Chapter Introduction

MYTH OR SCIENCE?

Is it true …

That the genes you inherit provide an unchanging “blueprint” that determines your physical characteristics, abilities, and personality traits?

Purestock/age fotostock

Purestock/age fotostockThat talking “baby talk” to infants and toddlers won’t harm their language development?

That educational videos, like Baby Einstein, help babies learn how to talk?

That most adolescents have poor relationships with their parents?

That many middle-aged people experience a “midlife crisis”?

That marital happiness declines when children leave the home, somethingthing called the “empty nest syndrome”?

That dying people go through five predictable stages—denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance?

9

Lifespan Development

AVTG/Getty Images

Future Plans

PROLOGUE

IN THIS CHAPTER:

YOUR AUTHORS SANDY AND DON HAVE MOVED several times since we began the first edition of this textbook. Moving never seems to go smoothly. Despite the best of intentions, the night before the moving van shows up is always a chaotic, frenzied scene. Jumbled piles of random objects get frantically tossed into boxes. “This can all get sorted out later,” we reason. This rationalization works well until “later” actually arrives and we’re confronted by the sea of boxes marked “basement,” “files,” and “miscellaneous.”

Moving is one of those events that forces you to reflect on your past. Memories are unearthed from the corners of drawers, pantry shelves, and storage cabinets. Don’s skydiving and pilot manuals, found at the bottom of a dilapidated cardboard box. Sandy’s rock tumbler. Laura’s preschool artwork.

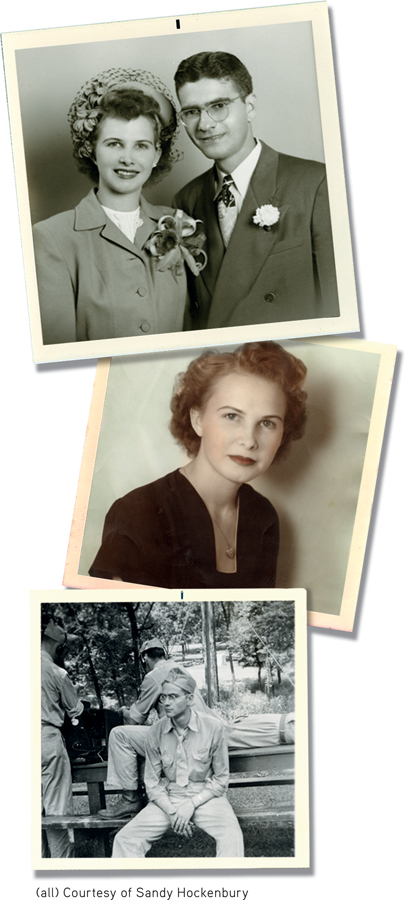

And episodes from the lives of others, too. From one dusty box, Laura gently pulled a carefully wrapped, framed picture. It was a hand-colored portrait photo of a beautiful young woman with delicate features and a sweet, tentative smile.

“That’s Grandma Fern, when she was about your age,” Sandy said. “Wasn’t she pretty?” Sandy reached into the box, uncovering another treasure, “Look, here’s Grandpa Erv and Grandma Fern’s wedding photo.”

“How come Grandma isn’t wearing a wedding dress?” Laura asked.

“Well, they got married right after World War II. It was the style then to wear a tailored suit. Nobody had extra money, and there were all kinds of shortages. Just think—Fernie was only 19 years old, not much older than you are now!”

“What’s this old thing?” Laura asked, holding up a crumbling cardboard mailing tube with a half-cent postage stamp still on it. Sandy pulled an engraved certificate out of the tube and carefully unrolled it. She read, “This certifies that Erwin Schmidt has been awarded membership in the ’49ers, an organization of young businessmen chosen from among the boy salesmen of Liberty Weekly. He has been selected because of his exceptional sales achievements, outstanding character, splendid personality, and unquestioned loyalty to his duties.” Shaking her head in amazement, Sandy said, “It’s dated October 10, 1930. Erv would have been only 11 years old. I can’t believe he saved this for all those years.”

All of us are shaped by the communities in which we grow up. In Fern’s case, that community was a tiny farming town in the 1930s. In contrast to Fern’s childhood spent caring for her younger siblings in rural Wisconsin, Erv was an only child in the thriving German community of Chicago’s Lincoln Square in the 1920s. Fern’s stories of chasing chickens to catch and kill for Sunday dinner were hard for her children and grandchildren to believe. But so were Erv’s stories of roller-skating down Chicago streets and sleeping on fire escapes and Lake Michigan beaches on hot summer nights in the city.

We’re also profoundly influenced by historical events. Just as the Great Depression defined Fern’s and Erv’s childhoods, World War II defined their young adult years. Among the treasures we discovered were shoe boxes filled with curling black-and-white snapshots that Erv took of his buddies at the Army Air Force training camp right before he “shipped out” for the Philippines and New Guinea.

“Mom, what is this thing?” Laura asked, pulling a dangerous-looking tool from a dusty canvas U.S. Army surplus bag.

“That’s my rock pick,” Sandy replied. “Be careful with that—it’s pretty sharp. Just think, I used to be able to take that onboard with me when I flew out west to go rock collecting.”

“Seriously?” Laura said in disbelief. Of course, Laura doesn’t remember a time when people got on planes without having their carry-on luggage searched for potential weapons. Metal detectors and concrete barriers in front of government buildings are an accepted part of her daily life just as bread lines and victory gardens were for her grandparents.

Laura had her own boxes of memories: Legos, Beanie Babies, and Barbies. Another box held college catalogs, SAT practice tests, programs from high school events, and pictures of friends. And then there were the stacks of T-shirts, commemorating everything from state soccer championships to volunteering at the Oklahoma Firefighters’ Burn Camp.

“You really need to sort through all that stuff and decide what you want to keep,” Sandy said.

Why did Erv keep his faded award certificate? Or his gymnastics medals, high school report cards, and an eighth-grade autograph book that Sandy found carefully preserved in an old cigar box? Why did Don keep all of his pilot logs, his skydiving manuals, and his father’s cuff links? For that matter, why did Sandy still have her rock pick?

It’s a task that each of us faces. Sorting out our past, framing our future. Who have we been? Who shall we become? What will our life story be?