America’s History: Printed Page 354

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 324

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 316

Urban Popular Culture

As utopians organized communities in the countryside, rural migrants and foreign immigrants created a new urban culture. In 1800, American cities were overgrown towns with rising death rates: New York had only 60,000 residents, Philadelphia had 41,000, and life expectancy at birth was a mere twenty-five years. Then urban growth accelerated as a huge in-migration outweighed the high death rates. By 1840, New York’s population had ballooned to 312,000; Philadelphia and its suburbs had 150,000 residents; and three other cities — New Orleans, Boston, and Baltimore — each had about 100,000. By 1860, New York had become a metropolis with more than 1 million residents: 813,000 in Manhattan and another 266,000 in the adjacent community of Brooklyn.

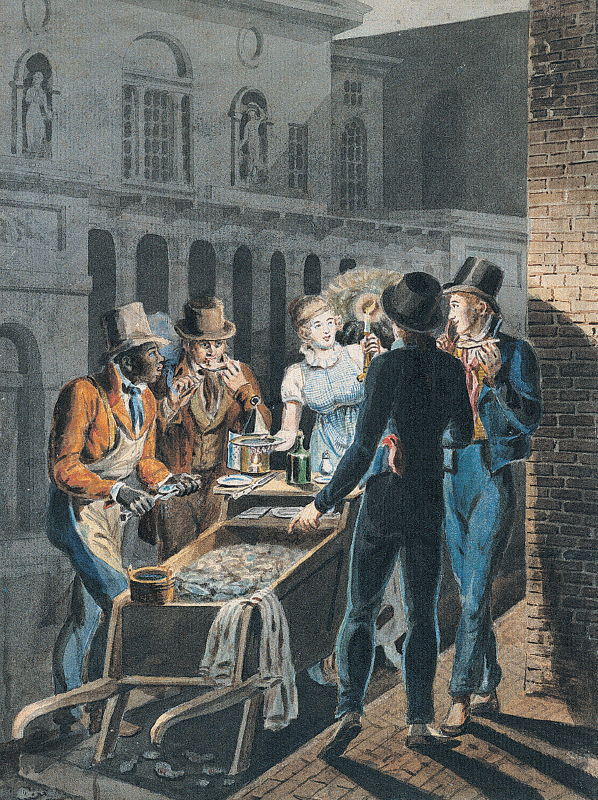

Sex in the City These newly populous cities, particularly New York, generated a new urban culture. Thousands of young men and women flocked to the city searching for adventure and fortune, but many found only a hard life. Young men labored for meager wages building thousands of tenements, warehouses, and workshops. Others worked as low-paid clerks or operatives in hundreds of mercantile and manufacturing firms. The young women had an even harder time. Thousands toiled as live-in domestic servants, ordered about by the mistress of the household and often sexually exploited by the master. Thousands more scraped out a bare living as needlewomen in New York City’s booming ready-made clothes industry. Unwilling to endure domestic service or subsistence wages, many young girls turned to prostitution. Dr. William Sanger’s careful survey, commissioned in 1855 by worried city officials, found six thousand women engaged in commercial sex. Three-fifths were native-born whites, and the rest were foreign immigrants; most were between fifteen and twenty years old. Half were or had been domestic servants, half had children, and half were infected with syphilis.

Commercialized sex — and sex in general — formed one facet of the new urban culture. “Sporting men” engaged freely in sexual conquests; otherwise respectable married men kept mistresses in handy apartments; and working men frequented bawdy houses. New York City had two hundred brothels in the 1820s and five hundred by the 1850s. Prostitutes — so-called “public” women — openly advertised their wares on Broadway, the city’s most fashionable thoroughfare, and welcomed clients on the infamous “Third Tier” of the theaters. Many men considered illicit sex as a right. “Man is endowed by nature with passions that must be gratified,” declared the Sporting Whip, a working-class magazine. Even the Reverend William Berrian, pastor of the ultra-respectable Trinity Episcopal Church, remarked from the pulpit that he had resorted ten times to “a house of ill-fame.”

Prostitution formed only the tip of the urban sexual volcano. Freed from family oversight, men formed homoerotic friendships and relationships; as early as 1800, the homosexual “Fop” was an acknowledged character in Philadelphia. Young people moved from partner to partner until they chanced on an ideal mate. Middle-class youth strolled along Broadway in the latest fashions: elaborate bonnets and silk dresses for young women; flowing capes, leather boots, and silver-plated walking sticks for young men. Rivaling the elegance on Broadway was the colorful dress on the Bowery, the broad avenue that ran along the east side of lower Manhattan. By day, the “Bowery Boy” worked as an apprentice or journeyman. By night, he prowled the streets as a “consummate dandy,” his hair cropped at the back of his head “as close as scissors could cut,” with long front locks “matted by a lavish application of bear’s grease, the ends tucked under so as to form a roll and brushed until they shone like glass bottles.” The “B’hoy,” as he was called, cut a dashing figure as he walked along with a “Bowery Gal” in a striking dress and shawl: “a light pink contrasting with a deep blue” or “a bright yellow with a brighter red.”

