America’s History: Printed Page 1025

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 931

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 907

The Ascendance of George W. Bush

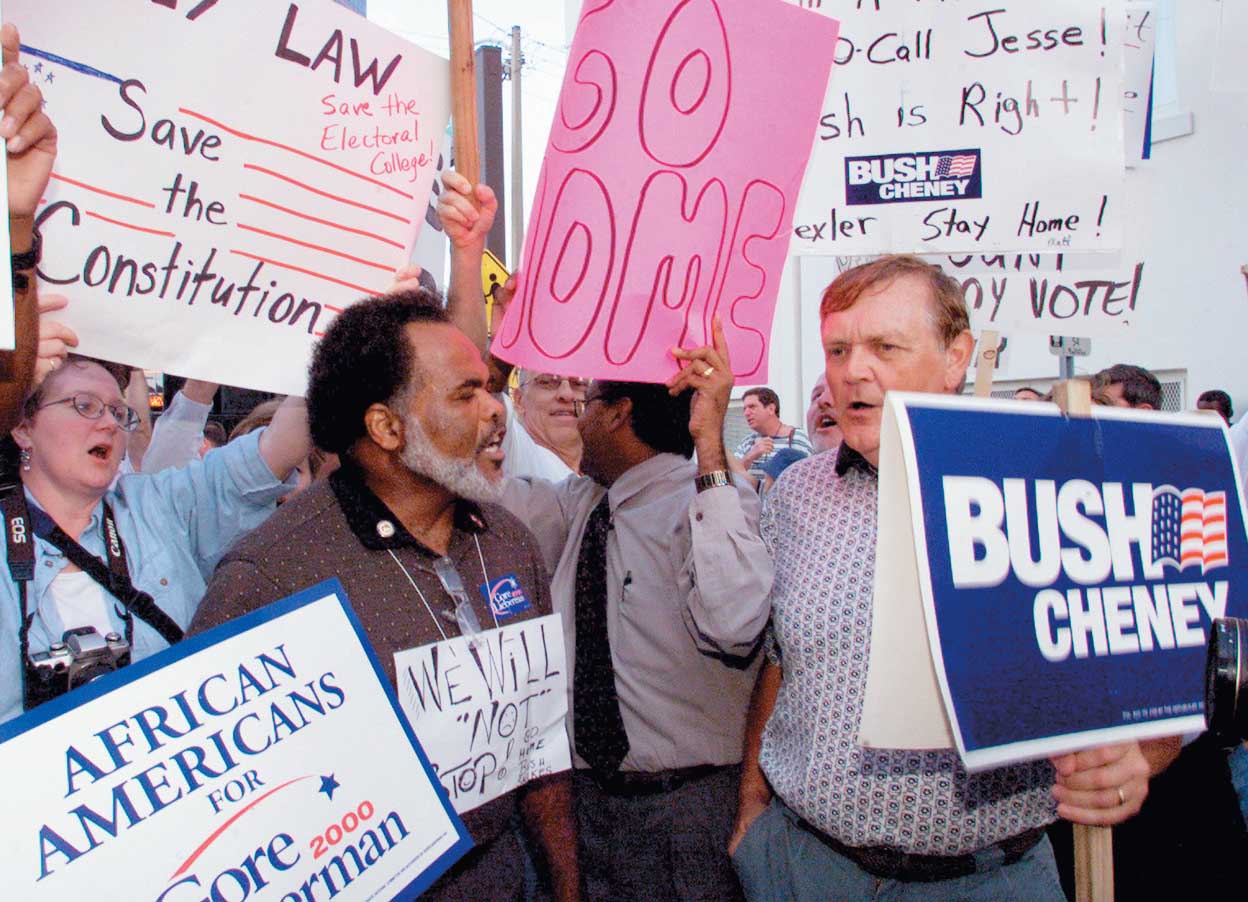

The 2000 presidential election briefly offered the promise of a break with the intense partisanship of the final Clinton years. The Republican nominee, George W. Bush, the son of President George H. W. Bush, presented himself as an outsider, deploring Washington partisanship and casting himself as a “uniter, not a divider.” His opponent, Al Gore — Clinton’s vice president — was a liberal policy specialist. The election of 2000 would join those of 1876 and 1960 as the closest and most contested in American history. Gore won the popular vote, amassing 50.9 million votes to Bush’s 50.4 million, but fell short in the electoral college, 267 to 271. Consumer- and labor-rights activist Ralph Nader ran as the Green Party candidate and drew away precious votes in key states that certainly would have carried Gore to victory.

Late on election night, the vote tally in Florida gave Bush the narrowest of victories. As was their legal prerogative, the Democrats demanded hand recounts in several counties. A month of tumult followed, until the U.S. Supreme Court, voting strictly along conservative/liberal lines, ordered the recount stopped and let Bush’s victory stand. Recounting ballots without a consistent standard to determine “voter intent,” the Court reasoned, violated the rights of Floridian voters under the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause. As if acknowledging the frailty of this argument, the Court declared that Bush v. Gore was not to be regarded as precedent. But in a dissenting opinion, Justice John Paul Stevens warned that the transparently partisan decision undermined “the Nation’s confidence in the judge as an impartial guardian of the rule of law.”

