America’s History: Printed Page 546

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 500

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 484

Innovators in Enterprise

As rail lines stretched westward between the 1850s and 1880s, operators faced a crisis. As one Erie Railroad executive noted, a superintendent on a 50-mile line could personally attend to every detail. But supervising a 500-mile line was impossible; trains ran late, communications failed, and trains crashed. Managers gradually invented systems to solve these problems. They distinguished top executives from those responsible for day-to-day operations. They departmentalized operations by function — purchasing, machinery, freight traffic, passenger traffic — and established clear lines of communication. They perfected cost accounting, which allowed an industrialist like Carnegie to track expenses and revenues carefully and thus follow his Scottish mother’s advice: “Take care of the pennies, and the pounds will take care of themselves.” This management revolution created the internal structure adopted by many large, complex corporations.

During these same years, the United States became an industrial power by tapping North America’s vast natural resources, particularly in the West. Industries that had once depended on water power began to use prodigious amounts of coal. Steam engines replaced human and animal labor, and kerosene replaced whale oil and wood. By 1900, America’s factories and urban homes were converting to electric power. With new management structures and dependency on fossil fuels (oil, coal, natural gas), corporations transformed both the economy and the country’s natural and built environments.

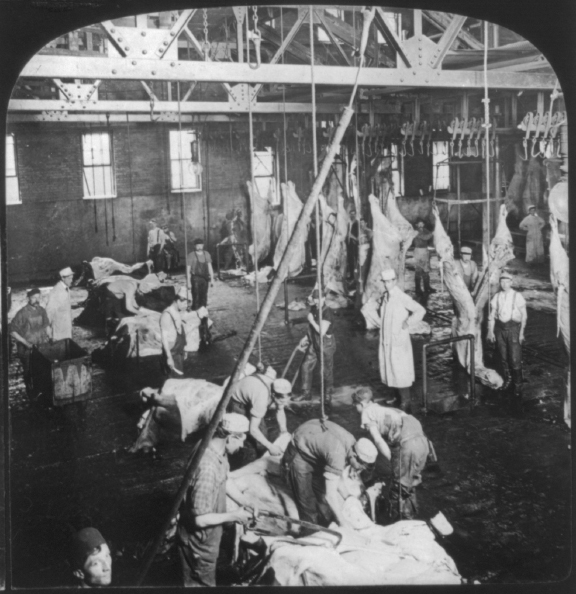

Production and Sales After Chicago’s Union Stock Yards opened in 1865, middlemen shipped cows by rail from the Great Plains to Chicago and from there to eastern cities, where slaughter took place in local butchertowns. Such a system — a national livestock market with local processing — could have lasted, as it did in Europe. But Gustavus Swift, a shrewd Chicago cattle dealer, saw that local slaughterhouses lacked the scale to utilize waste by-products and cut labor costs. To improve productivity, Swift invented the assembly line, where each wageworker repeated the same slaughtering task over and over.

Swift also pioneered vertical integration, a model in which a company controlled all aspects of production from raw materials to finished goods. Once his engineers designed a cooling system, Swift invested in a fleet of refrigerator cars to keep beef fresh as he shipped it eastward, priced below what local butchers could afford. In cities that received his chilled meat, Swift built branch houses and fleets of delivery wagons. He also constructed factories to make fertilizer and chemicals from the by-products of slaughter, and he developed marketing strategies for those products as well. Other Chicago packers followed Swift’s lead. By 1900, five firms, all vertically integrated, produced nearly 90 percent of the meat shipped in interstate commerce.

Big packers invented new sales tactics. For example, Swift & Company periodically slashed prices in certain markets to below production costs, driving independent distributors to the wall. With profits from its sales elsewhere, a large firm like Swift could survive temporary losses in one locality until competitors went under. Afterward, Swift could raise prices again. This technique, known as predatory pricing, helped give a few firms unprecedented market control.

Standard Oil and the Rise of the Trusts No one used ruthless business tactics more skillfully than the king of petroleum, John D. Rockefeller. After inventors in the 1850s figured out how to extract kerosene — a clean-burning fuel for domestic heating and lighting — from crude oil, enormous oil deposits were discovered at Titusville, Pennsylvania. Just then, the Civil War severely disrupted whaling, forcing whale-oil customers to look for alternative lighting sources. Overnight, a forest of oil wells sprang up around Titusville. Connected to these Pennsylvania oil fields by rail in 1863, Cleveland, Ohio, became a refining center. John D. Rockefeller was then an up-and-coming Cleveland grain dealer. (He, like Carnegie and most other budding tycoons, hired a substitute to fight for him in the Civil War.) Rockefeller had strong nerves, a sharp eye for able partners, and a genius for finance. He went into the kerosene business and borrowed heavily to expand. Within a few years, his firm — Standard Oil of Ohio — was Cleveland’s leading refiner.

Like Carnegie and Swift, Rockefeller succeeded through vertical integration: to control production and sales all the way from the oil well to the kerosene lamp, he took a big stake in the oil fields, added pipelines, and developed a vast distribution network. Rockefeller allied with railroad executives, who, like him, hated the oil market’s boom-and-bust cycles. What they wanted was predictable, high-volume traffic, and they offered Rockefeller secret rebates that gave him a leg up on competitors.

