4.6 Hypnosis

KEY THEME

During hypnosis, people respond to suggestions with changes in perception, memory, and behavior.

KEY QUESTIONS

What characteristics are associated with responsiveness to hypnotic suggestions?

What are some important effects of hypnosis?

How has hypnosis been explained?

What is hypnosis? Hypnosis can be defined as a cooperative social interaction in which the hypnotic participant responds to suggestions made by the hypnotist. These suggestions for imaginative experiences can produce changes in perception, memory, thoughts, and behavior (American Psychological Association, 2005a).

hypnosis

(hip-NO-sis) A cooperative social interaction in which the hypnotized person responds to the hypnotist’s suggestions with changes in perception, memory, and behavior.

For many people the word hypnosis conjures up the classic but sinister image of a hypnotist slowly swinging a pocket watch back and forth. But, as psychologist John Kihlstrom (2001) explains, “The hypnotist does not hypnotize the individual. Rather, the hypnotist serves as a sort of coach or tutor whose job is to help the person become hypnotized.”

The word hypnosis is derived from the Greek hypnos, meaning “sleep.” However, rather than being a sleeplike trance, hypnosis produces a highly focused, absorbed state of attention that minimizes competing thoughts and attention (Oakley & Halligan, 2013). It is also characterized by increased responsiveness to suggestions, vivid images and fantasies, and a willingness to accept distortions of logic or reality. During hypnosis, people temporarily suspend their sense of initiative and voluntarily accept and follow the hypnotist’s instructions (Hilgard, 1986a). However, they typically remain aware of who they are, where they are, and the events that are transpiring.

People vary in their responsiveness to hypnotic suggestions (see Nash, 2008). About 15 percent of adults are highly susceptible to hypnosis, and 10 percent are difficult or impossible to hypnotize. Children tend to be more responsive to hypnosis than are adults (Rhue, 2010).

The best candidates for hypnosis are individuals who approach the experience with positive, receptive attitudes. The expectation that you will be responsive to hypnosis also plays an important role (Silva & others, 2005). People who are highly susceptible to hypnosis have the ability to become deeply absorbed in fantasy and imaginary experience. For instance, they easily become absorbed in reading fiction, watching movies, and listening to music (Kihlstrom, 2007; Milling & others, 2010).

Effects of Hypnosis

Deeply hypnotized subjects sometimes experience profound changes in their subjective experience of consciousness. They may report feelings of detachment from their bodies, profound relaxation, or sensations of timelessness. Often, they will later report that carrying out the hypnotist’s suggestions seemed to happen by itself, as if the action occurred without effort or conscious control (Polito & others, 2014).

