America’s History: Printed Page 813

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 739

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 719

Containment in Asia

As with Germany, American officials believed that restoring Japan’s economy, while limiting its military influence, would ensure prosperity and contain communism in East Asia. After dismantling Japan’s military, American occupation forces under General Douglas MacArthur drafted a democratic constitution and paved the way for the restoration of Japanese sovereignty in 1951. Considering the scorched-earth war that had just ended, this was a remarkable achievement, thanks partly to the imperious MacArthur but mainly to the Japanese, who embraced peace and accepted U.S. military protection. However, events on the mainland of Asia proved much more difficult for the United States to shape to its advantage.

Civil War in China A civil war had been raging in China since the 1930s as Communist forces led by Mao Zedong (Mao Tse-tung) fought Nationalist forces under Jiang Jieshi (Chiang Kai-shek). Fearing a Communist victory, between 1945 and 1949 the United States provided $2 billion to Jiang’s army. Pressing Truman to “save” China, conservative Republican Ohio senator Robert A. Taft predicted that “the Far East is ultimately even more important to our future peace than is Europe.” By 1949, Mao’s forces held the advantage. Truman reasoned that to save Jiang, the United States would have to intervene militarily. Unwilling to do so, he cut off aid and left the Nationalists to their fate. The People’s Republic of China was formally established under Mao on October 1, 1949, and the remnants of Jiang’s forces fled to Taiwan.

Both Stalin and Truman expected Mao to take an independent line, as the Communist leader Tito had just done in Yugoslavia. Mao, however, aligned himself with the Soviet Union, partly out of fear that the United States would rearm the Nationalists and invade the mainland. As attitudes hardened, many Americans viewed Mao’s success as a defeat for the United States. The pro-Nationalist “China lobby” accused Truman’s State Department of being responsible for the “loss” of China. Sensitive to these charges, the Truman administration refused to recognize “Red China” and blocked China’s admission to the United Nations. But the United States pointedly declined to guarantee Taiwan’s independence, and in fact accepted the outcome on the mainland. (Since 1982, however, the United States has recognized Taiwanese sovereignty.)

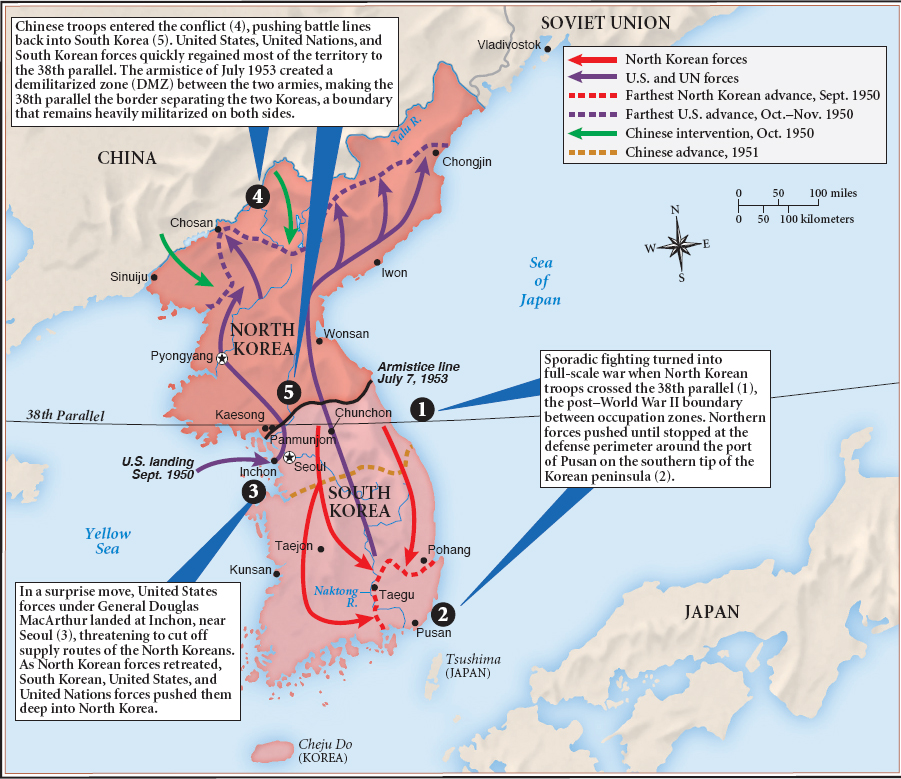

The Korean War The United States took a stronger stance in Korea. The United States and the Soviet Union had agreed at the close of World War II to occupy the Korean peninsula jointly, temporarily dividing the former Japanese colony at the 38th parallel. As tensions rose in Europe, the 38th parallel hardened into a permanent demarcation line. The Soviets supported a Communist government, led by Kim Il Sung, in North Korea; the United States backed a right-wing Nationalist, Syngman Rhee, in South Korea. The two sides had waged low-level war since 1945, and both leaders were spoiling for a more definitive fight. However, neither Kim nor Rhee could launch an all-out offensive without the backing of his sponsor. Washington repeatedly said no, and so did Moscow. But Kim continued to press Stalin to permit him to reunify the nation. Convinced by the North Koreans that victory would be swift, the Soviet leader finally relented in the late spring of 1950.

