America’s History: Printed Page 783

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 711

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 690

Migration and the Wartime City

The war determined where people lived. When men entered the armed services, their families often followed them to training bases or points of debarkation. Civilians moved to take high-paying defense jobs. About 15 million Americans changed residences during the war years, half of them moving to another state. One of them was Peggy Terry, who grew up in Paducah, Kentucky; worked in a shell-loading plant in nearby Viola; and then moved to a defense plant in Michigan. There, she recalled, “I met all those wonderful Polacks [Polish Americans]. They were the first people I’d ever known that were any different from me. A whole new world just opened up.”

As the center of defense production for the Pacific war, California experienced the largest share of wartime migration. The state welcomed nearly three million new residents and grew by 53 percent during the war. “The Second Gold Rush Hits the West,” announced the San Francisco Chronicle in 1943. One-tenth of all federal dollars flowed into California, and the state’s factories turned out one-sixth of all war materials. People went where the defense jobs were: to Los Angeles, San Diego, and cities around San Francisco Bay. Some towns grew practically overnight; within two years of the opening of the Kaiser Corporation shipyard in Richmond, California, the town’s population had quadrupled. Other industrial states — notably New York, Illinois, Michigan, and Ohio — also attracted both federal dollars and migrants on a large scale.

The growth of war industries accelerated patterns of rural-urban migration. Cities grew dramatically, as factories, shipyards, and other defense work drew millions of citizens from small towns and rural areas. This new mobility, coupled with people’s distance from their hometowns, loosened the authority of traditional institutions and made wartime cities vibrant and exciting. Around-the-clock work shifts kept people on the streets night and day, and bars, jazz clubs, dance halls, and movie theaters proliferated, fed by the ready cash of war workers.

Racial Conflict Migration and more fluid social boundaries meant that people of different races and ethnicities mixed in the booming cities. Over one million African Americans left the rural South for California, Illinois, Michigan, Ohio, and Pennsylvania — a continuation of the Great Migration earlier in the century. As blacks and whites competed for jobs and housing, racial conflicts broke out in more than a hundred cities in 1943. Detroit saw the worst violence. In June 1943, a riot incited by southern-born whites and Polish Americans against African Americans left thirty-four people dead and hundreds injured.

