Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 307

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 259

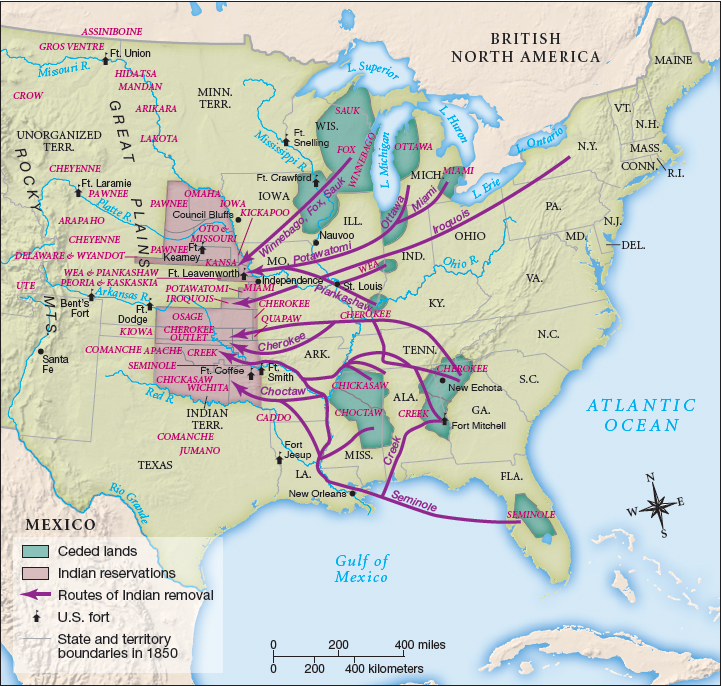

Continued Conflicts over Indian Lands

In 1830 Congress had passed the Indian Removal Act in hopes of settling the powerful Cherokee and Seminole tribes on land west of the Mississippi River. Not all Indian peoples went peacefully. As federal authorities forcibly removed the majority of Seminoles to Indian Territory between 1832 and 1835, a minority fought back. Jackson and his military commanders expected that this Second Seminole War would be short-lived. However, they misjudged the Seminoles’ strength; the power of their charismatic leader, Osceola; and the resistance of African American fugitives living among the Seminoles. Hundreds of southern slaves had fled to Florida in the early nineteenth century seeking freedom. Some married Seminole women, while others were reenslaved by Seminole Indians. But the Seminoles treated slaves with more leniency than did southern whites, allowing them to live on small farms with their own families and enjoy many of the rights of full members of the tribe. Thus free and enslaved blacks fought fiercely against Seminole removal.

The war continued long after Jackson left the presidency. During the seven-year guerrilla war, 1,600 U.S. troops died and the government spent more than $30 million. U.S. military forces defeated the Seminoles in 1842 only by luring Osceola into an army camp with false promises of a peace settlement. Instead, officers took him captive, finally breaking the back of the resistance. Still, to end the conflict, the U.S. government had to allow fugitive slaves living among the Seminoles to accompany the tribe to Indian Territory.

Members of the Cherokee nation also resisted removal, but they fought their battles in the arena of public opinion and in the courts. Throughout the early nineteenth century, growing numbers of Cherokees had embraced “Americanization” programs offered by white missionaries, educators, and government agents. John Ross and other Indian leaders urged Cherokee people to accommodate to white ways, believing it was the best means to ensure the continued control of their own communities. When Georgia officials sought to impose new regulations on the Cherokees living within the state’s borders, tribal leaders took them to court and sought to use evidence of their Christianity, domesticity, and republican government to maintain their rights.

In 1831 Cherokee Nation v. Georgia reached the Supreme Court, where Indian leaders demanded recognition as a separate nation as stipulated in the U.S. Constitution. Chief Justice John Marshall spoke for the majority when he ruled that all Indians in the United States were “domestic dependent nations” rather than fully sovereign governments. The Court thus denied a central part of the Cherokees’ claim. Yet the following year, in Worcester v. Georgia, Marshall and the Court declared that the state of Georgia could not impose state laws on the Cherokees, for they had “territorial boundaries, within which their authority is exclusive,” and that both their land and their rights were protected by the federal government.

President Jackson held a distinctly different view. He argued that only the removal of the Cherokees west of the Mississippi River could ensure their “physical comfort,” “political advancement,” and “moral improvement.” Most southern whites agreed because they sought to expand cotton production into fertile Cherokee fields. But Protestant women and men in the North launched a massive petition campaign in 1830 supporting the Cherokees’ right to their land. The Cherokees themselves forestalled action through Jackson’s second term, but many federal and state officials continued to press for the tribe’s removal.

Explore

Read a petition from Cherokee women resisting their removal in Document 10.4.

In December 1835, U.S. officials convinced a small group of Cherokee men—without tribal sanction—to sign the Treaty of New Echota. It proposed the exchange of 100 million acres of Cherokee land in the Southeast for $68 million and 32 million acres in Indian Territory. Cherokee leaders, including John Ross, lobbied Congress to reject the treaty, but to no avail. In May 1836, Congress approved the treaty by a single vote and set the date for final removal two years later. Although most of the 17,000 Cherokees resisted this plan, they had few means left to defy the U.S. government (Map 10.2).

In May 1838, the U.S. army began to forcibly remove any Cherokee who had not yet resettled in Indian Territory. General Winfield Scott, assisted by 7,000 U.S. soldiers, forced some 15,000 Cherokees into forts and military camps that June. The Cherokees spent the next several months without sufficient food, water, sanitation, or medicine. The situation went from bad to worse. In October, when the Cherokees began the march west, torrential rains were followed by snow. Although the U.S. army planned for a trip of less than three months, the journey actually took five months. As supplies ran short, many Indians, weakened by disease and hunger, died, including Ross’s wife. The remaining Cherokees completed this Trail of Tears, as it became known, in March 1839. But thousands remained near starvation a year later.