America’s History: Printed Page 336

THINKING LIKE A HISTORIAN |  |

Becoming Literate: Public Education and Democracy

The struggle for a genuinely democratic polity — “government of the people, by the people, and for the people,” as Lincoln put it — played out at the local and state level in battles over who should participate in the political arena. As legislators argued over extending the franchise, they considered the knowledge that citizens needed to participate responsibly in politics. Although primary education was publicly supported in most New England towns (giving that region nearly universal literacy), it received only spotty funding in the other northern states and almost none in the South (restricting literacy there to one-third of the white population). The following documents address the resulting debate over publicly supported education and citizenship.

Editorial from the Philadelphia National Gazette, 1830. Pennsylvania was one of the first states to debate legislation regarding universal free public education.

The scheme of Universal Equal Education … is virtually “Agrarianism” [redistribution of land from rich to poor]. It would be a compulsory application of the means of the richer, for the direct use of the poorer classes. … One of the chief excitements to industry … is the hope of earning the means of educating their children respectably … that incentive would be removed, and the scheme of state and equal education be a premium for comparative idleness, to be taken out of the pockets of the laborious and conscientious.

Thaddeus Stevens, speech before the Pennsylvania General Assembly, February 1835. Pennsylvania’s Free Public School Act of 1834 was the handiwork of the Working Men’s Party of Philadelphia. When over half of Pennsylvania’s school districts refused to implement the law, the legislature threatened to repeal it. Thaddeus Stevens, later a leading antislavery advocate, turned back that threat through this speech to the Pennsylvania General Assembly.

It would seem to be humiliating to be under the necessity, in the nineteenth century, of entering into a formal argument to prove the utility, and to free governments, the absolute necessity of education. … Such necessity would be degrading to a Christian age and a free republic. If an elective republic is to endure for any great length of time, every elector must have sufficient information, not only to accumulate wealth and take care of his pecuniary concerns, but to direct wisely the Legislatures, the Ambassadors, and the Executive of the nation; for some part of all these things, some agency in approving or disapproving of them, falls to every freeman. If, then, the permanency of our government depends upon such knowledge, it is the duty of government to see that the means of information be diffused to every citizen. This is a sufficient answer to those who deem education a private and not a public duty — who argue that they are willing to educate their own children, but not their neighbor’s children.

“Letter from a Teacher” in Catharine E. Beecher, The True Remedy for the Wrongs of Women, 1851. The public school movement created new opportunities not just for children of middle and lower classes but also for the young Protestant women who contributed to the “Benevolent Empire” as professional educators. Beecher’s academy in Hartford, Connecticut, sent out dozens of young women to establish schools.

I am now located in this place, which is the county-town of a newly organized county [in a midwestern state]. … The Sabbath is little regarded, and is more a day for diversion than devotion. … My school embraces both sexes and all ages from five to seventeen, and not one can read intelligibly.

“Popular Education,” 1833. This piece appeared in the North American Review, the nation’s first literary and cultural journal and the mouthpiece of New England’s intellectual elite.

[T]he mind of a people, in proportion as it is educated, will not only feel its own value, but will also perceive its rights. We speak now of those palpable rights which are recognised by all free states. … [T]he palpable rights of men, those of personal security, of property and of the free and unembarrassed pursuit of individual welfare, it is obviously impossible to conceal from an educated and reading people. Such a people rises at once above the condition of feudal tenants. … It directs its attention to the laws and institutions that govern it. It compels public office to give an account of itself. It strips off the veil of secrecy from the machinery of power. … And when all this is spread abroad in newspaper details … of a people that can read; when the estimate is freely made, of what the government tax levies upon the daily hoard, and upon apparel, and upon every comfort of life, can it be doubted that such a people will demand and obtain an influence in affairs that so vitally concern it? This would be freedom.

Judge Baker, sentencing hearing in the court case against Mrs. Margaret Douglass of Norfolk, Virginia, January 10, 1854. Southern whites considered the acquisition of literacy by blacks, whether slave or free, as a public danger, especially after the Nat Turner uprising in Southampton County, Virginia, in 1831. A Virginia court sent Mrs. Margaret Douglass to jail for a month “as an example to all others” for teaching free black children to read so they might have access to books on religion and morality.

There are persons, I believe, in our community, opposed to the policy of the law in question. They profess to believe that universal intellectual culture is necessary to religious instruction and education, and that such culture is suitable to a state of slavery. …

Such opinions in the present state of our society I regard as manifestly mischievous. It is not true that our slaves cannot be taught religious and moral duty, without being able to read the Bible and use the pen. Intellectual and religious instruction often go hand in hand, but the latter may well be exist without the former; … among the whites one-fou[r]th or more are entirely without a knowledge of letters, [nonetheless,] respect for the law, and for moral and religious conduct and behavior, are justly and prope[r]ly appreciated and practiced. …

The first legislative provision upon this subject was introduced in the year 1831, immediately succeeding the bloody scenes of the memorable Southampton insurrection; and … was re-enacted with additional penalties in the year 1848. … After these several and repeated recognitions of the wisdom and propriety of the said act, it may well be said that bold and open opposition to it [must be condemned] … as a measure of self-preservation and protection.