Although Bush had positioned himself as a moderate, countertendencies drove his administration from the start. His vice president, the uncompromising conservative Richard (Dick) Cheney, became, with Bush’s consent, virtually a copresident. Bush also brought into the administration his campaign advisor, Karl Rove, whose advice made for an exceptionally politicized White House. Rove foreclosed the easygoing centrism of Bush the campaigner by arguing that a permanent Republican majority could be built on the party’s conservative base. On Capitol Hill, Rove’s hard line was reinforced by Tom DeLay, the House majority leader, who in 1995 had declared “all-out war” on the Democrats. To win that war, DeLay pushed congressional Republicans to endorse a fierce partisanship. The Senate, although more collegial, went through a similar hardening process. After 2002, with Republicans in control of both Congress and the White House, bipartisan lawmaking came to an end.

Tax Cuts The domestic issue that most engaged President Bush, as it had Ronald Reagan, was taxes. Bush’s Economic Growth and Tax Relief Act of 2001 had something for everyone. It slashed income tax rates, extended the earned income credit for the poor, and marked the estate tax to be phased out by 2010. A second round of cuts in 2003 targeted dividend income and capital gains. Bush’s signature cuts — those favoring big estates and well-to-do owners of stocks and bonds — skewed the distribution of tax benefits upward (Table 31.1). Bush had pushed far beyond any other postwar president, even Reagan, in slashing federal taxes.

| Impact of the Bush Tax Cuts, 2001–2003 | ||||||

| Income in 2003 | Taxpayers | Gross Income | Total Tax Cut | % Change in Tax Bill |

