America’s History: Printed Page 820

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 745

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 725

Red Scare: The Hunt for Communists

Cold War liberalism was premised on the grave domestic threat posed, many believed, by Communists and Communist sympathizers. Was there any significant Soviet penetration of the American government? Records opened after the 1991 disintegration of the Soviet Union indicate that there was, although it was largely confined to the 1930s. Among American suppliers of information to Moscow were FDR’s assistant secretary of the treasury, Harry Dexter White; FDR’s administrative aide Laughlin Currie; a strategically placed midlevel group in the State Department; and several hundred more, some identified only by code name, working in a range of government departments and agencies.

How are we to explain this? Many of these enlistees in the Soviet cause had been bright young New Dealers in the mid-1930s, when the Soviet-backed Popular Front suggested that the lines separating liberalism, progressivism, and communism were permeable (see “The Popular Front” in Chapter 24). At that time, the United States was not at war and never expected to be. And when war did come, the Soviet Union was an American ally. For critics of the informants, however, there remained the time between the Nazi-Soviet Pact and the German invasion of the Soviet Union, a nearly two-year period during which cooperation with the Soviet Union could be seen in a less positive light. Moreover, passing secrets to another country, even a wartime ally, was simply indefensible to many Americans. The lines between U.S. and Soviet interests blurred for some; for others, they remained clear and definite.

After World War II, however, most suppliers of information to the Soviets apparently ceased spying. For one thing, the professional apparatus of Soviet spying in the United States was dismantled or disrupted by American counterintelligence work. For another, most of the well-connected amateur spies moved on to other careers. Historians have thus developed a healthy skepticism that there was much Soviet espionage in the United States after 1947, but this was not how many Americans saw it at the time. Legitimate suspicions and real fears, along with political opportunism, combined to fuel the national Red Scare, which was longer and more far-reaching than the one that followed World War I (see “The Red Scare” in Chapter 22).

Loyalty-Security Program To insulate his administration against charges of Communist infiltration, Truman issued Executive Order 9835 on March 21, 1947, which created the Loyalty-Security Program. The order permitted officials to investigate any employee of the federal government (some 2.5 million people) for “subversive” activities. Representing a profound centralization of power, the order sent shock waves through every federal agency. Truman intended the order to apply principally to actions designed to harm the United States (sabotage, treason, etc.), but it was broad enough to allow anyone to be accused of subversion for the slightest reason — for marching in a Communistled demonstration in the 1930s, for instance, or signing a petition calling for public housing. Along with suspected political subversives, more than a thousand gay men and lesbians were dismissed from federal employment in the 1950s, victims of an obsessive search for anyone deemed “unfit” for government work.

Following Truman’s lead, many state and local governments, universities, political organizations, churches, and businesses undertook their own antisubversion campaigns, which often included loyalty oaths. In the labor movement, charges of Communist domination led to the expulsion of a number of unions by the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) in 1949. Civil rights organizations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the National Urban League also expelled Communists and “fellow travelers,” or Communist sympathizers. Thus the Red Scare spread from the federal government to the farthest reaches of American organizational, economic, and cultural life.

HUAC The Truman administration had legitimized the vague and malleable concept of “disloyalty.” Others proved willing to stretch the concept even further, beginning with the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), which Congressman Martin Dies of Texas and other conservatives had launched in 1938. After the war, HUAC helped spark the Red Scare by holding widely publicized hearings in 1947 on alleged Communist infiltration in the movie industry. A group of writers and directors dubbed the Hollywood Ten went to jail for contempt of Congress after they refused to testify about their past associations. Hundreds of other actors, directors, and writers whose names had been mentioned in the HUAC investigation were unable to get work, victims of an unacknowledged but very real blacklist honored by industry executives.

Other HUAC investigations had greater legitimacy. One that intensified the anticommunist crusade in 1948 involved Alger Hiss, a former New Dealer and State Department official who had accompanied Franklin Roosevelt to Yalta. A former Communist, Whitaker Chambers, claimed that Hiss was a member of a secret Communist cell operating in the government and had passed him classified documents in the 1930s. Hiss denied the allegations, but California Republican congressman Richard Nixon doggedly pursued the case against him. In early 1950, Hiss was found guilty not of spying but of lying to Congress about his Communist affiliations and was sentenced to five years in federal prison. Many Americans doubted at the time that Hiss was a spy. But the Venona transcripts in the 1990s corroborated a great deal of Chambers’s testimony, and though no definitive proof has emerged, many historians now recognize the strong circumstantial evidence against Hiss.