On June 25, 1950, the North Koreans launched a surprise attack across the 38th parallel (Map 25.2). Truman immediately asked the UN Security Council to authorize a “police action” against the invaders. The Soviet Union was boycotting the Security Council to protest China’s exclusion from the United Nations and could not veto Truman’s request. With the Security Council’s approval of a “peacekeeping force,” Truman ordered U.S. troops to Korea. The rapidly assembled UN army in Korea was overwhelmingly American, with General Douglas MacArthur in command. At first, the North Koreans held a distinct advantage, but MacArthur’s surprise amphibious attack at Inchon gave the UN forces control of Seoul, the South Korean capital, and almost all the territory up to the 38th parallel.

The impetuous MacArthur then ordered his troops across the 38th parallel and led them all the way to the Chinese border at the Yalu River. It was a major blunder, certain to draw China into the war. Sure enough, a massive Chinese counterattack forced MacArthur’s forces into headlong retreat back down the Korean peninsula. Then stalemate set in. With weak public support for the war in the United States, Truman and his advisors decided to work for a negotiated peace. MacArthur disagreed and denounced the Korean stalemate, declaring, “There is no substitute for victory.” On April 11, 1951, Truman relieved MacArthur of his command. Truman’s decision was highly unpopular, especially among conservative Republicans, but he had likely saved the nation from years of costly warfare with China.

Notwithstanding MacArthur’s dismissal, the war dragged on for more than two years. An armistice in July 1953, pushed by the newly elected president, Dwight D. Eisenhower, left Korea divided at the original demarcation line. North Korea remained firmly allied with the Soviet Union; South Korea signed a mutual defense treaty with the United States. It had been the first major proxy battle of the Cold War, in which the Soviet Union and United States took sides in a civil conflict. It would not be the last.

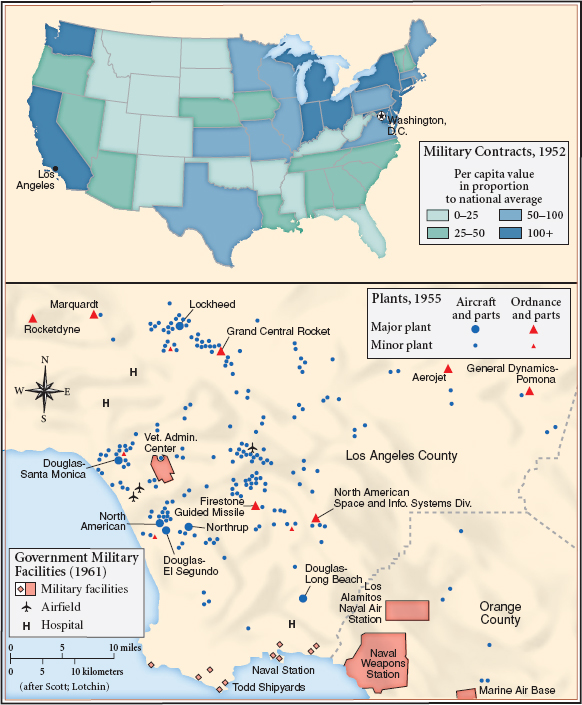

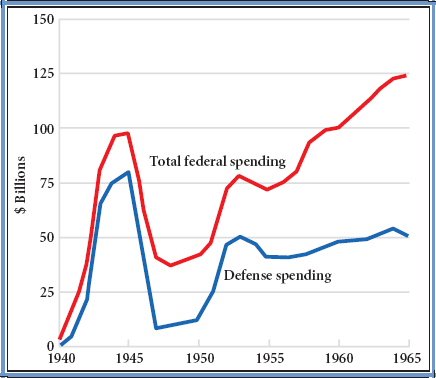

The Korean War had far-reaching consequences. Truman’s decision to commit troops without congressional approval set a precedent for future undeclared wars. His refusal to unleash atomic bombs, even when American forces were reeling under a massive Chinese attack, set ground rules for Cold War conflict. The war also expanded American involvement in Asia, transforming containment into a truly global policy — and significantly boosting Japan’s struggling postwar economy. Finally, the Korean War ended Truman’s resistance to a major military buildup. Defense expenditures grew from $13 billion in 1950, roughly one-third of the federal budget, to $50 billion in 1953, nearly two-thirds of the budget (Map 25.3). American foreign policy had become more global, more militarized, and more expensive (Figure 25.1). Even in times of peace, the United States now functioned in a state of permanent military mobilization.

The Munich Analogy Behind much of U.S. foreign policy in the first two decades of the Cold War lay the memory of appeasement (see “The Failure of Appeasement” in Chapter 24). The generation of politicians and officials who designed the containment strategy had come of age in the shadow of Munich, the conference in 1938 at which the Western democracies had appeased Hitler by offering him part of Czechoslovakia, paving the road to World War II. Applying the lessons of Munich, American presidents believed that “appeasing” Stalin (and subsequent Soviet rulers Nikita Khrushchev and Leonid Brezhnev) would have the same result: wider war. Thus in Germany, Greece, and Korea, and later in Iran, Guatemala, and Vietnam, the United States staunchly resisted the Soviets — or what it perceived as Soviet influence. The Munich analogy strengthened the U.S. position in a number of strategic conflicts, particularly over the fate of Germany. But it also drew Americans into armed conflicts — and convinced them to support repressive, right-wing regimes — that compromised, as much as supported, stated American principles.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

Question

How did U.S. containment strategy in Asia compare to containment in Europe?