America’s History: Printed Page 487

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 448

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 431

The Quest for Land

During the Civil War, wherever Union forces had conquered portions of the South, rural black workers had formed associations that agreed on common goals and even practiced military drills. After the war, when resettlement became the responsibility of the Freedmen’s Bureau, thousands of rural blacks hoped for land distributions. But Johnson’s amnesty plan, which allowed pardoned Confederates to recover property seized during the war, blasted such hopes. In October 1865, for example, Johnson ordered General Oliver O. Howard, head of the Freedmen’s Bureau, to restore plantations on South Carolina’s Sea Islands to white property holders. Dispossessed blacks protested: “Why do you take away our lands? You take them from us who have always been true, always true to the Government! You give them to our all-time enemies! That is not right!” Former slaves resisted efforts to evict them. Led by black Union veterans, they fought pitched battles with former slaveholders and bands of ex-Confederate soldiers. But white landowners, sometimes aided by federal troops, generally prevailed.

Freed Slaves and Northerners: Conflicting Goals On questions of land and labor, freedmen in the South and Republicans in Washington seriously differed. The economic revolution of the antebellum period had transformed New England and the Mid-Atlantic states. Believing similar development could revolutionize the South, most congressional leaders sought to restore cotton as the country’s leading export, and they envisioned former slaves as wageworkers on cash-crop plantations, not independent farmers. Only a handful of radicals, like Thaddeus Stevens, argued that freed slaves had earned a right to land grants, through what Lincoln had referred to as “four hundred years of unrequited toil.” Stevens proposed that southern plantations be treated as “forfeited estates of the enemy” and broken up into small farms for former slaves. “Nothing will make men so industrious and moral,” Stevens declared, “as to let them feel that they are above want and are the owners of the soil which they till.”

Today, most historians of Reconstruction agree with Stevens: policymakers did not do enough to ensure freedpeople’s economic security. Without land, former slaves were left poor and vulnerable. At the time, though, Stevens had few allies. A deep veneration for private property lay at the heart of his vision, but others interpreted the same principle differently: they defined ownership by legal title, not by labor invested. Though often accused of harshness toward the defeated Confederacy, most Republicans — even Radicals — could not imagine “giving” land to former slaves. The same congressmen, of course, had no difficulty giving away homesteads on the frontier that had been taken from Indians. But they were deeply reluctant to confiscate white-owned plantations.

Some southern Republican state governments did try, without much success, to use tax policy to break up large landholdings and get them into the hands of poorer whites and blacks. In 1869, South Carolina established a land commission to buy property and resell it on easy terms to the landless; about 14,000 black families acquired farms through the program. But such initiatives were the exception, not the rule. Over time, some rural blacks did succeed in becoming small-scale landowners, especially in Upper South states such as Virginia, North Carolina, and Tennessee. But it was an uphill fight, and policymakers provided little aid.

Wage Labor and Sharecropping Without land, most freedpeople had few options but to work for former slave owners. Landowners wanted to retain the old gang-labor system, with wages replacing the food, clothing, and shelter that slaves had once received. Southern planters — who had recently scorned the North for the cruelties of wage labor — now embraced wage work with apparent satisfaction. Maliciously comparing black workers to free-roaming pigs, landowners told them to “root, hog, or die.” Former slaves found themselves with rock-bottom wages; it was a shock to find that emancipation and “free labor” did not prevent a hardworking family from nearly starving.

African American workers used a variety of tactics to fight back. As early as 1865, alarmed whites across the South reported that former slaves were holding mass meetings to agree on “plans and terms for labor.” Such meetings continued through the Reconstruction years. Facing limited prospects at home, some workers left the fields and traveled long distances to seek better-paying jobs on the railroads or in turpentine and lumber camps. Others — from rice cultivators to laundry workers — organized strikes.

At the same time, struggles raged between employers and freedpeople over women’s work. In slavery, African American women’s bodies had been the sexual property of white men. Protecting black women from such abuse, as much as possible, was a crucial priority for freedpeople. When planters demanded that black women go back into the fields, African Americans resisted resolutely. “I seen on some plantations,” one freedman recounted, “where the white men would … tell colored men that their wives and children could not live on their places unless they work in the fields. The colored men [answered that] whenever they wanted their wives to work they would tell them themselves.”

There was a profound irony in this man’s definition of freedom: it designated a wife’s labor as her husband’s property. Some black women asserted their independence and headed their own households, though this was often a matter of necessity rather than choice. For many freedpeople, the opportunity for a stable family life was one of the greatest achievements of emancipation. Many enthusiastically accepted the northern ideal of domesticity. Missionaries, teachers, and editors of black newspapers urged men to work diligently and support their families, and they told women (though many worked for wages) to devote themselves to motherhood and the home.