Tax Bill | Tax Rate |

| Less than $50,000 | 92,093,452 | $19,521 | $435 | –48% | $474 | 2% |

| $50,000 to 100,000 | 26,915,091 | 70,096 | 1,656 | –21 | 6,417 | 9 |

| $100,000 to 200,000 | 8,878,643 | 131,797 | 3,625 | –17 | 18,281 | 14 |

| $200,000 to 500,000 | 1,999,061 | 288,296 | 7,088 | –10 | 60,464 | 21 |

| $500,000 to 1,000,000 | 356,140 | 677,294 | 22,479 | –12 | 169,074 | 25 |

| $1,000,000 to 10,000,000 | 175,157 | 2,146,100 | 84,666 | –13 | 554,286 | 26 |

| $10,000,000 or more | 6,126 | 25,975,532 | 1,019,369 | –15 | 5,780,926 | 22 |

|

SOURCE: New York Times, April 5, 2006. |

||||||

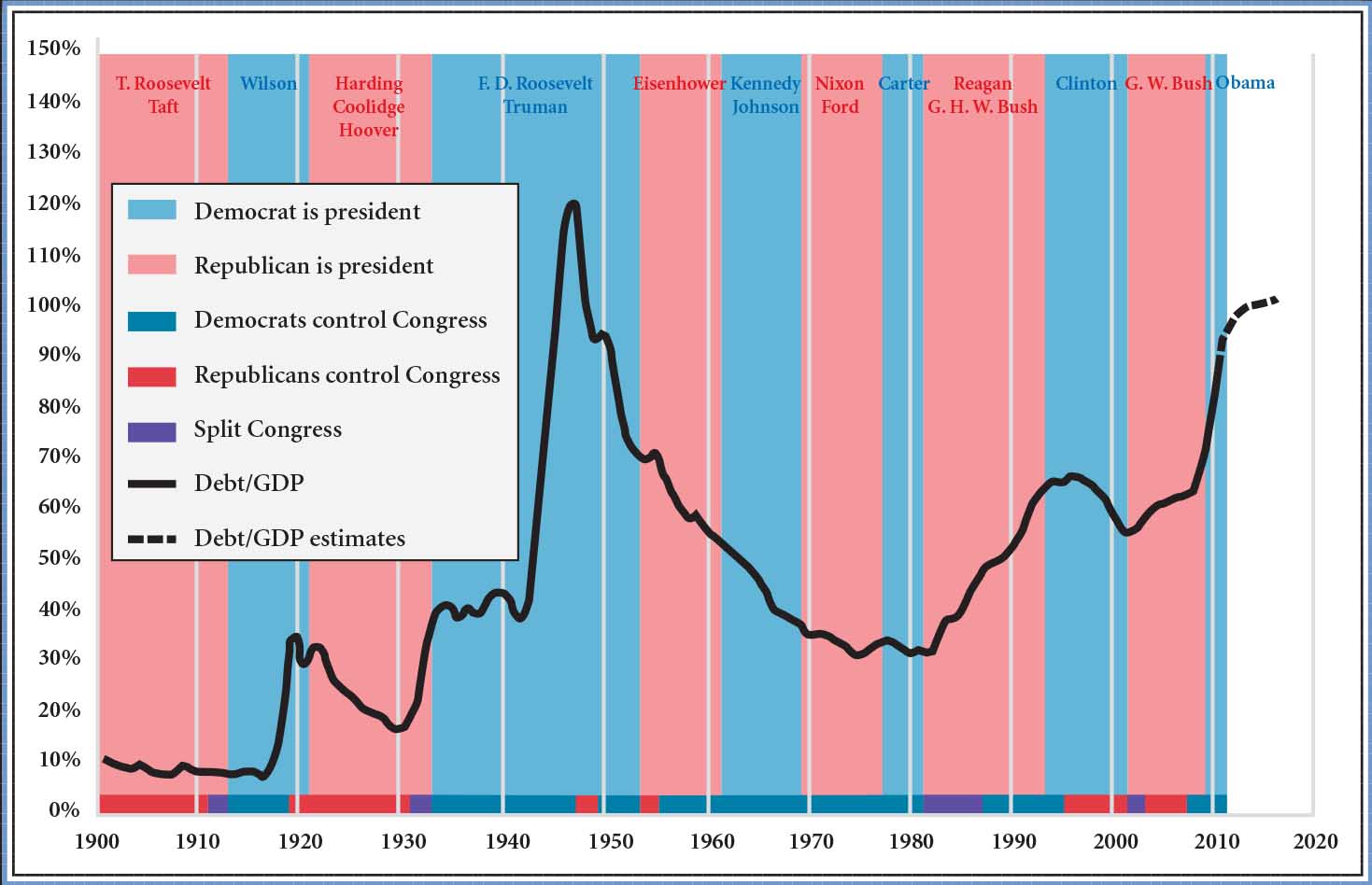

Critics warned that such massive tax cuts would plunge the federal government into debt. By 2006, federal expenditures had jumped 33 percent, at a faster clip than under any president since Lyndon Johnson. Huge increases in health-care costs were the main culprit. Two of the largest federal programs, Medicare and Medicaid — health care for the elderly and the poor, respectively — could not contain runaway medical costs. Midway through Bush’s second term, the national debt stood at over $8 trillion — much of it owned by foreign investors, who also financed the nation’s huge trade deficit. On top of that, staggering Social Security and Medicare obligations were coming due for retiring baby boomers. It seemed that these burdens would be passed on to future generations (Figure 31.6).