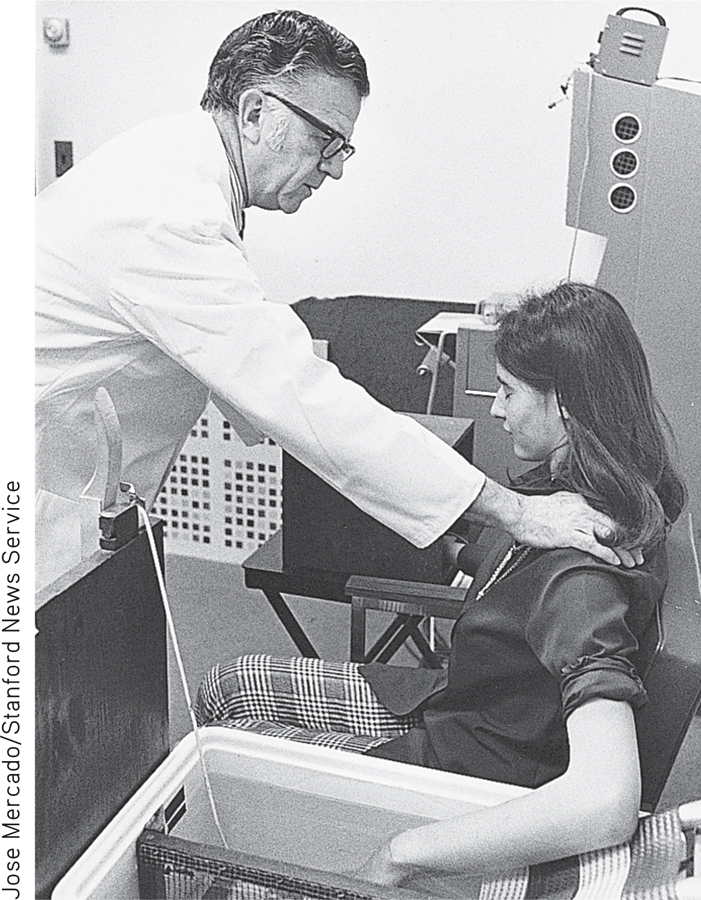

Sensory changes that can be induced through hypnosis include hallucinations, temporary blindness, deafness, or a complete loss of sensation in some part of the body (Kihlstrom, 2007). For example, when the suggestion is made to a highly responsive subject that her arm is numb and cannot feel pain, she will not consciously experience the pain of a pinprick or of having her arm immersed in ice water. This property of hypnosis has led to its use as a technique in pain control (Adachi & others, 2014; Jensen & Patterson, 2014). Painful dental and medical procedures, including surgery, have been successfully performed with hypnosis as the only anesthesia (Hilgard & others, 1994; Salazar & others, 2010).

Hypnosis can also influence behavior outside the hypnotic state. When a posthypnotic suggestion is given, the person will carry out that specific suggestion after the hypnotic session is over. For example, under hypnosis, a student was given the posthypnotic suggestion that the number 5 no longer existed. He was brought out of hypnosis and then asked to count his fingers. He counted 11 fingers! Counting again, the baffled young man was at a loss to explain his results.

posthypnotic suggestion

A suggestion made during hypnosis asking a person to carry out a specific instruction following the hypnotic session.

Some posthypnotic suggestions have been reported to last for months, but most last only a few hours or days. So, even if the hypnotist does not include some posthypnotic signal to cancel the posthypnotic suggestion, the suggestion will eventually wear off.

Memory can be significantly affected by hypnosis (see Kihlstrom, 2007). Posthypnotic amnesia is produced by a hypnotic suggestion that suppresses the memory of specific information, such as the subject’s name, address, or phone number. The effects of posthypnotic amnesia are usually temporary, disappearing either spontaneously or when a posthypnotic signal is suggested by the hypnotist. When the signal is given, the information floods back into the subject’s mind.

posthypnotic amnesia

The inability to recall specific information because of a hypnotic suggestion.

Can hypnosis enhance memory, allow you to “zoom in” on details of a crime that have been forgotten, or recover long-forgotten memories? No. Compared with regular police interview methods, hypnosis does not significantly enhance memory or improve the accuracy of memories (Mazzoni & others, 2010). In contrast, efforts to enhance memories with hypnosis can produce distorted and inaccurate recollections. In fact, one effect of hypnosis is to greatly increase confidence in incorrect memories. False memories, also called pseudomemories, can be inadvertently created when hypnosis is used to aid recall, a topic discussed in greater detail in Chapter 6, on memory (Lynn & others, 2003; Mazzoni & Scoboria, 2007).

CRITICAL THINKING

How to Think Like a Scientist

Are the changes in perception, thinking, and behaviors that occur during hypnosis the result of a “special” or “altered” state of consciousness? Here, we’ll consider the evidence for three competing points of view on this issue.

The State View: Hypnosis Involves a Special State

The “state” explanation contends that hypnosis is a unique state of consciousness, distinctly different from normal waking consciousness (Wagstaff, 2014). The state view is perhaps best represented by Hilgard’s neodissociation theory of hypnosis. According to this view, consciousness is split into two simultaneous streams of mental activity during hypnosis. One stream of mental activity remains conscious, but a second stream of mental activity—the one responding to the hypnotist’s suggestions—is “dissociated” from awareness (Sadler & Woody, 2010). So according to the neodissociation theory, the hypnotized young woman shown on page 157 reported no pain because the painful sensations were dissociated from awareness.

The Non-State View: Ordinary Psychological Processes

Some psychologists reject the notion that hypnotically induced changes involve a “special” state of consciousness. According to the social-cognitive view of hypnosis, subjects are responding to the social demands of the hypnosis situation. They act the way they think good hypnotic subjects are supposed to act, conforming to the expectations of the hypnotist, their own expectations, and situational cues (Lynn & Green, 2011). In this view, the “hypnotized” young woman on page 157 reported no pain because that’s what she expected to happen during the hypnosis session.

To back up the social cognitive theory of hypnosis, Nicholas Spanos (1991, 1994, 2005) and his colleagues amassed an impressive array of evidence showing that highly motivated people often perform just as well as hypnotized subjects in demonstrating pain reduction, amnesia, age regression, and hallucinations. Studies of people who simply pretended to be hypnotized have shown similar results. On the basis of such findings, non-state theorists contend that hypnosis can be explained in terms of rather ordinary psychological processes, including imagination, situational expectations, role enactment, compliance, and conformity (Wagstaff & Cole, 2005).

