America’s History: Printed Page 660

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 603

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 584

Economic Reforms

In an era of rising corporate power, many Democrats believed workers needed stronger government to intervene on their behalf, and they began to transform themselves into a modern, state-building party. The Wilson administration achieved a series of landmark measures — at least as significant as those enacted during earlier administrations, and perhaps more so (Table 20.1). The most enduring was the federal progressive income tax. “Progressive,” by this definition, referred to the fact that it was not a flat tax but rose progressively toward the top of the income scale. The tax, passed in the 1890s but rejected by the Supreme Court, was reenacted as the Sixteenth Amendment to the Constitution, ratified by the states in February 1913. The next year, Congress used the new power to enact an income tax of 1 to 7 percent on Americans with annual incomes of $4,000 or more. At a time when white male wageworkers might expect to make $800 per year, the tax affected less than 5 percent of households.

| Major Federal Progressive Measures, 1883–1921 |

| Before 1900 |

| Pendleton Civil Service Act (1883) |

| Hatch Act (1887; Chapter 17) |

| Interstate Commerce Act (1887; Chapter 17) |

| Sherman Antitrust Act (1890) |

| Federal income tax (1894; struck down by Supreme Court, 1895) |

| During Theodore Roosevelt’s Presidency, 1901–1909 |

| Newlands Reclamation Act for federal irrigation (1902) |

| Elkins Act (1903) |

| First National Wildlife Refuge (1903; Chapter 18) |

| Bureau of Corporations created to aid Justice Department antitrust work (1903) |

| National Forest Service created (1905) |

| Antiquities Act (1906; Chapter 18) |

| Pure Food and Drug Act (1906; Chapter 19) |

| Hepburn Act (1906) |

| First White House Conference on Dependent Children (1909) |

| During William Howard Taft’s Presidency, 1909–1913 |

| Mann Act preventing interstate prostitution (1910; Chapter 19) |

| Children’s Bureau created in the U.S. Labor Department (1912) |

| U.S. Commission on Industrial Relations appointed (1912) |

| During Woodrow Wilson’s Presidency, 1913–1920 |

| Sixteenth Amendment to the Constitution; federal income tax (1913) |

| Seventeenth Amendment to the Constitution; direct election of U.S. senators (1913) |

| Federal Reserve Act (1913) |

| Clayton Antitrust Act (1914) |

| Seamen’s Act (1915) |

| Workmen’s Compensation Act (1916) |

| Adamson Eight-Hour Act (1916) |

| National Park Service created (1916; Chapter 18) |

| Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution; prohibition of liquor (1919; Chapter 22) |

| Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution; women’s suffrage (1920; Chapter 21) |

Three years later, Congress followed this with an inheritance tax. These measures created an entirely new way to fund the federal government, replacing Republicans’ high tariff as the chief source of revenue. Over subsequent decades, especially between the 1930s and the 1970s, the income tax system markedly reduced America’s extremes of wealth and poverty.

Wilson also reorganized the financial system to address the absence of a central bank. At the time, the main function of national central banks was to back up commercial banks in case they could not meet their obligations. In the United States, the great private banks of New York (such as J. P. Morgan’s) assumed this role; if they weakened, the entire system could collapse. This had nearly happened in 1907, when the Knickerbocker Trust Company failed, precipitating a panic. The Federal Reserve Act (1913) gave the nation a banking system more resistant to such crises. It created twelve district reserve banks funded and controlled by their member banks, with a central Federal Reserve Board to impose regulation. The Federal Reserve could issue currency — paper money based on assets held in the system — and set the interest rate that district reserve banks charged to their members. It thereby regulated the flow of credit to the general public. The act strengthened the banking system and, to a modest degree, discouraged risky speculation on Wall Street.

