America’s History: Printed Page 376

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 343

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 333

The South Expands:

Slavery and Society

1800–1860

12

CHAPTER

IDENTIFY THE BIG IDEA

How did the creation of a cotton-based economy change the lives of whites and blacks in all regions of the South?

Life in South Carolina had been good to James Lide. A slave-owning planter along the Pee Dee River, Lide and his wife raised twelve children and long resisted the “Alabama Fever” that prompted thousands of Carolinians to move west. Finally, at age sixty-five, probably seeking land for his many offspring, he moved his slaves and family — including six children and six grandchildren — to a plantation near Montgomery, Alabama. There, the family lived initially in a squalid log cabin with air holes but no windows. Even after building a new house, the Lides’ life remained unsettled. “Pa is quite in the notion of moving somewhere,” his daughter Maria reported. Although James Lide died in Alabama, many of his children moved on. In 1854, at the age of fifty-eight, Eli Lide migrated to Texas, telling his father, “Something within me whispers onward and onward.”

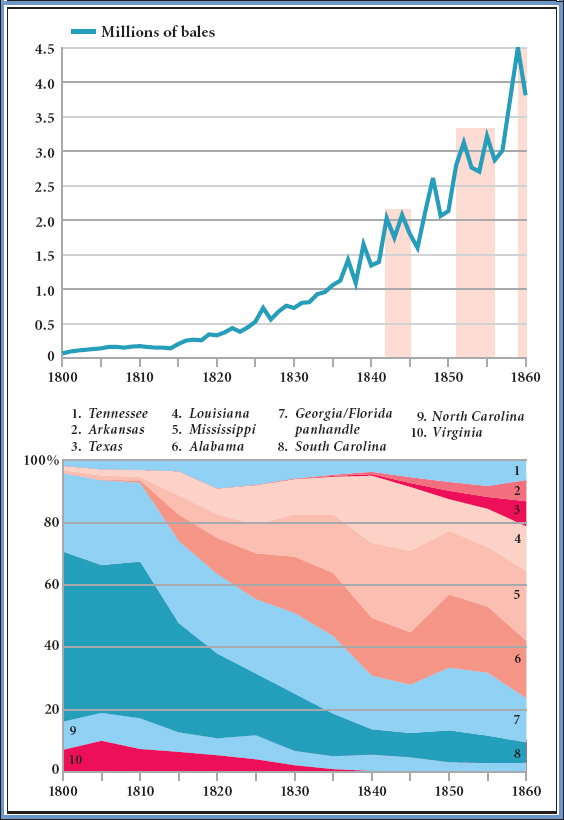

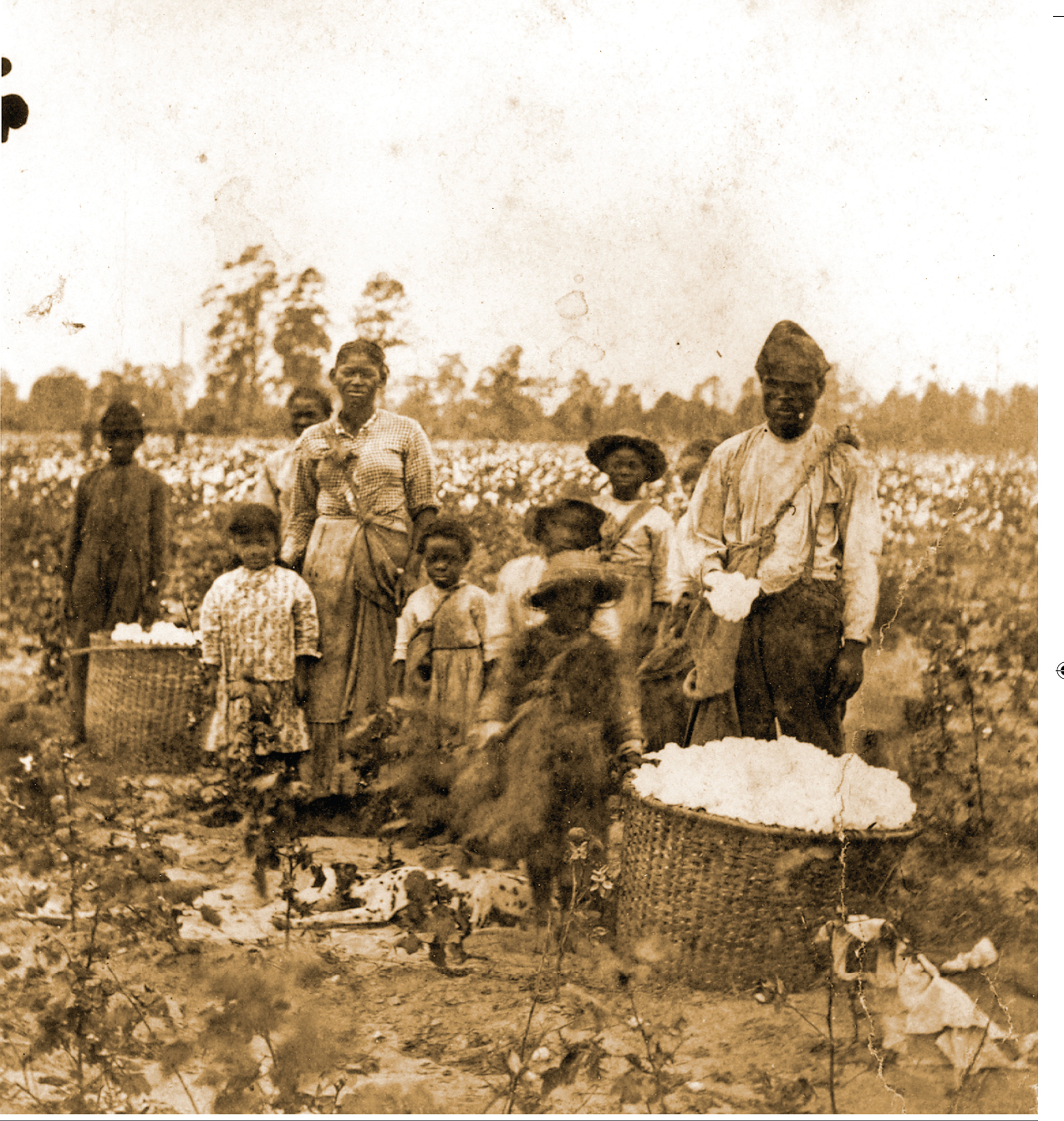

The Lides’ story was that of southern society. Between 1800 and 1860, white planters moved west and, using the muscles and sweat of a million enslaved African Americans, brought millions of acres into cultivation. By 1840, the South was at