Minstrelsy Popular entertainment was a central facet of the new urban culture. In New York, workingmen could partake of traditional rural blood sports — rat and terrier fights as well as boxing matches — at Sportsmen Hall, or they could seek drink and fun in billiard and bowling saloons. Other workers crowded into the pit of the Bowery Theatre to see the “Mad Tragedian,” Junius Brutus Booth, deliver a stirring (abridged) performance of Shakespeare’s Richard III. Reform-minded couples enjoyed evenings at the huge Broadway Tabernacle, where they could hear an abolitionist lecture, see the renowned Hutchinson Family Singers lead a roof-raising rendition of their antislavery anthem, “Get Off the Track,” and sentimentally lament the separation of a slave couple in Stephen Foster’s “Oh Susanna,” a popular song of the late 1840s. Families could visit the museum of oddities (and hoaxes) created by P. T. Barnum, the great cultural entrepreneur and founder of the Barnum & Bailey Circus.

However, the most popular theatrical entertainments were the minstrel shows, in which white actors in blackface presented comic routines that combined racist caricature and social criticism. Minstrelsy began around 1830, when a few actors put on blackface and performed song-and-dance routines (Thinking Like a Historian). The most famous was John Dartmouth Rice, whose “Jim Crow” blended a weird shuffle-dance-and-jump with unintelligible lyrics delivered in “Negro dialect.” By the 1840s, there were hundreds of minstrel troupes, including a group of black entertainers, Gavitt’s Original Ethiopian Serenaders. The actor-singers’ rambling lyrics poked racist fun at African Americans, portraying them as lazy, sensual, and irresponsible while simultaneously using them to criticize white society. Minstrels ridiculed the drunkenness of Irish immigrants, parodied the halting English of German immigrants, denounced women’s demands for political rights, and mocked the arrogance of upper-class men. Still, by caricaturing blacks, the minstrels declared the importance of being white and spread racist sentiments among Irish and German immigrants.

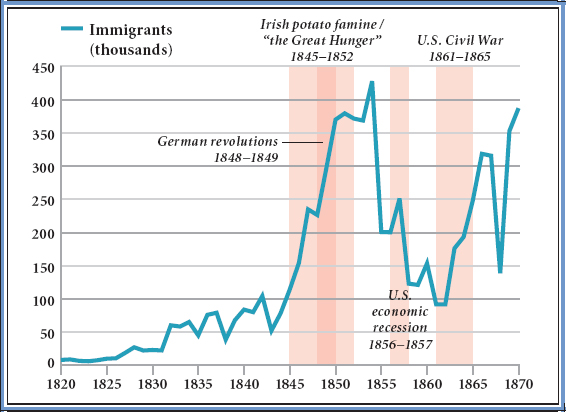

Immigrant Masses and Nativist Reaction By 1850, immigrants were a major presence throughout the Northeast. Irish men and women in New York City numbered 200,000, and Germans 110,000 (Figure 11.1). German-language shop signs filled entire neighborhoods, and German foods (sausages, hamburgers, sauerkraut) and food customs (such as drinking beer in family biergärten) became part of the city’s culture. The mass of impoverished Irish migrants found allies in the American Catholic Church, which soon became an Irish-dominated institution, and the Democratic Party, which gave them a foothold in the political process.

Native-born New Yorkers took alarm as hordes of ethnically diverse migrants altered the city’s culture. They organized a nativist movement — a final aspect of the new urban world. Beginning in the mid-1830s, nativists called for a halt to immigration and mounted a cultural and political assault on foreign-born residents. Gangs of B’hoys assaulted Irish youths in the streets, employers restricted Irish workers to the most menial jobs, and temperance reformers denounced the German fondness for beer. In 1844, the American Republican Party, with the endorsement of the Whigs, swept the city elections by focusing on the culturally emotional issues of temperance, anti-Catholicism, and nativism.

In the city, as in the countryside, new values were challenging old beliefs. The sexual freedom celebrated by Noyes at Oneida had its counterpart in commercialized sex and male promiscuity in New York City, where it came under attack from the Female Moral Reform Society. Similarly, the disciplined rejection of tobacco and alcohol by the Shakers and the Mormons found a parallel in the Washington Temperance Society and other urban reform organizations. American society was in ferment, and the outcome was far from clear.