The Imaginative Suggestibility View

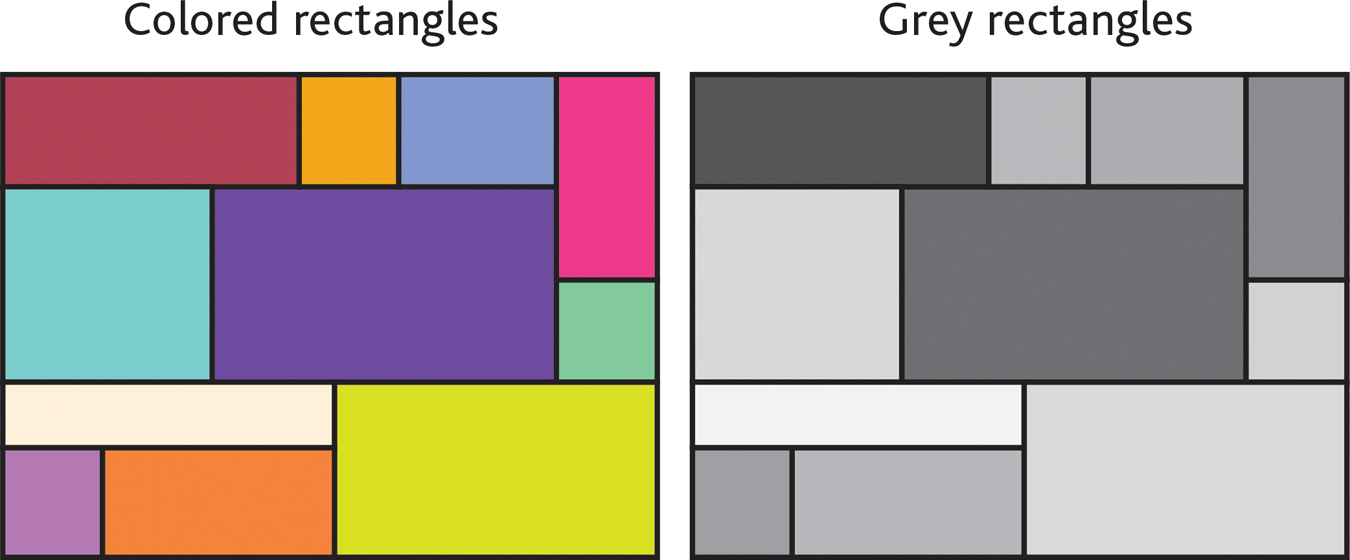

Challenging the social cognitive view, however, are the results of numerous brain-imaging studies showing that hypnosis can produce alterations in brain function (see Oakley & Halligan, 2013). For example, in one study, hypnotized participants were given instructions to “drain” color from a visual image made up of colored rectangles or, conversely, to “add” color” to a visual image made up of gray rectangles, like those shown to the right. The brain function of hypnotized participants reflected the hypnosis-induced visual hallucination—not the actual images that participants viewed (Kosslyn & others, 2000).

Psychologists Irving Kirsch and Wayne Braffman (2001) dismiss the social cognitive view that hypnotic subjects are merely acting. But they also contend that brain-imaging studies don’t necessarily prove that hypnosis is a unique state. Rather, Kirsch and Braffman maintain that such studies emphasize individual differences in imaginative suggestibility—the degree to which a person is able to experience an imaginary state of affairs as if it were real (Kirsch, 2014; Kirsch & others, 2011).

Braffman and Kirsch (1999) have shown that many highly suggestible participants were just as responsive to suggestions when they had not been hypnotized as when they had been hypnotized. “Hypnotic responses reveal an astounding capacity that some people have to alter their experience in profound ways,” Kirsch and Braffman (2001) write. “Hypnosis is only one of the ways in which this capacity is revealed. It can also be evoked—and almost to the same extent—without inducing hypnosis.”

Supporting this approach is a new study that duplicated the brain-imaging research described above with one important difference: All of the participants were given the suggestions to alter their color perception of the image of rectangles, but only half of them were formally hypnotized (McGeown & others, 2012). Half of the participants scored high in hypnotic suggestibility, and half scored low in suggestibility. The results showed that whether or not they were hypnotized, highly suggestible participants were able to “see” the visual hallucinations, and low-suggestible participants were not. Hypnosis slightly increased the vividness of the subjective perception of the hallucination in the highly suggestible participants, but it had no effect at all on the low-suggestible participants.

