America’s History: Printed Page 271

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 245

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 238

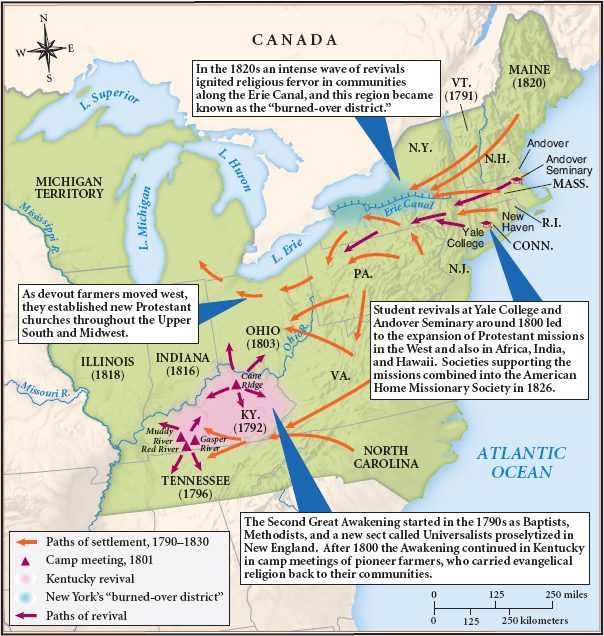

The Second Great Awakening

As Americans adopted new religious principles, a decades-long series of religious revivals — the Second Great Awakening — made the United States a genuinely Christian society. Evangelical denominations began the revival in the 1790s, as they spread their message in seacoast cities and the backcountry of New England. A new sect of Universalists, who repudiated Calvinism and preached universal salvation, also gained tens of thousands of converts, especially in Massachusetts and northern New England. After 1800, enthusiastic camp meetings swept the frontier regions of South Carolina, Tennessee, Ohio, and Kentucky. The largest gathering, at Cane Ridge in Kentucky in 1801, lasted for nine electrifying days and nights and attracted almost 20,000 people (Map 8.4). With these revivals, Baptist and Methodist preachers reshaped the spiritual landscape throughout the South. Offering a powerful emotional message and the promise of religious fellowship, revivalists attracted both unchurched individuals and pious families searching for social ties as they migrated to new communities (America Compared).

A New Religious Landscape The Second Great Awakening transformed the denominational makeup of American religion. The main colonial-period churches — the Congregationalists, Episcopalians, and Quakers — grew slowly through natural increase, while Methodist and Baptist churches expanded spectacularly by winning converts. In rural areas, their preachers followed a regular circuit, “riding a hardy pony or horse” with their “Bible, hymn-book, and Discipline” to visit existing congregations. They began new churches by searching out devout families, bringing them together for worship, and then appointing lay elders to lead the congregation and enforce moral discipline. Soon, Baptists and Methodists were the largest denominations.

To attract converts, evangelical ministers copied the “practical preaching” techniques of George Whitefield and other eighteenth-century revivalists. They spoke from memory in plain language, raised their voice to make important points, and punctuated their words with theatrical gestures. “Preach without papers,” advised one minister. “[S]eem earnest & serious; & you will be listened to with Patience, & Wonder.”

In the South, evangelical religion was initially a disruptive force because many ministers spoke of spiritual equality and criticized slavery. Husbands and planters grew angry when their wives became more assertive and when blacks joined evangelical congregations. To retain white men in their churches, Methodist and Baptist preachers gradually adapted their religious message to justify the authority of yeomen patriarchs and slave-owning planters. Man was naturally at “the head of the woman,” declared one Baptist minister, while a Methodist conference told Christian slaves to be “submissive, faithful, and obedient.”

Black Christianity Other evangelists persuaded planters to spread Protestant Christianity among their African American slaves. During the eighteenth century, most blacks had maintained the religious practices of their African homelands, giving homage to African gods and spirits or practicing Islam. “At the time I first went to Carolina,” remembered former slave Charles Ball, “there were a great many African slaves in the country. … Many of them believed there were several gods [and] I knew several … Mohamedans.” Beginning in the mid-1780s, Baptist and Methodist preachers converted hundreds of African Americans along the James River in Virginia and throughout the Chesapeake and the Carolinas.

Subsequently, black Christians adapted Protestant teachings to their own needs. They generally ignored the doctrines of original sin and Calvinist predestination as well as biblical passages that prescribed unthinking obedience to authority. Some African American converts envisioned the Christian God as a warrior who had liberated the Jews. Their own “cause was similar to the Israelites,” preacher Martin Prosser told his fellow slaves as he and his brother Gabriel plotted rebellion in Virginia in 1800. “I have read in my Bible where God says, if we worship him, … five of you shall conquer a hundred and a hundred of you a hundred thousand of our enemies.” Confident of a special relationship with God, Christian slaves prepared themselves spiritually for emancipation, the first step in their journey to the Promised Land.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

Question

How did evangelical and African American churches differ from other Protestant denominations?