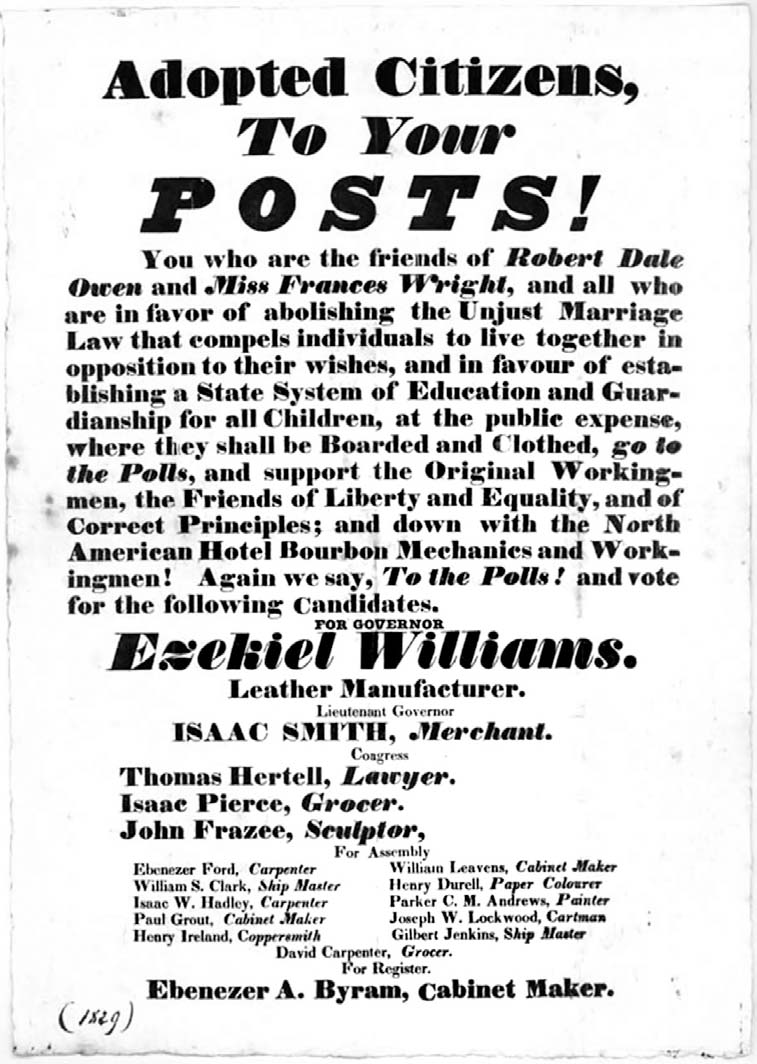

Working Men’s Party poster for immigrant voters, New York, 1830.

Source: Joshua R. Greenberg, Advocating the Man.

Source: Joshua R. Greenberg, Advocating the Man.

Sources: (1) “Religion and Social Reform,” the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, gilderlehrman.org; (2) New York Legislature Documents, Vol. 34, No. 65, Part 1 (Albany, NY: J. B. Lyon Company, 1919), 60; (3) Catharine E. Beecher, Educational Reminiscences and Suggestions (New York: J. D. Ford & Company, 1874), 127; (4) The North American Review 36, no. 58 (January 1833); (5) “The Case of Mrs. Margaret Douglass,” Africans in America, pbs.org.

ANALYZING THE EVIDENCE

Question

What arguments does the editorial in the Philadelphia National Gazette (source 1) advance? How does Stevens (source 2) reframe this argument?

Question

What does the letter from a former student of Beecher’s (source 3) tell us about the links between educational reform and other social movements, such as Sabbatarianism? How does it help us to understand the fate of the “notables” and the “log cabin campaign” of 1840?

Question

What is the larger agenda of the author of source 4? How is the argument here similar to, or different from, that in sources 1 and 2?

Question

How does Judge Baker (source 5) justify the denial of education to African Americans?

Question

What do the occupations of the Working Men’s Party candidates suggest about its definition of “worker” (source 6)? How does the political agenda of the party relate to the arguments advanced in sources 2 and 4? To present-day debates regarding the education of illegal immigrants?

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

Question

As these selections indicate, the debate over education had many facets. Did the power traditionally held by “notables” rest on their access to private schooling? Should a democratic society ensure the literacy of citizen voters? Was religious instruction a telling argument for slave literacy? Using these documents, your answers to the questions above, and materials in Chapters 8 and 10, write an essay that discusses public education, responsible citizenship, and social reform in America between 1820 and 1860.