America’s History: Printed Page 554

THINKING LIKE A HISTORIAN |  |

Poverty and Food

Amid rising industrial poverty, food emerged as a reference point. How much was too little, or too much? If some Americans were going hungry, how should others respond? The documents below show some contributions to these debates.

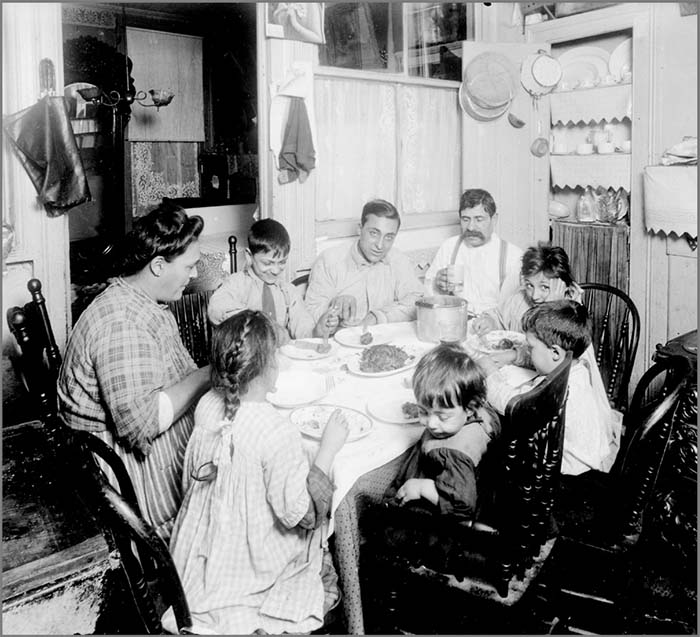

Lewis W. Hine, “Mealtime, New York Tenement,” 1910. Hine was an influential photographer and reformer. He took a famous series of photographs at Ellis Island, remarking that he hoped Americans would view new immigrants in the same way they thought of the Pilgrims. What does the photographer emphasize in the living conditions of this Italian immigrant family and their relationships with one another? Why do you think Hine photographed them at the table?

George Eastman House.

George Eastman House.Louisa May Alcott, Little Women, 1869. Alcott’s novel, popular for decades, exemplified the ideal of Christian charity. At the start of this scene, Mrs. March returns from a Christmas morning expedition.

Merry Christmas, little daughters!… I want to say one word before we sit down [to breakfast]. Not far away from here lies a poor woman with a little newborn baby. Six children are huddled into one bed to keep from freezing, for they have no fire. There is nothing to eat. … My girls, will you give them your breakfasts as a Christmas present?

… For a minute no one spoke, only a minute, for Jo exclaimed impetuously, I’m so glad you came before we began!

May I go and help… ? asked Beth eagerly.

I shall take the cream and the muffins, added Amy. … Meg was already covering the buckwheats and piling the bread into one big plate.

I thought you’d do it, said Mrs. March, smiling.

… A poor, bare, miserable room it was, with broken windows, no fire, ragged bedclothes, a sick mother, wailing baby, and a group of pale, hungry children. … Mrs. March gave the mother tea and gruel [while] the girls meantime spread the table [and] set the children round the fire. …

That was a very happy breakfast, though they didn’t get any of it. And when they went away, leaving comfort behind, I think there were not in all the city four merrier people than the hungry little girls who gave away their breakfasts and contented themselves with bread and milk on Christmas morning.

Mary Hinman Abel, Promoting Nutrition, 1890. This excerpt is from a cookbook that won a prize from the American Public Health Association. The author had studied community cooking projects in Europe and worked to meet the needs of Boston’s poor. How does she propose to feed people on 13 cents a day — her most basic menu? What assumptions does she make about her audience? In what ways was her cookbook, itself, a product of industrialization?

For family of six, average price 78 cents per day, or 13 cents per person.

… I am going to consider myself as talking to the mother of a family who has six mouths to feed, and no more money than this to do it with. Perhaps this woman has never kept accurate accounts. … I have in mind the wife [who has] time to attend to the housework and children. If a woman helps earn, as in a factory, doing most of her housework after she comes home at night, she must certainly have more money than in the first case in order to accomplish the same result.

… The Proteid column is the one that you must look to most carefully because it is furnished at the most expense, and it is very important that it should not fall below the figures I have given [or] your family would be undernourished.