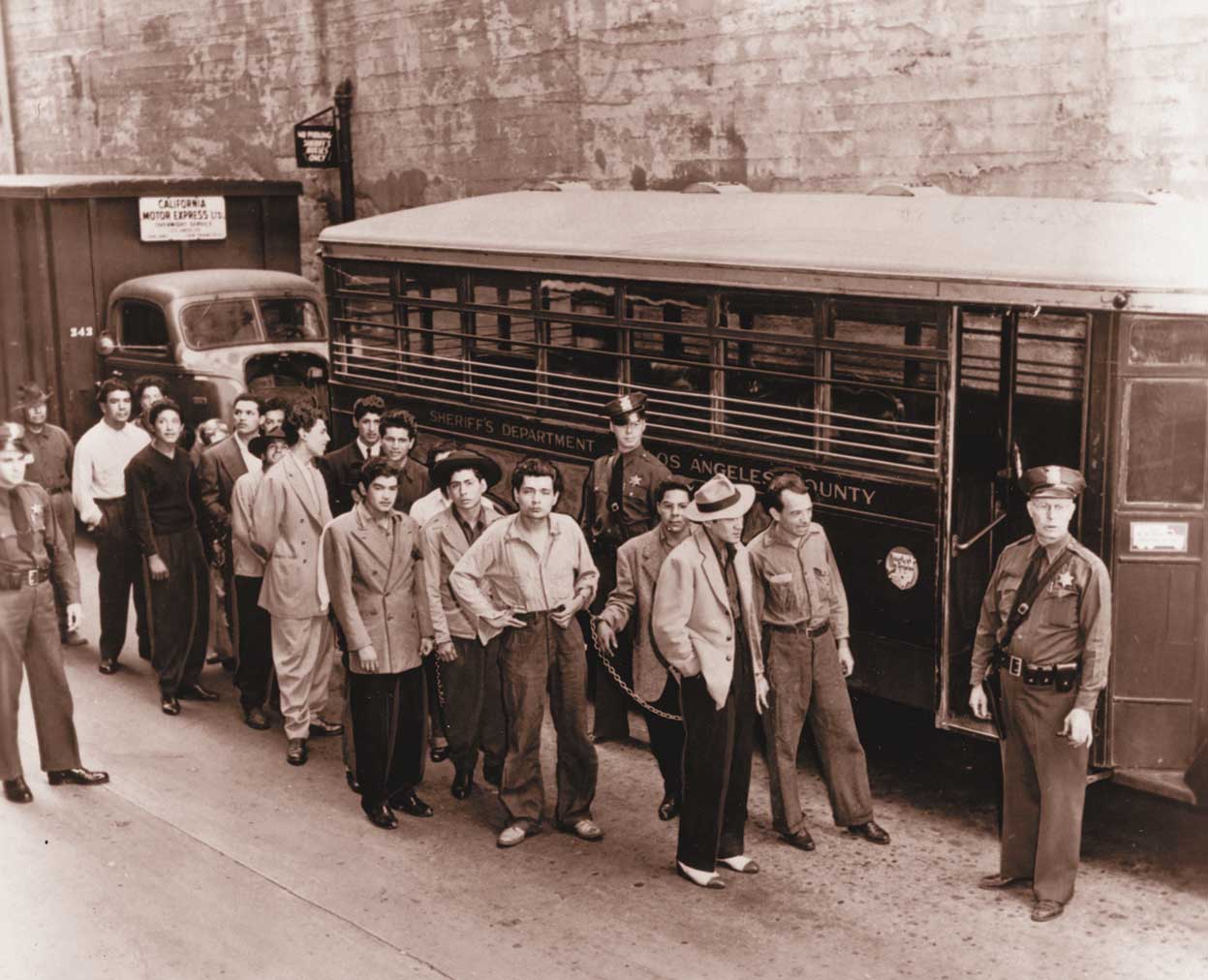

Racial conflict struck the West as well. In Los Angeles, male Hispanic teenagers formed pachuco (youth) gangs. Many dressed in “zoot suits” — broad-brimmed felt hats, thigh-length jackets with wide lapels and padded shoulders, pegged trousers, and clunky shoes. Pachucas (young women) favored long coats, huarache sandals, and pompadour hairdos. Other working-class teenagers in Los Angeles and elsewhere took up the zoot-suit style to underline their rejection of middle-class values. To many adults, the zoot suit symbolized juvenile delinquency. Rumors circulating in Los Angeles in June 1943 that a pachuco gang had beaten an Anglo (white) sailor set off a four-day riot in which hundreds of Anglo servicemen roamed through Mexican American neighborhoods and attacked zoot-suiters, taking special pleasure in slashing their pegged pants. In a stinging display of bias, Los Angeles police officers arrested only Mexican American youth, and the City Council passed an ordinance outlawing the wearing of the zoot suit.

Gay and Lesbian Communities Wartime migration to urban centers created new opportunities for gay men and women to establish communities. Religious morality and social conventions against gays and lesbians kept the majority of them silent and their sexuality hidden. During the war, however, cities such as New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Chicago, and even Kansas City, Buffalo, and Dallas developed vibrant gay neighborhoods, sustained in part by a sudden influx of migrants and the relatively open wartime atmosphere. These communities became centers of the gay rights movement of the 1960s and 1970s (see “The Women’s Movement and Gay Rights” in Chapter 29).

The military tried to screen out homosexuals but had limited success. Once in the services, homosexuals found opportunities to participate in a gay culture often more extensive than that in civilian life. In the last twenty years, historians have documented thriving communities of gay and lesbian soldiers in the World War II military. Some “came out under fire,” as one historian put it, but most kept their sexuality hidden from authorities, because army officers, doctors, and psychiatrists treated homosexuality as a psychological disorder that was grounds for dishonorable discharge.

EXPLAIN CONSEQUENCES

Question

What effects did wartime migration have on the United States?