Despite the controversy over how best to explain hypnotic effects, psychologists do agree that hypnosis can be a highly effective therapeutic technique (Lynn & others, 2010). And, increasingly, cognitive neuroscientists are using hypnosis as a tool to manipulate subjective awareness (Oakley & Halligan, 2013).

CRITICAL THINKING QUESTIONS

Does the fact that highly motivated subjects can “fake” hypnotic effects invalidate the notion of hypnosis as a unique state of consciousness? Why or why not?

What kinds of evidence could prove or disprove the notion that hypnosis is a unique state of consciousness?

Explaining Hypnosis

CONSCIOUSNESS DIVIDED?

How can hypnosis be explained? Psychologist Ernest R. Hilgard (1986a, 1991, 1992) believed that the hypnotized person experiences dissociation—the splitting of consciousness into two or more simultaneous streams of mental activity. According to Hilgard’s neodissociation theory of hypnosis, a hypnotized person consciously experiences one stream of mental activity that complies with the hypnotist’s suggestions. But a second, dissociated stream of mental activity is also operating, processing information that is unavailable to the consciousness of the hypnotized subject. Hilgard (1986a, 1992) referred to this second, dissociated stream of mental activity as the hidden observer. (The phrase hidden observer does not mean that the hypnotized person has multiple personalities.)

dissociation

The splitting of consciousness into two or more simultaneous streams of mental activity.

neodissociation theory of hypnosis

Theory proposed by Ernest Hilgard that explains hypnotic effects as being due to the splitting of consciousness into two simultaneous streams of mental activity, only one of which the hypnotic participant is consciously aware of during hypnosis.

hidden observer

Hilgard’s term for the hidden, or dissociated, stream of mental activity that continues during hypnosis.

Some theorists do not agree that hypnotic phenomena are due to dissociation, divided consciousness, or a hidden observer. Alternative theories include the social cognitive and imaginative suggestibility theories. We discuss this controversy in the Critical Thinking box, “Is Hypnosis a Special State of Consciousness?”

LIMITS AND APPLICATIONS OF HYPNOSIS

MYTH  SCIENCE

SCIENCE

Is it true that you can be hypnotized against your will?

Although the effects of hypnosis can be dramatic, there are limits to the behaviors that can be influenced by hypnosis. First, contrary to popular belief, you cannot be hypnotized against your will. Second, hypnosis cannot make you perform behaviors that are contrary to your morals and values. Thus, you’re very unlikely to commit criminal or immoral acts under the influence of hypnosis—unless, of course, you find such actions acceptable (Hilgard, 1986b).

Third, hypnosis cannot make you stronger than your physical capabilities or bestow new talents. However, hypnosis can enhance physical skills or athletic ability by increasing self-confidence and concentration (Barker & Jones, 2006; Morgan, 2002). TABLE 4.2 provides additional examples of how hypnosis can be used to help people.

Help Through Hypnosis

| Research has demonstrated that hypnosis can effectively: Reduce pain and discomfort associated with cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, burn wounds, and other chronic conditions Reduce pain and discomfort associated with childbirth Reduce the use of narcotics to relieve postoperative pain Improve the concentration, motivation, and performance of athletes Lessen the severity and frequency of asthma attacks Eliminate recurring nightmares Enhance the effectiveness of psychotherapy in the treatment of obesity, hypertension, and anxiety Remove warts Eliminate or reduce stuttering Suppress the gag reflex during dental procedures |

| Sources: Research from Dubreuil & Spanos (1993); Covino & Pinnell (2010); Ginandes (2006); Lynn & others (2006); Nash & others (2009); Stegner & Morgan (2010). |

Can hypnosis be used to help you lose weight, stop smoking, or stop biting your nails? Hypnosis is not a magic bullet. However, research has shown that hypnosis can be helpful in modifying problematic behaviors, especially when used as part of a structured treatment program (Lynn & others, 2010). For example, when combined with cognitive-behavioral therapy or other supportive treatments, hypnosis has been shown to help motivated people quit smoking (Elkins & others, 2006; Green & others, 2006; Lynn & Kirsch, 2006). In children and adolescents, hypnosis can be an effective treatment for such habits as thumb-sucking, nail-biting, and compulsive hair-pulling (Rhue, 2010).