America’s History: Printed Page 250

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 225

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 219

Banks, Manufacturing, and Markets

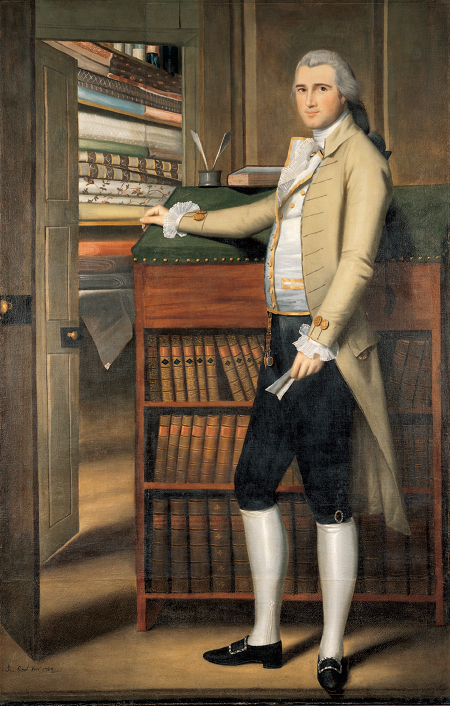

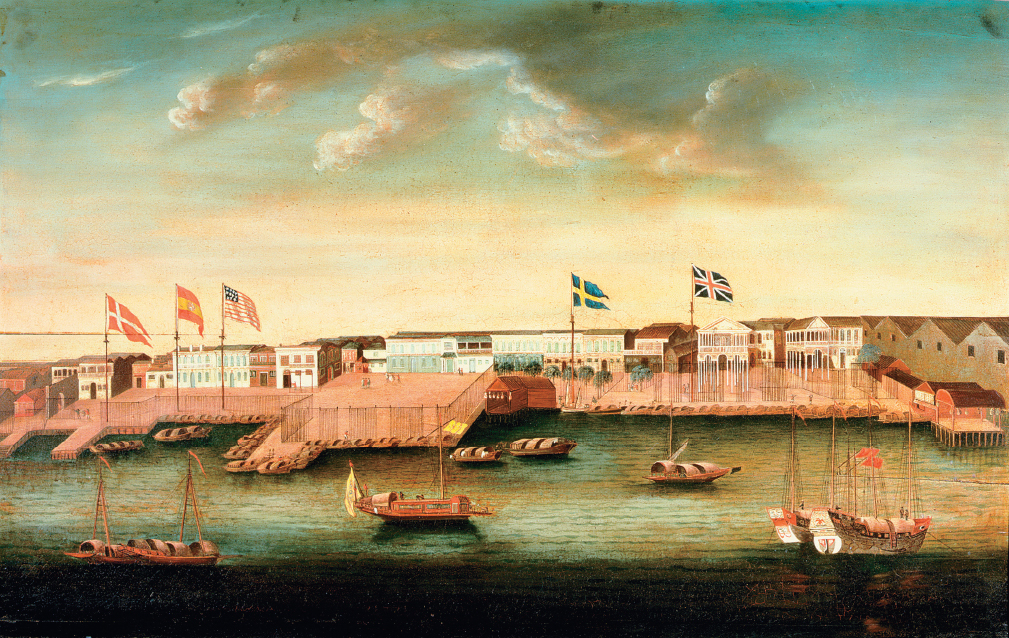

America was “a Nation of Merchants,” a British visitor reported from Philadelphia in 1798, “keen in the pursuit of wealth in all the various modes of acquiring it.” Acquire it they did, making spectacular profits as the wars of the French Revolution and Napoleon (1793–1815) crippled European firms. Merchants John Jacob Astor and Robert Oliver became the nation’s first millionaires. After working for an Irish-owned linen firm in Baltimore, Oliver struck out on his own, achieving affluence by trading West Indian sugar and coffee. Astor, who migrated from Germany to New York in 1784, began by selling dry-goods in western New York and became wealthy by carrying furs from the Pacific Northwest to China and investing in New York City real estate (Thinking Like a Historian).

Banking and Credit To finance their ventures, Oliver, Astor, and other merchants needed capital, from either their own savings or loans. Before the Revolution, farmers relied on government-sponsored land banks for loans, while merchants arranged partnerships or obtained credit from British suppliers. Then, in 1781, Philadelphia merchants persuaded the Confederation Congress to charter the Bank of North America, and traders in Boston and New York soon founded similar institutions that raised funds and lent them out. “Our monied capital has so much increased from the Introduction of Banks, & the Circulation of the Funds,” Philadelphia merchant William Bingham boasted in 1791, “that the Necessity of Soliciting Credits from England will no longer exist.”

That same year, Federalists in Congress chartered the Bank of the United States to issue notes and make commercial loans. By 1805, the bank had branches in eight seaport cities, profits that averaged a handsome 8 percent annually, and clients with easy access to capital. As trader Jesse Atwater noted, “the foundations of our [merchant] houses are laid in bank paper.”

However, Jeffersonians attacked the bank as an unconstitutional expansion of federal power. Moreover, they claimed it promoted “a consolidated, energetic government supported by public creditors, speculators, and other insidious men.” When the bank’s twenty-year charter expired in 1811, the Jeffersonian Republican-dominated Congress refused to renew it. Merchants, artisans, and farmers quickly persuaded state legislatures to charter banks — in Pennsylvania, no fewer than 41. By 1816, when Congress (now run by National Republicans) chartered a new national bank (known as the Second Bank of the United States), there were 246 state-chartered banks with tens of thousands of stockholders and $68 million in banknotes in circulation. These state banks were often shady operations that issued notes without adequate specie reserves, made loans to insiders, and lent generously to farmers buying overpriced land.

