Opening the Door in China

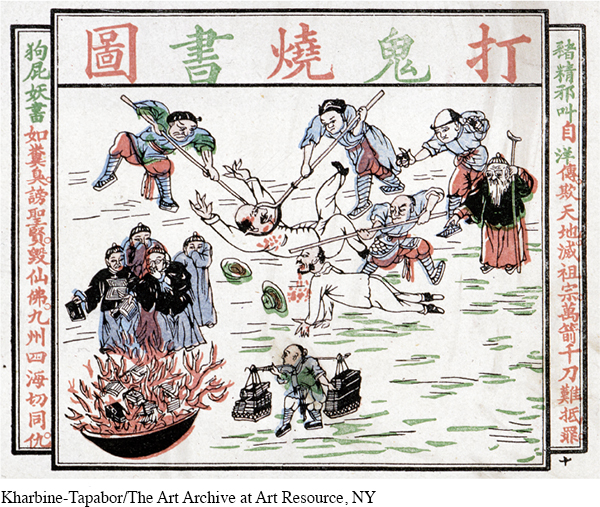

Roosevelt displayed U.S. power in other parts of the world. His major concern was protecting the Open Door policy in China that his predecessor McKinley had engineered to secure naval access to the Chinese market. By 1900 European powers had already dominated foreign access to Chinese markets, leaving scant room for newcomers. When the United States sent 2,500 troops to China in August 1900 to help quell a nationalist rebellion against foreign involvement known as the Boxer uprising, European competitors in return were compelled to allow the United States free trade access to China.

In 1904 the Russian invasion of the northern Chinese province of Manchuria prompted the Japanese to attack the Russian fleet. Roosevelt admired Japanese military prowess, but he worried that if Japan succeeded in driving the Russians out of the area, it would cause “a real shifting of equilibrium as far as the white races are concerned.” To prevent that from happening, Roosevelt convened a peace conference in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, in 1905. Under the agreement reached at the conference, Japan received control over Korea and parts of Manchuria but pledged to support the United States’ Open Door policy. In 1906 the president sent sixteen U.S. battleships on a trip around the globe in a show of force meant to demonstrate that the United States was serious about taking its place as a premier world power.

When Roosevelt’s secretary of war, William Howard Taft, became president (1909–1913), he continued his predecessor’s foreign policy with slight modification. Proclaiming that he would rather substitute “dollars for bullets,” Taft encouraged private bankers to invest money in the Caribbean and Central America, a policy known as dollar diplomacy. Yet Taft did not rely on financial influence alone. He dispatched more than 2,000 U.S. troops to the region to guarantee economic stability.

Taft’s diplomacy also led to extensive intervention in Nicaragua. In 1909 U.S. fruit and mining companies in Nicaragua helped install a regime sympathetic to their interests. When a group of rebels threatened this pro-U.S. government, Taft invoked the Roosevelt Corollary and sent in U.S. marines to police the country and deter further uprisings. They remained there for another twenty-five years. Under this occupation, U.S. bankers took control of Nicaragua’s customs houses and paid off debts owed to foreign investors, a move meant to forestall outside intervention in a nation that was now under U.S. “protection.”

REVIEW & RELATE

How did the United States assert its influence and control over Latin America in the early twentieth century?

How did U.S. policies in Latin America mirror U.S. policies in Asia?

Exploring American HistoriesPrinted Page 662

Exploring American Histories Value EditionPrinted Page 490

Chapter Timeline