September 11, 2001 How Bush’s presidency might have fared in normal times is another of those unanswerable questions of history. As a candidate in 2000, George W. Bush had said little about foreign policy. He had assumed that his administration would rise or fall on his domestic program. But nine months into his presidency, an altogether different political scenario unfolded. On a sunny September morning, nineteen Islamic terrorists from Al Qaeda hijacked four commercial jets and flew two of them into New York City’s World Trade Center, destroying its twin towers and killing more than 2,900 people. A third plane crashed into the Pentagon, near Washington, D.C. The fourth, presumably headed for the White House or possibly the U.S. Capitol, crashed in Pennsylvania when the passengers fought back and thwarted the hijackers. As an outburst of patriotism swept the United States in the wake of the September 11 attacks, George W. Bush proclaimed a “war on terror” and vowed to carry the battle to Al Qaeda.

Operating out of Afghanistan, where they had been harbored by the fundamentalist Taliban regime, the elusive Al Qaeda briefly offered a clear target. In October 2001, while Afghani allies carried the ground war, American planes attacked the enemy. By early 2002, this lethal combination had ousted the Taliban, destroyed Al Qaeda’s training camps, and killed or captured many of its operatives. However, the big prize, Al Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden, had retreated to a mountain redoubt. Inexplicably, U.S. forces failed to press the attack, and bin Laden escaped over the border into Pakistan.

The Invasion of Iraq On the domestic side, Bush declared the terrorist threat too big to be contained by ordinary law-enforcement means. He wanted the government’s powers of domestic surveillance placed on a wartime footing. With little debate, in 2001 Congress passed the USA PATRIOT Act, granting the administration sweeping authority to monitor citizens and apprehend suspected terrorists. On the international front, Bush used the war on terror as the premise for a new policy of preventive war. Under international law, only an imminent threat justified a nation’s right to strike first. Now, under the so-called Bush doctrine, the United States lowered the bar. It reserved for itself the right to act in “anticipatory self-defense.” In 2002, President Bush singled out Iran, North Korea, and Iraq — “an axis of evil” — as the targeted states.

