Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 868

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 712

The Persistence of Liberalism

Despite the elections of Richard Nixon and the economic hard times that many encountered in the 1970s, political activism did not die out with the end of the militant 1960s. Many of the changes sought by liberals and radicals during the 1960s had entered the political and cultural mainstreams. Nor did the influence of the counterculture disappear. During the 1970s, long hairstyles and colorful clothes also entered the mainstream, and rock continued to dominate popular music. American youth and many of their elders experimented with recreational drugs, and the remaining sexual taboos of the 1960s fell. Many parents became resigned to seeing their daughters and sons living with boyfriends or girlfriends before getting married. And many of those same parents sought to expand their own sexual horizons by engaging in extramarital affairs or divorcing their spouses. The divorce rate increased 116 percent in the decade after 1965; in 1979 the rate peaked at 23 divorces per 1,000 married couples.

Rock music, long linked to sexual experimentation, continued to dominate the era. The popularity of disco music, glamorized by John Travolta in the blockbuster motion picture Saturday Night Fever (1977), emphasized dance beats over social messages, much like early rock ’n’ roll. However, listeners could still get deeper meaning and engaging melodies from the works of singer-songwriters, who crafted and recorded their own songs. The decade inspired artists such as Bruce Springsteen, Jackson Browne, and Billy Joel, whose performing energy and songs of loss, loneliness, urban decay, and adventure carried folk-rock music in new directions.

The antiwar movement and counterculture influenced popular culture in other ways. The film M*A*S*H (1970), though dealing with the Korean War, was a thinly veiled satire of the horrors of the Vietnam War, and in the late 1970s filmmakers began producing movies specifically about Vietnam and the toll the war took on ordinary Americans who served there. The television sitcom All in the Family gave American viewers the character of Archie Bunker, an opinionated blue-collar worker, in a comedy that dramatized the contemporary political and cultural war pitting conservatives against liberals. The show recounted the battle of the generations as Archie taunted his hippie-looking son-in-law with politically incorrect remarks about religious, racial, and ethnic minorities, feminists, and liberals.

The battles fought in the fictional Bunker household played out in real life. In the 1970s, the women’s movement gained strength, but it also attracted powerful opponents. The 1973 Supreme Court victory for abortion rights in Roe v. Wade (see chapter 26) mobilized women on all sides of the issue. Pro-choice advocates pointed out that previous laws criminalizing abortion exposed pregnant women who sought the procedure to unsanitary and dangerous methods of ending pregnancies. However, Roe v. Wade produced an equally strong reaction from abortion opponents. Pro-life advocates believed that a fetus was a human being and must be granted full protection from what they considered to be murder. In 1976 Congress responded to abortion opponents by passing legislation prohibiting the use of federal funds for impoverished women seeking to terminate their pregnancies.

Feminists engaged in other debates in this decade, often clashing with more conservative women. The National Organization for Women (NOW) and its allies succeeded in getting thirty-five states out of a necessary thirty-eight to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), which prevented the abridgment of “equality of rights under law . . . by the United States or any State on the basis of sex.” In response, other women activists formed their own movement to block ratification. Phyllis Schlafly, a conservative activist, founded the Stop ERA organization. She argued that the ERA would create a “unisex society” and deprive “women of the rights they already have, such as the right of a wife to be supported by her husband,” attend a single-sex college, use women’s-only bathrooms, and avoid military combat. Despite the inroads made by feminists, traditional notions of femininity appealed to many women and to male-dominated legislatures. The remaining states refused to ratify the ERA, thus killing the amendment in 1982, when the ratification period expired.

