America’s History: Printed Page 452

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 418

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 402

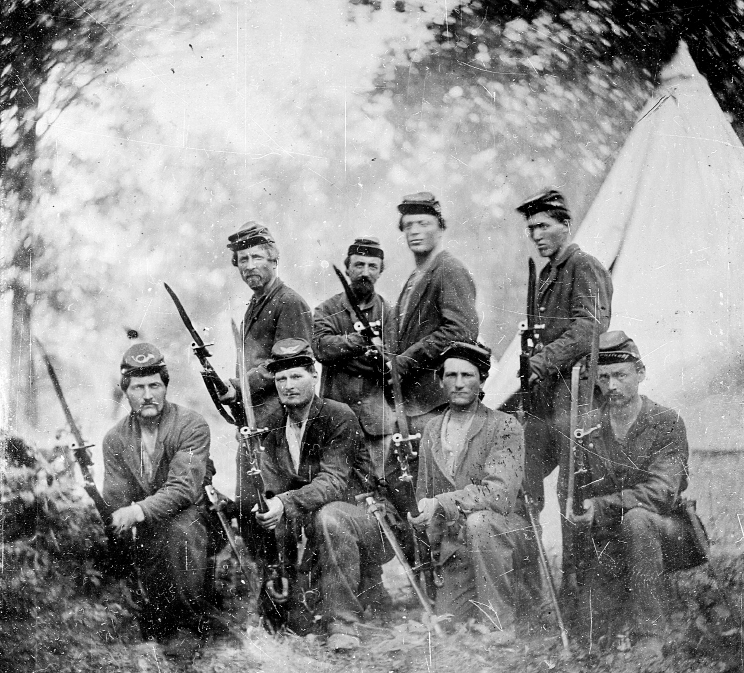

Mobilizing Armies and Civilians

Initially, patriotic fervor filled both armies with eager young volunteers. All he heard was “War! War! War!” one Union recruit recalled. Even those of sober minds joined up. “I don’t think a young man ever went over all the considerations more carefully than I did,” reflected William Saxton of Cincinnatus, New York. “It might mean sickness, wounds, loss of limb, and even life itself. … But my country was in danger.” The southern call for volunteers was even more successful, thanks to its strong military tradition and a culture that stressed duty and honor. “Would you, My Darling, … be willing to leave your Children under such a [despotic Union] government?” James B. Griffin of Edgefield, South Carolina, asked his wife. “No — I know you would sacrifice every comfort on earth, rather than submit to it.” However, enlistments declined as potential recruits learned the realities of mass warfare: epidemic diseases in the camps and wholesale death on the battlefields. Both governments soon faced the need for conscription.

The Military Draft The Confederacy acted first. In April 1862, following the bloodshed at Shiloh, the Confederate Congress imposed the first legally binding draft (conscription) in American history. New laws required existing soldiers to serve for the duration of the war and mandated three years of military service from all men between the ages of eighteen and thirty-five. In September 1862, after the heavy casualties at Antietam, the age limit jumped to forty-five. The South’s draft had two loopholes, both controversial. First, it exempted one white man — the planter, a son, or an overseer — for each twenty slaves, allowing some whites on large plantations to avoid military service. This provision, a Mississippi legislator warned Jefferson Davis, “has aroused a spirit of rebellion in some places.” Second, draftees could hire substitutes. By the time the Confederate Congress closed this loophole in 1864, the price of a substitute had soared to $300 in gold, three times the annual wage of a skilled worker. Laborers and yeomen farmers angrily complained that it was “a rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight.”

Consequently, some southerners refused to serve. Because the Confederate constitution vested sovereignty in the individual states, the government in Richmond could not compel military service. Independent-minded governors such as Joseph Brown of Georgia and Zebulon Vance of North Carolina simply ignored President Davis’s first draft call in early 1862. Elsewhere, state judges issued writs of habeas corpus — legal instruments used to protect people from arbitrary arrest — and ordered the Confederate army to release reluctant draftees. However, the Confederate Congress overrode the judges’ authority to free conscripted men, so the government was able to keep substantial armies in the field well into 1864.