Even in rural areas, former slaves refused to work under conditions that recalled slavery. There would be no gang work, they vowed: no overseers, no whippings, no regulation of their private lives. Across the South, planters who needed labor were forced to yield to what one planter termed the “prejudices of the freedmen, who desire to be masters of their own time.” In a few areas, wage work became the norm — for example, on the giant sugar plantations of Louisiana financed by northern capital. But cotton planters lacked money to pay wages, and sometimes, in lieu of a wage, they offered a share of the crop. Freedmen, in turn, paid their rent in shares of the harvest.

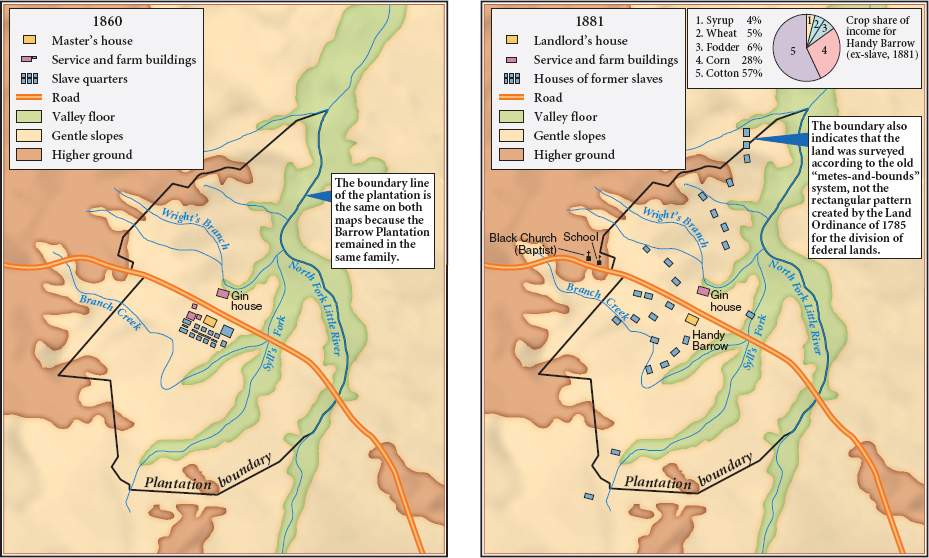

Thus the Reconstruction years gave rise to a distinctive system of cotton agriculture known as sharecropping, in which freedmen worked as renters, exchanging their labor for the use of land, house, implements, and sometimes seed and fertilizer. Sharecroppers typically turned over half of their crops to the landlord (Map 15.2). In a credit-starved agricultural region that grew crops for a world economy, sharecropping was an effective strategy, enabling laborers and landowners to share risks and returns. But it was a very unequal relationship. Starting out penniless, sharecroppers had no way to make it through the first growing season without borrowing for food and supplies.

Country storekeepers stepped in. Bankrolled by northern suppliers, they furnished sharecroppers with provisions and took as collateral a lien on the crop, effectively assuming ownership of croppers’ shares and leaving them only what remained after debts had been paid. Crop-lien laws enforced lenders’ ownership rights to the crop share. Once indebted at a store, sharecroppers became easy targets for exorbitant prices, unfair interest rates, and crooked bookkeeping. As cotton prices declined in the 1870s, more and more sharecroppers fell into permanent debt. If the merchant was also the landowner or conspired with the landowner, debt became a pretext for forced labor, or peonage.

Sharecropping arose in part because it was a good fit for cotton agriculture. Cotton, unlike sugarcane, could be raised efficiently by small farmers (provided they had the lash of indebtedness always on their backs). We can see this in the experience of other regions that became major producers in response to the global cotton shortage set off by the Civil War. In India, Egypt, Brazil, and West Africa, variants of the sharecropping system emerged. Everywhere international merchants and bankers, who put up capital, insisted on passage of crop-lien laws. Indian and Egyptian villagers ended up, like their American counterparts, permanently under the thumb of furnishing merchants.

By 1890, three out of every four black farmers in the South were tenants or sharecroppers; among white farmers, the ratio was one in three. For freedmen, sharecropping was not the worst choice, in a world where former masters threatened to impose labor conditions that were close to slavery. But the costs were devastating. With farms leased on a year-to-year basis, neither tenant nor owner had much incentive to improve the property. The crop-lien system rested on expensive interest payments — money that might otherwise have gone into agricultural improvements or to meet human needs. And sharecropping committed the South inflexibly to cotton, a crop that generated the cash required by landlords and furnishing merchants. The result was a stagnant farm economy that blighted the South’s future. As Republican governments tried to remake the region, they confronted not only wartime destruction but also the failure of their hopes that free labor would create a modern, prosperous South, built in the image of the industrializing North. Instead, the South’s rural economy remained mired in widespread poverty and based on an uneasy compromise between landowners and laborers.

IDENTIFY CAUSES

Question

Why did sharecropping emerge, and how did it affect freedpeople and the southern economy?