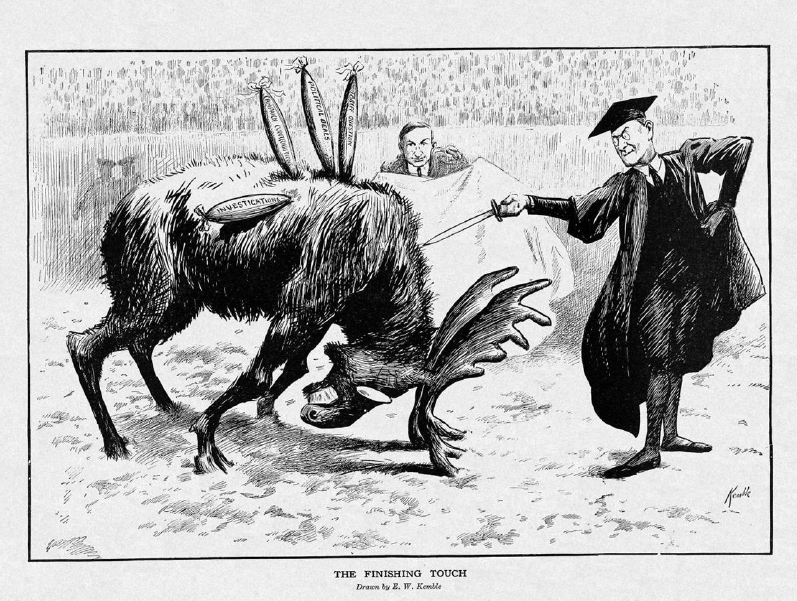

Wilson and the Democratic Congress turned next to the trusts. In doing so, Wilson relied heavily on Louis D. Brandeis, the celebrated people’s lawyer. Brandeis denied that monopolies were efficient. On the contrary, he believed the best source of efficiency was vigorous competition in a free market. The trick was to prevent trusts from unfairly using their power to curb such competition. In the Clayton Antitrust Act (1914), which amended the Sherman Act, the definition of illegal practices was left flexible, subject to the test of whether an action “substantially lessen[ed] competition.” The new Federal Trade Commission received broad powers to decide what was fair, investigating companies and issuing “cease and desist” orders against anticompetitive practices.

Labor issues, meanwhile, received attention from a blue-ribbon U.S. Commission on Industrial Relations, appointed near the end of Taft’s presidency and charged with investigating the conditions of labor. In its 1913 report, the commission summed up the impact of industrialization on low-skilled workers. Many earned $10 or less a week and endured regular episodes of unemployment; some faced long-term poverty and hardship. Workers held “an almost universal conviction” that they were “denied justice.” The commission concluded that a major cause of industrial violence was the ruthless antiunionism of American employers. In its key recommendation, the report called for federal laws protecting workers’ right to organize and engage in collective bargaining. Though such laws were, in 1915, too radical to win passage, the commission helped set a new national agenda that would come to fruition in the 1930s.

Guided by the commission’s revelations, President Wilson warmed up to labor. In 1915 and 1916, he championed a host of bills to benefit American workers. They included the Adamson Act, which established an eight-hour day for railroad workers; the Seamen’s Act, which eliminated age-old abuses of merchant sailors; and a workmen’s compensation law for federal employees. Wilson, despite initial modest goals, presided over a major expansion of federal authority, perhaps the most significant since Reconstruction. The continued growth of U.S. government offices during Wilson’s term reflected a reality that transcended party lines: corporations had grown in size and power, and Americans increasingly wanted federal authority to grow, too.

Wilson’s reforms did not extend to the African Americans who had supported him in 1912. In fact, the president rolled back certain Republican policies, such as selected appointments of black postmasters. “I tried to help elect Wilson,” W. E. B. Du Bois reflected gloomily, but “under Wilson came the worst attempt at Jim Crow legislation and discrimination in civil service that we had experienced since the Civil War.” Wilson famously praised the film Birth of a Nation (1915), which depicted the Reconstruction-era Ku Klux Klan in heroic terms. In this way, Democratic control of the White House helped set the tone for the Klan’s return in the 1920s.

TRACE CHANGE OVER TIME

Question

To what degree did reforms of the Wilson era fulfill goals that various agrarian-labor advocates and progressives had sought?