of this biological evidence, biopsychosocial explanations are necessary to explain all of the evidence accumulated about schizophrenia. A popular biopsychosocial explanation is the vulnerability–

In summary, there has been much research on the causes of schizophrenia, but we still do not have many clear answers. The only certainty is that schizophrenia is a disabling disorder with many causes. As pointed out in the DSM-

Personality Disorders

personality disorder A disorder characterized by inflexible, long-

A personality disorder is characterized by inflexible, long-

Personality disorders usually begin in childhood or adolescence and persist in a stable form throughout adulthood. It has been estimated that 9% to 13% of adults in the United States have a personality disorder (Comer, 2014). Personality disorders are fairly resistant to treatment and change. They need to be diagnosed, however, because they give the clinician a more complete understanding of the patient’s behavior and may complicate the treatment for a patient with another mental disorder. In addition, because the symptoms of the 10 personality disorders overlap so much, clinicians sometimes diagnose a person to have more than one personality disorder. This symptom overlap also leads clinicians to disagree about which personality disorder is the correct diagnosis, questioning the reliability of the DSM-

Section Summary

In this section, we discussed six major categories of mental disorders—

In obsessive-

Depressive disorders involve the presence of sad, empty, or irritable mood that impacts the individual’s capacity to function. The changes in the person’s emotional mood are excessive and unwarranted. The most common depressive disorder is major depressive disorder, which involves at least one major depressive episode. It is twice as frequent in women as in men. Sometimes this disorder is referred to as unipolar depression in order to contrast it with bipolar disorder, in which the person has recurrent cycles of depressive and manic (elevated mood) episodes. The concordance rate (the likelihood that one identical twin will get the disorder if the other twin has it) is substantial for both disorders, about 50% for depression and 70% for bipolar disorder. Neurotransmitter imbalances seem to be involved in both disorders, and cognitive factors are involved in major depressive disorder.

Schizophrenia is the most serious disorder discussed in this chapter. It is a psychotic disorder, which means that the person loses contact with reality. Clinicians divide schizophrenic symptoms into three categories—

Personality disorders are characterized by inflexible, long-

2

Question 10.3

.

Explain what is meant by the biopsychosocial approach and then describe a biopsychosocial explanation for specific phobic disorders.

A biopsychosocial explanation of a disorder entails explaining the problem as the result of the interaction of biological, psychological (behavioral and cognitive), and sociocultural factors. A good example is the explanation of specific phobia disorders in terms of a behavioral factor (classical conditioning) along with a biological predisposition to learn certain fears more easily. Thus, a psychological factor is involved in the learning of the fear but a biological factor determines which fears are easier to learn. Another good example is the vulnerability–

Question 10.4

.

Explain how the two anxiety disorders, specific phobia and generalized anxiety disorder, are different.

The anxiety and fear in a specific phobia disorder are exactly as the label indicates. They are specific to a certain class of objects or situations. However, the anxiety and fear in generalized anxiety disorder are not specific, but rather global. The person has excessive anxiety and worries most of the time, and the anxiety is not tied to anything in particular.

Question 10.5

.

Explain how the concordance rates for identical twins for a major depressive disorder and for schizophrenia indicate that more than biological causes are responsible for these disorders.

The concordance rates for identical twins for major depressive disorder and schizophrenia are only about 1 in 2 (50%). If only biological genetic factors were responsible for these disorders, these concordance rates would be 100%. Thus, psychological and sociocultural factors must play a role in causing these disorders.

Question 10.6

.

Explain the difference between schizophrenia and “split personality.”

Schizophrenia is a psychotic disorder. This means the person loses contact with reality. Thus, the split is between the person’s mental functions (perception, beliefs, and speech) and reality. In “split personality,” which used to be called multiple personality disorder and is now called dissociative identity disorder in the DSM-