the cutting edge of the American Market Revolution (Figure 12.1). It annually produced and exported 1.5 million bales of raw cotton — over two-thirds of the world’s supply — and its economy was larger and richer than that of most nations. “Cotton is King,” boasted the Southern Cultivator.

No matter how rich they were, few cotton planters in Alabama, Mississippi, and Texas lived in elegant houses or led cultured lives. They had forsaken the aristocratic gentility of the Chesapeake and the Carolinas to make money. “To sell cotton in order to buy negroes — to make more cotton to buy more negroes, ‘ad infinitum,’ is the aim … of the thorough-going cotton planter,” a traveler reported from Mississippi in 1835. “His whole soul is wrapped up in the pursuit.” Plantation women lamented the loss of genteel surroundings and polite society. Raised in North Carolina, where she was “blest with every comfort, & even luxury,” Mary Drake found Mississippi and Alabama “a dreary waste.”

Enslaved African Americans knew what “dreary waste” really meant: unremitting toil, unrelieved poverty, and profound sadness. Sold south from Maryland, where his family had lived for generations, Charles Ball’s father became “gloomy and morose” and ran off and disappeared. With good reason: on new cotton plantations, slaves labored from “sunup to sundown” and from one end of the year to the other, forced to work by the threat of the lash. Always wanting more, southern planters and politicians plotted to extend their plantation economy across the continent.