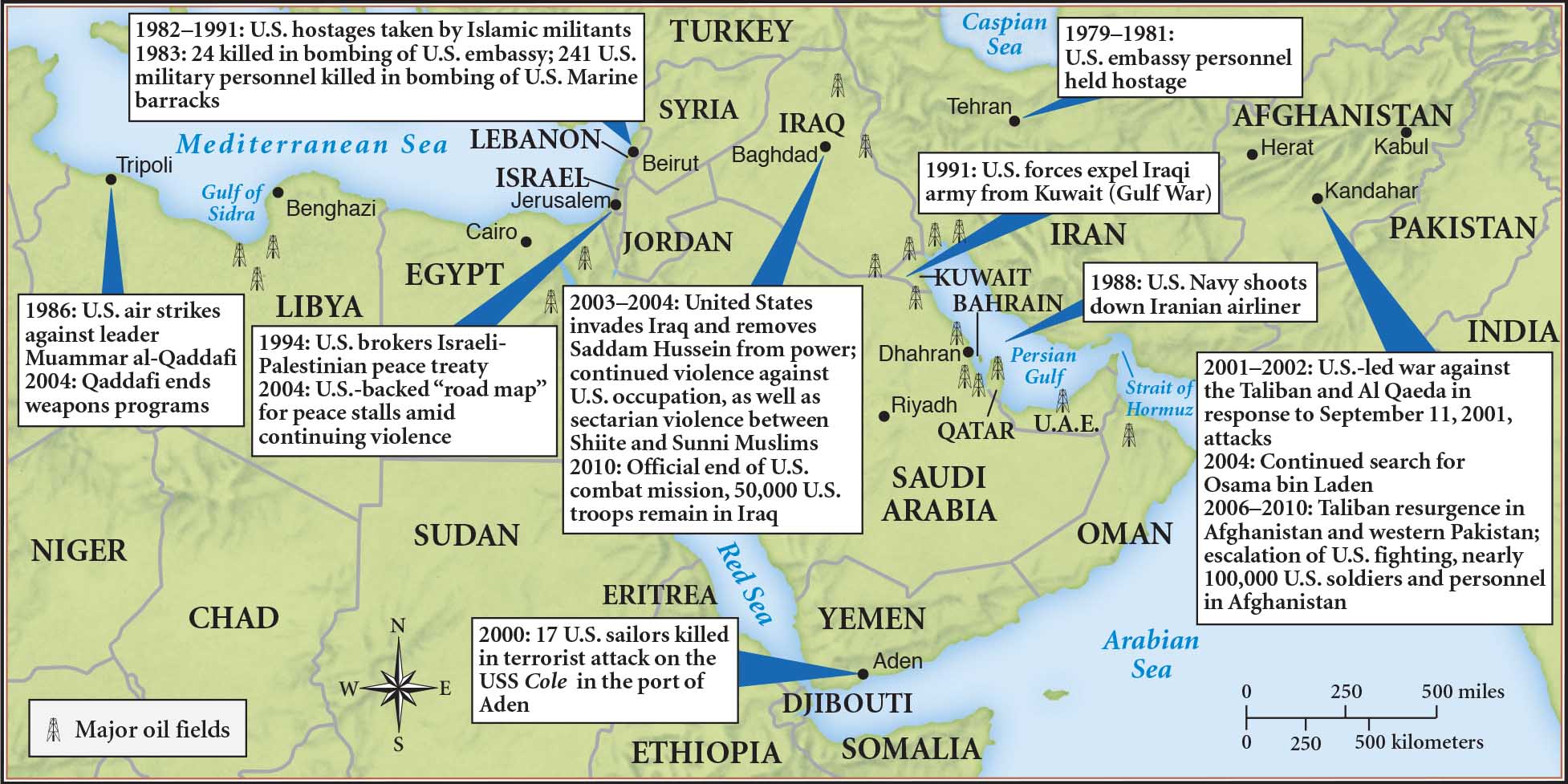

Of the three, Iraq was the preferred mark. Officials in the Pentagon regarded Iraq as unfinished business, left over from the Gulf War of 1991. More grandly, they saw in Iraq an opportunity to unveil America’s supposed mission to democratize the world. Iraqis, they believed, would abandon the tyrant Saddam Hussein and embrace democracy if given the chance. The democratizing effect would spread across the Middle East, toppling or reforming other unpopular Arab regimes and stabilizing the region. That, in turn, would secure the Middle East’s oil supply, whose fragility Saddam’s 1990 invasion of Kuwait had made all too clear. It was the oil, in the end, that was of vital interest to the United States (Map 31.4).

None of these considerations, either singly or together, met Bush’s declared threshold for preventive war. So the president reluctantly acceded to the demand by America’s anxious European allies that the United States go to the UN Security Council, which demanded that Saddam Hussein allow the return of the UN weapons inspectors expelled in 1998. Saddam surprisingly agreed. Nevertheless, anxious to invade Iraq for its own reasons, the Bush administration geared up for war. Insisting that Iraq constituted a “grave and gathering danger” and ignoring its failure to secure a second, legitimizing UN resolution, Bush invaded in March 2003. America’s one major ally in the rush to war was Great Britain. Relations with France and Germany became poisonous. Even neighboring Mexico and Canada condemned the invasion, and Turkey, a key military ally, refused transit permission, ruining the army’s plan for a northern thrust into Iraq. As for the Arab world, it exploded in anti-American demonstrations.

