America’s History: Printed Page 557

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 509

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 493

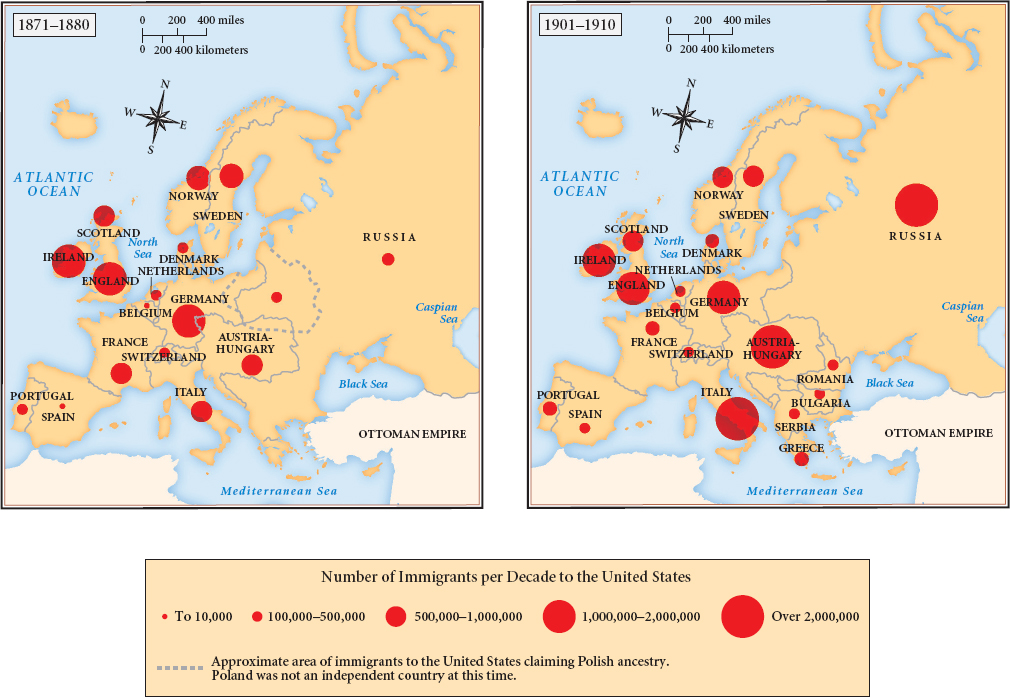

Newcomers from Europe

Mass migration from Western Europe had started in the 1840s, when more than one million Irish fled a terrible famine. In the following decades, as Europe’s population grew rapidly and agriculture became commercialized, peasant economies suffered, first in Germany and Scandinavia, then across Austria-Hungary, Russia, Italy, and the Balkans. This upheaval displaced millions of rural people. Some went to Europe’s mines and factories; others headed for South America and the United States (Map 17.2; America Compared).

“America was known to foreigners,” remembered one Jewish woman from Lithuania, “as the land where you’d get rich.” But the reality was much harsher. Even in the age of steam, a transatlantic voyage was grueling. For ten to twenty days, passengers in steerage class crowded belowdecks, eating terrible food and struggling with seasickness. An investigator who traveled with immigrants from Naples asked, “How can a steerage passenger remember that he is a human being when he must first pick the worms from his food?” After 1892, European immigrants were routed through the enormous receiving station at New York’s Ellis Island.

Some immigrants brought skills. Many Welshmen, for example, arrived in the United States as experienced tin-plate makers; Germans came as machinists and carpenters, Scandinavians as sailors. But industrialization required, most of all, increasing quantities of unskilled labor. As poor farmers from Italy, Greece, and Eastern Europe arrived in the United States, heavy, low-paid labor became their domain.

In an era of cheap railroad and steamship travel, many immigrants expected to work and save for a few years and then head home. More than 800,000 French Canadians moved to New England in search of textile jobs, many families with hopes of scraping together enough savings to return to Quebec and buy a farm. Thousands of men came alone, especially from Ireland, Italy, and Greece. Many single Irishwomen also immigrated. But some would-be sojourners ended up staying a lifetime, while immigrants who had expected to settle permanently found themselves forced to leave by an accident or sudden economic depression. One historian has estimated that a third of immigrants to the United States in this era returned to their home countries.

Along with Italians and Greeks, Eastern European Jews were among the most numerous arrivals. The first American Jews, who numbered around 50,000 in 1880, had been mostly of German-Jewish descent. In the next four decades, more than 3 million poverty-stricken Jews arrived from Russia, Ukraine, Poland, and other parts of Eastern Europe, transforming the Jewish presence in the United States. Like other immigrants, they sought economic opportunity, but they also came to escape religious repression (American Voices).

Wherever they came from, immigrants took a considerable gamble in traveling to the United States. Some prospered quickly, especially if they came with education, money, or well-placed business contacts. Others, by toiling many years in harsh conditions, succeeded in securing a better life for their children or grandchildren. Still others met with catastrophe or early death. One Polish man who came with his parents in 1908 summed up his life over the next thirty years as “a mere struggle for bread.” He added: “Sometimes I think life isn’t worth a damn for a man like me. … Look at my wife and kids — undernourished, seldom have a square meal.” But an Orthodox Russian Jewish woman told an interviewer that she “thanked God for America,” where she had married, raised three children, and made a good life. She “liked everything about this country, especially its leniency toward the Jews.”

UNDERSTAND POINTS OF VIEW

Question

What factors accounted for the different expectations and experiences of immigrants in this era?