America’s History: Printed Page 875

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 795

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 776

Mexican Americans and Japanese Americans

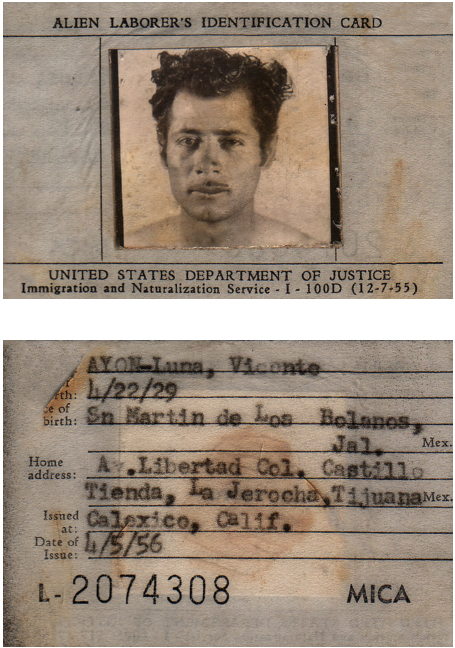

African Americans were the most prominent, but not the only, group in American society to organize against racial injustice in the 1940s. In the Southwest, from Texas to California, Mexican immigrants and Mexican Americans endured a “caste” system not unlike the Jim Crow system in the South. In Texas, for instance, poll taxes kept most Mexican American citizens from voting. Decades of discrimination by employers in agriculture and manufacturing — made possible by the constant supply of cheap labor from across the border — suppressed wages and kept the majority of Mexican Americans barely above poverty. Many lived in colonias or barrios, neighborhoods separated from Anglos and often lacking sidewalks, reliable electricity and water, and public services.

Developments within the Mexican American community set the stage for fresh challenges to these conditions in the 1940s. Labor activism in the 1930s and 1940s, especially in Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) unions with large numbers of Mexican Americans, improved wages and working conditions in some industries and produced a new generation of leaders. More than 400,000 Mexican Americans also served in World War II. Having fought for their country, many returned to the United States determined to challenge their second-class citizenship. Additionally, a new Mexican American middle class began to take shape in major cities such as Los Angeles, San Antonio, El Paso, and Chicago, which, like the African American middle class, gave leaders and resources to the cause.

In Texas and California, Mexican Americans created new civil rights organizations in the postwar years. In Corpus Christi, Texas, World War II veterans founded the American GI Forum in 1948 to protest the poor treatment of Mexican American soldiers and veterans. Activists in Los Angeles created the Community Service Organization (CSO) the same year. Both groups arose to address specific local injustices (such as the segregation of military cemeteries), but they quickly broadened their scope to encompass political and economic justice for the larger community. Among the first young activists to work for the CSO were Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta, who would later found the United Farm Workers (UFW) and inspire the Chicano movement of the 1960s.

Activists also pushed for legal change. In 1947, five Mexican American fathers in California sued a local school district for placing their children in separate “Mexican” schools. The case, Mendez v. Westminster School District, never made it to the U.S. Supreme Court. But the Ninth Circuit Court ruled such segregation unconstitutional, laying the legal groundwork for broader challenges to racial inequality. Among those filing briefs in the case was the NAACP’s Thurgood Marshall, who was then developing the legal strategy to strike at racial segregation in the South. In another significant legal victory, the Supreme Court ruled in 1954 — just two weeks before the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision — that Mexican Americans constituted a “distinct class” that could claim protection from discrimination.

Also on the West Coast, Japanese Americans accelerated their legal challenge to discrimination. Undeterred by rulings in the Hirabayashi (1943) and Korematsu (1944) cases upholding wartime imprisonment (see “Japanese Removal” in Chapter 24), the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) filed lawsuits in the late 1940s to regain property lost during the war. The JACL also challenged the constitutionality of California’s Alien Land Law, which prohibited Japanese immigrants from owning land, and successfully lobbied Congress to enable those same immigrants to become citizens — a right they were denied for fifty years. These efforts by Mexican and Japanese Americans enlarged the sphere of civil rights and laid the foundation for a broader notion of racial equality in the postwar years.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

Question

How were the circumstances facing Mexican and Japanese Americans similar to those facing African Americans? How were they different?