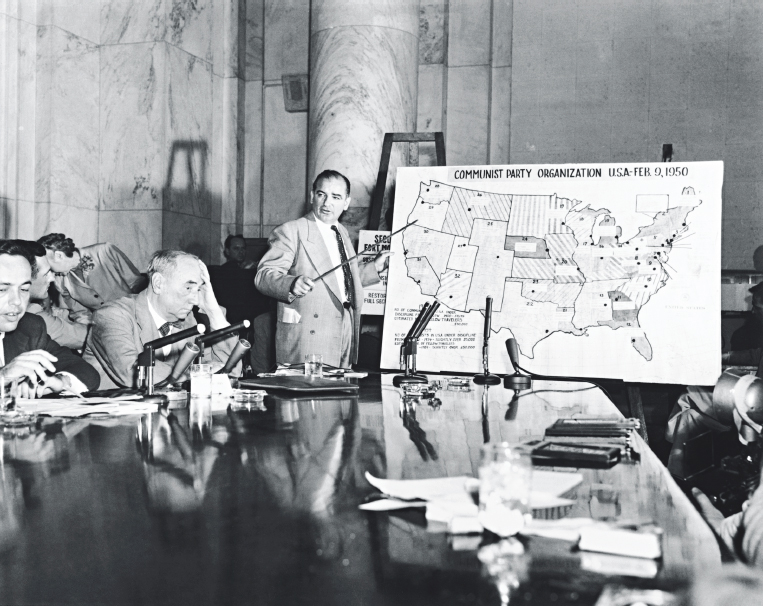

McCarthyism The meteoric career of Senator Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin marked first the apex and then the finale of the Red Scare. In February 1950, McCarthy delivered a bombshell during a speech in Wheeling, West Virginia: “I have here in my hand a list of 205 … a list of names that were made known to the Secretary of State as being members of the Communist Party and who nevertheless are still working and shaping policy in the State Department.” McCarthy later reduced his numbers, gave different figures in different speeches, and never released any names or proof. But he had gained the attention he sought (American Voices).

For the next four years, from his position as chair of the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, McCarthy waged a virulent smear campaign. Critics who disagreed with him exposed themselves to charges of being “soft” on communism. Truman called McCarthy’s charges “slander, lies, [and] character assassination” but could do nothing to curb him. Republicans, for their part, refrained from publicly challenging their most outspoken senator and, on the whole, were content to reap the political benefits. McCarthy’s charges almost always targeted Democrats.

Despite McCarthy’s failure to identify a single Communist in government, several national developments gave his charges credibility with the public. The dramatic 1951 espionage trial of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, followed around the world, fueled McCarthy’s allegations. Convicted of passing atomic secrets to the Soviet Union, the Rosenbergs were executed in 1953. As in the Hiss case, documents released decades later provided some evidence of Julius Rosenberg’s guilt, though not Ethel’s. Their execution nevertheless remains controversial — in part because some felt that anti-Semitism played a role in their sentencing. Also fueling McCarthy’s charges were a series of trials of American Communists between 1949 and 1955 for violation of the 1940 Smith Act, which prohibited Americans from advocating the violent overthrow of the government. Though civil libertarians and two Supreme Court justices vigorously objected, dozens of Communist Party members were convicted. McCarthy was not involved in either the Rosenberg trial or the Smith Act convictions, but these sensational events gave his wild charges some credence.

In early 1954, McCarthy overreached by launching an investigation into subversive activities in the U.S. Army. When lengthy hearings — the first of their kind broadcast on the new medium of television — brought McCarthy’s tactics into the nation’s living rooms, support for him plummeted. In December 1954, the Senate voted 67 to 22 to censure McCarthy for unbecoming conduct. He died from an alcohol-related illness three years later at the age of forty-eight, his name forever attached to a period of political repression of which he was only the most flagrant manifestation.

IDENTIFY CAUSES

Question

What factors led to the postwar Red Scare, and what were its ramifications for civil liberties in the United States?