Baby Boom

Explore

See Document 25.1 for Adlai Stevenson’s speech at Smith explaining why a woman’s place is in the home.

During the postwar years, with traditional gender roles largely reinstated and the economy booming, nuclear families began to grow. In 1955 Illinois governor Adlai Stevenson told the women graduates at Smith College that they could do their part to maintain a free society as wives and mothers. Educated women had an important role to play in maintaining a household that boosted their husband’s morale. The mothers of these female college graduates had suffered through the Great Depression, when keeping the birthrate low was one way to assist the family. That was about to change.

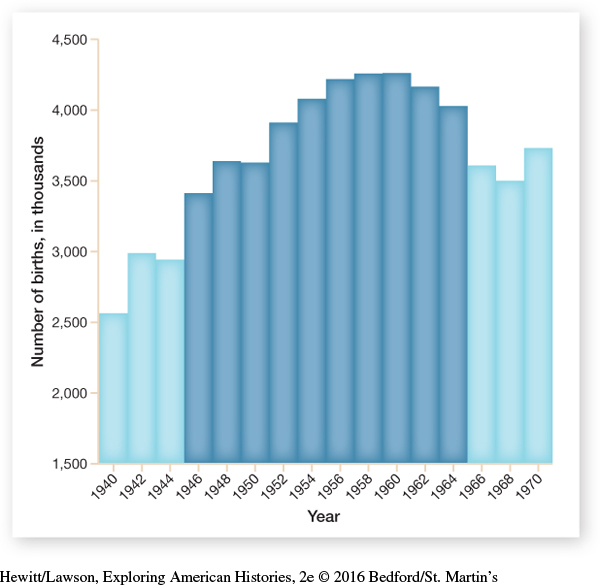

In the 1940s and 1950s the average age at marriage was younger than it had been in the 1930s. On average, men married for the first time at the age of just under twenty-three, and 49 percent of women married by nineteen. Couples also produced children at an astonishing rate. In the 1950s, the growth rate in the U.S. population approached that of India (Figure 25.2).

Marriage and parenthood reflected a culture spurred by the Cold War. Public officials and the media urged young men and women to build nuclear families in which the father held a paying job and the mother stayed at home and raised her growing family. Doing so would strengthen the moral fiber of the United States in its battle against Soviet communism.

Parents could also look forward to their children surviving diseases that had resulted in many childhood deaths in the past. In the 1950s, children received vaccinations against diphtheria, whooping cough, and tuberculosis before they entered school. The most serious illness affecting young children remained the crippling disease of polio, or infantile paralysis. In 1955 Dr. Jonas Salk developed a successful injectable vaccine against the disease. On April 12, 1955, news bulletins interrupted scheduled television programs to announce Salk’s breakthrough, and, as one writer recalled, “citizens rushed to ring church bells and fire sirens, shouted, clapped, sang, and made every kind of joyous noise they could.” By the mid-1960s polio was no longer a public health menace in the United States.

Exploring American HistoriesPrinted Page 829

Exploring American Histories Value EditionPrinted Page 611

Chapter Timeline