Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 499

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 412

The Growth of Corporations

With economic consolidation came the expansion of corporations. Before the age of large-scale enterprise, the predominant form of business ownership was the partnership. Unlike partnerships, corporations provided investors with “limited liability.” This meant that if the corporation went bankrupt, shareholders could not lose more than they had invested. Limited liability encouraged investment by keeping the shareholders’ investment in the corporation separate from their other assets. In addition, corporations provided “perpetual life.” Partnerships dissolved on the death of a partner, whereas corporations continued to function despite the death of any single owner. This form of ownership brought stability and order to financing, building, and perpetuating what was otherwise a highly volatile and complex business endeavor.

Capitalists devised new corporate structures to gain greater control over their industries. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company led the way by creating the trust, a monopoly formed through consolidation. To evade state laws against monopolies, Rockefeller created a petroleum trust. He combined other oil firms across the country with Standard Oil and placed their owners on a nine-member board of trustees that ran the company. Subsequently, Rockefeller fashioned another method of bringing rival businesses together. Through a holding company, he obtained stock in a number of other oil companies and held them under his control.

The movement to create trusts, Rockefeller boasted, “was the origin of the whole system of modern economic administration.” Statistics backed up his assessment. Between 1880 and 1905, more than three hundred mergers occurred in 80 percent of the nation’s manufacturing firms. Great wealth became heavily concentrated in the hands of a relatively small number of businessmen. Around two thousand businesses, a tiny fraction of the total number, dominated 40 percent of the nation’s economy.

Explore

See Document 16.1 for one cartoonist’s interpretation of Rockefeller’s power.

In their drive to consolidate economic power and shield themselves from risk, corporate titans generally had the courts on their side. In Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad Company (1886), the Supreme Court decided that under the Fourteenth Amendment, which originally dealt with the issue of federal protection of African Americans’ civil rights, a corporation was considered a “person.” In effect, this ruling gave corporations the same right of due process that the framers of the amendment had meant to give to former slaves. In the 1890s, a majority of the Supreme Court embraced this interpretation. The right of due process shielded corporations from prohibitive government regulation of the workplace, including the passage of legislation reducing the number of hours in the workday.

Yet trusts did not go unopposed. In 1890 Congress passed Senator Sherman’s Antitrust Act, which outlawed monopolies that prevented free competition in interstate commerce. The bill passed easily with bipartisan support because it merely codified legal principles that already existed. Sherman and his colleagues never intended to stifle large corporations, which through efficient business practices came to dominate the market. Rather, the lawmakers attempted to limit underhanded actions that destroyed competition. The judicial system further bailed out corporate leaders. In United States v. E.C. Knight Company (1895), a case against the “sugar trust,” the Supreme Court rendered the Sherman Act virtually toothless by ruling that manufacturing was a local activity within a state and that, even if it was a monopoly, it was not subject to congressional regulation. This ruling left most trusts in the manufacturing sector beyond the jurisdiction of the Sherman Antitrust Act.

The introduction of managerial specialists, already present in European firms, proved the most critical innovation for integrating industry. With many operations controlled under one roof, large-scale businesses required a corps of experts to oversee and coordinate the various steps of production. Comptrollers and accountants pored over financial records to keep track of every penny spent and dollar earned. Traffic managers directed the movement of raw materials into plants and finished products out for distribution. Marketing executives were in charge of advertising goods and finding new markets. Efficiency experts sought to cut labor costs and make the production process operate more smoothly. Frederick W. Taylor, a Philadelphia engineer and businessman, developed the principles of scientific management. Based on his concept of reducing manual labor to its simplest components and eliminating independent action on the part of workers, managers introduced time-and-motion studies. Using a stopwatch, they calculated how to break down a job into simple tasks that could be performed in the least amount of time. From this perspective, workers were no different from the machines they operated.

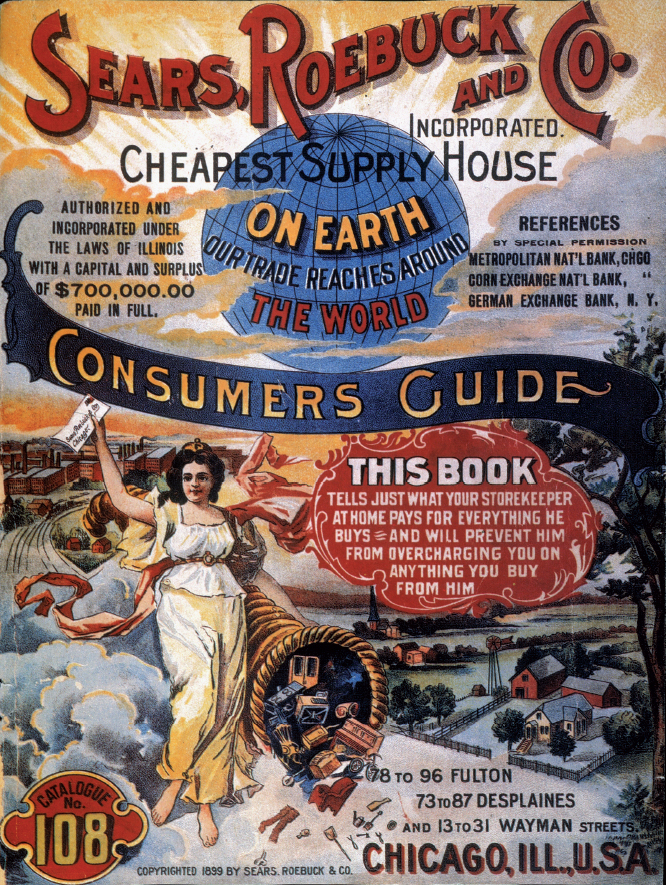

Another vital factor in creating large-scale industry was the establishment of retail outlets that could sell the enormous volume of goods pouring out of factories. As consumer goods became less expensive, retail outlets sprang up to serve the growing market for household items, including watches, jewelry, sewing machines, cameras, and an assortment of rugs and furniture. Customers could shop at department stores—such as Macy’s in New York City, Filene’s in Boston, Marshall Field’s in Chicago, Nordstrom’s in Seattle, Gump’s in San Francisco, Nieman Marcus in Dallas, Jacome’s in Tucson, Rich’s in Atlanta, and Burdine’s in Miami—where they were waited on by a growing army of salesclerks. Or they could buy the cheaper items in Frank W. Woolworth’s five and ten cent stores, which opened in towns and cities nationwide. Chain supermarkets—such as the Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company (A&P), founded in 1869—sold fruits and vegetables packed in tin cans. They also sold foods from the meatpacking firms of Gustavus Swift and Philip Armour, which shipped them on refrigerated railroad cars. Mail-order catalogs allowed Americans in all parts of the country to buy consumer goods without leaving their home. The catalogs of Montgomery Ward (established in 1872) and Sears, Roebuck (founded in 1886) offered tens of thousands of items. Rural free delivery (RFD), instituted by the U.S. Post Office in 1891, made it even easier for farmers and others living in the countryside to obtain these catalogs and buy their merchandise without having to travel miles to the nearest post office. By the end of the nineteenth century, the industrial economy had left its mark on almost all aspects of life in almost every corner of America.

Review & Relate

|

What were the key factors behind the acceleration of industrial development in late-nineteenth-century America? |

How did industrialization change the way American businessmen thought about their companies and the people who worked for them? |