America’s History: Printed Page 560

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 511

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 495

Asian Americans and Exclusion

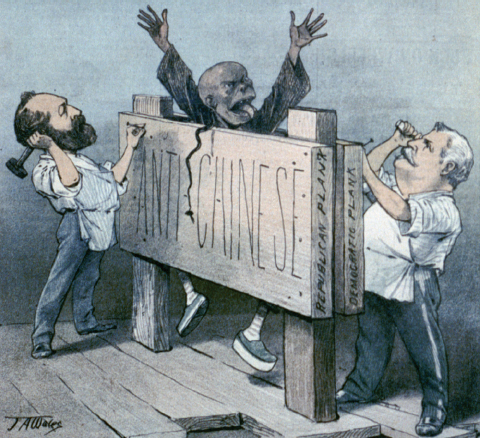

Compared with Europeans, newcomers from Asia faced even harsher treatment. The first Chinese immigrants had arrived in the late 1840s during the California gold rush. After the Civil War, the Burlingame Treaty between the United States and China opened the way for increasing numbers to emigrate. Fleeing poverty and upheaval in southern China, they, like European immigrants, filled low-wage jobs in the American economy. The Chinese confronted threats and violence. “We kept indoors after dark for fear of being shot in the back,” remembered one Chinese immigrant to California. During the depression of the 1870s, a rising tide of racism was especially extreme in the Pacific coast states, where the majority of Chinese immigrants lived. “The Chinese must go!” railed Dennis Kearney, leader of the California Workingmen’s Party, who referred to Asians as “almond-eyed lepers.” Incited by Kearney in July 1877, a mob burned San Francisco’s Chinatown and beat up residents. In the 1885 Rock Springs massacre in Wyoming, white men burned the local Chinatown and murdered at least twenty-eight Chinese miners.

Despite such atrocities, some Chinese managed to build profitable businesses and farms. Many did so by filling the only niches native-born Americans left open to them: running restaurants and laundries. Facing intense political pressure, Congress in 1882 passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, specifically barring Chinese laborers from entering the United States. Each decade thereafter, Congress renewed the law and tightened its provisions; it was not repealed until 1943. Exclusion barred almost all Chinese women, forcing husbands and wives to spend many years apart when men took jobs in the United States.

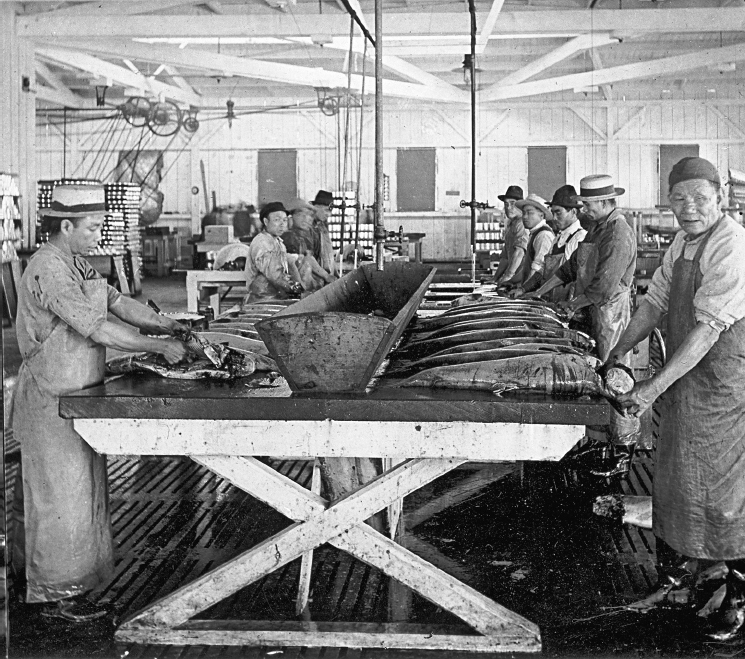

Asian immigrants made vigorous use of the courts to try to protect their rights. In a series of cases brought by Chinese and later Japanese immigrants, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that all persons born in the United States had citizenship rights that could not be revoked, even if their parents had been born abroad. Nonetheless, well into the twentieth century, Chinese immigrants (as opposed to native-born Chinese Americans) could not apply for citizenship. Meanwhile, Japanese and a few Korean immigrants also began to arrive; by 1909, there were 40,000 Japanese immigrants working in agriculture, 10,000 on railroads, and 4,000 in canneries. In 1906, the U.S. attorney general ruled that Japanese and Koreans, like Chinese immigrants, were barred from citizenship.

The Chinese Exclusion Act created the legal foundations on which far-reaching exclusionary policies would be built in the 1920s and after. To enforce the law, Congress and the courts gave sweeping new powers to immigration officials, transforming the Chinese into America’s first illegal immigrants. Drawn, like others, by the promise of jobs in America’s expanding economy, Chinese men stowed away on ships or walked across the borders. Disguising themselves as Mexicans — who at that time could freely enter the United States — some perished in the desert as they tried to reach California.

Some would-be immigrants, known as paper sons, relied on Chinese residents in the United States, who generated documents falsely claiming the newcomers as American-born children. Paper sons memorized pages of information about their supposed relatives and hometowns. The San Francisco earthquake of 1906 helped their cause by destroying all the port’s records. “That was a big chance for a lot of Chinese,” remembered one immigrant. “They forged themselves certificates saying they could go back to China and bring back four or five sons, just like that!” Such persistence ensured that, despite the harsh policies of Chinese exclusion, the flow of Asian immigrants never fully ceased.