America’s History: Printed Page 589

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 537

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 521

From Domesticity to Women’s Rights

As the United States confronted industrialization, middle-class women steadily expanded their place beyond the household, building reform movements and taking political action. Starting in the 1880s, women’s clubs sprang up and began to study such problems as pollution, unsafe working conditions, and urban poverty. So many formed by 1890 that their leaders created a nationwide umbrella organization, the General Federation of Women’s Clubs. Women justified such work through the ideal of maternalism, appealing to their special role as mothers. Maternalism was an intermediate step between domesticity and modern arguments for women’s equality. “Women’s place is Home,” declared the journalist Rheta Childe Dorr. But she added, “Home is the community. The city full of people is the Family. … Badly do the Home and Family need their mother.”

The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union One maternalist goal was to curb alcohol abuse by prohibiting liquor sales. The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), founded in 1874, spread rapidly after 1879, when charismatic Frances Willard became its leader. More than any other group of the late nineteenth century, the WCTU launched women into reform. Willard knew how to frame political demands in the language of feminine self-sacrifice. “Womanliness first,” she advised her followers; “afterward, what you will.” WCTU members vividly described the plight of abused wives and children when men suffered in the grip of alcoholism. Willard’s motto was “Home Protection,” and though it placed all the blame on alcohol rather than other factors, the WCTU became the first organization to identify and combat domestic violence.

The prohibitionist movement drew activists from many backgrounds. Middle-class city dwellers worried about the link between alcoholism and crime, especially in the growing immigrant wards. Rural citizens equated liquor with big-city sins such as prostitution and political corruption. Methodists, Baptists, Mormons, and members of other denominations condemned drinking for religious reasons. Immigrants passionately disagreed, however: Germans and Irish Catholics enjoyed their Sunday beer and saw no harm in it. Saloons were a centerpiece of working-class leisure and community life, offering free lunches, public toilets, and a place to share neighborhood news. Thus, while some labor unions advocated voluntary temperance, attitudes toward prohibition divided along ethnic, religious, and class lines.

WCTU activism led some leaders to raise radical questions about the shape of industrial society. As she investigated alcohol abuse, Willard increasingly confronted poverty, hunger, unemployment, and other industrial problems. “Do Everything,” she urged her members. Across the United States, WCTU chapters founded soup kitchens and free libraries. They introduced a German educational innovation, the kindergarten. They investigated prison conditions. Though she did not persuade most prohibitionists to follow her lead, Willard declared herself a Christian Socialist and urged more attention to workers’ plight. She advocated laws establishing an eight-hour workday and abolishing child labor.

Willard also called for women’s voting rights, lending powerful support to the independent suffrage movement that had emerged during Reconstruction. Controversially, the WCTU threw its energies behind the Prohibition Party, which exercised considerable clout during the 1880s. Women worked in the party as speakers, convention delegates, and even local candidates. Liquor was big business, and powerful interests mobilized to block antiliquor legislation. In many areas — particularly the cities — prohibition simply did not gain majority support. Willard retired to England, where she died in 1898, worn and discouraged by many defeats. But her legacy was powerful. Other groups took up the cause, eventually winning national prohibition after World War I.

Through its emphasis on human welfare, the WCTU encouraged women to join the national debate over poverty and inequality of wealth. Some became active in the People’s Party of the 1890s, which welcomed women as organizers and stump speakers. Others led groups such as the National Congress of Mothers, founded in 1897, which promoted better child-rearing techniques in rural and working-class families. The WCTU had taught women how to lobby, raise money, and even run for office. Willard wrote that “perhaps the most significant outcome” of the movement was women’s “knowledge of their own power.”

Women, Race, and Patriotism As in temperance work, women played central roles in patriotic movements and African American community activism. Members of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR), founded in 1890, celebrated the memory of Revolutionary War heroes. Equally influential was the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC), founded in 1894 to extol the South’s “Lost Cause.” The UDC’s elite southern members shaped Americans’ memory of the Civil War by constructing monuments, distributing Confederate flags, and promoting school textbooks that defended the Confederacy and condemned Reconstruction. The UDC’s work helped build and maintain support for segregation and disenfranchisement (Chapter 15, Thinking Like a Historian).

African American women did not sit idle in the face of this challenge. In 1896, they created the National Association of Colored Women. Through its local clubs, black women arranged for the care of orphans, founded homes for the elderly, advocated temperance, and undertook public health campaigns. Such women shared with white women a determination to carry domesticity into the public sphere. Journalist Victoria Earle Matthews hailed the American home as “the foundation upon which nationality rests, the pride of the citizen, and the glory of the Republic.” She and other African American women used the language of domesticity and respectability to justify their work.

