The Harlem Renaissance

The greatest challenge to conventional notions about race came from African Americans. The influx of southern black migrants to the North during and after World War I created a black cultural renaissance, with New York City’s Harlem and the South Side of Chicago leading the way. Gathered in Harlem—with a population of more than 120,000 African Americans in 1920 and growing every day—a group of black writers paid homage to the New Negro, the second generation born after emancipation. These New Negro intellectuals refused to accept white supremacy. They expressed pride in their race, sought to perpetuate black racial identity, and demanded full citizenship and participation in American society. Black writers and poets drew on themes from African American life and history for inspiration in their literary works.

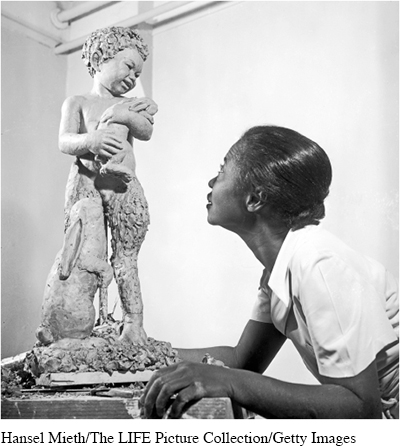

The poets, novelists, and artists of the Harlem Renaissance captured the imagination of blacks and whites alike. Many of these artists increasingly rejected white standards of taste as well as staid middle-class black values. Writers Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston in particular drew inspiration from the vernacular of African American folk life. In 1926 Hughes defiantly asserted: “We younger Negro artists who create now intend to express our dark-skinned selves without fear or shame. If white people are pleased, we are glad. If they are not, it doesn’t matter.” See Document Project 21: The New Negro and the Harlem Renaissance.

Black music became a vibrant part of mainstream American popular culture in the 1920s. Musicians such as Ferdinand “Jelly Roll” Morton, Louis Armstrong, Edward “Duke” Ellington, and singer Bessie Smith developed and popularized two of America’s most original forms of music—jazz and the blues. These unique compositions grew out of the everyday experiences of black life and expressed the thumping rhythms of work, pleasure, and pain. Such music did not remain confined to dance halls and clubs in black communities; it soon spread to white musicians and audiences for whom the hot beat of jazz rhythms meant emotional freedom and the expression of sexuality.

Exploring American HistoriesPrinted Page 699

Exploring American Histories Value EditionPrinted Page 517

Chapter Timeline