America’s History: Printed Page 904

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 821

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 800

Lyndon B. Johnson and the Great Society

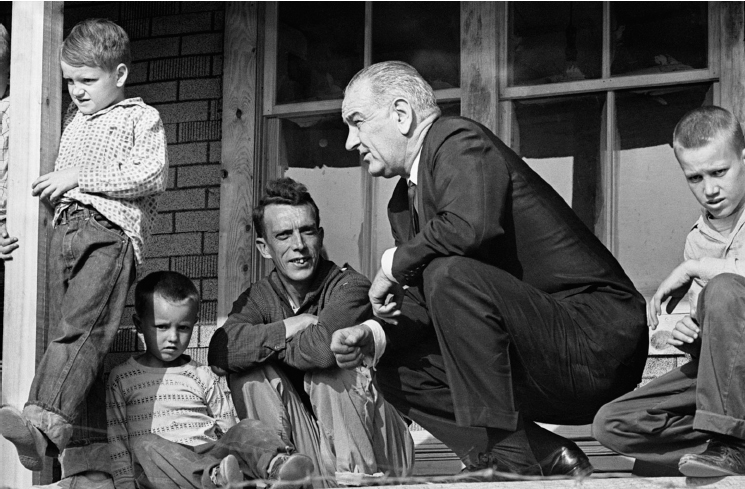

In many ways, Lyndon Johnson was the opposite of Kennedy. A seasoned Texas politician and longtime Senate leader, Johnson was most at home in the back rooms of power. He was a rough-edged character who had scrambled his way up, with few scruples, to wealth and political eminence. But he never forgot his modest, hill-country origins or lost his sympathy for the downtrodden. Johnson lacked Kennedy’s style, but he rose to the political challenge after Kennedy’s assassination, applying his astonishing energy and negotiating skills to revive several of Kennedy’s stalled programs, and many more of his own, in the ambitious Great Society.

On assuming the presidency, Johnson promptly pushed for civil rights legislation as a memorial to his slain predecessor. His motives were complex. As a southerner who had previously opposed civil rights for African Americans, Johnson wished to prove that he was more than a regional figure — he would be the president of all the people. He also wanted to make a mark on history, telling Martin Luther King Jr. and other civil rights leaders to lace up their sneakers because he would move so fast on civil rights they would be running to catch up. Politically, the choice was risky. Johnson would please the Democratic Party’s liberal wing, but because most northern African Americans already voted Democratic, the party would gain few additional votes. Moreover, southern white Democrats would likely revolt, dividing the party at a time when Johnson’s legislative agenda most required unanimity. But Johnson pushed ahead, and the 1964 Civil Rights Act stands, in part, as a testament to the president’s political risk-taking.

More than civil rights, what drove Johnson hardest was his determination to “end poverty in our time.” The president called it a national disgrace that in the midst of plenty, one-fifth of all Americans — hidden from most people’s sight in Appalachia, urban ghettos, migrant labor camps, and Indian reservations — lived in poverty. But, Johnson declared, “for the first time in our history, it is possible to conquer poverty.”

The Economic Opportunity Act of 1964, which created a series of programs to reach these Americans, was the president’s answer — what he called the War on Poverty. This legislation included several different initiatives. Head Start provided free nursery schools to prepare disadvantaged preschoolers for kindergarten. The Job Corps and Upward Bound provided young people with training and employment. Volunteers in Service to America (VISTA), modeled on the Peace Corps, offered technical assistance to the urban and rural poor. An array of regional development programs focused on spurring economic growth in impoverished areas. On balance, the 1964 legislation provided services to the poor rather than jobs, leading some critics to charge the War on Poverty with doing too little.

The 1964 Election With the Civil Rights Act passed and his War on Poverty initiatives off the ground, Johnson turned his attention to the upcoming presidential election. Not content to govern in Kennedy’s shadow, he wanted a national mandate of his own. Privately, Johnson cast himself less like Kennedy than as the heir of Franklin Roosevelt and the expansive liberalism of the 1930s. Johnson had come to Congress for the first time in 1937 and had long admired FDR’s political skills. He reminded his advisors never to forget “the meek and the humble and the lowly,” because “President Roosevelt never did.”