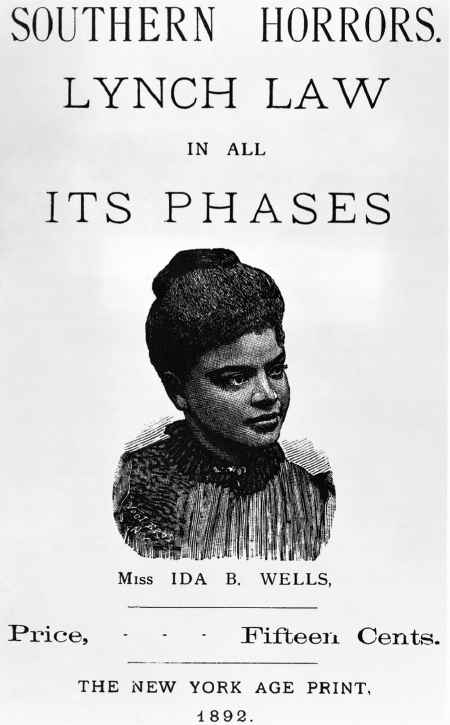

One of the most radical voices was Ida B. Wells, who as a young Tennessee schoolteacher sued the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad for denying her a seat in the ladies’ car. In 1892, a white mob in Memphis invaded a grocery store owned by three of Wells’s friends, angry that it competed with a nearby white-owned store. When the black store owners defended themselves, wounding several of their attackers, all three were lynched. Grieving their deaths, Wells left Memphis and urged other African Americans to join her in boycotting the city’s white businesses. As a journalist, she launched a one-woman campaign against lynching. Wells’s investigations demolished the myth that lynchers were reacting to the crime of interracial rape; she showed that the real cause was more often economic competition, a labor dispute, or a consensual relationship between a white woman and a black man. Settling in Chicago, Wells became a noted and accomplished reformer, but in an era of increasing racial injustice, few whites supported her cause.

The largest African American women’s organization arose within the National Baptist Church (NBC), which by 1906 represented 2.4 million black churchgoers. Founded in 1900, the Women’s Convention of the NBC funded night schools, health clinics, kindergartens, day care centers, and prison outreach programs. Adella Hunt Logan, born in Alabama, exemplified how such work could lead women to demand political rights. Educated at Atlanta University, Logan became a women’s club leader, teacher, and suffrage advocate. “If white American women, with all their mutual and acquired advantage, need the ballot,” she declared, “how much more do Black Americans, male and female, need the strong defense of a vote to help secure them their right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness?”

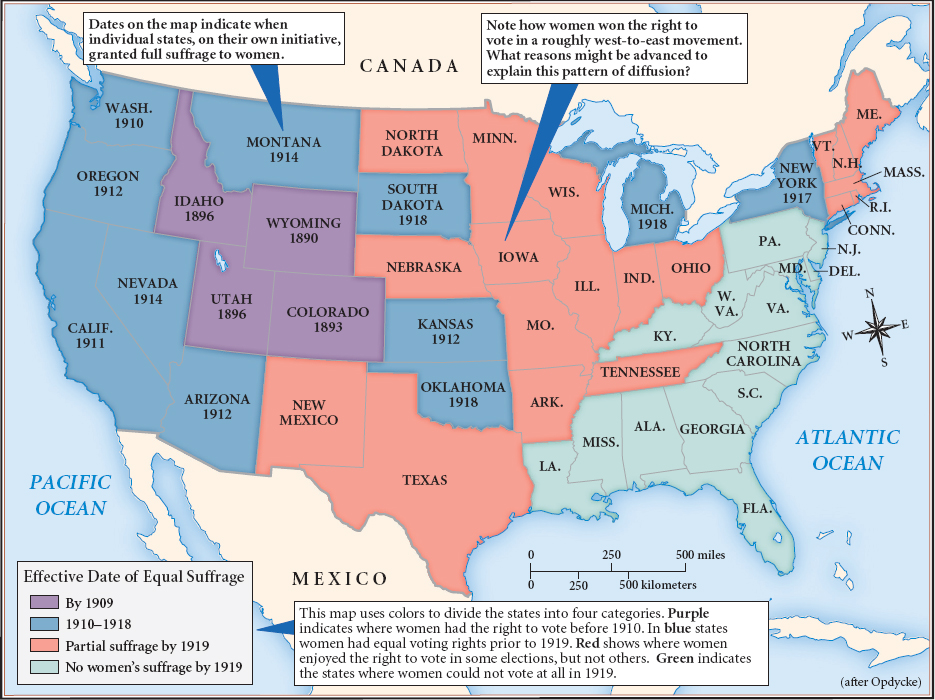

Women’s Rights Though it had split into two rival organizations during Reconstruction, the movement for women’s suffrage reunited in 1890 in the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Soon afterward, suffragists built on earlier victories in the West, winning full ballots for women in Colorado (1893), Idaho (1896), and Utah (1896, reestablished as Utah gained statehood). Afterward, movement leaders were discouraged by a decade of state-level defeats and Congress’s refusal to consider a constitutional amendment. But suffrage again picked up momentum after 1911 (Map 18.2). By 1913, most women living west of the Mississippi River had the ballot. In other localities, women could vote in municipal elections, school elections, or liquor referenda.

The rising prominence of the women’s suffrage movement had an ironic result: it prompted some women — and men — to organize against it, in groups such as the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage (1911). Antisuffragists argued that it was expensive to add so many voters to the rolls; wives’ ballots would just “double their husbands’ votes” or worse, cancel them out, subjecting men to “petticoat rule.” Some antisuffragists also argued that voting would undermine women’s special roles as disinterested reformers: no longer above the fray, they would be plunged into the “cesspool of politics.” In short, women were “better citizens without the ballot.” Such arguments helped delay passage of national women’s suffrage until after World War I.

By the 1910s, some women moved beyond suffrage to take a public stance for what they called feminism — women’s full political, economic, and social equality. A famous site of sexual rebellion was New York’s Greenwich Village, where radical intellectuals, including many gays and lesbians, created a vibrant community. Among other political activities, women there founded the Heterodoxy Club (1912), open to any woman who pledged not to be “orthodox in her opinions.” The club brought together intellectuals, journalists, and labor organizers. Almost all supported suffrage, but they had a more ambitious view of what was needed for women’s liberation. “I wanted to belong to the human race, not to a ladies’ aid society,” wrote one divorced journalist who joined Heterodoxy. Feminists argued that women should not simply fulfill expectations of feminine self-sacrifice; they should work on their own behalf.

UNDERSTAND POINTS OF VIEW

Question

How did women use widespread beliefs about their “special role” to justify political activism, and for what goals?