America’s History: Printed Page 686

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 626

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 608

“Over There”

To Americans, Europe seemed a great distance away. Many assumed the United States would simply provide munitions and economic aid. “Good Lord,” exclaimed one U.S. senator to a Wilson administration official, “you’re not going to send soldiers over there, are you?” But when General John J. Pershing asked how the United States could best support the Allies, the French commander put it bluntly: “Men, men, and more men.” Amid war fever, thousands of young men prepared to go “over there,” in the words of George M. Cohan’s popular song: “Make your Daddy glad to have had such a lad. / Tell your sweetheart not to pine, / To be proud her boy’s in line.”

Americans Join the War In 1917, the U.S. Army numbered fewer than 200,000 soldiers; needing more men, Congress instituted a military draft in May 1917. In contrast to the Civil War, when resistance was common, conscription went smoothly, partly because local, civilian-run draft boards played a central role in the new system. Still, draft registration demonstrated government’s increasing power over ordinary citizens. On a single day — June 5, 1917 — more than 9.5 million men between the ages of twenty-one and thirty registered at local voting precincts for possible military service.

President Wilson chose General Pershing to head the American Expeditionary Force (AEF), which had to be trained, outfitted, and carried across the submarine-plagued Atlantic. This required safer shipping. When the United States entered the war, German U-boats were sinking 900,000 tons of Allied ships each month. By sending merchant and troop ships in armed convoys, the U.S. Navy cut that monthly rate to 400,000 tons by the end of 1917. With trench warfare grinding on, Allied commanders pleaded for American soldiers to fill their depleted units, but Pershing waited until the AEF reached full strength. As late as May 1918, the brunt of the fighting fell to the French and British.

The Allies’ burden increased when the Eastern Front collapsed following the Bolshevik (Communist) Revolution in Russia in November 1917. To consolidate power at home, the new Bolshevik government, led by Vladimir Lenin, sought peace with the Central Powers. In a 1918 treaty, Russia surrendered its claims over vast parts of its territories in exchange for peace. Released from war against Germany, the Bolsheviks turned their attention to a civil war at home. Terrified by communism, Japan and several Allied countries, including the United States, later sent troops to fight the Bolsheviks and aid forces loyal to the deposed tsar. But after a four-year civil war, Lenin’s forces established full control over Russia and reclaimed Ukraine and other former possessions.

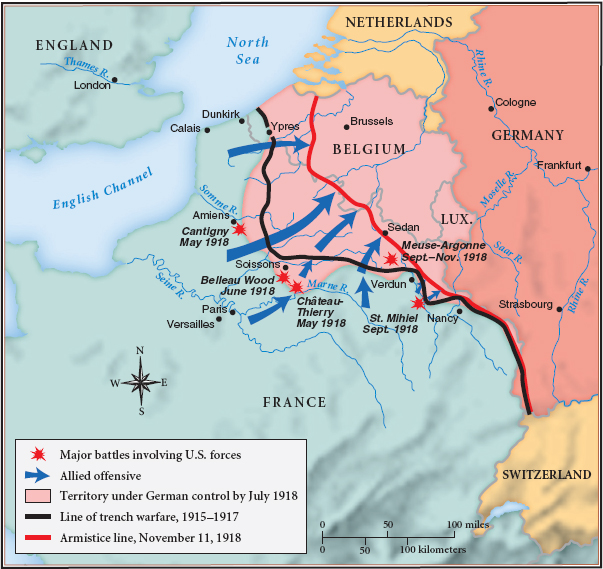

Peace with Russia freed Germany to launch a major offensive on the Western Front. By May 1918, German troops had advanced to within 50 miles of Paris. Pershing at last committed about 60,000 U.S. soldiers to support the French defense. With American soldiers engaged in massive numbers, Allied forces brought the Germans to a halt in July; by September, they forced a retreat. Pershing then pitted more than one million American soldiers against an outnumbered and exhausted German army in the Argonne forest. By early November, this attack broke German defenses at a crucial rail hub, Sedan. The cost was high: 26,000 Americans killed and 95,000 wounded (Map 21.3). But the flood of U.S. troops and supplies determined the outcome. Recognizing inevitable defeat and facing popular uprisings at home, Germany signed an armistice on November 11, 1918. The Great War was over.

The American Fighting Force By the end of World War I, almost 4 million American men — popularly known as “doughboys” — wore U.S. uniforms, as did several thousand female nurses. The recruits reflected America’s heterogeneity: one-fifth had been born outside the United States, and soldiers spoke forty-nine different languages. Though ethnic diversity worried some observers, most predicted that military service would promote Americanization.

Over 400,000 African American men enlisted, accounting for 13 percent of the armed forces. Their wartime experiences were often grim: serving in segregated units, they were given the most menial tasks. Racial discrimination hampered military efficiency and provoked violence at several camps. The worst incident occurred in August 1917, when, after suffering a string of racial attacks, black members of the 24th Infantry’s Third Battalion rioted in Houston, killing 15 white civilians and police officers. The army tried 118 of the soldiers in military courts for mutiny and riot, hanged 19, and sentenced 63 to life in prison.

Unlike African Americans, American Indians served in integrated combat units. Racial stereotypes about Native Americans’ prowess as warriors enhanced their military reputations, but it also prompted officers to assign them hazardous duties as scouts and snipers. About 13,000, or 25 percent, of the adult male American Indian population served during the war; roughly 5 percent died, compared to 2 percent for the military as a whole.

Most American soldiers escaped the horrors of sustained trench warfare. Still, during the brief period of U.S. participation, over 50,000 servicemen died in action; another 63,000 died from disease, mainly the devastating influenza pandemic that began early in 1918 and, over the next two years, killed 50 million people worldwide. The nation’s military deaths, though substantial, were only a tenth as many as the 500,000 American civilians who died of this terrible epidemic — not to mention the staggering losses of Europeans in the war (America Compared).

EXPLAIN CONSEQUENCES

Question

How did U.S. military entry into World War I affect the course of the war?