In the 1964 election, Johnson faced Republican Barry Goldwater of Arizona. An archconservative, Goldwater ran on an anticommunist, antigovernment platform, offering “a choice, not an echo” — meaning he represented a genuinely conservative alternative to liberalism rather than the echo of liberalism offered by the moderate wing of the Republican party during the 1950s. Goldwater campaigned against the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and promised a more vigorous Cold War foreign policy. Among those supporting him was former actor Ronald Reagan, whose speech on behalf of Goldwater at the Republican convention, called “A Time for Choosing,” made him a rising star in the party.

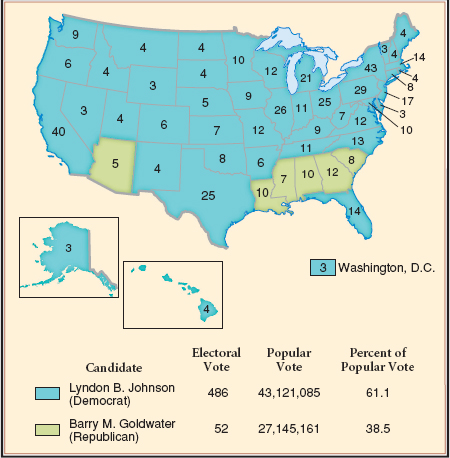

But Goldwater’s strident foreign policy alienated voters. “Extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice,” he told Republicans at the convention. Moreover, there remained strong national sentiment for Kennedy. Telling Americans that he was running to fulfill Kennedy’s legacy, Johnson and his running mate, Hubert H. Humphrey of Minnesota, won in a landslide (Map 28.1). In the long run, Goldwater’s candidacy marked the beginning of a grassroots conservative revolt that would eventually transform the Republican Party. In the short run, however, Johnson’s sweeping victory gave him a popular mandate and, equally important, congressional majorities that rivaled FDR’s in 1935 — just what he needed to push the Great Society forward (Table 28.1).

Great Society Initiatives One of Johnson’s first successes was breaking a congressional deadlock on education and health care. Passed in April 1965, the Elementary and Secondary Education Act authorized $1 billion in federal funds for teacher training and other educational programs. Standing in his old Texas schoolhouse, Johnson, a former teacher, said: “I believe no law I have signed or will ever sign means more to the future of America.” Six months later, Johnson signed the Higher Education Act, providing federal scholarships for college students. Johnson also had the votes he needed to achieve some form of national health insurance. That year, he also won passage of two new programs: Medicare, a health plan for the elderly funded by a surcharge on Social Security payroll taxes, and Medicaid, a health plan for the poor paid for by general tax revenues and administered by the states.

| Major Great Society Legislation | ||

| Civil Rights | ||

| 1964 | Twenty-fourth Amendment | Outlawed poll tax in federal elections |

| Civil Rights Act | Banned discrimination in employment and public accommodations on the basis of race, religion, sex, or national origin | |

| 1965 | Voting Rights Act | Outlawed literacy tests for voting; provided federal supervision of registration in historically low-registration areas |

| Social Welfare | ||

| 1964 | Economic Opportunity Act | Created Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO) to administer War on Poverty programs such as Head Start, Job Corps, and Volunteers in Service to America (VISTA) |

| 1965 | Medical Care Act | Provided medical care for the poor (Medicaid) and the elderly (Medicare) |

| 1966 | Minimum Wage Act | Raised hourly minimum wage from $1.25 to $1.40 and expanded coverage to new groups |

| Education | ||

| 1965 | Elementary and Secondary Education Act | Granted federal aid for education of poor children |

| National Endowment for the Arts and Humanities | Provided federal funding and support for artists and scholars | |

| Higher Education Act | Provided federal scholarships for postsecondary education | |

| Housing and Urban Development | ||

| 1964 | Urban Mass Transportation Act | Provided federal aid to urban mass transit |