Within three weeks, American troops had taken the Iraqi capital. The regime collapsed, and its leaders went into hiding (Saddam Hussein was captured nine months later). But despite meticulous military planning, the Pentagon had made no provision for postconflict operations. Thousands of poor Iraqis looted everything they could get their hands on, shattering the infrastructure of Iraq’s cities and leaving them without reliable supplies of electricity and water. In the midst of this turmoil, an insurgency began, sparked by Sunni Muslims who had dominated Iraq under Saddam’s Baathist regime.

Iraq’s Shiite majority, long oppressed by Saddam, at first welcomed the Americans, but extremist Shiite elements soon turned hostile, and U.S. forces found themselves under fire from both sides. With the borders unguarded, Al Qaeda supporters flocked in from all over the Middle East, eager to do battle with the infidel Americans, bringing along a specialty of the jihad: the suicide bomber.

Blinded by their own nationalism, dominant nations tend to underestimate the strength of nationalism in other people. Lyndon Johnson discovered this in Vietnam. Soviet premier Leonid Brezhnev discovered it in Afghanistan. And George W. Bush rediscovered it in Iraq. Although it was hard for Americans to believe, Iraqis of all stripes viewed the U.S. forces as invaders. Moreover, in a war against insurgents, no occupation force comes out with clean hands. In 2004 in Iraq, that painful truth burst forth graphically in photographs showing American guards at Baghdad’s Abu Ghraib prison abusing and torturing suspected insurgents. The ghastly images shocked the world. For Muslims, they offered final proof of American treachery. At that low point, in 2004, the United States had spent upward of $100 billion. More than 1,000 American soldiers had died, and 10,000 others had been wounded, many maimed for life. But if the United States pulled out, Iraq would descend into chaos. So, as Bush took to saying, the United States had to “stay the course.”

The 2004 Election As the 2004 presidential election approached, Rove, Bush’s top advisor, theorized that stirring the culture wars and emphasizing patriotism and Bush’s war on terror would mobilize conservatives to vote for Bush. Rove encouraged activists to place antigay initiatives on the ballot in key states to draw conservative voters to the polls; in all, eleven states would pass ballot initiatives that wrote bans on gay marriage equality into state constitutions that year. The Democratic nominee, Senator John Kerry of Massachusetts, was a Vietnam hero, twice wounded and decorated for bravery — in contrast to the president, who had spent the Vietnam years comfortably in the Texas Air National Guard. But when Kerry returned from service in Vietnam, he had joined the antiwar group Vietnam Veterans Against the War and in 1971 had delivered a blistering critique of the war to the Senate Armed Services Committee. In the logic of the culture wars, this made him vulnerable to charges of being weak and unpatriotic.

The Democratic convention in August was a tableau of patriotism, filled with waving flags, retired generals, and Kerry’s Vietnam buddies. However, a sudden onslaught of slickly produced television ads by a group calling itself Swift Boat Veterans for Truth, falsely charging that Kerry had lied to win his medals, fatally undercut his advantage. Nor did it help that Kerry, as a three-term senator, had a lengthy record that was easily mined for hard-to-explain votes. Republicans tagged him a “flip-flopper,” and the accusation, endlessly repeated, stuck. Nearly 60 percent of eligible voters — the highest percentage since 1968 — went to the polls. Bush beat Kerry, with 286 electoral votes to Kerry’s 252. In exit polls, Bush did well among voters for whom moral “values” and national security were top concerns. Voters told interviewers that Bush made them feel “safer.” Bush was no longer a minority president. He had won a clear, if narrow, popular majority.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

Question

In what ways was George H. W. Bush a political follower of Ronald Reagan (Chapter 30)? In what ways was he not?