[Sample spring menu]

Breakfast. Milk Toast. Coffee.

Dinner. Stuffed Beef’s Heart. Potatoes stewed with Milk. Dried Apple Pie. Bread and Cheese. Corn Coffee.

Supper. Noodle Soup (from Saturday). Boiled Herring. Bread. Tea.

Proteids. (oz.) 21.20 Fats. (oz.) 14.39 Carbohydrates. (oz.) 77.08 Cost in Cents. 76 Werner Sombart, Why Is There No Socialism in the United States?, 1906. Sombart, a German sociologist, compared living conditions in Germany and the United States in order to answer the question above. What conclusion did he reach?

The American worker eats almost three times as much meat, three times as much flour and four times as much sugar as his German counterpart. … The American worker is much closer to the better sections of the German middle class than to the German wage-labouring class. He does not merely eat, but dines. …

It is no wonder if, in such a situation, any dissatisfaction with the “existing social order” finds difficulty in establishing itself in the mind of the worker. … All Socialist utopias came to nothing on roast beef and apple pie.

Helen Campbell, Prisoners of Poverty, 1887. A journalist, Campbell investigated the conditions of low-paid seamstresses in New York City who did piecework in their apartments. Like Abel (source 3), she tried to teach what she called “survival economics.” Here, a woman responds to Campbell’s suggestion that she cook beans for better nutrition.

“Beans!” said one indignant soul. “What time have I to think of beans, or what money to buy coal to cook ’em? What you’d want if you sat over a machine fourteen hours a day would be tea like lye to put a back-bone in you. That’s why we have tea always in the pot, and it don’t make much odds what’s with it. A slice of bread is about all. … We’d our tea an’ bread an’ a good bit of fried beef or pork, maybe, when my husband was alive an’ at work. … It’s the tea that keeps you up.”

Julian Street, Show and Extravagance, 1910. Street, a journalist, was invited to an elite home in Buffalo, New York, for a dinner that included cocktails, fine wines, caviar, a roast, Turkish coffee, and cigars.

Before we left New York there was newspaper talk about some rich women who had organized a movement of protest against the ever-increasing American tendency toward show and extravagance. … Our hostess [in Buffalo] was the first to mention it, but several other ladies added details. …

”We don’t intend to go to any foolish extremes,” said one. … “We are only going to scale things down and eliminate waste. There is a lot of useless show in this country which only makes it hard for people who can’t afford things. And even for those who can, it is wrong. … Take this little dinner we had tonight. … In future we are all going to give plain little dinners like this.”

“Plain?” I gasped. … “But I didn’t think it had begun yet! I thought this dinner was a kind of farewell feast — that it was —”

Our hostess looked grieved. The other ladies of the league gazed at me reproachfully. … “Didn’t you notice?” asked my hostess. …

“Notice what?”

“That we didn’t have champagne!”

Sources: (2) Louisa May Alcott, Little Women, Part 2, Chapter 2 at xroads.virginia.edu/~HYPER/ALCOTT/ch2.html; (3) Mary Hinman Abel, Practical, Sanitary, and Economic Cooking Adapted to Persons of Moderate and Small Means (American Public Health Association, 1890), 143–154; (4) Werner Sombart, Why Is There No Socialism in the United States?, trans. Patricia M. Hocking and C. T. Husbands (White Plains, NY: International Arts and Sciences Press, 1976), 97, 105–106; (5) Helen Campbell, Prisoners of Poverty (Cambridge, MA: University Press, 1887), 123–124; (6) Julian Street, Abroad at Home (New York: The Century Co., 1915), 37–39.

ANALYZING THE EVIDENCE

Question

These documents were created by journalists and reformers. What audiences did they seek to reach? Why do you think they all focused on food?

Question

Imagine a conversation among these authors. How might we account for the differences in Sombart’s and Campbell’s findings? How might Hine, Abel, and Campbell respond to Alcott’s vision of charitable Christian acts?

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

Question

Using the documents above and your knowledge from this chapter, write a short essay explaining some challenges and opportunities faced by different Americans in the industrializing era — including those of the wealthy elite, the emerging middle class, skilled blue-collar men, and very poorest unskilled laborers. How did labor leaders and reformers seek to persuade prosperous Americans to concern themselves with workers’ problems? To what dominant values did they appeal?