Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 230

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 194

Literary and Cultural Developments

While frontier colleges expanded educational and cultural opportunities, older universities also contributed to the development of a national identity. A group known as the Hartford Wits, most of them graduates of Yale, gave birth to a new literary tradition. This circle of poets, playwrights, and essayists expressed distinctly American (though largely Federalist) perspectives. Members of the Hartford Wits published paeans to democracy, satires about Shays’s Rebellion, and plays about specifically American dilemmas, such as the proper role of the central government in a republican nation.

The young nation also produced a number of novelists. Advances in printing and the production of paper increased the circulation of novels, a literary genre developed in Britain and continental Europe at the turn of the eighteenth century. At the same time, improvements in girls’ education produced a growing audience among women, who were thought to be the genre’s most avid readers. Novelists like Susanna Rowson and Charles Brockden Brown sought to educate readers about virtuous action by placing ordinary women and men in moments of high drama that tested their moral character. They also emphasized new marital ideals, by which husbands and wives became partners and companions in building a home and family.

Explore

See Document 8.1 for a dramatic warning to young women from novelist Susanna Rowson.

Among the most important American literary figures to emerge in the early nineteenth century was Washington Irving. While living in Europe in the 1810s, he wrote a series of short stories and essays, including “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” and “Rip Van Winkle,” that were published in his Sketchbook in 1820. These popular folktales drew on the Dutch culture of the Hudson valley region in New York and often poked fun at more celebratory tales of early American history. But Irving also wrote serious essays. One challenged colonial accounts of Indian-English conflicts, which he argued ignored courageous actions by Indians while applauding atrocities committed by whites.

While Irving achieved fame by making fun of romanticized versions of American history, books that glorified the nation’s past were also enormously popular. Among the most influential were a three-volume History of the Revolution (1805) written by Mercy Otis Warren and the Life of Washington (1806), a celebratory if somewhat fanciful biography by an Anglican clergyman, Mason “Parson” Weems. The influence of American authors increased as residents in both urban and rural areas purchased growing numbers of books. By 1820–1821, for instance, an astonishing 80 percent of households of middling wealth in Chester County, Pennsylvania, owned books. See e-Document Project 8: Literary and Cultural Developments in the Early United States.

Artists, too, devoted considerable attention to historical themes. Charles Willson Peale painted Revolutionary generals while serving in the Continental Army and became best known for his portraits of George Washington. Samuel Jennings offered a more radical perspective on the nation’s character when he presented Liberty Displaying the Arts and Sciences (1792) to the Philadelphia Library Company. Many of the library’s directors opposed slavery, and Jennings portrayed Lady Liberty offering a book to a group of attentive African Americans. Engravings, which were less expensive than paintings, circulated widely, and many also highlighted national symbols like flags, eagles, and Lady Liberty.

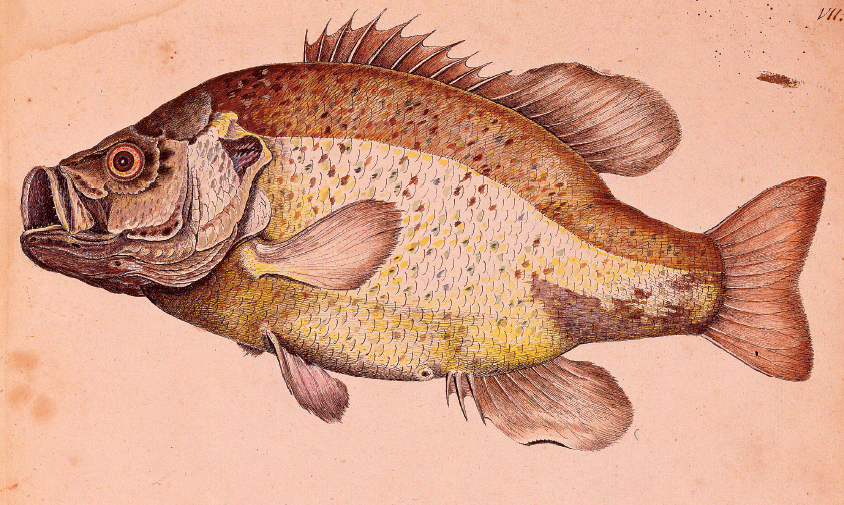

Engravings of nature were especially popular. Books like Cleaveland’s Elementary Treatise on Mineralogy and Geology included plates that illustrated rocks and geological formations. William Bartram’s Travels (1791), based on his journey through the southeastern United States and Florida, illustrated plants and animals, such as the alligator, previously unknown to Anglo-American scientists.

In the 1780s, Benjamin Franklin helped found the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia to promote American literature and science. Like-minded gentlemen in Boston and Salem established the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Colleges like Bowdoin, Franklin, and Dickinson advanced scientific research in frontier regions, while the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia established the nation’s first medical school. As in the arts, American scientists built on developments in continental Europe and Great Britain, but the young nation prided itself on contributing its own expertise.