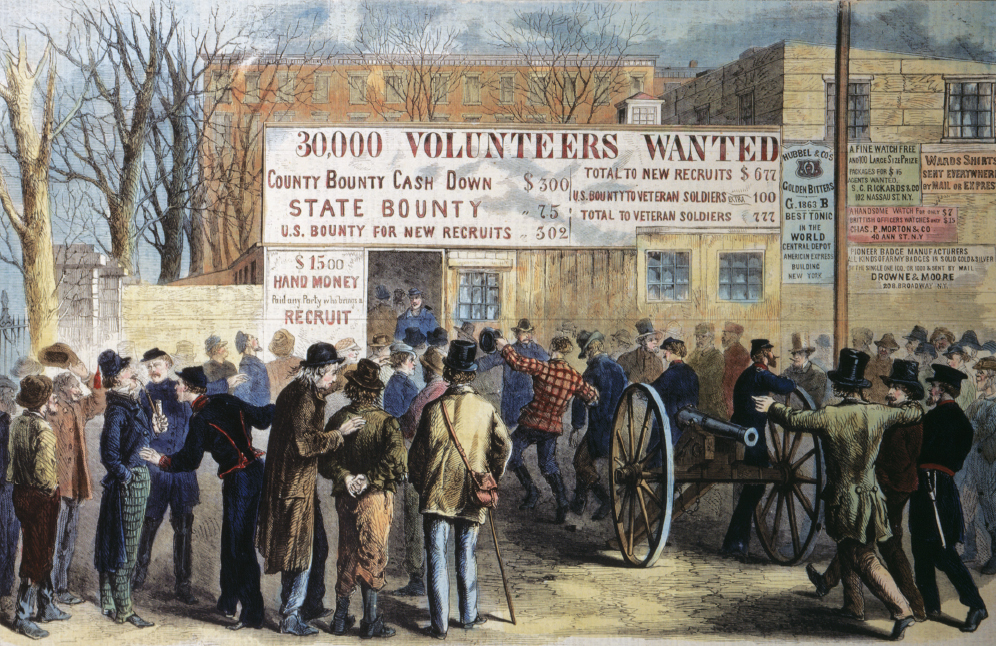

The Union government acted more ruthlessly toward draft resisters and Confederate sympathizers. In Missouri and other border states, Union commanders levied special taxes on southern supporters. Lincoln went further, suspending habeas corpus and, over the course of the war, temporarily imprisoning about 15,000 southern sympathizers without trial. He also gave military courts jurisdiction over civilians who discouraged enlistments or resisted the draft, preventing acquittals by sympathetic local juries. However, most Union governments used incentives to lure recruits. To meet the local quotas set by the Militia Act of 1862, towns, counties, and states used cash bounties of as much as $600 (about $11,000 today) and signed up nearly 1 million men. The Union also allowed men to avoid military service by providing a substitute or paying a $300 fee.

When the Enrollment Act of 1863 finally initiated conscription, recent German and Irish immigrants often refused to serve. It was not their war, they said. Northern Democrats used the furor over conscription to bolster support for their party, which increasingly criticized Lincoln’s policies. They accused Lincoln of drafting poor whites to liberate enslaved blacks, who would then flood the cities and take their jobs. Slavery was nearly “dead, [but] the negro is not, there is the misfortune,” declared a Democratic newspaper in Cincinnati. In July 1863, the immigrants’ hostility to conscription and blacks sparked riots in New York City. For five days, Irish and German workers ran rampant, burning draft offices, sacking the homes of influential Republicans, and attacking the police. The rioters lynched and mutilated a dozen African Americans, drove hundreds of black families from their homes, and burned down the Colored Orphan Asylum. To suppress the mobs, Lincoln rushed in Union troops who had just fought at Gettysburg; they killed more than a hundred rioters.

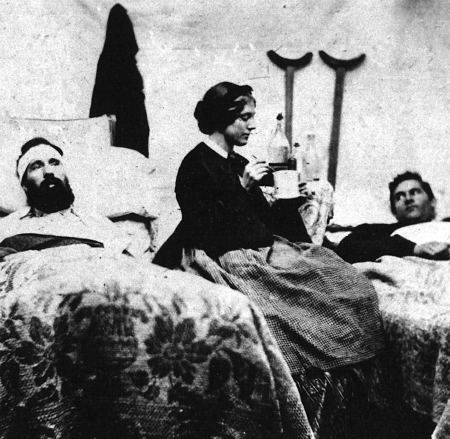

The Union government won much stronger support from native-born middle-class citizens. In 1861, prominent New Yorkers established the U.S. Sanitary Commission to provide the troops with clothing, food, and medical services. Seven thousand local auxiliaries assisted the commission’s work. “I almost weep,” reported a local agent, “when these plain rural people come to send their simple offerings to absent sons and brothers.” The commission also recruited battlefield nurses and doctors for the Union Army Medical Bureau. Despite these efforts, dysentery, typhoid, and malaria spread through the camps, as did mumps and measles, viruses that were often deadly to rural recruits. Diseases and infections killed about 250,000 Union soldiers, nearly twice the 135,000 who died in combat. Still, thanks to the Sanitary Commission, Union troops had a far lower mortality rate than soldiers fighting in nineteenth-century European wars. Confederate troops were less fortunate, despite the efforts of thousands of women who volunteered as nurses, because the Confederate army’s health system was poorly organized. Scurvy was a special problem for southern soldiers; lacking vitamin C in their diets, they suffered muscle ailments and had low resistance to camp diseases (Thinking Like a Historian).

So much death created new industries and cultural rituals. Embalmers devised a zinc chloride fluid to preserve soldiers’ bodies, allowing them to be shipped home for burial, an innovation that began modern funeral practices. Military cemeteries with hundreds of crosses in neat rows replaced the landscaped “rural cemeteries” in vogue in American cities before the Civil War. As thousands of mothers, wives, and sisters mourned the deaths of fallen soldiers, they faced changed lives. Confronting utter deprivation, working-class women grieved for the loss of a breadwinner. Middle-class wives often had financial resources but, having embraced the affectionate tenets of domesticity, mourned the death of a loved one by wearing black crape “mourning” dresses and other personal accessories of death. The destructive war, in concert with the emerging consumer culture and ethic of domesticity, produced a new “cult of mourning” among the middle and upper classes.

Women in Wartime As tens of thousands of wounded husbands and sons limped home, their wives and sisters helped them rebuild their lives. Another 200,000 women worked as volunteers in the Sanitary Commission and the Freedman’s Aid Society, which collected supplies for liberated slaves.

The war also drew more women into the wage-earning workforce as nurses, clerks, and factory operatives. Dorothea Dix served as superintendent of female nurses and, by successfully combating the prejudice against women providing medical treatment to men, opened a new occupation to women. Thousands of educated Union women became government clerks, while southern women staffed the efficient Confederate postal service. In both societies, millions of women took over farm tasks; filled jobs in schools and offices; and worked in textile, shoe, and food-processing factories. A few even became spies, scouts, and (disguising themselves as men) soldiers. As Union nurse Clara Barton, who later founded the American Red Cross, recalled, “At the war’s end, woman was at least fifty years in advance of the normal position which continued peace would have assigned her.”

PLACE EVENTS IN CONTEXT

Question

How did the Union and Confederacy mobilize their populations for war, and how effective were these methods?