America’s History: Printed Page 910

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 827

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 806

Escalation Under Johnson

Just as Kennedy had inherited Vietnam from Eisenhower, so Lyndon Johnson inherited Vietnam from Kennedy. Johnson’s inheritance was more burdensome, however, for by now only massive American intervention could prevent the collapse of South Vietnam (Map 28.2). Johnson, like Kennedy, was a subscriber to the Cold War tenets of global containment. “I am not going to lose Vietnam,” he vowed on taking office. “I am not going to be the President who saw Southeast Asia go the way China went” (see “Civil War in China” in Chapter 25).

Gulf of Tonkin It did not take long for Johnson to place his stamp on the war. During the summer of 1964, the president got reports that North Vietnamese torpedo boats had fired on the U.S. destroyer Maddox in the Gulf of Tonkin. In the first attack, on August 2, the damage inflicted was limited to a single bullet hole; a second attack, on August 4, later proved to be only misread radar sightings. To Johnson, it didn’t matter if the attack was real or imagined; the president believed a wider war was inevitable and issued a call to arms, sending his national approval rating from 42 to 72 percent. In the entire Congress, only two senators voted against his request for authorization to “take all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against the forces of the United States and to prevent further aggression.” The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, as it became known, gave Johnson the freedom to conduct operations in Vietnam as he saw fit.

Despite his congressional mandate, Johnson was initially cautious about revealing his plans to the American people. “I had no choice but to keep my foreign policy in the wings … ,” Johnson later said. “I knew that the day it exploded into a major debate on the war, that day would be the beginning of the end of the Great Society.” So he ran in 1964 on the pledge that there would be no escalation — no American boys fighting Vietnam’s fight. Privately, he doubted the pledge could be kept.

The New American Presence With the 1964 election safely behind him, Johnson began an American takeover of the war in Vietnam (American Voices). The escalation, beginning in the early months of 1965, took two forms: deployment of American ground troops and the intensification of bombing against North Vietnam.

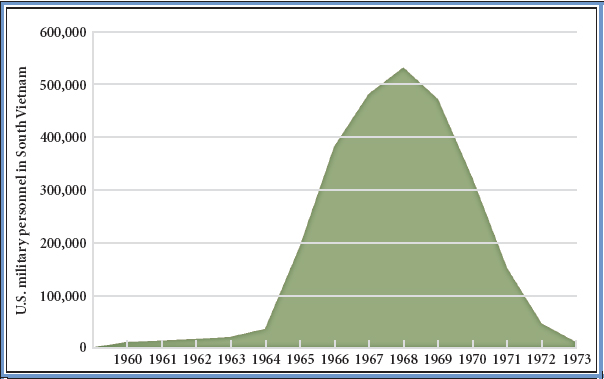

On March 8, 1965, the first marines waded ashore at Da Nang. By 1966, more than 380,000 American soldiers were stationed in Vietnam; by 1967, 485,000; and by 1968, 536,000 (Figure 28.2). The escalating demands of General William Westmoreland, the commander of U.S. forces, and Robert McNamara, the secretary of defense, pushed Johnson to Americanize the ground war in an attempt to stabilize South Vietnam. “I can’t run and pull a Chamberlain at Munich,” Johnson privately told a reporter in early March 1965, referring to the British prime minister who had appeased Hitler in 1938.

Meanwhile, Johnson authorized Operation Rolling Thunder, a massive bombing campaign against North Vietnam in 1965. Over the entire course of the war, the United States dropped twice as many tons of bombs on Vietnam as the Allies had dropped in both Europe and the Pacific during the whole of World War II. To McNamara’s surprise, the bombing had little effect on the Vietcong’s ability to wage war in the South. The North Vietnamese quickly rebuilt roads and bridges and moved munitions plants underground. Instead of destroying the morale of the North Vietnamese, Operation Rolling Thunder hardened their will to fight. The massive commitment of troops and air power devastated Vietnam’s countryside, however. After one harsh but not unusual engagement, a commanding officer reported that “it became necessary to destroy the town in order to save it” — a statement that came to symbolize the terrible logic of the war.

The Johnson administration gambled that American superiority in personnel and weaponry would ultimately triumph. This strategy was inextricably tied to political considerations. For domestic reasons, policymakers searched for an elusive middle ground between all-out invasion of North Vietnam, which included the possibility of war with China, and disengagement. “In effect, we are fighting a war of attrition,” said General Westmoreland. “The only alternative is a war of annihilation.”

UNDERSTAND POINTS OF VIEW

Question

In what larger context did President Johnson view the Vietnam conflict, and why was he determined to support South Vietnam?