Rockefeller also pioneered a strategy called horizontal integration. After driving competitors to the brink of failure through predatory pricing, he invited them to merge their local companies into his conglomerate. Most agreed, often because they had no choice. Through such mergers, Standard Oil wrested control of 95 percent of the nation’s oil refining capacity by the 1880s. In 1882, Rockefeller’s lawyers created a new legal form, the trust. It organized a small group of associates — the board of trustees — to hold stock from a group of combined firms, managing them as a single entity. Rockefeller soon invested in Mexican oil fields and competed in world markets against Russian and Middle Eastern producers.

Other companies followed Rockefeller’s lead, creating trusts to produce such products as linseed oil, sugar, and salt. Many expanded sales and production overseas. As early as 1868, Singer Manufacturing Company established a factory in Scotland to produce sewing machines. By World War I, such brands as Ford and General Electric had become familiar around the world.

Distressed by the development of near monopolies, reformers began to denounce “the trusts,” a term that in popular usage referred to any large corporation that seemed to wield excessive power. Some states outlawed trusts as a legal form. But in an effort to attract corporate headquarters to its state, New Jersey broke ranks in 1889, passing a law that permitted the creation of holding companies and other combinations. Delaware soon followed, providing another legal haven for consolidated corporations. A wave of mergers further concentrated corporate power during the depression of the 1890s, as weaker firms succumbed to powerful rivals. By 1900, America’s largest one hundred companies controlled a third of the nation’s productive capacity. Purchasing several steel companies in 1901, including Carnegie Steel, J. P. Morgan created U.S. Steel, the nation’s first billion-dollar corporation. Such familiar firms as DuPont and Eastman Kodak assumed dominant places in their respective industries.

Assessing the Industrialists The work of men like Swift, Rockefeller, and Carnegie was controversial in their lifetimes and has been ever since. Opinions have tended to be harsh in eras of economic crisis, when the shortcomings of corporate America appear in stark relief. During the Great Depression of the 1930s, a historian coined the term robber barons, which is still used today. In periods of prosperity, both scholars and the public have tended to view early industrialists more favorably, calling them industrial statesmen.

Some historians have argued that industrialists benefitted the economy by replacing the chaos of market competition with a “visible hand” of planning and expert management. But one recent study of railroads asserts that the main skills of early tycoons (as well as those of today) were cultivating political “friends,” defaulting on loans, and lying to the public. Whether we consider the industrialists heroes, villains, or something in between, it is clear that the corporate economy was not the creation of just a few individuals, however famous or influential. It was a systemic transformation of the economy.

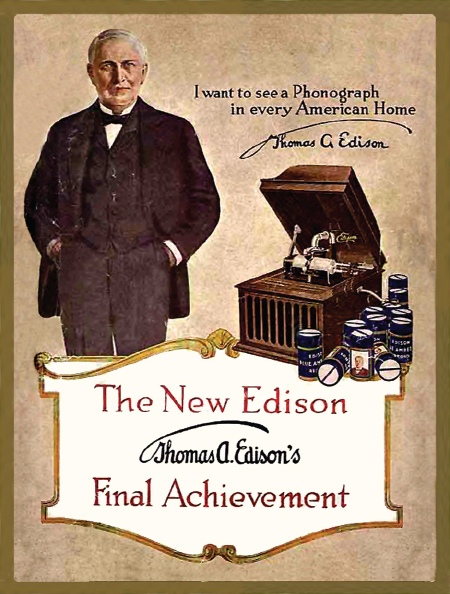

A National Consumer Culture As they integrated vertically and horizontally, corporations innovated in other ways. Companies such as Bell Telephone and Westinghouse set up research laboratories. Steelmakers invested in chemistry and materials science to make their products cheaper, better, and stronger. Mass markets brought an appealing array of goods to consumers who could afford them. Railroads whisked Florida oranges and other fresh produce to the shelves of grocery stores. Retailers such as F. W. Woolworth and the Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company (A&P) opened chains of stores that soon stretched nationwide.

The department store was pioneered in 1875 by John Wanamaker in Philadelphia. These megastores displaced small retail shops, tempting customers with large show windows and Christmas displays. Like industrialists, department store magnates developed economies of scale that enabled them to slash prices. An 1898 newspaper advertisement for Macy’s Department Store urged shoppers to “read our books, cook in our saucepans, dine off our china, wear our silks, get under our blankets, smoke our cigars, drink our wines — Shop at Macy’s — and Life will Cost You Less and Yield You More Than You Dreamed Possible.”

While department stores became urban fixtures, Montgomery Ward and Sears built mail-order empires. Rural families from Vermont to California pored over the companies’ annual catalogs, making wish lists of tools, clothes, furniture, and toys. Mail-order companies used money-back guarantees to coax wary customers to buy products they could not see or touch. “Don’t be afraid to make a mistake,” the Sears catalog counseled. “Tell us what you want, in your own way.” By 1900, America counted more than twelve hundred mail-order companies.

The active shaping of consumer demand became, in itself, a new enterprise. Outdoors, advertisements appeared everywhere: in New York’s Madison Square, the Heinz Company installed a 45-foot pickle made of green electric lights. Tourists had difficulty admiring Niagara Falls because billboards obscured the view. By 1900, companies were spending more than $90 million a year ($2.3 billion today) on print advertising, as the press itself became a mass-market industry. Rather than charging subscribers the cost of production, magazines began to cover their costs by selling ads. Cheap subscriptions built a mass readership, which in turn attracted more advertisers. In 1903, the Ladies’ Home Journal became the first magazine with a million subscribers.

IDENTIFY CAUSES

Question

Why did large corporations arise in the late nineteenth century, and how did leading industrialists consolidate their power?