| Omnibus Housing Act | Provided federal funds for public housing and rent subsidies for low-income families | |

| 1965 | Housing and Urban Development Act | Created Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) |

| 1966 | Metropolitan Area Redevelopment and Demonstration Cities Acts | Designated 150 “model cities” for combined programs of public housing, social services, and job training |

| Environment | ||

| 1964 | Wilderness Preservation Act | Designated 9.1 million acres of federal lands as “wilderness areas,” barring future roads, buildings, or commercial use |

| 1965 | Air and Water Quality Acts | Set tougher air quality standards; required states to enforce water quality standards for interstate waters |

| Miscellaneous | ||

| 1964 | Tax Reduction Act | Reduced personal and corporate income tax rates |

| 1965 | Immigration Act | Abandoned national quotas of 1924 law, allowing more non-European immigration |

| Appalachian Regional and Development Act | Provided federal funding for roads, health clinics, and other public works projects in economically depressed regions | |

The Great Society’s agenda included environmental reform as well: an expanded national park system, improvement of the nation’s air and water, protection for endangered species, stronger land-use planning, and highway beautification. Hardly pausing for breath, Johnson oversaw the creation of the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD); won funding for hundreds of thousands of units of public housing; made new investments in urban rapid transit such as the new Washington, D.C., Metro and the Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) system in San Francisco; ushered new child safety and consumer protection laws through Congress; and helped create the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities to support the work of artists, writers, and scholars.

It even became possible, at this moment of reform zeal, to tackle the nation’s discriminatory immigration policy. The Immigration Act of 1965 abandoned the quota system that favored northern Europeans, replacing it with numerical limits that did not discriminate among nations. To promote family reunification, the law also stipulated that close relatives of legal residents in the United States could be admitted outside the numerical limits, an exception that especially benefitted Asian and Latin American immigrants. Since 1965, as a result, immigrants from those regions have become increasingly visible in American society.

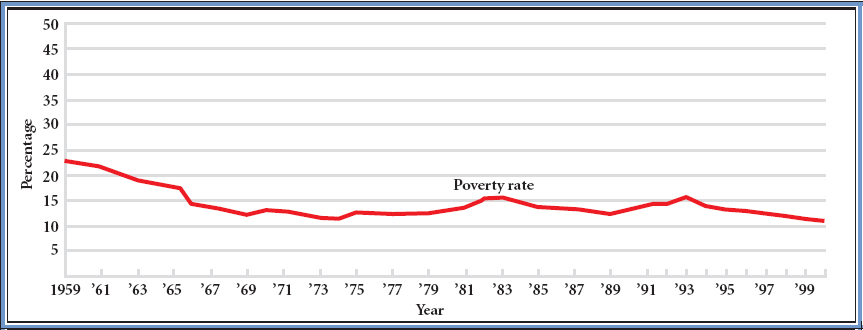

Assessing the Great Society The Great Society enjoyed mixed results. The proportion of Americans living below the poverty line dropped from 20 percent to 13 percent between 1963 and 1968 (Figure 28.1). Medicare and Medicaid, the most enduring of the Great Society programs, helped millions of elderly and poor citizens afford necessary health care. Further, as millions of African Americans moved into the middle class, the black poverty rate fell by half. Liberals believed they were on the right track.

Conservatives, however, gave more credit for these changes to the decade’s booming economy than to government programs. Indeed, conservative critics accused Johnson and other liberals of believing that every social problem could be solved with a government program. In the final analysis, the Great Society dramatically improved the financial situation of the elderly, reached millions of children, and increased the racial diversity of American society and workplaces. However, entrenched poverty remained, racial segregation in the largest cities worsened, and the national distribution of wealth remained highly skewed. In relative terms, the bottom 20 percent remained as far behind as ever. In these arenas, the Great Society made little progress.

PLACE EVENTS IN CONTEXT

Question

What new roles did the federal government assume under Great Society initiatives, and how did they extend the New Deal tradition?