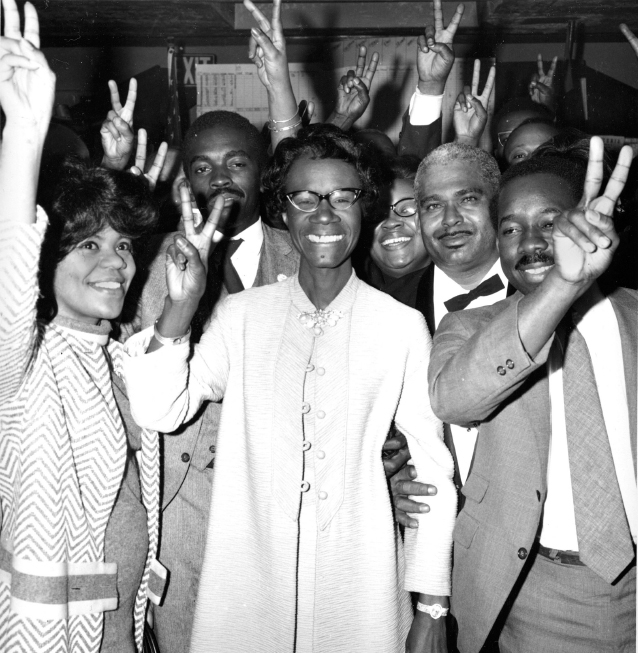

Despite the failure to obtain ratification of the ERA, feminists achieved significant victories. In 1972 Congress passed the Educational Amendments Act. Title IX of this law prohibited colleges and universities that received federal funds from discriminating on the basis of sex, leading to substantial advances in women’s athletics. Many more women sought relief against job discrimination through the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, resulting in major victories against such firms as the American Telephone and Telegraph Company. NOW membership continued to grow, and the number of battered women’s shelters and rape crisis centers multiplied in towns and cities across the country. Women saw their ranks increase on college campuses, in both undergraduate and professional schools. Women also began entering politics in large enough numbers, especially at the local and state levels, to justify the formation of the National Women’s Political Caucus in 1971. At the national level, women such as Shirley Chisholm and Geraldine Ferraro of New York, Barbara Jordan of Texas, and Patricia Schroeder of Colorado won seats in Congress. Women’s political associations—such as Emily’s List, founded in 1984, and the Fund for a Feminist Majority, founded in 1987—saw their memberships and donations soar, especially after Anita Hill testified against the nomination of Clarence Thomas to the Supreme Court.

At the same time, women of color sought to broaden the definition of feminism to include struggles against race and class oppression as well as sex discrimination. In 1974 a group of black feminists, led by author Barbara Smith, organized the Combahee River Collective and proclaimed: “We . . . often find it difficult to separate race from class from sex oppression because in our lives they are most often experienced simultaneously.” Chicana and other Latina feminists drew strength from African American women in extending women’s liberation beyond the confines of the white middle class. In 1987 feminist poet and writer Gloria Anzaldúa wrote: “Though I’ll defend my race and culture when they are attacked by non-mexicanos . . . I abhor some of my culture’s ways, how it cripples its women . . . our strengths used against us, lowly [women] bearing humility with dignity.”

Explore

See Document 27.1 for an excerpt from the Combahee River Collective.

Another outgrowth of 1960s liberal activism that flourished in the 1970s was the effort to clean up and preserve the environment. The publication of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring in 1962 had renewed awareness of what Progressive Era reformers called conservation (see chapter 19). Carson expanded the concept of conservation to include ecology, which addressed the relationships of human beings and other organisms to their environments. By exploring these connections, she offered a revealing look at the devastating effects of powerful pesticides, especially DDT, on birds and fish, as well as on the human food chain and water supply.

This new environmental movement not only focused on open spaces and national parks but also sought to publicize urban environmental problems. By 1970, 53 percent of Americans considered air and water pollution to be one of the top issues facing the country, up from only 17 percent five years earlier. Responding to this shift in public opinion, in 1971 President Nixon established the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and signed the Clean Air Act, which regulated auto emissions. Two years later, Congress banned the sale of DDT.

Not everyone embraced environmentalism. As the EPA toughened emission standards, automobile manufacturers complained that the regulations forced them to raise prices and hurt an industry that was already feeling the threat of foreign competition, especially from Japan. Workers were also affected, as declining sales forced companies to lay off employees. Similarly, passage of the Endangered Species Act of 1973 pitted timber companies in the Northwest against environmentalists. The new law prevented the federal government from funding any projects that threatened the habitat of animals at risk of extinction.

Several disasters heightened public demands for stronger government oversight of the environment. In 1978 women living near Love Canal outside of Niagara Falls, New York, complained about unusually high rates of illnesses and birth defects in their community. Investigations revealed that their housing development had been constructed on top of a toxic waste dump. This discovery spawned grassroots efforts to clean up this area as well as other contaminated communities. In 1980 Congress responded by passing the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (known as Superfund) to clean up sites contaminated with hazardous substances. Further inquiries showed that the presence of such poisonous waste dumps disproportionately affected minorities and the poor. Critics called the placement of these waste locations near African American and other minority communities “environmental racism” and launched a movement for environmental justice.

The most dangerous threat came in March 1979 at the Three Mile Island nuclear plant near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. A broken valve at the plant leaked coolant and threatened the meltdown of the reactor’s nuclear core. As officials quickly evacuated residents from the surrounding area, employees at the plant narrowly averted catastrophe by fixing the problem before an explosion occurred. Grassroots activists, such as the Clamshell Alliance in New Hampshire, protested and raised public awareness against the construction of additional power facilities. They also convinced existing utility companies to slow down their plans for expanding the output of nuclear power.