Dubious banking policies helped bring on the Panic of 1819 (just as they caused the financial crisis of 2008), but broader forces were equally important. As the Napoleonic Wars ended in 1815, Americans sharply increased their consumption of English woolen and cotton goods. However, in 1818, farmers and planters faced an abrupt 30 percent drop in world agricultural prices. The price of raw cotton in South Carolina fell from 34 to 15 cents a pound, and as Britain closed the West Indies to American trade, wheat prices plummeted as well. As farmers’ income declined, they could not pay debts owed to stores and banks, many of which went bankrupt. “A deep shadow has passed over our land,” lamented one New Yorker, as land prices dropped by 50 percent. The panic gave Americans their first taste of a business cycle, the periodic boom and bust inherent to an unregulated market economy.

Rural Manufacturing The Panic of 1819 devastated artisans and farmers who sold goods in regional or national markets. Before 1800, many artisans worked part-time and bartered their handicrafts locally. A French traveler in Massachusetts found many “men who are both cultivators and artisans,” while in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, clockmaker John Hoff exchanged his clocks for a dining table, a bedstead, and labor on his small farm. Then various artisans — shipbuilders in seacoast towns, ironworkers in Pennsylvania and Maryland, clockmakers in Connecticut, and shoemakers in Massachusetts — expanded their output and sold their products in wider markets.

American entrepreneurs drove this expansion of rural manufacturing. Beginning in the 1790s, enterprising merchants bought raw materials, hired farm families to process them, and distributed the finished manufactures. “Straw hats and Bonnets are manufactured by many families,” a Maine census-taker noted in the 1810s. Merchants shipped rural manufactures — shoes, brooms, and palm-leaf hats as well as cups, baking pans, and other tin utensils — to stores in seaport cities. New England peddlers, who quickly acquired repute as hard-bargaining “Yankees,” sold them throughout the rural South.

New technology initially played only a minor role in producing this boom in consumer goods. Take the case of textile production. During the 1780s, New England and Middle Atlantic merchants built water-powered mills to run machines that combed wool — and later cotton — into long strands. However, until the 1810s, they used the household-based outwork system for the next steps: farm women and children spun the machine-combed strands into thread and yarn on foot-driven spinning wheels, and men in other households used foot-powered looms to weave the yarn into cloth. In 1820, more than 12,000 household workers labored full-time weaving woolen cloth, which water-powered fulling mills then pounded flat, giving the cloth a smooth finish. By then, the transfer of textile production to factories was gaining speed; the number of water-driven cotton spindles soared from 8,000 in 1809 to 333,000 in 1817.

The growth of manufacturing offered farm families new opportunities — and new risks. Ambitious New England farmers switched from subsistence crops of wheat and potatoes to raising livestock. They sold meat, butter, and cheese to city markets and cattle hides to the booming shoe industry. “Along the whole road from Boston, we saw women engaged in making cheese,” a Polish traveler reported. Other families raised sheep and sold raw wool to textile manufacturers. Processing these raw materials brought new jobs and income to stagnating farming towns. In 1792, Concord, Massachusetts, had one slaughterhouse and five small tanneries; a decade later, the town boasted eleven slaughterhouses and six large tanneries.

As the rural economy churned out more goods, it altered the environment. Foul odors from stockyards and tanning pits wafted over Concord and other leather-producing towns. Nor was that all. Tanners cut down thousands of acres of hemlock trees, using the bark to process stiff cow hides into pliable leather. More trees fell to the ax to create pasturelands for huge herds of livestock — dairy cows, cattle, and especially sheep. By 1850, most of the ancient forests in southern New England and eastern New York were gone: “The hills had been stripped of their timber,” New York’s Catskill Messenger reported, “so as to present their huge, rocky projections.” Moreover, scores of textile milldams dotted New England’s rivers, altering their flow and preventing fish — already severely depleted from decades of overfishing — from reaching upriver spawning grounds. Even as the income of farmers rose, the quality of their natural environment declined.

In the new capitalist-driven market economy, rural parents and their children worked longer and harder. They made yarn, hats, and brooms during the winter and returned to their regular farming chores during the warmer seasons. More important, these farm families now depended on their wage labor or market sales to purchase the textiles, shoes, and hats they had once made for themselves. The new productive system made families and communities more efficient and prosperous — and more dependent on a market they could not control.

New Transportation Systems The expansion of the market depended on improvements in transportation, where governments also played a crucial role. Between 1793 and 1812, the Massachusetts legislature granted charters to more than one hundred private turnpike corporations. These charters gave the companies special legal status and often included monopoly rights to a transportation route. Pennsylvania issued fifty-five charters, including one to the Lancaster Turnpike Company, which built a 65-mile graded and graveled toll road to Philadelphia. The road quickly boosted the regional economy. Although turnpike investors received only about “three percent annually,” Henry Clay estimated, society as a whole “actually reap[ed] fifteen or twenty percent.” A farm woman agreed: “The turnpike is finished and we can now go to town at all times and in all weather.” New turnpikes soon connected dozens of inland market centers to seaport cities.

Water transport was even quicker and cheaper, so state governments and private entrepreneurs dredged shallow rivers and constructed canals to bypass waterfalls and rapids. For their part, farmers in Kentucky and Tennessee and in southern Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois settled near the Ohio River and its many tributaries, so they could easily get goods to market. Similarly, speculators hoping to capitalize on the expansion of commerce bought up property in the cities along the banks of major rivers: Cincinnati, Louisville, Chattanooga, and St. Louis. Farmers and merchants built barges to carry cotton, grain, and meat downstream to New Orleans, which by 1815 was exporting about $5 million in agricultural products yearly.

TRACE CHANGE OVER TIME

Question

How did governments, banks, and merchants expand American commerce and manufacturing between 1780 and 1820?