America’s History: Printed Page 273

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 248

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 240

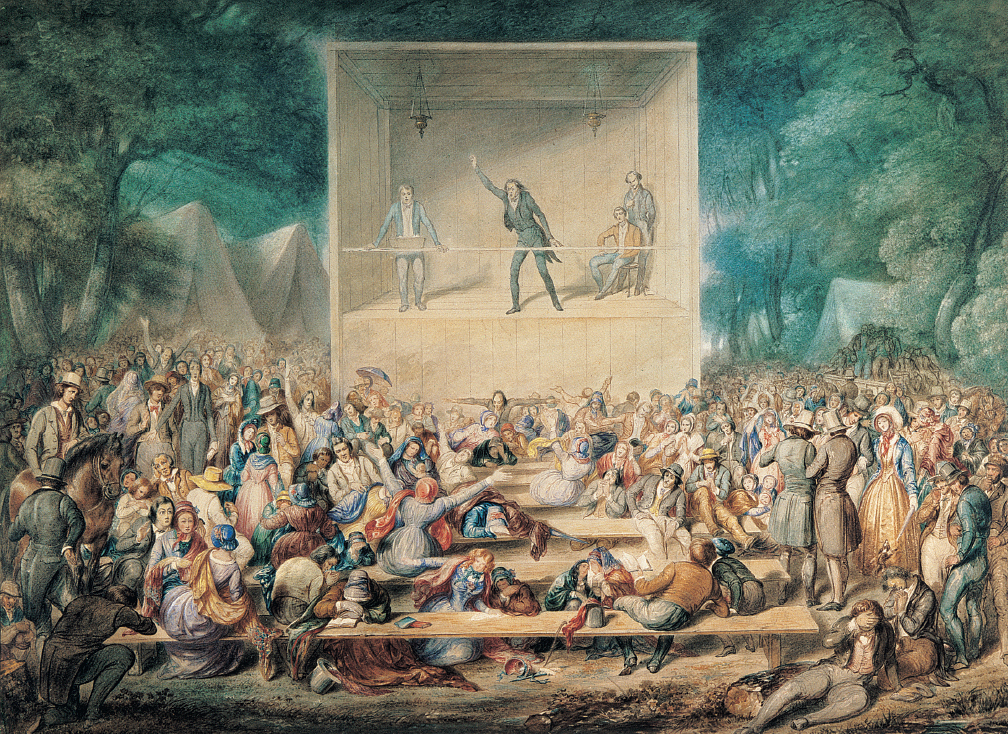

Religion and Reform

Many whites also rejected the Calvinists’ emphasis on human depravity and weakness; instead, they celebrated human reason and free will. In New England, educated Congregationalists discarded the mysterious concept of the Trinity — Father, Son, and Holy Spirit — and, taking the name Unitarians, worshipped a “united” God and promoted rational thought. “The ultimate reliance of a human being is, and must be, on his own mind,” argued William Ellery Channing, a famous Unitarian minister. A children’s catechism conveyed the denomination’s optimistic message: “If I am good, God will love me, and make me happy.”

Other New England Congregationalists softened Calvinist doctrines. Lyman Beecher, the preeminent Congregationalist clergyman, accepted the traditional Christian belief that people had a natural tendency to sin; but, rejecting predestination, he affirmed the capacity of all men and women to choose God. By embracing the doctrine of free will, Beecher — along with “Free Will” Baptists — testified to the growing belief that people could shape their destiny.

Reflecting this optimism, the Reverend Samuel Hopkins linked individual salvation to religious benevolence — the practice of disinterested virtue. As the Presbyterian minister John Rodgers explained, fortunate individuals who had received God’s grace or bounty had a duty “to dole out charity to their poorer brothers and sisters.” Heeding this message, pious merchants in New York City founded the Humane Society and other charitable organizations. Devout women aided their ministers by holding prayer meetings and distributing charity. By the 1820s, so many Protestant men and women had embraced benevolent reform that conservative church leaders warned them not to neglect spiritual matters. Still, improving society was a key element of the new religious sensibility. The mark of a true church, declared the devout Christian social reformer Lydia Maria Child, is when members’ “heads and hearts unite in working for the welfare of the human-race.”

By the 1820s, many Protestant Christians had embraced that goal. Unlike the First Great Awakening, which split churches into warring factions, the Second Great Awakening fostered cooperation among denominations. Religious leaders founded five interdenominational societies: the American Education Society (1815), the Bible Society (1816), the Sunday School Union (1824), the Tract Society (1825), and the Home Missionary Society (1826). Based in eastern cities — New York, Boston, and Philadelphia — these societies dispatched hundreds of missionaries to the West and distributed thousands of religious pamphlets.

Increasingly, American Protestants saw themselves as a movement that could change the course of history. “I want to see our state evangelized,” declared a churchgoer near the Erie Canal: “Suppose the great State of New York in all its physical, political, moral, commercial, and pecuniary resources should come over to the Lord’s side. Why it would turn the scale and could convert the world. I shall have no rest until it is done.”

Because the Second Great Awakening aroused such enthusiasm, religion became an important new force in political life. On July 4, 1827, the Reverend Ezra Stiles Ely called on the Philadelphia Presbyterians to begin a “Christian party in politics.” Ely’s sermon, “The Duty of Christian Freemen to Elect Christian Rulers,” proclaimed a religious agenda for the American republic that Thomas Jefferson and John Adams would have found strange and troubling. The two founders had gone to their graves the previous year believing that America’s mission was to spread political republicanism. In contrast, Ely urged the United States to become an evangelical Christian nation dedicated to religious conversion at home and abroad: “All our rulers ought in their official capacity to serve the Lord Jesus Christ.” Evangelical Christians would issue similar calls during the Third (1880–1900) and Fourth (1970–present) Great Awakenings.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

Question

How was the Second Great Awakening similar to, and different from, the First Great Awakening of the 1740s?