America’s History: Printed Page 569

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 520

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 503

Another Path: The American Federation of Labor

While the Knights of Labor exerted political pressure, other workers pursued a different strategy. In the 1870s, printers, ironworkers, bricklayers, and other skilled workers organized nationwide trade unions. These “brotherhoods” focused on the everyday needs of workers in skilled occupations. Trade unions sought a closed shop — with all jobs reserved for union members — that kept out lower-wage workers. Union rules specified terms of work, sometimes in minute detail. Many unions emphasized mutual aid. Because working on the railroads was a high-risk occupation, for example, brotherhoods of engineers, brakemen, and firemen pooled contributions into funds that provided accident and death benefits. Above all, trade unionism asserted craft workers’ rights as active decision-makers in the workplace, not just cogs in a management-run machine.

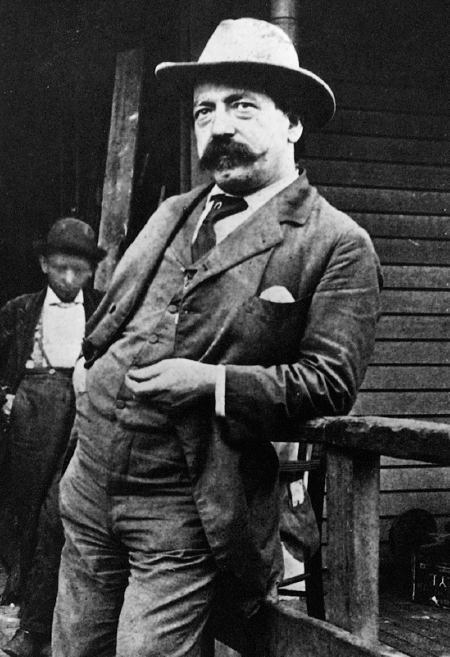

In the early 1880s, many trade unionists joined the Knights of Labor coalition. But the aftermath of the Haymarket violence persuaded them to leave and create the separate American Federation of Labor (AFL). The man who led them was Samuel Gompers, a Dutch-Jewish cigar maker whose family had emigrated to New York in 1863. Gompers headed the AFL for the next thirty years. He believed the Knights relied too much on electoral politics, where victories were likely to be limited, and he did not share their sweeping critique of capitalism. The AFL, made up of relatively skilled and well-paid workers, was less interested in challenging the corporate order than in winning a larger share of its rewards.

Having gone to work at age ten, Gompers always contended that what he missed at school he more than made up for in the shop, where cigar makers paid one of their members to read to them while they worked. As a young worker-intellectual, Gompers gravitated to New York’s radical circles, where he participated in lively debates about which strategies workingmen should pursue. Partly out of these debates, and partly from his own experience in the Cigar Makers Union, Gompers hammered out a doctrine that he called pure-and-simple unionism. Pure referred to membership: strictly limited to workers, organized by craft and occupation, with no reliance on outside advisors or allies. Simple referred to goals: only those that immediately benefitted workers — better wages, hours, and working conditions. Pure-and-simple unionists distrusted politics. Their aim was collective bargaining with employers.

On one level, pure-and-simple unionism worked. The AFL was small at first, but by 1904 its membership rose to more than two million. In the early twentieth century, it became the nation’s leading voice for workers, lasting far longer than movements like the Knights of Labor. The AFL’s strategy — personified by Gompers — was well suited to an era when Congress and the courts were hostile to labor. By the 1910s, the political climate would become more responsive; at that later moment, Gompers would soften his antipolitical stance and join the battle for new labor laws.

What Gompers gave up most crucially, in the meantime, was the inclusiveness of the Knights. By comparison, the AFL was far less welcoming to women and blacks; it included mostly skilled craftsmen. There was little room in the AFL for department-store clerks and other service workers, much less the farm tenants and domestic servants whom the Knights had organized. Despite the AFL’s success among skilled craftsmen, the narrowness of its base was a problem that would come back to haunt the labor movement later on. Gompers, however, saw that corporate titans and their political allies held tremendous power, and he advocated what he saw as the most practical defensive plan. In the meantime, the upheaval wrought by industrialization spread far beyond the workplace, transforming every aspect of American life.

TRACE CHANGE OVER TIME

Question

How did the key institutions and goals of the labor movement change, and what gains and losses resulted from this shift?