America’s History: Printed Page 1004

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 912

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 891

America in the Global Economy

On November 30, 1999, more than 50,000 protesters took to the streets of Seattle, Washington, immobilizing a wide swath of the city’s downtown. Police, armed with pepper spray and arrayed in riot gear, worked feverishly to clear the clogged streets, get traffic moving, and usher well-dressed government ministers from around the world into a conference hall. Protesters jeered, chanted, and held hundreds of signs and banners aloft. A radical contingent joined the otherwise peaceful march, and a handful of them began breaking the windows of the chain stores they saw as symbols of global capitalism: Starbucks, Gap, Old Navy.

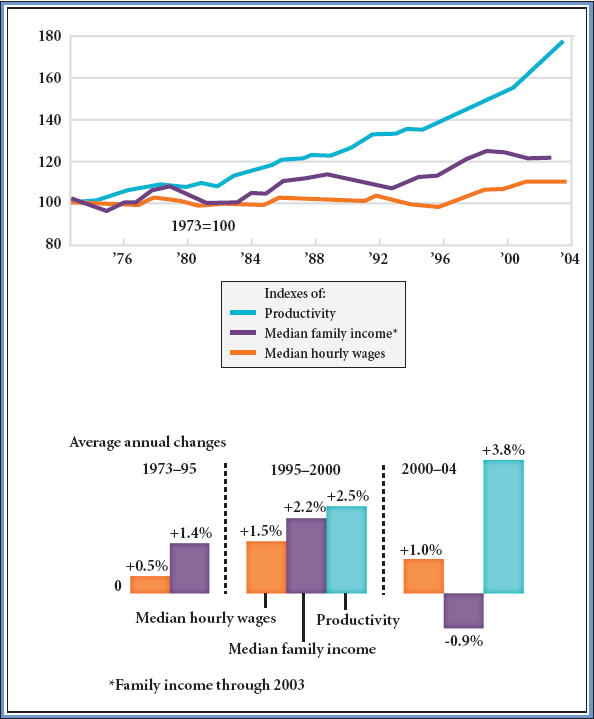

What had aroused such passion in the so-called Battle of Seattle? Globalization. The vast majority of Americans never surged into the streets, as had the Seattle protesters who tried to shut down this 1999 meeting of the World Trade Organization (WTO), but no American by the late 1990s could deny that developments in the global economy reverberated at home. In that decade, Americans rediscovered a long-standing truth: the United States was not an island, but was linked in countless different ways to a global economy and society. Economic prosperity in the post-World War II decades had obscured for Americans this fundamental reality (Figure 31.1).

Globalization saw the rapid spread of capitalism around the world, huge increases in global trade and commerce, and a diffusion of communications technology, including the Internet, that linked the world’s people to one another in ways unimaginable a generation earlier (Thinking Like a Historian). Suddenly, the United States faced a dizzying array of opportunities and challenges, both at home and abroad. “Profound and powerful forces are shaking and remaking our world,” said a young President Bill Clinton in his first inaugural address in 1993. “The urgent question of our time is whether we can make change our friend and not our enemy.”

An additional question remained, however. In whose interest was the global economy structured? Many of the Seattle activists took inspiration from the five-point “Declaration for Global Democracy,” issued by the human rights organization Global Exchange during the WTO’s Seattle meeting. “Global trade and investment,” the declaration demanded, “must not be ends in themselves but rather the instruments for achieving equitable and sustainable development, including protections for workers and the environment.” The declaration also addressed inequality among nations, calling attention to who benefitted from globalization and who did not.